Even though most of the laws governing land management in Jammu and Kashmir witnessed rudimentary shifts in the last few years, the land resource continues to be a touchy subject. A housing scheme for the poor remained in the news for many days owing to land. Masood Hussain details the evolution of the land redistribution process in Kashmir’s recent past

After the government unlocked Jammu and Kashmir’s land resources following the unilateral undoing of key constitutional protections, every land-linked issue eventually lands into an identity-demography debate. This is precisely what happened to the Prime Minister’s AwasYojna (Grameen) under which the government offers support of Rs 1.20 lakh to homeless people for building their homes.

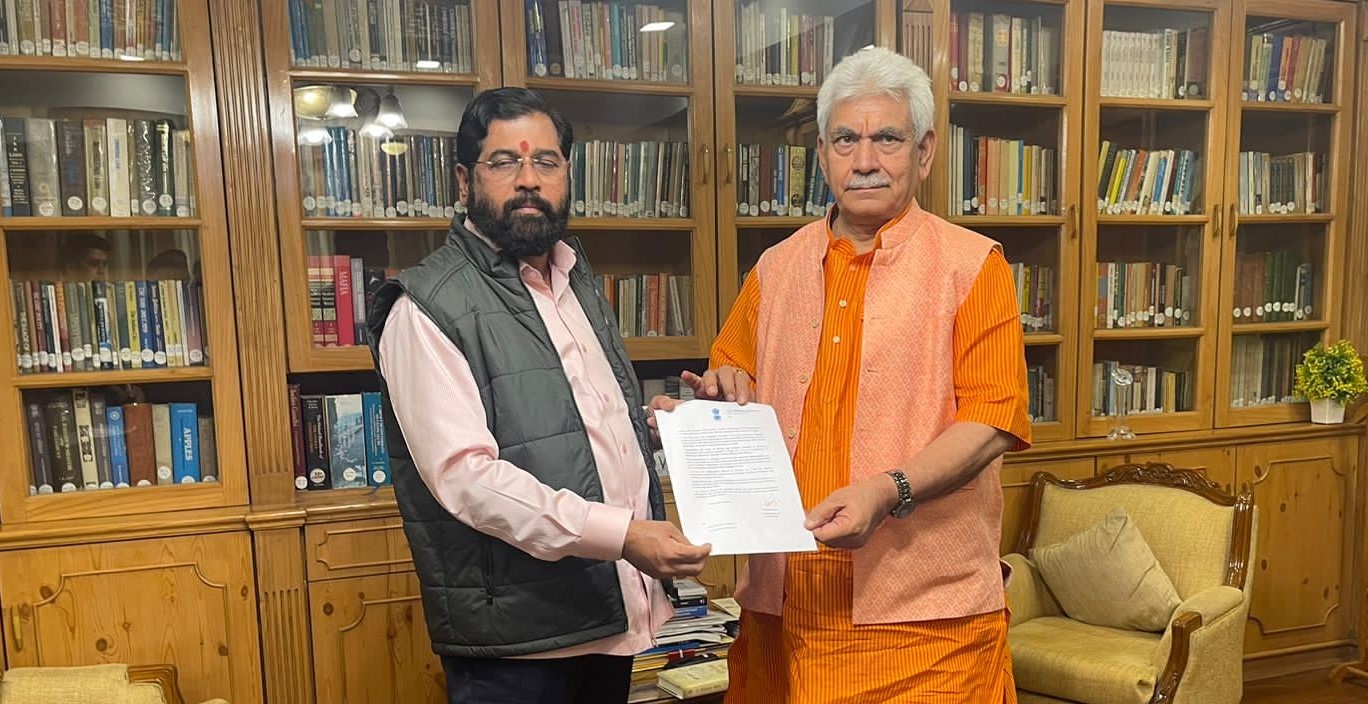

In July, Lt Governor Manoj Sinha addressed a news conference announcing that the administration is offering 5 marlas(1360 sq ft) of state land to landless families to enable them to avail the PMAY scheme.“We have given plots to 2711 landless families across Jammu and Kashmir. We will be providing land as per the list we have and hope to complete the existing backlog by March 2024,” Sinha said. “The Rural Development Department has identified 1.83 lakh families who do not have their own houses. We are working on it. It is a step that will not only provide a house to them but transform their lives.”

It was supposed to get a fierce reaction. “The LG made an announcement about giving land to 1.99 lakh landless people in JK,” former Chief Minister, Mehbooba Mufti said, doubting the numbers as 2021 figures by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs suggested Jammu and Kashmir has only 19047 homeless families including 10,000 in rural areas. Assuming that a family will have a minimum of five people, it was a matter of a million heads. Insisting attempts to “unpeople” Kashmir, she said, region’s resources, under “a dangerous game” are being treated as “war booty”. “Is the government counting those as homeless who came here just a week ago and are claiming land in J&K? Those who came to J&K after 2019 should not be part of this scheme,” Omar Abdullah, another former chief minister, wrote on Twitter.

The quantum jump in the number of homeless is still an enigma within and outside the political class. In 2021, the number was 19047 and in 2023, it is nearly two lakh families.

The Rebuttal

Angry, the Rural Development Department (RDD) that spearheads the scheme issued a rebuttal. A 2016 survey identified 257349 cases and verification reduced the number to 136152.

Between January 2018 and March 2019, the Government conducted Awaas+ survey to identify beneficiaries who claimed to have been left out under the 2011 SECC. “PMAY Phase-II(Awas+) Grameen started from 2019 onwards based on a survey of 2018-19, (done pan India), in which 2.65 lakhs houseless cases were recorded in J&K and only a target of 63426 houses was given to J&K. These houses have been sanctioned in 2022 only,” the rebuttal reads. “Based on a good performance of J&K in sanction and completion of houses, on 30th May 2023, 199550 more PMAY Awas+ houses have been sanctioned as a special dispensation, in order to ensure housing for all for all 2.65 lakhs houseless persons.”

An Explanation

Explaining the crisis, a senior RDD official said in 2011 when enumerators made door-to-door surveys, they asked women about the facilities like TV, fridge and other facilities at their homes. “A lot of women admitted to having TV and other things though the fact was they never had it. This, they did, for the family prestige,” the officer said. “When this data went to different ministries, all those families claiming to own these facilities became ineligible for the home facility, something that was realised by the government of that time as well.”

In 2017-18, when the RDD carried out a survey in Kashmir, they found 13200 homes under different stages of implementation under the scheme as more than 52000 were waiting to be covered under the scheme. In June 2023, when a fresh survey was carried out by the department, only 29000 were found to be eligible because “the rest of them had crossed the threshold and improved their situation” – some had got a job and most of them had built a house. “In Kashmir, right now, there are only 29000 odd families that can be covered under the scheme and of them, only 210 are landless and will get 5 marlas of land,” the official said. “Even Jammu has a similar number but the landless are slightly higher.”

Even though the numbers still require a lot of explanation, officials insist that there is no scope for any non-local to get benefited from the scheme.

Land Redistribution

The AwasYojna debate, however, re-links the use of land by the rulers as a key resource for one or the other reasons throughout the history of Kashmir. Sometimes it was given out as a dole, sometimes as part of exploitation and, at times, it was fundamental to the socio-economic well-being of the society. Land redistribution has remained a continuous feature of Kashmir’s history and is expected to remain so. Kashmir always had limited land resources and now in the twenty-first century, it is under serious pressure for the first time.

People living in a territory have ownership of the land they live in. This right was later taken over by the rulers and in Kashmir, the residents lacked the right to their land resource ever since the fall of Chak rule. Subsequent rulers manipulated the land resource to fund the exchequer of the machinery they led.

All kinds of land “ownership” were cancelled by Gulab Singh after he purchased Kashmir and claimed absolute rights over everything. In a bid to create his own support base, he confiscated 3115 Jagirs and redistributed land among the Jagirdars of his choice to create his own ‘landed aristocracy’. The residents were reduced to serfs. As people would cultivate the lands, the soldiers would appear at the time of harvest and take away more than two-thirds of the produce. This triggered a serious crisis and people stopped cultivating lands forcing the depots to raise special battalions to force cultivators to work.

Jagirdars, Chakdars, Mukarraries and Maufidaars have all been various forms of landlords who were ruling the roost in Kashmir for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most of these landlords were close and distant family members of the rulers, courtiers, loyalists and those sharing the same faith. Later in 1877, Maharaja Ranbir Singh even brought in a huge group of Mian Rajputs from Jammu and gave them vast swathes of land in Kashmir periphery in order to create a cushion for him “in case of a disturbance”.

Under pressure from British India, the depots eventually gave in to the land settlement and a number of top officials were given the job. It started with Andrew Wingate and concluded with the hugely popular Walter Lawrence.

The First Benefit

It was after a long exercise carried out by Lawrence that a suggestion was accepted by the durbar. The idle land in the villages was supposed to manage the community priorities like graveyards, shamshan ghats, religious spaces, toilets and bathrooms. Whatever remained was distributed to the farmers in proportion to the land they were tilling, on pro-rata basis. This land is called Shamilat was to be tilled by the farmers without offering durbar any land revenue, Maliyat.

“The process started in 1924 and was accepted by the durbar in 1926,” revenue expert and author on revenue issues, Syed Farooq Bukhari said. “The scheme, apparent a major intervention, was implemented in Jammu in 1927. In Kashmir, it remained in limbo and was implemented in 1932 only after a British officer-led commission made a recommendation.”

This was a major reform and has been recorded by the official history as well. “On the occasion of the Rajtilak ceremony, which was performed at Jammu in February 1926, in the presence of distinguished guests including several Ruling Princes, His Highness announced a number of boons,” the Jammu and Kashmir’s Administrative Report for 1943 reads. “One of the boons conferred on the land-holders the right to cut down and utilize all royal coniferous trees on areas assessed to land revenue; another extended from 3 months to 12 months in the year the right of the villagers to remove dead and fallen timber; and a third bestowed certain rights on village communities with regard to the land of land-holders dying without issue. The most important of the boons was the bestowal of khalsa land on village communities which had no shamlat (village commons) up to cent, per cent, of their holdings.”

History gives credit to Maharaja Hari Singh for taking the decision, which has given people “almost propriety rights” over the Shamilat lands, a system that is still in vogue. As the people started cultivating these lands, the production improved and hunger, the permanent resident of Kashmir, was managed better.

Land to Tiller

Partition changed things across the subcontinent. The Maharaja rule collapsed and Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah led an emergency administration in Jammu and Kashmir.

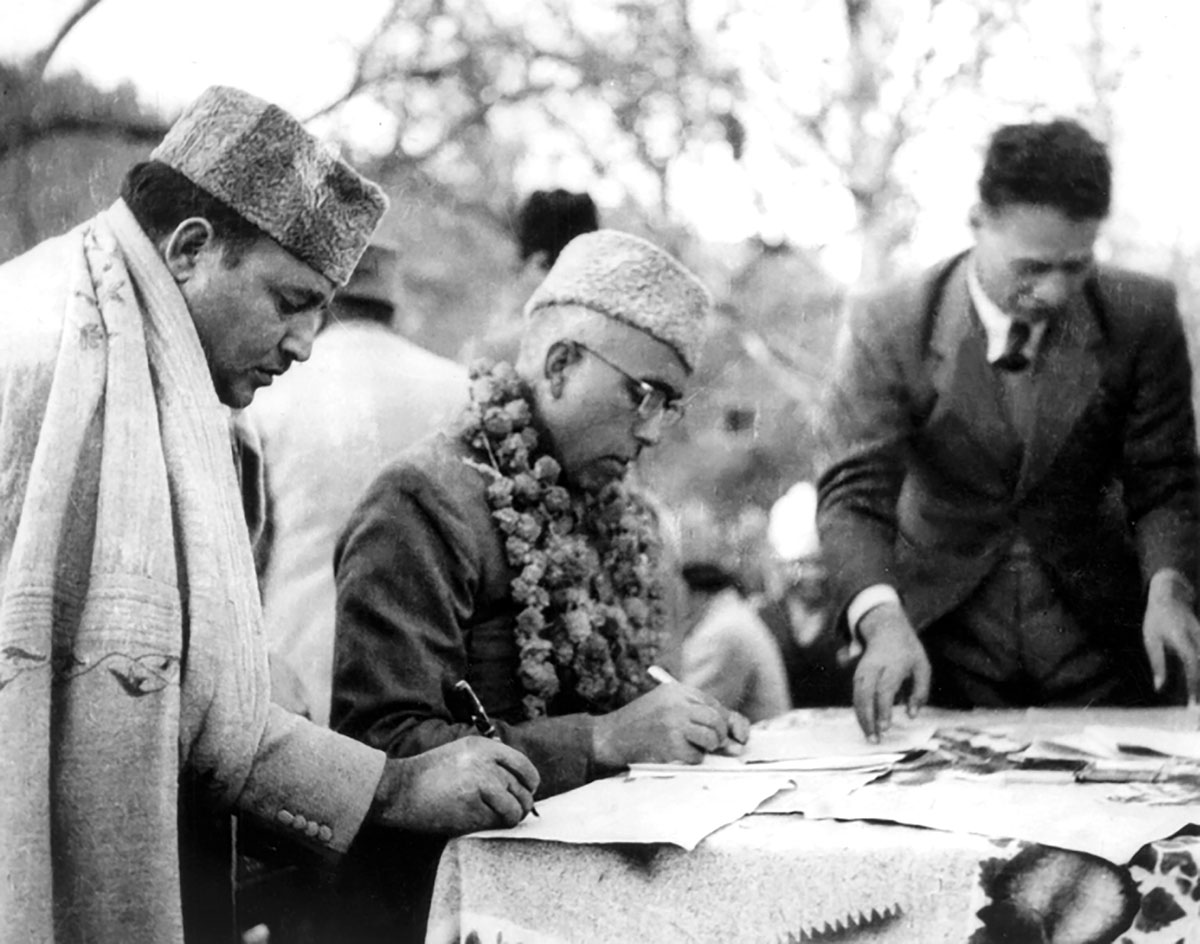

“After abolishing the Jagirs and Muafis by the Tenancy Act of 1948, restrictions were placed on the right of the landlord to eject the tenant, by the Tenancy (Amendment) Act of 1948. The landlord was, however, given the right to resume the land from his tenant if he required it bona fide for personal cultivation subject to a ceiling on his right of resumption,” a division bench of the Supreme Court explained the intervention in the Prem Nath Raina case in 1983. YV Chandrachud led the bench. “The Big Landed Estates Abolitions Act of 1950 was quite a revolutionary piece of legislation in the context of those times. A ceiling was placed by that Act on the holding of properties at 182 Kanals, which comes roughly to 23 acres. The land in excess of the ceiling was expropriated without the payment of any compensation and the tiller of the soil became the owner of the excess land.”

It was the only case in the Indian subcontinent where non-compensatory land reforms were implemented on a war footing. Influential individuals holding vast estates were divested of lands beyond 22.75 acres. Between 1950 and 1954, on the basis of this revolutionary legislation, 196597 acres of land were taken away from landlords and transferred to 112867 peasants who were tilling these lands for many centuries.

Though Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah was dethroned and arrested in a coup that the central government ensured through his deputy, Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad, the latter ensured the land reforms are implemented with an iron hand.

Managing Refugees

The partition triggered serious demographic upheavals. Tens of thousands of people were killed in India and Pakistan, the two sister nations that became free. Unlike Kashmir, Jammu witnessed a serious communal massacre. As the situation eased, two types of people entered Jammu and Kashmir – the Displaced Persons (DP) and the Sharnarthis. The DPs were state subjects who were living within Jammu and Kashmir in areas over which Jammu and Kashmir lost control and Sharnarthis were West Pakistan Refugees (WPR).

Official records suggest 31619 DP families migrated to Jammu and 26319 of them settled within Jammu and Kashmir. The government allotted them more than a million kanals of land including around 700 thousand kanals which fleeing Muslims had left behind in Jammu.

The numbers about the WPR were in dispute. The then Revenue Minister M N Koul informed the state assembly on March 16, 1971, that only 2752 WPR families are in Jammu and Kashmir. Dr Karan Singh, the erstwhile Sadr-e-Reyasat told The Statesman on March 25, 1981, that there were around 3000 families from Sialkot and 90 per cent of them were Harijans. On August 30, 2007, the government told the Panthers Party founder Bhim Singh in the state legislative council that J&K has 4745 families WPRs comprising 21979 souls.

But the numbers changed after a committee led by IAS office G D Wadhwa, the then Financial Commissioner, submitted his report on November 29, 2007. He put the WPRs number at 5764 families comprising 47215 souls who are scattered in Jammu, Kathua and Rajouri districts.

Under Cabinet Order (No 578-c of 1954), the Committee said the WPRs were given the right to use over 46466 kanals of land on the basis of either 12 acres of Khushki or eight acres of Aabi. Now, for the last five years they were covered under a special rehabilitation scheme of the central government and post-2019, they were given all the rights that the state subjects had.

A Follow Up

By the time the Indira Abdullah accord was being negotiated, the Jammu and Kashmir government had already located the loopholes in the earlier land laws. Various laws were passed. These included the Tenancy (Amendment) Act of 1950, the Tenancy (Amendment) Acts of 1956, 1962 and 1965, the J & K Tenancy (Stay of Ejectment) Proceedings Act 1966 and the Agrarian Reforms Act of 1972. These legislations ensured the tenants are protected in the matter of rents, and certain classes of non-occupancy tenants came to be regarded as protected tenants and landlords were given a further opportunity for making applications for the resumption of land. Landlords filed thousands of applications under the provisions of the Tenancy Amendment Act of 1965 for the resumption of lands from tenants but, later, further proceeding in those applications was stayed. At least two major commissions were appointed to identify the problems in land redistribution and settlement and suggest solutions.

“When the big land estate law was passed the ceiling was done per head and not per family. This resulted in the bigger landlords dividing their holdings among their family members. There was absentee landlordism as well in which the landlords were not cultivating their lands personally,” Bukhari said. “Addressing all these issues, the Jammu and Kashmir Land Reforms Act 1976 reduced the ceiling of land holding to 12.50 acres.”

This decision gave more land to the tiller. Details suggest that between 1980 and 1985, around 308000 tillers got ownership of over 106000 acres of the land, which they were already cultivating.

In Between

There were many other interventions at the governmental level that led to the change in land ownership beyond the much-talked-about land to tiller and Zar-e-Islahat legislations.

In around 1958, the government carried out a survey that suggested that a lot of people are in occupation of state land. While they were using the land resource, the government was not getting any revenue from the operations. The then government came with an order, known in revenue circles as LB6. Under this order, all the Kabza Najayez was acknowledged and the occupants were told that they have to pay the government a share but the ownership of the land shall remain vested with the government. They were occupying these land parcels tabei marzi-e-sarkar.

Later in 1966, the then Chief Minister, GM Sadiq issued order 432 bestowing the ownership rights to the occupants of all the lands under LB6 across Jammu and Kashmir.

Later, many parcels of land were given out at 5 marlas per family to many houseless people across Jammu and Kashmir in the post-1975 Sheikh Abdullah era.

Darkness of Roshni

Frustrated over the failure of managing the financial closure of the upcoming 450-MW Baglihar Power Project, Dr Farooq Abdullah led the National Conference government and finally decided to give ownership rights to all the land grabbers on the basis of the market rate. It was supposed to generate Rs 20,000 crore that was supposed to fund the major power projects.

Barring the legislation, the NC government could not do much because the 2002 election brought a PDP-Congress coalition into power. Initially, the Mufti government was reluctant to touch the scheme but as it also started suffering for the Baglihar funds, it pushed it to the next level. Rules were drafted and systems were put in place. The Jammu and Kashmir Bank was asked to devise a scheme that will fund the debts required by individuals to secure ownership rights.

After revenue officials made the assessments, people started paying the cost and claiming their rights. In Kashmir, the government gave ownership rights over 13732 kanals and pocketed Rs 54.27 crore. In Jammu, 158512 kanals were given against a paltry sum of Rs 22.64 crore.

The scheme had picked the pace and then the transfer of power took place and Ghulam Nabi Azad succeeded Mufti Sayeed. He interrupted the scheme twice. In the first go, he gave concessions of up to 75 per cent of the market cost. In the second intervention – using assembly for an amendment, he gave the land grabbers the land free and made the revenue department ensure mutations at Rs 100 and deliver the ownership rights to the encroachers at their doors. This devastated the scheme. Even the bureaucracy was unhappy.

Later, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) came up with a devastating report and it eventually led to annulling of the scheme by the then-governor Satya Pal Malik in 2018. Now countless cases are in the court of law. This has been the worst ever land redistribution in which the law-violators were incentivised.

Post-2019

After the reading down of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status and binning its constitution, most of the land laws were binned or repurposed. AS many as 12 land laws were repealed. These included the Jammu and Kashmir Alienation of Land Act; Jammu and Kashmir Big Landed Estates Abolition Act; Jammu and Kashmir Common Lands (Regulation) Act 1956; Jammu and Kashmir Consolidation of Holdings Act 1962; Jammu and Kashmir Right of Prior Purchase Act, and the Jammu and Kashmir Utilisation of Lands Act.

The order issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs under the Reorganisation of Jammu and Kashmir Act, amended, substituted or re-purposed 26 other land laws to open the limited land resource for investments in the industry and services sector.

As the land resource was opened for investors at a premium under the new industrial policy, officials said nearly 2000 new investors have been allotted land across Jammu and Kashmir. Investment in the industrial sector had been a continuous process since the Vajpayee era scheme but the new scheme announced by the Narendra Modi government is hugely attractive. Insiders believe the scheme is more of a service sector plan rather than an industry investment scheme. They allege most of the existing industrial units are gradually sinking as the new scheme has done away with the cushions that existed earlier.

However, most of the new investments are reportedly taking place in the Jammu region because of its closeness to the market and the rail head.