The fresh water resources of Kashmir valley are under serious threat as glaciers that feed have vanished or are receding fast. While scientists put the blame on global climate change, Kashmir appears to be moving towards an impending disaster. Ahmad Riyaz reports.

Glaciers in Valley are retreating fast, creating a distinct scenario of a Kashmir without its fresh water streams. Triggering alarm bells is the slowly shrinking Kolahai glacier, the biggest in Valley which experts predict may altogether disappear, triggering the spectre of a reduced discharge in river Jhelum which in turn might bring water to the forefront as the main dimension of the Indo-Pak dispute over Kashmir.

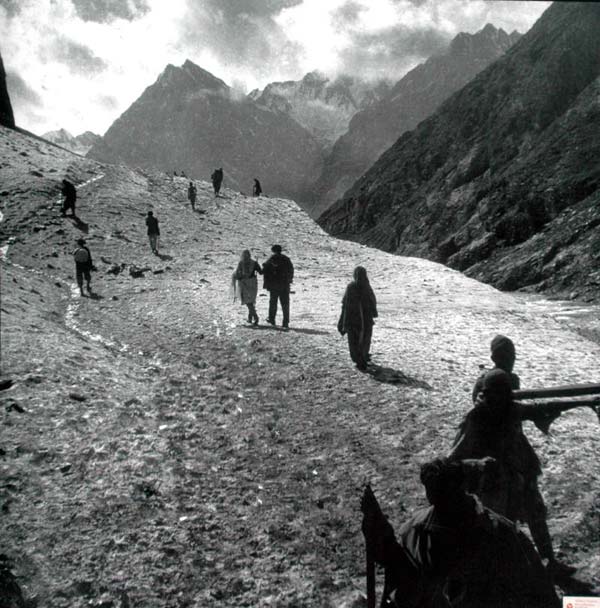

The area of Kolahai, says the climate change expert Dr Shakeel Ramshoo has retreated from 13.87 square kilometers to 11.24 sq kms from 1976. “The annual rate of retreat is 0.08 sq km, which is quite alarming,” says Romshoo, who is convener working group, Climate Change Research at Kashmir University. At an altitude of 3600 meters in the upper reaches of Pahalgam tourist resort, Kolahai is the source of Lidder and Sindh, two major tributaries of river Jehlum and one of the most valuable natural gifts (resources) of the Valley.

The situation is no different with other glaciers. An Action Aid Report says there has been an overall 21 per cent reduction in the glacier surface area in the Chenab basin. “The mean area of glacial extent in the state has also declined from 1 sq km to 0.32 sq km from 1962 to 2004,” the report says. Many of the areas, the report adds, have seen a complete disappearance of small glaciers such as some parts of eastern Srinagar and Pirpanjal mountain range in district Pulwama. “In other areas, like Budgam, the height of the small glaciers has reduced to over one-fourth of the original height”.

Similialy, the upper reaches of the Sindh Valley in Ganderbal district, the Najwan Akal which was said to be a major glacier, has completely disappeared today. Thajwas, Zojila and Naranag glaciers which once used to last up to October through November till a few decades back too have considerably reduced. The report says the length of the Hangipora glacier in Islamabad has reduced from 35ft to 12ft and the Naaginad glacier has reduced from 30ft to 10ft.

However, it is Kolahai, one of the major glaciers of the Himalayan region that worries the climatologists more. For, it is the source of Valley’s many fresh water streams without which Valley would not only diminish considerably in its physical beauty but also lose its soul. Dr Ramshoo, however, apprehends a bigger danger: “If the recession of the Himalayan glaciers goes on at this rate, the discharge in state’s rivers would substantially go down. We could have a serious problem at hand in another thirty years with water dimension of Kashmir completely obscuring its political dimension”.

Dr Romshoo is leading the study on Kolahai in Valley and Suru basin glaciers in adjoining Kargil – a project sponsored by ISRO which began in 2007. Like Kolahai, the glacialised area of Suru, which was about 72 sq kms 40 years back, has shrunk by 16.43 percent and dozens of its around 300 glaciers have already vanished.

What is causing the change in Kashmir is the increase in temperature Kashmir that is above the global average. “The increase in Kashmir temperature has been 1 degree centigrade which is substantially more than 0.72 degree centigrade rise in global temperature over the past century as per The International Panel on Climate Change,” says Dr Ramshoo. “The result is less snowfall and less formation of glaciers”.

This ongoing climate change is also affecting the nature of Kashmir conflict between India and Pakistan. Water is fast emerging as the new bone of conflict forcing last year even Jamaat-u-Dawa chief Hafiz Saeed to mention it as one of the important reasons for waging militant struggle in Kashmir.

Pakistan is seriously concerned that the several glaciers situated in Kashmir Himalayas are shrinking, resulting in a recession in the levels of water that flow in rivers originating from these glaciers. Subsequently, agriculture is getting affected while availability water for drinking and other domestic purposes is witnessing a decrease. Pakistan’s water availability has decreased to 1,200 cubic meters per person from 5,000 cubic meters in 1947 and is forecast to plunge to 800 cubic meters by 2020.