by Khursheed Wani

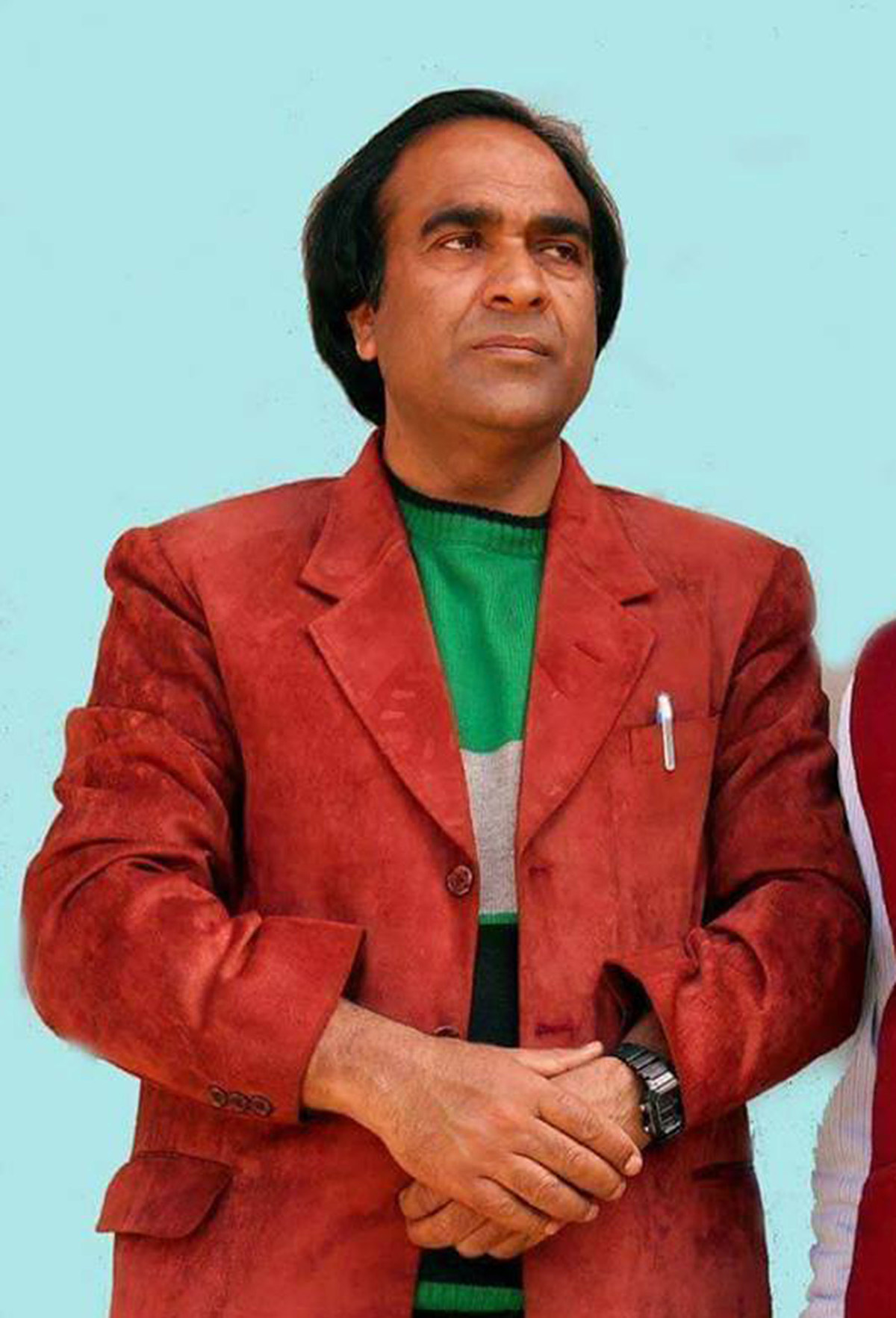

A few days ago, I was rushing towards a TV studio to conduct a current affairs programme when Maqbool Sahil waylaid me to exchange pleasantries. He was clad in a formal dress, wearing a broad smile and greeted me as warmly as was his trademark. This was the last time I saw the man who would have been celebrating his 50th birthday in a few months. On the evening of March 19, he suffered a massive heart attack in Srinagar’s Lalbazar locality and passed away. Sahil’s sudden death shocked his friends, admirers and colleagues. His family is shattered and inconsolable.

Sahil was a distinctive person in conduct, appearance and style. From a calligrapher to an investigative reporter and a photographer to an acclaimed writer, he lived a life full of struggle treading a long path, rough and smooth. To his last breath, he fought adversaries to create a place for himself. Unfortunately, unlike many others, who were no comparison to his intellect and ability, Sahil could not settle himself to the best of his satisfaction. The rough and tumble in his journalistic career reflect the vulnerabilities of reporters working in a conflict region.

Hailing from Khokharpora village near Adhal in south Kashmir’s Kokernag pocket, Muhammad Maqbool Khokhar belonged to a pahari Rajput family. He graduated from a college in Srinagar and plunged into media industry to earn his livelihood. He was a calligrapher with Urdu weekly Azaan where he picked up writing skills and nuances of journalism. In 1990s when anti-India armed movement triggered off in Kashmir, Khokhar quit calligraphy and joined daily Aftab on the desk. He then tried his luck in Bombay to get roles in films but that was not to be. He returned to Valley in 1992 and resumed journalism with his pen and camera. He became visible as a reporter with Chattan, then a popular weekly, thriving on incisive reporting on militancy and politics. He was always seen riding his motorbike with camera bag hanging from his shoulders. He was a sought-after journalist during the hostage crisis of foreign tourists abducted by shadowy group al-Faran. He had cultivated sources within the group and knew some exclusive details.

A twist came into Sahil’s career when he was arrested by the sleuths of counterinsurgency police outside the headquarters of XV corps where he had gone to meet the public relations officer. The US-based Wall Street Journal in one of its reports said that Maqbool was accused by the army of working in collusion with Pakistan’s intelligence agency during a visit to that country in 2000, a charge he denied saying the purpose of his visit was to interview migrants who had left the Indian side of Kashmir for Pakistan. He was charged nine days after his arrest on charges of espionage on behalf of Pakistan’s ISI, the Inter-Services Intelligence.

During his preliminary interrogation, before he was charged and sent to the central jail, Maqbool alleged that he was beaten, suspended by his arms from the ceiling, and had the muscles in his legs mauled by rollers. He told WSJ that officers who conducted the interrogation were army officers he recognized from his time working as an investigative reporter. He said by the time he reached prison he had lost the ability to walk on his own strength.

Ironically, Sahil was left to fend for himself for around 40 months he spent in various jails without being charge-sheeted. There was not even a murmur in his support from his own fraternity. A newspaper disowned him and fellow journalists turned their back. Nobody knew about the ordeal his family of five children and wife faced. Shujaat Bukhari, his post-freedom employer told me that he was the lone journalist who went to see him in lower court of Srinagar where he was brought handcuffed for a hearing. He also met Sahil in Kotbalwal jail.

Bukhari may be hauled over coals for his ‘insensitivity’ to post Sahil’s picture taken shortly after his death on facebook but that does not diminish his role in helping Sahil to return to his passion. When he died he was working with Buland Kashmir, one of the three publications owned and edited by Bukhari.

Sahil was flamboyant. He would engage anyone in long conversations. He had an impressive voice and command over Pahari language that gave him an opportunity to host popular programmes in his mother tongue on radio and television. He also acted in Pahari serials and would boast his contacts with singers and actors. He was quite showy. When there were no cell phones, he would roam around with a limited range cordless phone.

During his incarceration, he penned down his ordeal in chaste Urdu. It was published as Shabistan-e-Wajood and well received by critics. The book earned him an award from Reporters Sans Frontiers, an international organization fighting for rights of journalists. The book also gave him an opportunity to participate in literary festivals across India. He has many books to his credit including Qadam Qadam Tazeer, Urdu poetry collection Khamosh Talatum and Pahari collection Lishkaran. Tanaza-e-Kashmir, his only book on history, delving on the political history of the embattled Valley.

It is unfortunate that Sahil’s death triggered off some avoidable controversies reflecting the sordid state of affairs in the media industry. Sahil was not treated fairly in his lifetime. His family comprising sons Iqbal, Firdous, Umar, Sameen, Salman and the only daughter Yasmeen, should not be subjected to humiliation after his demise. If the journalists want the welfare of his family, they must help it in a dignified way. May his soul rest in peace.