In his latest book, poet historian Khalid Bashir Ahmad has succeeded in deconstructing myths, mysteries, events, individuals and institutions that dominated the troubled twentieth century Kashmir, writes Khalid Bashir Gura

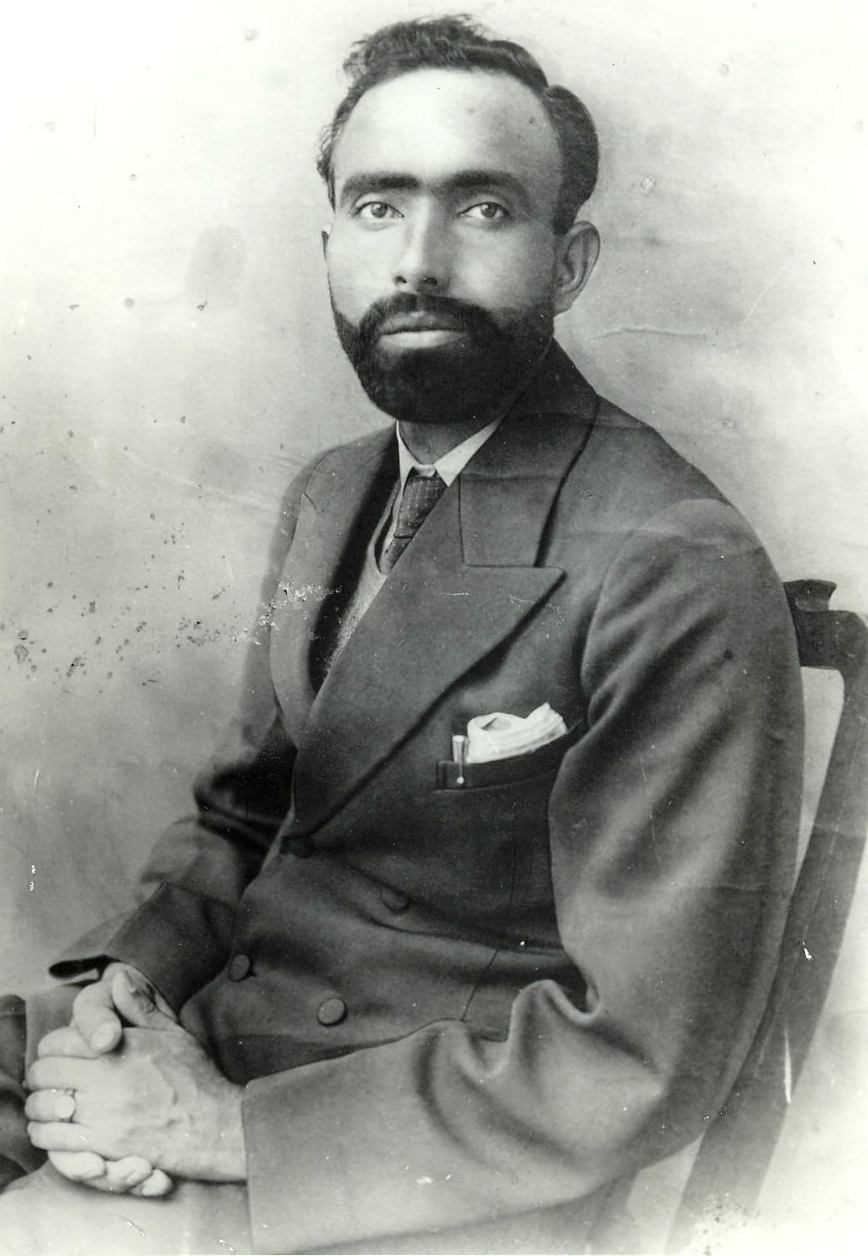

Following the masterpieces that challenged the medieval myths, poet historian, Khalid Bashir Ahmad is back to lift the fog of façade behind narratives, events, and personalities with his rigorous research in his new book, Kashmir, Looking Back in Time: Politics, Culture, History that Atlantic published early this year.,

A riveting historical, the book through its lucid description supported by thorough research and indisputable sources including archival literature, published works, travelogues and eyewitness accounts help readers wade into Kashmir’s turbulent twentieth century. It helps understand the present through the recorded events, personalities, and watershed events. It debunks myths, dismembers cherished ideals and reconstructs history. The book starts with Sheikh Abdullah and ends with journalism in Kashmir. It is full of tectonic shifts in Kashmir’s power politics.

Sheikh’s Politics

At a time when India was nearing its freedom from British Empire, a Kashmir teacher, Sheikh Abdullah, in 1930 plunged into politics then revolving around the basic rights of the people. His foray into politics was set by many macabre events in Kashmir. An eloquent speaker, Abdullah charmed his audience with the melodious recitation of verses from the Quran and couplets of Allama Iqbal soon formed an organization in 1932 named Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference which became a formidable force against the despotic ruler.

It created insecurity within the Kashmiri Pandits who were ruling the roost and enjoying monopoly in the despot’s administration. The organization much to their reprieve, soon saw itself plunged into internal feuds that had preceded the birth of the party between Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah and Mirwaiz Mohammad Yusuf Shah who Sheikh considered as an obstacle to his becoming the sole leader of Kashmir.

Soon, Abdullah, influenced by the secular ideals of the Indian National Congress, especially Jawaharlal Nehru, dissolved Muslim on June 11, 1939, and constituted the National Conference. The flag of the party was changed from a green and white crescent to a red and a white plough.

Some considered it tantamount to breaking the oath taken in the historical meeting on June 21, 1931, with the Quran as the witness. Even his wife, Begum Akbar Jehan in her resistance to dissolution left Sheikh for some time but eventually had to save her family. This event marked the beginning of Sheikh’s frequent goal-shifting and his itinerary to power irrespective of being an administrator to Prime Minister to Chief Minister.

It changed Sheikh. In one of the first public meetings at Rainawari, members from the Hindu minority appeared on the stage wore vermillion on his forehead. He recited verses of Bhagavad Gita and concluded his speech with the slogan Har Har Mahadev.

These gimmicks did not alter the ground realities. The book vividly captures Sheikh at the end of his career, regretting the people he counted as friends and on whose tunes he was acting were not his friends at all.

The book’s first theme deals with politics and Sheikh is pivotal spoke in the cog of Kashmir’s political history. It narrates how he retracted from some of his publicly declared cherished ideals, fighting against the despotic regime and soon ending up taking an oath of allegiance to him and his progeny, a patronizing plebiscite in Kashmir and ultimately calling it a day in exchange for a crown and chair of Chief Minister.

However, the absorbing selective excerpts of commentary on Sheikh does not mention some of his great reforms and initiatives for which he was enamoured and idealized like saint and saviour by the Muslim majority. The book illuminates his power politics, a dictator in democrat, a power-thirsty individual whom absolute power corrupted absolutely and who used different podiums for different goals and messages, who was dismissed and jailed by his cherished bosom friend, Jawaharlal Nehru.

The book also highlights the role of various unionist opportunistic Kashmir politicians who were used by Delhi against each other after buying their loyalties to achieve their ends. Every opportunistic colluded in hollowing out the state’s special status, the book details.

The Cultural Aspect

The book documents and presents the richness and variety of Kashmir culture. It is divided into sub-sections such as Tale of Mammoth Loss; The Celluloid Years; Kashmir to Ka’ba; Changing Place names; Story of an Uptown Quarter; Of Prices and Fairs; Romance and Rumors thus weaving a rich and varied narrative of Kashmir’s loss.

The section raps on the knuckles of inefficient bureaucracy, complicit custodians, archaeologists, scheming outsiders, and corrupt political leaders who have been hand in glove in robbing Kashmir of the valuable rich heritage by art smugglers, and it also documents loss due to natural and manmade calamities.

The Celluloid Years tells the ‘story of the beginning of the colourful journey of cinema in Kashmir and how the beginning and end of cinema halls in Kashmir is linked to the turmoil. It has described people’s inhibitions to going to the cinema to ultimately, it being accepted in the conservative society and it becoming a norm to ultimately its curtains falling down with the onset of militancy in Kashmir and how governments over the years tried to open the cinemas to buy normalcy and narrative.

To the millennial, this chapter will be riveting read as the abandoned cinemas, which have metamorphosed into security bankers speak of history. The chapter gives a peep into the growth and decline of cinema in Kashmir.

The Faith

Kashmir to Ka’ba is a vivid account of the arduous journey undertaken by the Kashmiri devout to perform Haj and explored its sociological contours and the essence the ritual carries in the society. The book records the transformation the ritual has gone through as a result of fast means of travel globally.

The Changing Place names bear similar resonance to the present practice of changing names and tells a lot about the politics behind this phenomenon.

The Story of an Uptown Quarter the growth and transformation of the once sleepy village of Sonawar to the favourite abode of rulers, bureaucrats, and foreign tourists is a good read but one wonders how can the people, places, history, events of Shahr-e-Khas miss in the book, which has themes of politics, culture, and history?

The sub-section Of Prices and Fares takes the reader through the absorbing details of prices and fares when essential commodities’ cost was abysmally low but it will be naïve to imagine one could afford any of the luxuries easily.

Romance with Rumors narrates how rumours have been rife since the beginning in Kashmir and why. Rumours have also been used as a political tool to valorise and demonize, and how many rumours became beliefs of ardent followers. It also gives a general peep into the psyche of inhabitants as to what they believe and want to and when. Every watershed event has entailed this trait and critical thinking takes a backseat when it comes to Dapaan!

Allama Iqbal

The book finally chronicles the oppression of the despots and resistance against their policies. It narrates interesting tales related to the affairs of governance and individuals at the helm. It sees Allama Iqbal as a sympathizer with the Kashmiris who spoke, wrote, and mobilized public opinion about the plight of his ancestral land but his detractors deconstructed his sympathy as sinister designs and a craving to become the Prime Minister of Kashmir.

The book talks about the 1939 Kashmiri Pandit agitation against the Dogra regime over the government takeover of temple management in Srinagar. The protestors protested in varied ways and how the city was engulfed in chaos and confusion till settlement. The chapter seems out of place without any real essence to the overall history.

It is followed by the Dogra regime and the overview of the psyche of administrators, dubious characters, and modus operandi of the government. It also mentions the different people history of Kashmir witnessed and changed its appearance with time. There were superstitious rulers, collaborative Molvis, passport-seeking beggars, a snooping resident, and other characters who throw the light on times and places.

Similarly, A Bowl of History narrates Gulmarg and its European visitors with important historical and cultural developments. The book narrates the history of the place to its development to the people who visited the hill station to those who created laws and wanted it to be developed for recreational activities.

The Media

Finally, the book offers a detailed account of journalism in Kashmir that sketches its birth, the era of censorship to growth. Unlike his predecessors, the last ruling scion of the Dogra dynasty, Maharaja Hari Singh (1947-47) gave some leeway to journalism. Later as the regimes and times changed so did the media landscape in Kashmir. The present state of media needs to buy courage from the past as history is repeating itself.

This work must be made compulsory reading for all college and university students. It will enhance the understanding of the past though not completely. The book through its meticulous research and author’s access to resources eloquently brings together what could otherwise be scattered beads of history. He picks the threads and joins the dots to create an incisive and critical narrative.

To comprehend the present and move towards the future requires an understanding of the past: an understanding that is sensitive, analytical, and open to critical enquiry, the book is an attempt at it. It is the beginning of a historical renaissance in Kashmir as now Kashmiris are writing their own stories, history! The book leaves the reader with questions that can be explored through further research.