Kashmir has been written profusely in the last few centuries. Not every traveller has been kind to Kashmir and its people. J F Foster, an Assistant Surgeon in the British army, who spent the peak summer in Kashmir in Ranbir Singh era on medical leave was different from many others in his observations

August 23, 1868, Sunday: We continued to progress last night by moonlight long after the sun had set, and started again very early this morning, so that the Tukh-ti-Suliman (Soloman’s Throne) and Fort are now visible, and I expect to reach Sreenuggur before noon. It is faster work floating down the current than towing against it…

I have again encamped in the Chinar Bugh, but not quite in the old position as a better place was unoccupied. Indeed I had my pick of the whole, for there is now nobody here but myself. I received news (in my letters) that a field force had left Pindee to operate against some of the hill tribes between Peshawur and Abbottabad – ruffians who are always giving trouble, and who occasioned the inglorious Umbeylla campaign a few years ago. I informed my “boy” that there was going to be some hard fighting, and his reply was “With our troops, Sir?” Our troops! good heavens! a black man speaking to me of “our troops.” It is customary I know to call these Asiatics our fellow-subjects, but I never before had the fact so forcibly brought before me.

August 24th: I got up early this morning and have spent half the day on the “Dul” or “City Lake” – a large sheet of water which lies at the foot of the hill behind Sreenuggur. Besides the excessive beauty of the lake itself, there are many objects of interest to be seen on its banks. I visited in succession the Mussul Bagh, Rupa Lank or Silver Isle, Shalimar Bagh, Suetoo Causeway, Nishat Bagh, Sounee Lank or Golden Isle, and floating gardens. A word or two of description for each.

The Munshi Bagh is a large grove of fine Chenars planted in lines so as to form avenues at right angles to each other. There must be several hundred of these noble trees upon the ground, I do not mean fallen but erect and vigorous.

The Shalimar Bagh is an extensive and well-cultivated pleasure garden with pavilions, tanks, canals and fountains, in true oriental style. The upper pavilion is especially worthy of notice having a verandah built of magnificent black marble veined with quartz containing gold. It is surrounded by a large tank possessing one hundred and fifty-nine fountains, and its exterior is grandly if not artistically painted.

The Nishat Bagh is smaller but scarcely less attractive. It is arranged in a series of fifteen terraces, from which a splendid view is obtained of the lake and adjacent country. Down its centre runs a canal, expanding at intervals into tanks and having a waterfall for each terrace, with a single straight row of fountains numbering more than one hundred and sixty. Grand hills rise immediately above it. It contains pavilions of fruit trees, and as a flower garden, is superior to the Shalimar Bagh.

The Suetoo Causeway is a series of old bridges and embankments which formerly crossed the lake, and was two or three miles long, but only portions of it now remain. The two islands are small and covered with trees, having no interest of themselves, but adding greatly to the appearance of the lake. They are I believe artificially constructed.

The celebrated floating gardens are very curious; they were formed by dividing the stalks of the water weeds near their roots, and sprinkling the surface of them with earth, which sinking a little way was entangled in the fibres and retained; Fresh soil was then added, until the whole was consolidated, and capable of bearing a considerable weight. The ground is now about nine inches thick, floating upon the surface of the water, and the stalks of the weeds below it having disappeared. It is exceedingly porous and is used for the cultivation of watermelons, when walking upon it a peculiar elasticity is perceived, accompanied with a tremulous or jelly-like motion. It is divided into long stripes pierced by a stake at each end, which secures them in their position and allows of their rising or falling with the height of the water.

An unlucky day for Silly. In the first place, he was sea-sick. The use of the broad paddle in a small boat caused a good deal of shaking, and every stroke is attended with a sharp jerk forwards – secondly, he mistook a collection of weeds for dry land and jumped out into the water. This puzzled him immensely, and after he was recovered he sat for a long time gazing with a bewildered air upon the surface of the lake. Paid a visit in the afternoon to Sumnud Shah for the purpose of replenishing my exchequer, but found his shop better calculated to exhaust it. I’ll not go there again.

August 26th: There was a great fire in the town last night; three hundred houses have been destroyed. I went early to the scene of the disaster, which is on the left bank of the river adjoining the first bridge. The embers were still smouldering, and among the ruins the heat was intense, owing to the houses having been built almost entirely of wood, little but ashes and charred logs remained of them. Here and there a few hot bricks retained the semblance of a wall, but the destruction has been as complete as it is excessive. The bridge has also suffered, the bank pier having been attacked by the flames, and half the railing on either side of the footway has been torn off and precipitated into the water.

The latter injury was caused I imagine, by the rush of the crowd over it at the time of the fire. No lives lost I believe.

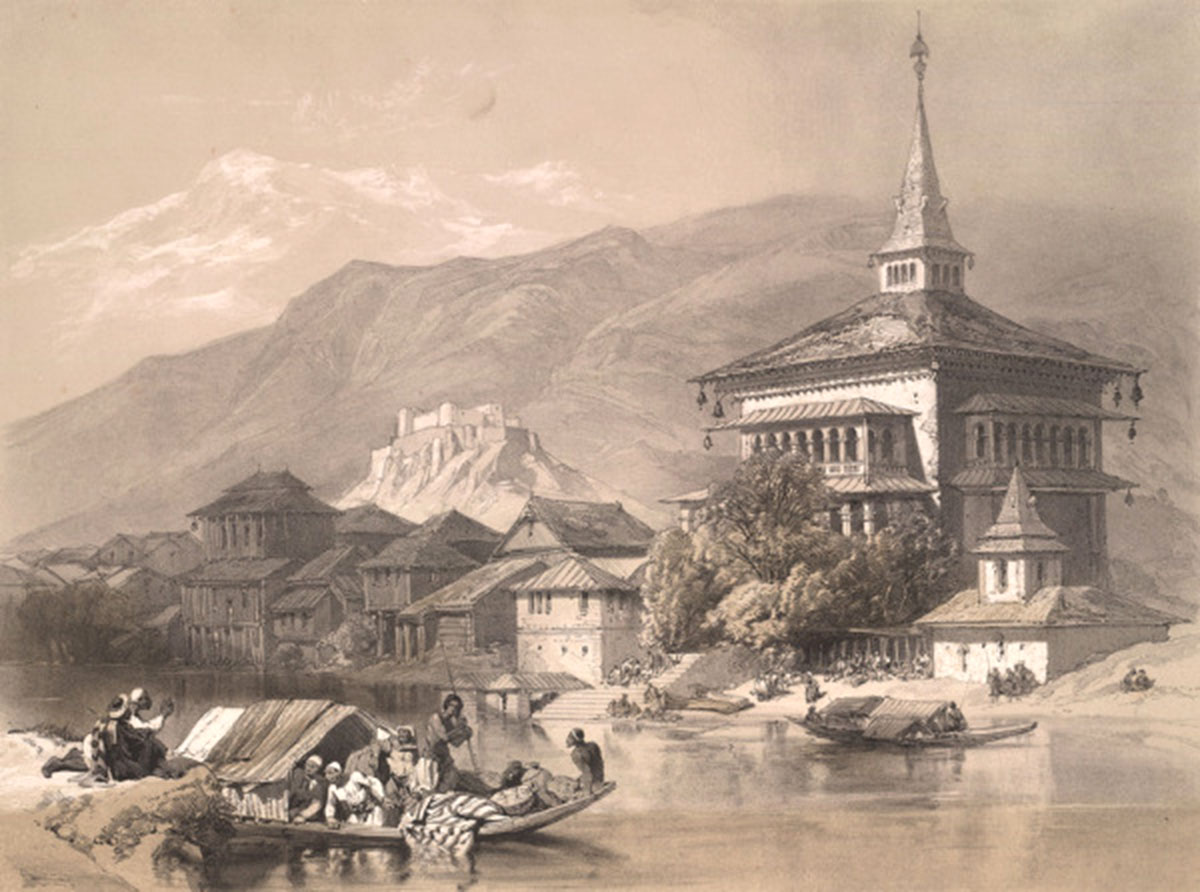

August 27th: At six o’clock this morning a Jemindar or military officer made his appearance, sent by the Baboo, for the purpose of conducting me over the fort. A row of a mile down the river and half a mile walk through the narrow rough crowded and stinking streets of the town brought us to the outworks, at the foot of the hill on which it is built. This hill is very steep and several hundred feet high, and the climb up it was fatiguing. From the top, there is an extensive view, but the morning was misty and the greater part of the valley indiscernible. In front lies the town, intersected by the Jhelum; a great desert of mud-covered roofs presenting anything but the green carpet-like appearance described in books. On the left long lines of poplars, enclosing the Moonshi Bagh and the various encamping grounds, with the Tukh-t-i-Suliman rising high above them.

Behind, the Dul, spread out like a sheet of silver with the background of mountains, and many canals radiating and glistening in the sunlight. Of the fort I have but little to say. From below, its position renders it imposing, but a nearer inspection dispels the illusion. Inside it there is a Hindoo temple, two or three tanks filled with green, slimy water, and some wretched hovels for the occupation of the garrison. The ramparts though high are weak and a few shells dropped within them would blow the whole place to pieces. The ordnance consists of four ancient brass guns; two of them about 9-pounders and the others 32-pounders, but I did not see a spot from which either of them could be safely fired; and even if there were bastions strong enough, I doubt if cannon could be depressed sufficiently to sweep the precipitous sides of the hill.

On my way back to the boat, I turned aside to visit the Jumma Musjid, or chief Mosque, a large quadrangular wooden building, the roof of which is supported by deodar columns of great height, each pillar being cut out of a single tree, but I cannot waste more time over it, the name recalls to my memory the magnificent Jumma Musjid of Delhi – but comparisons are odious. When parting with my attendant, I felt uncertain whether or no he would be offended by the offer of a remuneration for his trouble, so I left him to ask for it, as natives usually do not scruple to request “bucksheesh” for the most trifling service, but either his orders or his dignity prevented him from soliciting it, and he went away unrewarded and I doubt not dissatisfied.

After noon I went and selected a lot of papier maché articles, and gave monograms to be painted upon them. Their papier maché is fairly made, elaborately painted and moderate in price.

At this shop they prepared some Ladâk tea for me, a most delicious beverage possessing a delicate flavour such as I have never before tasted in any tea. It was sweetened with a sort of sweet-meat in lieu of plain sugar.

August 29: Went up to the Tukh-t-i-Suliman (Solomon’s Throne) before breakfast. It stands one thousand one hundred feet above the town and the ascent is effected by means of unhewn stones arranged in the form of a rough flight of steps built by the Gins, I should fancy for their own private use and without any consideration for the puny race of mankind that was destined to follow them. I am a tall man and gifted with a considerable length of understanding but the strides I was obliged to take – sometimes almost bounds – if calculated to improve my muscles were certainly very trying to my mind. However, all things have an end, and so had that long flight of steps, and at the summit, I had the leisure to recover my breath and enjoy the magnificent view.

I took care to have a clear day for this excursion, and the whole valley was seen stretched out like a map, and spreading far away to the feet of its stupendous mountain boundaries. The lakes like huge mirrors reflecting a dazzling radiance. The Jhelum twisting like a “gilded snake” and forming at the foot of the hill the original of the well-known shawl pattern; miles upon miles of bright and verdant fields, divided and marked out by the banks and hedges; clumps and groves of lofty trees diminished by distance to the appearance of mere dark green bushy excrescences; the poplar avenue looking like two long and paralleled lines drawn upon the ground; the fort and hill but a pigmy now; the city of sombre colour, with its houses closely huddled together and presenting an expanse of mud – unworthy stone for such a setting! The high and rugged mountains on every side piercing the clouds, out of which the everlasting snow and ice rock regions untrod by mortal foot gleam and glisten coldly in the scene below; these are the constituent parts of a view which taken altogether ranks among the finest (if indeed it be not itself the finest) in the world.

But I have no description for it as a whole, words would fail me if I attempted to reproduce it on paper, so you must take the items and arrange them to your own satisfaction, and wish you had the opportunity of seeing the glorious original. I am no antiquarian, but I believe the building itself possesses great interest for those who indulge in that musty study, on account of its vast antiquity and uncertain history. To me it is only a Hindoo temple of quaint architecture and unwholesome smell. Inside it is a small marble idol in the form of a pillar with a snake carved round it.

August 30th: … As I sit under the shade of the Chenars writing, a young native swell is passing along the opposite bank of the canal – a mere boy, with gold turban, lofty plume and embroidered clothing, riding a horse led by two grooms, followed by attendants also mounted, but sitting two on a horse and preceded by a band consisting only of some six drummers. He is playing his part doubtless very much to his own satisfaction, and little thinking that there is one “taking notes” and laughing at his proceedings. But so it is, we can always see, and ridicule the faults and foibles of others, would to God we could as easily perceive and weep over those of our own.

The Baboo Mohes Chund called to pay his farewell visit to me and shortly afterwards sent a second edition of “russud” including as before – a live sheep.

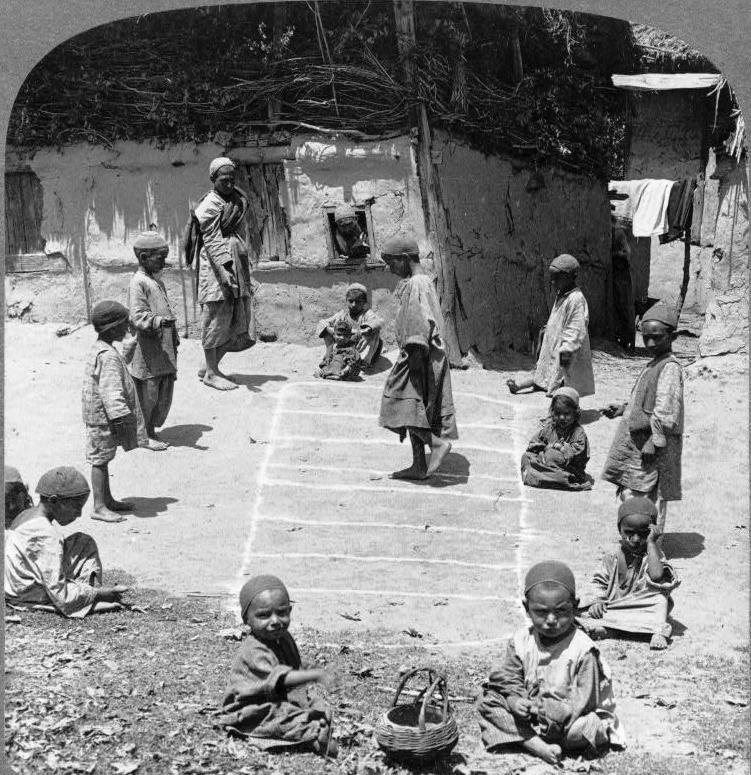

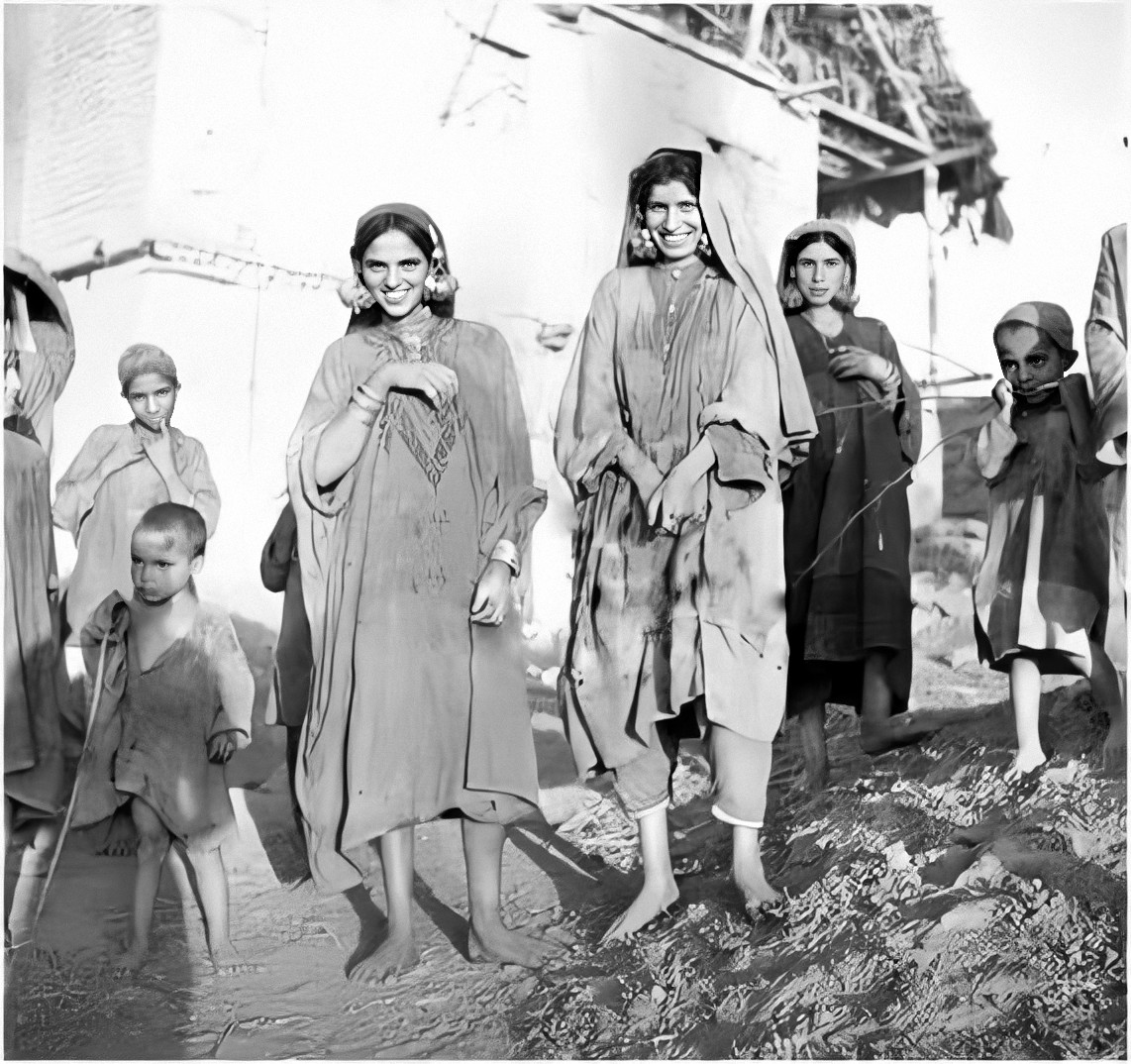

August 31th: My last day in Sreenuggur – and now let me make a few observations on a topic which I dare say you are surprised has not been mentioned before, I mean the women; the far-famed beauties of Kashmir. I am not ungallant, while I have been silent, I have been observing, and have delayed my remarks in order that they might have the benefit of the largest experience I could command. I did this the more willingly because to tell the truth, I was disappointed at first, and I hoped that by waiting I might eventually have reason to change my unfavourable opinion. This, however, has not been the case, and while I intend to do full justice to their charms I must commence by saying that they have been grossly exaggerated. I do not, of course, allude to the higher classes. They are invisible; they may be very beautiful, but are never seen by Europeans. But the middle and lower classes go about with the face uncovered, exposing themselves to the criticism of some and the admiration of others, and it is of them I speak. The slim elegant figure of the Hindoo is seldom seen; they are large, plump, round women. Their complexion has been absurdly compared to that of our brunettes (may they feel complimented thereby) but veracity compels me to say that they are very dark. Fair indeed by comparison with the Hindoos, but actually and unmistakeably copper-coloured not to say black. In their features we find a great improvement; a well-shaped nose replaces the expanded nostrils, compressed lips, the thick pouting ones, their teeth are of marvellous whiteness and regularity as are those of all Asiatics. Their cheeks may sometimes have a tinge of pink, but this is usually veiled by the darker tint of the “rete mucosum.”

Their eyes – oh! their eyes! – here lies their beauty, almond-shaped eyes, that when not in anger cannot help throwing the sweetest and most captivating glances. None of your trained disciplined eyes taught to express feelings that do not exist; but still, eyes that equally deceive, eyes that nature in some strange freak determined should ever look love.

Unconsciously and unintentionally they dart upon you the brightest, the most tender, nay, even passionate glances. When looking at a young face, you only see the eyes; eyes so voluptuous, so maddening, that you exclaim “good heavens what a beautiful creature,” and unless you are a calm and cool analyst like myself, you may not discover that there is really no beauty save in them.

They dress their hair in a peculiar manner. It is plaited in a number of small plaits joining two larger ones which fall over the shoulders and unite in the middle of the back to form a long tail terminating with a tassel. The larger plaits are mixed with wool, this adds to their bulk, and increase the length of the tail, which often extends below the knees. They wear a single loose gown, reaching in ample folds nearly to the feet. On the head a small red skull cap, over which is thrown the white (too often dirty) “chudder” – a light cloth which hangs down the back and is used for veiling the face.

The boatwomen are renowned for their beauty. I have seen but little of it. The Punditanees are said to be more beautiful than the boatwomen. I consider them even less so. But among the Nautch girls, I have seen both grace and beauty, and as a class, I certainly think far better looking than the others. Respect to age is a noble feeling – though one that is unfortunately at a low ebb nowadays – but truth, compels me and I must pronounce all the elderly women to be positively ugly, and a woman is elderly in Kashmir when in England she still might be called young.

The men are a fine race, regular features, broad-shouldered and muscular, wearing their bushy black beards on their faces, but shaving the head, which is covered with a small coloured skull cap and white turban.

Two other men have pitched their tents under this tope. Tomorrow I shall leave them in undisturbed possession of the whole. They are friends and have been travelling in Kashmir. I have had a conversation with one of them, but I don’t like strangers and am glad they did not come before.

(These passages were excerpted from Three Months of My Life: A Diary of the Late J F Foster, Assistant Surgeon, Her Majesty’s 3oth Foot. Many years after his death, the notes – written by a pencil on a notebook, were edited by Lizzie A Freeth and published in 1873. He was on a medical leave in Kashmir and on way home, he died at Malta)