by Muhammad Nadeem

The ICC has a pivotal chance to challenge the climate enabling perpetual Israeli occupation offenses. But political headwinds, resource constraints and the court’s imperfect record of accomplishment temper expectations.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is a permanent, treaty-based court located in The Hague, Netherlands that investigates and prosecutes individuals accused of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and aggression. Established in 2002 under the Rome Statute signed by 120 countries, the ICC represents the first permanent international criminal court in history, marking a major step forward in the global fight against impunity for mass atrocities.

History and Workings

The concept of an international criminal court dates back over a century, but the atrocities of World War II drove real momentum. In the aftermath, the Allied powers established the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals to prosecute Axis leaders for war crimes, crimes against humanity and waging aggressive war. These tribunals laid important legal precedents but were ad hoc in nature. Throughout the Cold War stalemate at the United Nations, efforts stalled to create a standing court. However, atrocities in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the 1990s prompted the Security Council to establish tribunals to investigate genocide and ethnic cleansing in those countries.

These temporary tribunals set additional legal precedents and built political will for a permanent international criminal court. By 1998, most UN members had signed the Rome Statute establishing the ICC. Its district would complement national criminal jurisdictions, stepping in only “where national authorities are unwilling or unable to hold genuine proceedings”. The court came into being on July 1, 2002, after ratification by 60 countries.

The Rome Statute governs the ICC and comprises four key organs: the Presidency, Judicial Divisions, Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), and Registry. The Presidency handles external relations and administrative oversight. The 18 judges are divided into Pre-Trial, Trial and Appeals Divisions to conduct proceedings. The OTP investigates situations and brings cases against individuals. The Registry handles nonjudicial operations like security, interpretation, and court management.

The ICC has jurisdiction over genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and aggression within member states when national authorities fail to act. UN Security Council referrals can also confer jurisdiction regardless of country membership. However, the ICC operates on the vital legal principle of complementarity: it only prosecutes when national legal systems cannot or will not pursue justice themselves. As an international body, cooperation from national governments is essential for making arrests, enforcing sentences, accessing crime scenes and more.

Most funding comes from member-state dues. Non-member countries like the United States have sanctioned ICC officials when proceedings involve their citizens. But the court has found meaningful success investigating atrocities in Sudan, Libya, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya and more. By early 2022, over 15 cases had reached verdicts while over 30 situations remained under examination or investigation with 11 trials underway. The ICC cannot end impunity alone but represents an imperfect, ongoing experiment in international criminal accountability.

The ICC and Palestine

One situation that continues to test the ICC is Palestine. Israeli apartheid in Palestine dates back over half a century in the contested territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Palestine was placed under British administration after World War I until the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Conflict followed the establishment of Israel and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. Israel occupied East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza in 1967 during another regional war.

Decades of tensions have boiled over into violence between Israeli forces and Palestinian armed groups. Though Palestinians have sought legal recourse through Israeli courts for individual injustices, systemic impunity reigns. Over 1,000 formal complaints against the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) from Yesh Din have yielded just 1 conviction and 7 indictments while over 300 investigations were closed. Amnesty International concluded the Israeli system “reinforces a lack of accountability for violations of international law” enabling apartheid and persecution.

Seeking accountability via external courts has also faced immense challenges. The International Court of Justice issued a non-binding 2004 advisory opinion that Israel’s separation wall and settlements in occupied territory breached international law. But no enforceable orders followed, and Israel dismissed the court’s authority. The absence of Palestinian statehood also hindered jurisdiction in international suits. So, in 2015, Palestine took a major step by acceding to the Rome Statute, accepting ICC jurisdiction for alleged crimes within its territory. The ICC recognised this jurisdictional claim pending investigation.

ICC’s Palestine Proceedings

After extensive review, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan announced in late 2021 that he had grounds to investigate possible war crimes by Israelis and Palestinians back in June 2014. But acknowledging legal complexities, Khan first sought court permission to clarify the scope of territorial jurisdiction before proceeding including Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

A five-judge panel confirmed in early 2022 that the territories in question fall under ICC purview based on membership accessions. Within weeks, the prosecutor officially launched investigations including alleged forced displacement, unjust detention, torture, and disproportionate military attacks against civilians. It marked the first such external criminal probe focused squarely on the Israeli occupation.

But Khan immediately faced criticism during a visit to the West Bank territory. Meeting with victims for just 10 minutes, he spent more time touring Israeli areas affected by Palestinian rocket attacks. Declining offers to witness settlements and checkpoints in Palestinian zones, Israel barred his travel to Gaza. It was observed Khan showed clear bias, downplaying their plight while fixating on isolated violent acts by Hamas and other resistance groups.

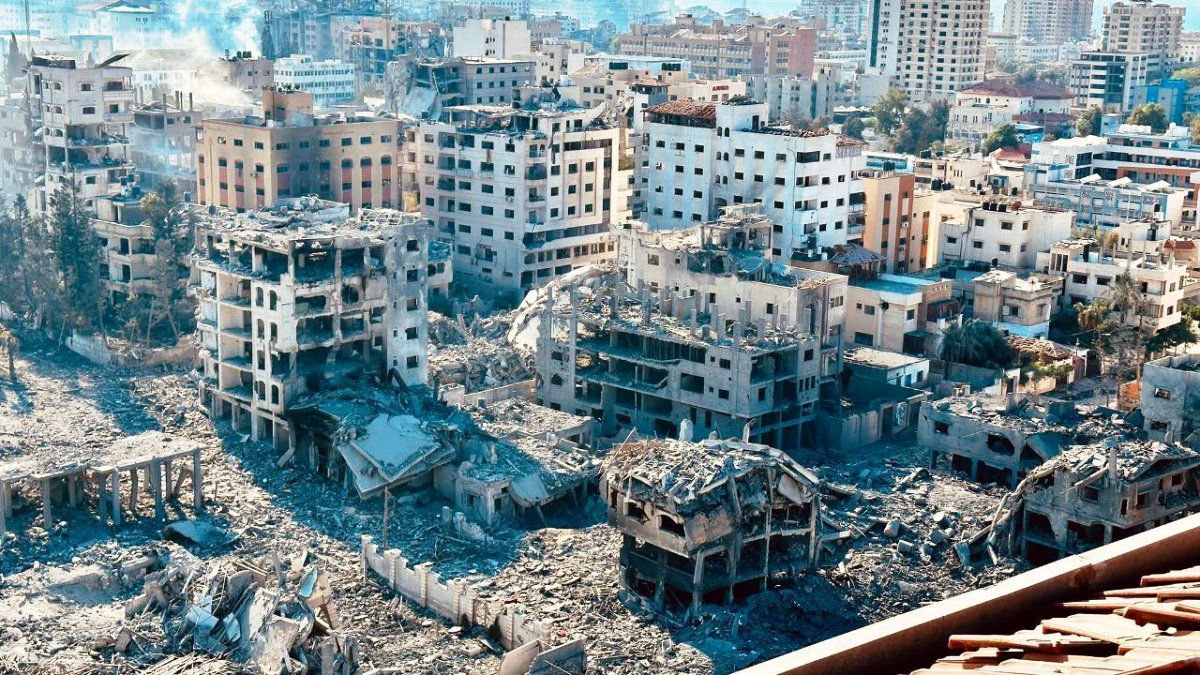

Statements from Khan’s office mostly reiterated previous calls for all parties to respect international law. Despite the extensive onward timeframe, he labelled an October 2022 Hamas barrage “serious international crimes” but only gently warned Israel over its far more devastating strikes killing hundreds of Palestinian civilians. Given Khan already deprioritised probing US forces in Afghanistan to focus on less-resourced Taliban crimes, many fear he will now chase Palestinian militant offences while leaving systemic, deadly Israeli violence largely untouched.

Addressing Genocide

The prosecutor’s visit renewed victim concerns that the ICC lacks meaningful independence and that Palestinian cries remain downgraded. But the court still represents a significant opportunity for justice external to inherently biased Israeli legal channels. Specific actions the ICC could take include pressing charges for key decision-makers overseeing policies enabling alleged war crimes and apartheid instead of lower-level scapegoats. Spotlighting crimes early in conflicts before casualties and resentment mount on both sides. Seeking asylum support from member states for witnesses facing retaliation for testifying against Israeli offences. Sustaining public statements and scrutiny calling out systemic impunity around Israel’s war crimes against Palestine state.

Conclusion

The ICC has a pivotal chance to challenge the climate enabling perpetual Israeli occupation offenses. But political headwinds, resource constraints and the court’s imperfect record of accomplishment temper expectations. Lasting justice relies on integrity and wisdom proceeding judiciously based on truth over selective agendas. The prosecutor must uphold principles of universality and impartiality by following the facts wherever they lead.