by Faizan Bhat

While Ranjitsinhji was undoubtedly a cricketing legend, his lack of involvement in Indian cricket and his alleged collaboration with the British raise serious questions about the appropriateness of naming such a prestigious tournament after him.

The recent One-Day International World Cup has captivated the attention of media, social media, and even everyday conversations. In his book History of Bodyline, Lawrence Quesne states, “Sports have been the greatest furnaces of mass popular emotion in this century.” Cricket offers more entertainment than Bollywood and other forms, captivating audiences with its inherent excitement, glamour, and suspense. The sport has even elevated cricketers to the status of film stars.

When the Indian team takes the field, work comes to a standstill, from schools to offices. Even informal discussions turn to cricket, uniting the nation. Despite its diverse landscape of castes, classes, and languages, India finds common ground through its love for the game.

In India, cricket transcends mere entertainment. It embodies national sentiment and identity. A 2007 survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, a prominent Delhi-based think tank, revealed that “eighty per cent of Indians under the age of twenty-five follow cricket,” translating to over half a billion cricket fans in the country.

For many Indians, cricket serves as a source of anxiety and depression, as well as emotional and mental strength. In his book, The Tao of Cricket, psychoanalyst, and intellectual Ashish Nandy writes, “Cricket is an Indian game accidentally invented by the English.” This statement reflects India’s deep-rooted passion for cricket, surpassing any other cricketing nation in the world. It is an undeniable national obsession.

A Colonial Game

Cricket was introduced to India by British soldiers and sailors during the British Raj. The Calcutta Cricket Club, established in the eighteenth century by officers of the East India Company, became the first cricket club founded outside of Britain.

For over a century, Indians have embraced the sport. In his book Cricket and Travel in India and America, British traveller AG Bigot observed in the early nineteenth century, “Wherever they may be, North, South, East or West, sooner or later, provided a sufficient number are gathered together, there is to be a cricket match.” Further evidence of this long-standing passion can be found in Bombay Gymkhana’s record of over 20,000 spectators attending their match against the MCC during the latter’s first tour of India in 1926.

This historical context underscores the enduring love for cricket in India. From its captivating entertainment value to its profound cultural significance, cricket continues to weave itself deeply into the fabric of Indian society.

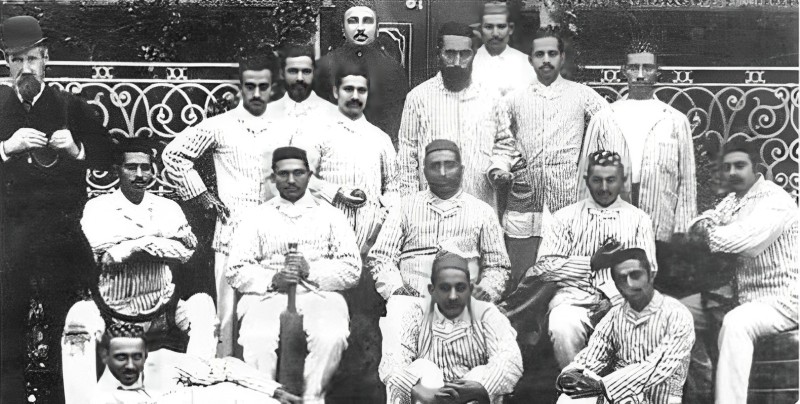

Parsis and Princes

Parsis, or Zoroastrians, were the first to embrace cricket in India. Recognising its potential for social mobility and collaboration with the British, they formed the Oriental Cricket Club in 1848, becoming the first non-British club in the country. By the 1860s, India boasted thirty Parsi clubs, largely supported by powerful families like the Wadias and Tatas. During this period, Parsi dominance in municipal politics extended across many provinces, and they strategically utilised cricket to advance their political agenda. The popularity of Parsi cricket was such that, upon meeting a Tata, President Roosevelt inquired, “How is Parsi cricket going?”

Alongside Parsis, anglicised Indian communities and feudal princes were early adopters of cricket. The sport offered them a path to social status and access to the Raj’s power elite. CLR James, in his seminal work Beyond the Boundary, eloquently demonstrates the broader political, economic, and social influence of cricket. The game instilled respect for rules, laws, and the impartial authority of umpires, which, in turn, could be interpreted as fostering obedience to colonial regulations and officials.

Inspired by Maharaja Rajindra Singhji of Patiala, other princely rulers, such as those of Bhopal, Baroda, and Holkar, enthusiastically embraced cricket. They went so far as to offer jobs to talented players. The Maharaja of Holkar, for instance, appointed India’s first cricket superstar, CK Nayadu, as a colonel in his army. Similarly, Maharaja Dhanarajgirji patronised Mushtaq Ali, and Raja of Jath supported Vijay Hazare. This princely patronage stemmed from the prestige associated with cricket and its utility as a tool for collaboration.

In 1910, following the assassination of a British official by an Indian revolutionary, Maharaja Bhupindra Singh responded by captaining and financing the All-India team’s 1911 tour of England—this gesture aimed to promote peace and collaboration with the British Raj. Notably, the Maharaja of Porbandar, despite averaging a mere 0.66, captained the Indian team in the official 1932 Test series.

The British also recognised the political potential of cricket. Former captain ES Jackson was appointed Governor of Bengal, Lord Harris served as President of the MCC, and Lord Willingdon became Viceroy of India. As Australian historian Richard Cashman writes, “Sahebs used cricket for a greater influence on colonial policymakers.” This sentiment is further echoed by Duleepsinhji, the second Indian cricketer to play for England, who remarked to a Briton that “Cricket is a way to get into the good books of Britishers and to impress them.”

The final Nawab to play for India was Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi. He made his debut before losing an eye in an accident but continued playing throughout his career with only one eye. Remarkably, he became the youngest captain to lead the Indian team and is considered one of the country’s greatest captains, having led India in numerous prestigious tournaments. His father, Nawab Iftikhar Ali Pataudi, played for both England and India, captaining the Indian team in 1946.

The Institution of Cricket

The British left behind a legacy of institutions including the army, civil services, and cricket, which have become ingrained in India’s socio-political and cultural fabric. Ironically, the team and game that once defined the identity of the colonisers is now deeply revered by the nation they conquered. Cricket in India is a multi-billion-dollar industry, infused with celebrity culture and highly politicised. It forms an integral part of the nation’s public consciousness, with victories celebrated as national triumphs and losses mourned collectively.

This profound influence is exemplified by the recent meeting between UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Indian Foreign Minister S Jaishankar during Diwali. Jaishankar’s gift to Sunak – a statue of Lord Ganesha and a cricket bat signed by Virat Kohli – underscores the immense cultural and political significance of cricket in India.

As Ashish Nandy states in his book, “Some arguments about colonial, neo-colonial, anti-colonial and post-colonial consciousness can be better made in the language of international cricket than that of political economy.” This statement holds weight when considering the legacy of Ranjitsinhji, the first Indian to play cricket at the international level.

Ranjitsinhji was educated at Rajkumar College, which espoused the philosophy of real cricket as a tool for education. By the age of sixteen, his cricketing skills had earned him a place at the University of Cambridge, where he won the Cambridge Blue. He went on to play for England in fifteen tests between 1896 and 1902.

Ranjitsinhji’s cricketing achievements were remarkable. He was the first to score a century before lunch, the first to score centuries on both his home and overseas debuts, the first to score three thousand runs in an English season, and the only cricketer to score two centuries in two innings on the same day. His batting prowess earned him widespread praise from cricket greats like John Lord, N Cardus, and Dr WG Grace.

However, Ranjitsinhji’s legacy is a complex one. He has been criticised for collaborating with the British and for never considering himself an Indian cricketer. He refused to captain the All-India tour to England in 1911 and even discouraged his nephew, Duleep Singhji, from playing in the 1932 Test series. Despite his immense cricketing talent, he never actively contributed to the development of cricket in India.

This raises the question: why is the Ranji Trophy, India’s premier domestic cricket tournament, named after a figure with such a controversial legacy? While Ranjitsinhji was undoubtedly a cricketing legend, his lack of involvement in Indian cricket and his alleged collaboration with the British raise serious questions about the appropriateness of naming such a prestigious tournament after him.

Ranjitsinhji Versus Palwankar Baloo

In stark contrast to Ranjitsinhji stands the forgotten figure of Palwankar Baloo, India’s first great cricketer. Baloo, the son of an army man, faced discrimination throughout his career due to his caste. Despite this, he shone on the field, becoming the star bowler of the 1911 All-India tour. He was hailed as a hero by Dalit leader Dr BR Ambedkar and compared to iconic figures like Jackie Robinson and Mohammad Ali by historian Ramchandra Guha.

Sadly, Baloo’s contributions have been largely ignored by the cricketing establishment, a stark reminder of the casteism that continues to plague Indian cricket and society at large.

Another example of caste bias in Indian cricket is the case of Vinod Kambli. Childhood friend and partner of legendary cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, Kambli was considered by their coach to be the more naturally talented batsman. Both broke the record for the highest partnership in the Harris Shield school tournament, but their careers diverged sharply. Tendulkar, an upper-caste cricketer, rose to superstardom, while Kambli, a lower-caste fisherman, was dropped after a disappointing series against the West Indies. Kambli himself has attributed his downfall to caste and colour discrimination.

The stories of Baloo and Kambli highlight the complex relationship between cricket, caste, and politics in India. While the sport has brought immense joy and pride to the nation, it continues to grapple with issues of social inequality and discrimination. It remains to be seen whether the cricketing establishment will acknowledge these issues and take steps towards creating a more inclusive and equitable sport.

Richest In India

Cricket has transcended its British origins to become a global phenomenon played and loved by 104 countries. Today, India is its richest and most powerful member, wielding significant influence within the International Cricket Council.

In the late 1940s, as India approached independence, the future of cricket within the new nation was uncertain. In 1946, the All India Congress Committee Secretary expressed scepticism, stating, “Cricket has hardly any future in India. It is purely English in culture and spirit. With the fall of British power, it will lose its place of honour and slowly die.”

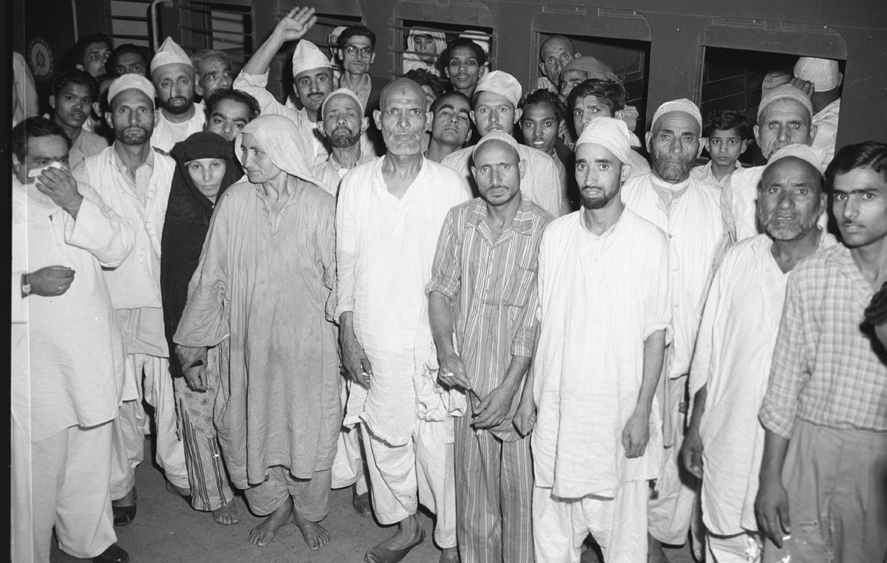

However, cricket defied these predictions and persisted alongside other symbols of British rule. In 1954, Vice President Radhakrishnan inaugurated the India-Pakistan Test match, sending a powerful message. Although the Pakistani media framed the tournament as a symbolic struggle for “Kashmir”, cricket continued to be embraced by the newly independent nation.

Richard Cashman, in his book Patrons, Businessmen and Bankers, highlights the elitist nature of early Indian cricket, noting that “most of the players were upper middle class and upper caste.” However, the landscape has shifted, with more players from diverse backgrounds participating in the sport.

The advent of satellite television, global media coverage, and massive business patronage has transformed cricket into a multi-billion-dollar industry, especially in India. The Indian Premier League (IPL) has played a pivotal role in this transformation, solidifying the country’s position as a major capitalist force in the cricketing world.

Cricket generates significant revenue through advertising, broadcasting rights, and merchandise sales. The 1984-85 England tour of India exemplifies the sport’s commercial reach, culminating in the release of a commemorative book titled Olympic. This incident underscores the immense influence of cricket in Indian society.

Beyond its financial impact, cricket is also deeply intertwined with fame and celebrity status. Players are often considered national heroes and enjoy widespread recognition.

The Challenges

Despite its popularity, cricket in India is not without its challenges. Political interference is a recurring issue, with accusations of communalism and bias within cricket associations. Former Indian player Wasim Jaffer and Uttarakhand Ranji players resigned due to perceived bias by selectors. In a separate incident, former BCCI vice president and CAU secretary Mahim Verma accused Jaffer of communalism while facing allegations of sexual harassment and extortion himself.

The presence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the Narendra Modi stadium during the fourth Test match of the Border-Gavaskar series further blurred the lines between sport and politics, resembling a political rally. This event, along with the “Namaste Trump” rally held in October 2020, highlights the increasing politicisation of cricket in India.

Neeraj Kumar, former Delhi commissioner and head of the Anti-Corruption Unit of the BCCI, paints a bleak picture of the organisation in his book A Cop in Cricket. He describes the BCCI as “an organised crime from a law enforcement view”, raising serious concerns about corruption within the cricketing establishment.

Soumya Bhattacharya, in his book You Must Like Cricket, captures the essence of cricket in India. He eloquently states, “The manner in which India has made cricket its own – in terms of money it generates, the frenzy it generates and its intricacies into every area of public life, from pop culture to politics – is a marker of the post-colonial present.” While cricket may still bear the mark of its imperial past, it has undeniably become a deeply ingrained part of the Indian identity.

(The author is a columnist based in Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir)