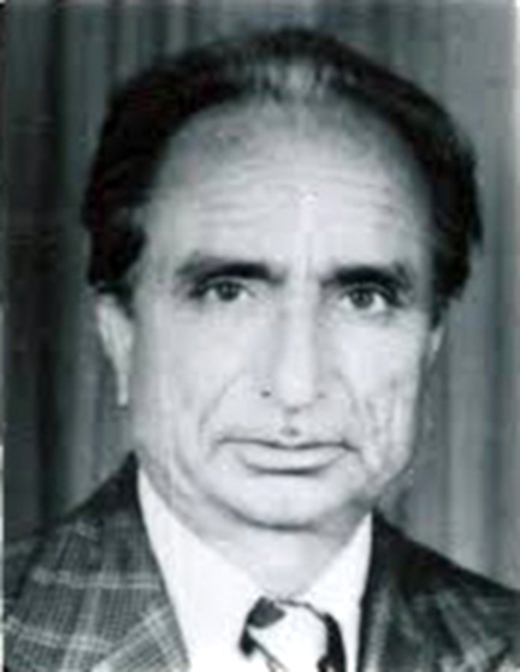

It was Maqbool Bhat’s hanging that stirred noted short story writer Akhtar Mohi-ud-din, and made him return his Literary Award. Bilal Handoo reports how turmoil and suffering of Kashmiris shaped his work

It was early eighties. And the public discourse was: Maqbool Bhat—incarcerated in New Delhi’s Tihar jail, might be hanged very soon! This had triggered many campaigns in valley to press upon India not to hang him. One of the prominent faces—leading from the front, was the renowned Kashmiri short story writer, Akhtar Mohi-ud-Din.

Akhtar had issued statements in local dailies, urging the government of India not to hang Maqbool. “Gaandhi Ji’s India will not gain anything by hanging Maqbool Bhat,” one of his statements read. But his pleas fell on deaf ears. Bhat was hanged. And in protest against hanging, Akhtar returned his literary award given purely for the literary merit of his works.

Akhtar who considered Maqbool Bhat as the “National hero of Kashmir” was hailed for his courageous act to return the honour. Soon after Bhat’s hanging, Akhtar in his correspondence to then Indian prime minister expressed his strong resentment and hurtful feelings over the act.

He was one of the few local writers who identified himself with the political struggle in Kashmir. As a short story writer, he reflected the turmoil which gripped valley in 1990s. His collections of short stories published posthumously reveal a mind constantly grappling with violent transformations in Kashmiri society.

He gave vent to his feelings for Kashmiris in his verses and pieces of fiction. In his book ‘Seven One Nine Seven Nine,’ Akhtar depicts the plight of Kashmiris in a piece of fiction titled Jali huend dande phol. His write-up Aatak Wadi conveyed that ‘Indian soldiers looked at Kashmiris as nothing but terrorists’. He was a first Kashmiri writer to dedicate his novel Jahnamuk Panun Panun Naar in 1975 to the person “who would fire the first bullet to set things rights in Kashmir”.

During the nineties when the graph of human rights violations escalated in valley, Akhtar in protest returned Padma Shree award given to him in 1968.

He wrote to different ministers besides the home minister about the atrocities that government forces were committing in the valley during 90s, says Azar Hilal, his son.

“He urged ministers to put a check on the excesses of security forces in Kashmir,” says Hilal. “But when there was no response to his repeated pleas, he thought the only weapon in his hand was to return the award he got in the literary field.” This was his way of showing solidarity with his people.

And meanwhile, he continued to be the part of people’s movement. In early 1990s, he joined Hurriyat Conference. For a known socialist like Akhtar, this was a difficult intellectual journey.

“I feel a writer cannot go without politics,” Akhtar once wrote, “but he cannot converge himself into the channel of party politics.” A writer, he said, must associate himself with the large majority of the people: “Therein dwells the real life and real experience.”

Born on April 17, 1928 in Srinagar, Akhtar is considered to be a trend-setter among the Kashmiri prose writers. He has written more than forty radio plays and six collections of short stories. He has also published two novels, Daud Dag (Disease and Pain) and Zuv ti Zulan (Precarious Life).

“His stories carry the feel and throb of the living style of ordinary people in Kashmiri society,” writes Autar Mota, a blogger. “Read him in original Kashmiri or translations, he leaves an impression.”

Akhtar laid down the strong foundation of modern Kashmiri literature. He was one of the founder members of Progressive Writers’ Association in 1950s. And also, he was the first Kashmiri who was awarded the Sahithi Academy Award for fiction in 1956.

In his personal life, however, Akhtar kept struggling. During turbulent nineties, some unknown gunmen killed his son. And later, his son-in-law was killed by CRPF. But he refused to succumb to loss. He put up a brave face and kept his son-in-law’s three little daughters at his own home. He became their guardian and gave them protection.

But at the age of 74 (on May 2, 2001), Akhtar lost the battle of his life. He was suffering from an intestinal malignancy.

In 2007, the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), a Srinagar-based civil rights group, posthumously conferred Akhtar with Robert Thorpe award.

“Akhtar was a courageous person who resisted all acts of injustice, slavery or any unlawful activities happening during his time,” says Zareef Ahmad Zareef, noted poet and critic. “He always stood for justice and asked for an end to human rights violations.”

There was intellectual honesty in him, believes Dr Altaf Hussain, noted paediatrician and writer: “He kindled the spark of freedom struggle in Kashmir, which then hit martyrs like Maqbool Bhat, and Ishfaq Majeed etc.”