In Kashmir, the prestigious Aligarh Muslim University is linked to two towering personalities, both named Sheikh Abdullah. While one, almost every Kashmiri is aware of, the other Sheikh Abdullah is hardly known despite his immense contribution to the Muslim women of India, reports Saima Bhat

In the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) Abdullah Hall, is the most sought after place for female undergraduates. A universe in itself, it has everything that more than 3000 inmates require to feel homely. Comprising nine girls hostels, it has two canteens, a gymnasium, a basketball court, an auditorium, a well-equipped computer, and a reading room, besides all the essential shops. Within this space, students have an independent private life.

Behind the solace of these young girls in Abdullah Hall is a struggle of a man known as Sheikh Abdullah. He fought fiercely to ensure a place for girl education and is considered to be the pioneer of female education in male-dominated British India.

Sheikh Abdullah

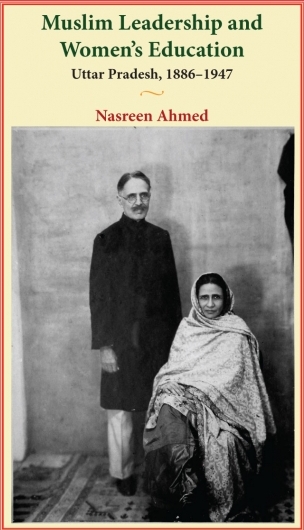

A reverted Muslim, Sheikh Abdullah was born on June 21, 1874, as Thakur Das in a Kashmiri Brahmin family in Poonch. Dr Nasreen Ahmad, in her Muslim Leadership and Women’s Education Uttar Pradesh, 1886–1947, suggests that Sheikh was born in Bhantani village, where his paternal grandfather, Mehta Mastram was a Lambardar (Village Headman).

“Thakur Dass was a Kashmiri Brahmin whose father had embraced Sikhism,” writes Avtar Mota in his blog Chinar Shade. “The ancestors of Thakur Dass had moved out from Kashmir and shifted to Poonch during the Pathan rule or even earlier.” He believes Das’s grandfather was a landlord.

Not knowing much about his ancestors, however, Dr Nasreen writes that Das’s early education started with Persian, after which he attended a Maktab in Poonch. Every day, he would trek 5 miles to learn Sanskrit and Persian.

While being in school, he attracted the attention of Hakim Numddin, the court physician to then Maharaja of Kashmir, who had come to Poonch to treat a member of the royal family. Poonch rulers were cousins of Kashmir Maharaja.

The Hakim offered his family that he would train him in Unani medicine in Jammu, to which the family reluctantly agreed.

Hakim Numddin, Dr Nasreen writes was a leading Qadiani of his times and under his influence, Thakur Das converted to the Ahmadiya sect after which he was named Sheikh Abdullah.

As young Sheikh moved to Lahore for secondary education, he attended the convention of the Mohammedan Educational Conference. There, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s speech impressed him.

After qualifying his tenth class in 1891, Sheikh went to Aligarh with a letter of introduction from his mentor Hakim to Sir Syed Khan. Subsequently, he was admitted to the first year in law school. Dr Nasreen writes that it was in Aligarh where Sheikh renounced Ahamadiya faith and became a Sunni Muslim.

While in college, Sheikh’s interactions with Sir Syed inspired him to write and get into community service. “Sir Syed used to entrust the boys with responsibility; the names of Aftab Ahmad Khan and Sheikh Abdullah figured at the top. Because the latter in a way spiritually identified with the Movement, he was appointed as a librarian,” Writes Dr Nasreen.

After completing LLB, Principal Beck who was also the Secretary of the Movement suggested that he should set up practice in Aligarh. “He accepted, stayed on, and became active in the Old Boy’s Association.” He was a member of the university court from 1920 till his death.

In Aligarh, Sheikh found a new home and family. He became a member of the Duty Society, a select group of Aligarh students founded by his friend, Aftab Ahmad Khan, to raise funds for the college. Eventually, a north Indian ashraf adopted him. Soon he was married.

AMU- The Idea

Post-1857 mutiny, reformer Sir Syed Ahmad Khan felt the need to involve Muslims in the governance structure and other affairs of public importance. It was an indirect outcome of the British India government decision in 1842 to replace the Persian by English as the court language. It was almost a denial to Muslims to be in government.

Sir Syed wanted Muslims to acquire proficiency in the English language and Western sciences if they wanted to maintain their social and political clout, particularly in Northern India. He began to prepare a foundation for the formation of a Muslim University by starting schools at Moradabad (1858) and Ghazipur (1863). His purpose for the establishment of the Scientific Society in 1864, in Aligarh, was to translate Western works into Indian languages as a prelude to prepare the community to accept Western education and to inculcate scientific temperament among the Muslims.

In 1877, Sir Syed founded the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligarh on Oxford and Cambridge pattern after his trip to England. His objective was to build a college in tune with the British education system without compromising its Islamic values.

The college was originally affiliated with the University of Calcutta and subsequently got affiliated with the University of Allahabad in 1885. Near the turn of the century, the college began publishing its magazine, The Aligarian and established a Law School. By then, a movement for upgrading it into a university.

Demand, Deliverance

After the college was established, Dr Nasreen writes, northern India was witnessing a phase of reforms. Taking a cue, Muslim reformers were also advocating for female education but with a condition of purdah. Few thought that purdah should not act as a barrier. They included Syed Mumtaz Ali, Nazir Ahmad, and the Nawab of Bhopal, Begum Sultan Jahan. Ashraf Ali Thanwi in Bihishti Zewar, Nazir Ahmad in Mirat ul Tjrus, and Altaf Hussain Hali in Majalis un Nisa, strongly advocated female education.

The newspapers also supported female education. The first women’s Urdu magazine Akhbar-un-Nisa of Syed Ahmad Dehelvi also supported the idea. Those supporting it, Dr Nasreen argues were seeking basics of religion, reading and writing skill, elementary mathematics, and basics of household management to be taught to women.

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s publications Tahzib ul Akhlaq and Aligarh Institute Gazette also supported female education after the 1880s but within “limits” as Muslim intellectual believed that if women are educated they will become “irresponsible”.

“In his testimony before the Indian Education Commission of 1882, Sir Syed maintained that a little education was enough for women. Until more Muslim men received a sound education, Muslim women would have to wait: The present state of education among Muhammadan females is, in my opinion, enough for domestic happiness,” writes Dr Nasreen. But Hali disagreed, wrote a counter and started a couple of schools for girls in his home town of Panipat, which were run by the women of his family.

Sheikh Abdullah thought differently. It is believed that Hali’s poem Chup ki Dad in praise of Muslim women was, written on Sheikh’s request. It was first published by Sheikh in his Urdu journal for women, Khatun in December 1905. “In it, Hali reiterates many of the ideas he had originally espoused in his Majalis un Nisa: Women are the true strength of the family and the community, but lamentably many of them are kept in ignorance; thus women’s education is vital for the regeneration of the Muslim community,” Dr Nasreen writes.

By 1880, Sir Syed had rejected the idea of a school mooted by the government. His argument was: “It was not possible for Government to adopt any practical measure by which the ‘respectable Mohammadans’ may be induced to send their daughters to Government schools for education. Nor, he claimed, could Government bring into existence a school on which the parents and guardians of girls may place perfect reliance.”

Sir Syed’s opposition to modem education to women was his belief that they should stick to the traditional system of education as it helps them in their moral and material wellbeing and protects from difficulties. He believed educating boys would automatically improve the condition of men and women.

This all, however, did not impact the strong movement for the female education that started after 1888. In the Third Annual Conference of the Mohammadan Educational Conference held at Lahore, a resolution said: “The Mohammadan Educational Conference unanimously agrees to the proposal that Muslims should establish schools for the education of Muslim girls. These schools should be in accord with Islam and of the ways of the Sharif section of the Muslims.” It was passed despite Sir Syed’s opposition. MAO College Principal, Dr Nasreen quotes Sheikh saying that Sir Syed went even to the extent of believing that the girls studying in schools and colleges would become “immoral”.

Theodore Beck, who had grown hugely influential within and outside the college, threw his weight behind the movement.

Sir Syed started mellowing down. On November 15, 1884, Beck chaired a debate on the issue at Siddon’s Union Club. The motion over which the debate took place was cleverly worded, apparently taking the Sir Syed line: “Spread of female education in India is to be desired but by home tuition and not by schools and colleges.” It was defeated by a narrow margin of three votes.

Sir Syed never opposed female education ferociously and never supported the idea clearly. The movement for Muslim female education did start in his but intensified only after his death in 1989.

In 1891, a resolution was proposed by Moulvie Syed Karamat Hussain. In 1896, for the first time, a special 6-member Female Education’ Section in the Mohammadan Anglo-Oriental Educational Conference was created. They all were sympathetic but hugely conservative. In subsequent years, Moulvie Mumtaz Ali, one of the members, opposed Sheikh Abdullah’s efforts to establish a girl’s school at Aligarh. Mohsin-ul-Mulk, another member, refrained from openly supporting the endeavour. Mohsin-ul-Mulk, yet another member, prevented Sheikh from presenting a resolution for the establishment of a girl’s school at Aligarh in the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental Educational Conference in 1904. Much earlier, Sheikh had been denied a berth in the panel along with Ghulam-us-Saqlain.

From Begum Abdullah’s biography, Dr Nasreen writes that in 1902 Shiekh was elected as the member and secretary of the Female Education Section. It was the same year he had married Waheed Jahan, from an old Mughal family of Delhi in which women’s education was a tradition. Her father Ibrahim Mirza, had taught his daughters Persian and Urdu and had also permitted an English woman to teach them. Together, the Sheikh and Begum Abdullah began a campaign to open a girls’ school in Aligarh.

In 1906, the couple founded Aligarh Girl’s School in the midst of opposition but support from Nawab Sultan Jahan Begam, the ruler of Bhopal –a grant of Rs 17,000 with an additional monthly allowance of Rs 250. That was a promising start and there was no looking back.

Girl’s School

The idea of starting a school for Muslim girls took shape in 1903 in Bombay during the Muhammadan Anglo-oriental Educational Conference. But the place could not be decided.

After the conference was over, Sheikh contacted Maulana Mumtaz Ali, Editor, Tehzeeb Niswan (Lahore) and Mehboob Alam, Editor, Paisa Akhbar, (Lahore) to establish a normal school at Lahore. But both of them responded negatively and Sheikh took it upon himself the stupendous task of establishing a school for Muslim girls in Aligarh.

To know the public response, he asked his wife to call a conference of educated ladies in her house to discuss the problem of Muslim female education. When ladies gathered, prominent among them were Mrs Razaullah Khan and Sayeed Ahmad Begum, all of them were in favour of female education. It triggered a lot of criticism locally with their detractors saying that methods of the English were going to be practised and schools would be opened for girls who would attend it without observing purdah. The other allegation was that in the proposed school, ‘good’ and ‘bad’ girls would meet which would be detrimental to the interests of girls coming from good and decent families.’ Moreover, fears were also expressed whether such a school would succeed in giving proper training in ‘Islamic culture and decency’.

But it did not impact the missionary zeal of Abdullahs’. Instead of being discouraged, in 1904, Sheikh took a bold step and started a magazine entitled Khatun for mobilizing public opinion in support of women’s education and in the general welfare of women. He was supported in this effort by Saiyid Sajjad Haider, Syed Abu Mohammad, Moulvi Ehteshamuddin and Moulvi Enamul Haq. The first issue of Khatun came out in July 1904 and it created a furore in Urdu journalistic circles. Other magazines and newspapers started opposing its publications by saying that Khatun was a naturi magazine and was being published with the aim of abolishing purdah.

The hostile propaganda against Khatun alarmed Mohsin-ul-Mulk, who was then Secretary of the Board of Trustees, MAO College. He advised its publication be stopped. Sheikh convinced him to write for it, instead. The publication continued till 1914.

Finally, the resolution to establish a girls’ school at Aligarh was unanimously approved in the All India Muslim Ladies Conference held in Aligarh in December 1905. The leaders of the Aligarh Movement initially were not supportive. Mohsin-ul-Mulk refused permission at the last moment to use any building of the MAO College to hold the Muslim Ladies Conference and the exhibition of women’s handicrafts.

The Struggle

As Abdullahs’ hard work started bearing fruits, around 50 girl students were enrolled in the school in the first three months. He informed the then Lt Governor about the progress and Miss Ganja was asked to inspect so that she could assess the situation and report to the authorities.

Reportedly when she saw the dedication and involvement of Begum Abdullah and her sisters, she was impressed and said that they were doing the kind of work that is usually associated with missionaries. Within a month after the receipt of Miss Ganja’s report, Sheikh received a sealed envelope from the government, which contained a grant of Rs 250 per month and Rs 17, 000 for the infrastructure.

On October 25, 1906, Sheikh started the school in a small house in Mohalla Bala-e-Quila of Aligarh town after some alterations were done to ensure seclusion. Once the school premise was ready, another struggle started to get qualified teachers. So Begum Abdullah together with her two sisters had to take the responsibility of a major part of the teaching at the school.

To ensure the safety of girl students, Dr Nasreen writes that at least four men were employed to take the girls in two carefully covered dolis to their homes and bring them to the school. One female peon was also employed. The curriculum included Urdu reading and writing, basic arithmetic, needlework, and the Quran. The school building itself was walled on all sides so that purdah could be properly observed. Many times the school, students, or the staff of the school were attacked by the opponents of women’s education.

Soon after this school, on November 7, 1911, the foundation stone of the first girl’s hostel was laid in presence of Lady Porter, wife of the acting Lt Governor of the United Province. The construction was completed in 1913. Later on, the Begum of Bhopal inaugurated new buildings. It became the first Women College in Aligarh. In 1937, the Aligarh Women’s College became a part of the Aligarh Muslim University.

To ensure all security to the school and then college, Abdullah Begum became herself the warden of the hostel and all outside works were done by Sheikh himself. They were so involved personally with these girls that those girl students started called Begum as Ala Bi and Sheikh Abdullah as Papa Mian.

In 1949, when Maulana Abul Kalam Azad visited Aligarh for the annual Convocation, he was highly impressed by the role being played by Women’s College for the spread of modern education among girls. He announced an annual grant of Rs 900 thousand for the college.

The high school was established in 1921 and later gained the status of an Intermediate College in 1922. With time, in 1937 it was elevated to the status of an undergraduate college as part of the Aligarh Muslim University. Many literary figures were among the early alumni of this college.

A staunch believer in Hindu Muslim unity, Sheikh stayed back in India after the partition. He also served as a member of the United Province Legislative Council. He was conferred with the title of Khan Bahadur in 1935 and a Padma Bhushan was awarded to him in 1964. After taking the degrees of BA, LLB, AMU awarded him the degree of LLD in 1950.

At AMU, Abdullah Hall has also instituted annual Papa Mian Awards for girls who excel in academics. In 1975, Films Division, Government of India made a documentary on Papa Mian and his contribution towards women education in India. It was directed by Khawaja Ahmad Abbas.

After the death of Sheikh in 1965, the struggle for the college continues. It was only in 2014, that the students from the Women’s College stepped into the university’s central library, Maulana Azad Library. They had been barred from accessing the library since 1960, owing to “infrastructure issue”. AMU’s girls’ hostels that permitted only one-day outings for women now allow women to go out thrice a week. In March 2019, the Women’s College hosted its first-ever Women Leadership Summit. The institution now has a women’s field hockey team.

But there have been many instances when the students of this college voiced their concern against the strict rules where there are 107 teaching and 75 non-teaching staff members.

With his almost entire life spent in Aligarh, Sheikh Abdullah lies buried at the same place, he once lived, loved, and lauded.