Though accessible to people in England, the Government of India continues to restrict access to a set of documents, the Bucher Papers that have a lot of insights into the Kashmir war in 1947 and maybe the politics of that era as well

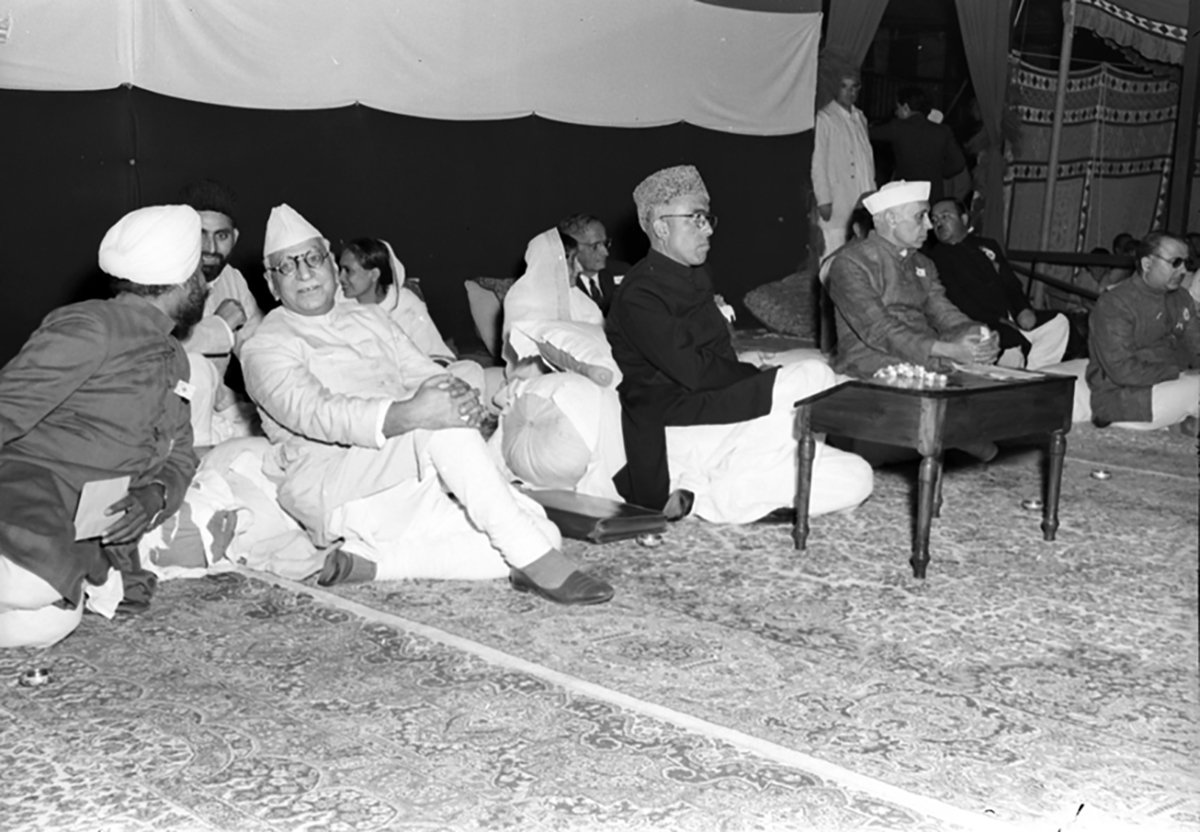

A controversy is raging over an estimated 49-document file that the Government of India is not making accessible to researchers. These are official communications between India’s second and the last non-native Chief of Army Staff, General Sir Francis Robert Roy Bucher and Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru. These especially pertain to the ceasefire between India and Pakistan on July 27, 1949, after the rival armies of the sister nations fought their first war over Kashmir in October 1947. The agreement was signed in Karachi and signatories included Lt Gen SM Shrinagesh (India), Maj Gen WJ Cawthorn (Pakistan) and Hernando Samper and M Delvoie (UNCIP).

Normally, the Government of India declassifies archival documents after 25 years. However, when academics started seeking access to, what is now being called Bucher Papers, they were told that the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) has kept the documents classified in the national interest. These documents are with the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, a Culture Ministry-run autonomous body.

This has triggered a new controversy. Nobody knows if the contents of these documents would paint independent India’s first Prime Minister in poor light or help justify his actions.

The revelations, if any, can have “significant political ramifications” and may emerge as an issue in the forthcoming Lok Sabha elections. The ruling BJP has maintained that “blunders” by Nehru led to the creation of the Kashmir issue that dominated for more than 70 years till the rightwing party scrapped the special status of Jammu and Kashmir and integrated it with the country in August 2019.

Contents of Letters

Titbits’ of the classified documents accessed by certain reporters and academics indicate it includes a communication that Bucher wrote to Prime Minister on November 28, 1948, that explained why a ceasefire was required.

“Army personnel evince two weaknesses, lack of training in the junior leaders, tiredness and ennui in the other ranks … In brief, the army needs respite for leave, training, and vitalising,” the communication said.

“Nehru, in response, raised concerns over reports that Pakistan intended within weeks to bomb Indian positions from the sky. Meanwhile, Pakistan was building roads to maintain and advance its positions,” British newspaper, The Guardian reported. It mentions Nehru’s December 23, 1948, letter to Bucher saying, “It is clear to me that we cannot rely on Pakistan remaining on the defensive…In the event of Pakistan continuing their persistent shelling and offensive operation and our not being able to check this there, there is every likelihood of war taking place with Pakistan.”

“I am afraid we cannot take military action to stop every road-building operation by Pakistan,” Bucher wrote back to Nehru on December 28. “May I suggest a political approach to this problem?”

It was only after the series of communication amid the war that a ceasefire agreement was signed at Karachi. In its immediate follow-up, Article 370 was included in the constitution, a status undone on August 5, 2019.

Off late, BJP has been dubbing it Nehru’s “biggest mistake”, with Home Minister Amit Shah asking in 2019: “What was the need to announce a ceasefire when we were about to win the war?” A month after reading down Article 370, he said: “In 1948, India went to United Nations. That was a Himalayan blunder. It was more than a Himalayan blunder.”

Colonial Masters

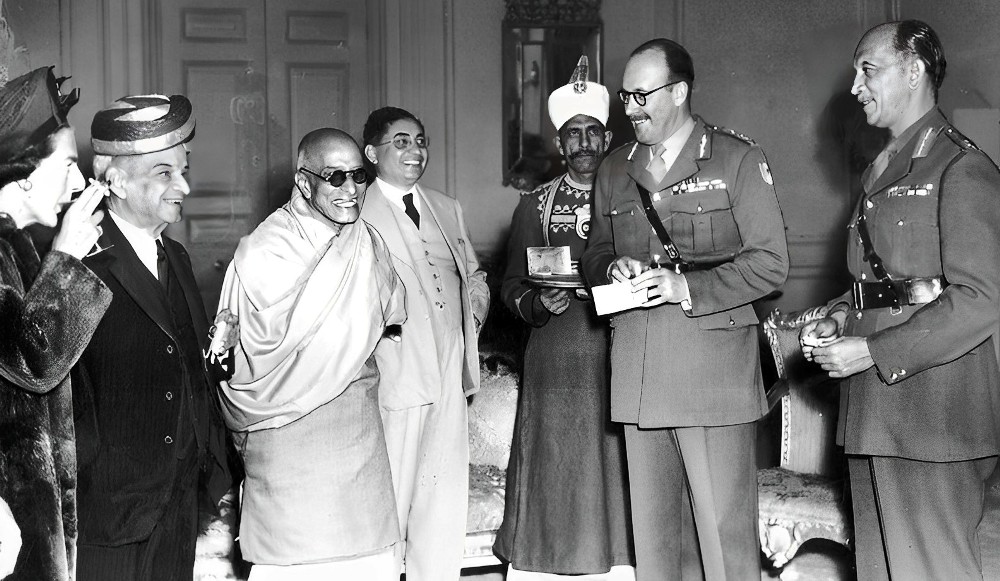

At the time of the independence of India and Pakistan, two British army officers were the chiefs of the respective armies. Even though they were two separate countries born out of mutual animosities and distrust, two soldiers from their colonial past were holding their key asset, the army. They both operated under the Joint Supreme Commander, Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, also a British.

The Pakistan army was commanded by General Sir Douglas David Gracey. He was Pakistan’s second Chief of Army. Though in October 1947, he was not the army chief, he was in command in absence of his chief. He retired in April 1951 and died on June 5, 1964.

In India, Bucher took over in 1948, replacing General Sir Robert McGregor Macdonald Lockhart, after superseding two seniors. He retired on January 15, 1949, paving way for KM Cariappa to become India’s first Indian Army Chief. It was during his two India visits in the 1960s and 1970s that he handed over the documents to the Nehru Museum. He died on January 5, 1980.

New Details

The files, the reportage of the controversy suggest, hold the answer about whether Nehru acted on his own or he acted on the advice of his army chief. Many believe these documents contain insights into the Instrument of Accession, signed on October 26, 1947, by Maharaja Hari Singh.

The first war over Kashmir is well documented. Still, a lot of academicians and scholars believe that Bucher’s papers contain a lot of information beyond that. “Roy Bucher suggested a political approach to solve the escalating situation given military fatigue faced by Indian troops due to 13 months of military deployment, including taking the matter before the United Nations,” The Guardian said in an earlier report. “That advice may have influenced Nehru’s decision to grant Kashmir special status.”

The details of the documents in the public domain suggest that Nehru did not wait for the United National Commission to suggest a ceasefire. Instead, he initiated it well before its arrival.

“I do not know what the United Nations are going to propose. They may propose a ceasefire and what the conditions are going to be, I do not know,” the papers suggest Nehru writing in one of his communications to Bucher in 1948. “If there isn’t going to be a ceasefire, then it seems to me that we may be faced with an advance into Pakistan and for that we must be prepared.”

Interestingly, Bucher, during one of his post-retirement visits to India, talked at length to biographer BR Nanda. The Bucher papers include a 20-page transcript of the interview and researchers can copy a fifth of this – not more than four pages. The interview is very important.

“He (Nehru) had become very perturbed about the shelling of Akhnur and the Beripattan Bridge by Pakistan heavy artillery from just within Pakistan; he enjoined me to do all I could to counteract this,” Bucher had told Nanda in an undated interview. “There was nothing which one could do except counter-shell.”

He told Nanda that the documents he had handed over to the Museum “portray his (Nehru’s) great grasp of the military situation in Kashmir and especially how this was influenced by the presence of the UN Commission for Jammu and Kashmir.”

On ceasefire, Bucher detailed the drama when he got a phone call from Sardar Baldev Singh suggested him to ‘go ahead’. “Well it is a jolly difficult job for me as a Commander-in-Chief to tackle and you have the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan in the country,” Bucher responded and later followed up by drafting out a “purposefully short” signal to General Gracey, his Pakistani counterpart, merely stating that “my Government was of the opinion that senseless moves and counter-moves with loss of life and everything else were achieving nothing in Kashmir.” It was sent across only after Nehru read it thrice, signed it and retained his own copy. India ceased fire at the midnight on December 31, 1948.

“The United Nations Commission was apprised of this, a day or two later; they were told that what they come out for had been achieved two days or so ago,” Bucher said. “I do not think the Commission knew anything about the cease-fire signal before that.”

Held In Secret

Why the Modi government is unwilling to declassify the documents is not known. The Guardian report said the incumbent government describes the cache of documents as sensitive. “It said the papers broadly examined the “state preparedness of Indian armed forces stationed in Kashmir, in the backdrop of the India-Pakistan war (1947-48)”, the report said, and “concerns expressed by Nehru regarding offensive military actions undertaken by Pakistan”.

Interestingly, the same set of papers is also maintained at the National Army Museum in Chelsea, London, where they are accessible to all. Nobody, however, is in a position to say if the documents at the two places are the same.

There have been attempts by various people to access these documents. Every time, however, the access was denied. Venkatesh Nayak has been engaged in a perpetual battle with officials since 2019, for the declassification of these documents. In October 2021, the Central Information Commission stopped short of ordering the disclosure of these crucial documents. Instead, it asked the Museum “to take up the matter with higher officials” and “secure the necessary permission” before sharing the information with RTI activist Venkatesh Nayak.

Even the museum authorities have put their weight in support of declassifying these documents. On October 12, 2022, the museum and library top official, Nripendra Misra, is reported to have written to India’s foreign secretary, suggesting the papers may be made accessible to researchers. “We have read the contents of the Bucher papers,” he has written. “Our view is that the papers need not remain “classified” beyond the reach of academicians.”

Full access to the papers may help settle a controversy in Jammu and Kashmir as well. It is being said publicly in Srinagar that the ceasefire took place at the behest of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah who did not want the army to go beyond Uri. The reason, for the unsubstantiated presumption, is that since he had no huge following among non-Kashmiri-speaking people, he thought they will rebel against him. Whether or not is this correct, only access to these documents will settle this regional controversy. Or maybe it might emerge another angle of the same story.