Serendipity is part of human nature and not a purely scientific phenomenon. Three decades ago, an unknown old city tailor had his Eureka Moment which now is part of Kashmir winter’s fashion statement, reports Saima Bhat

One fine day in 1985, a man turned up inside a tailoring shop at old city’s restive Nowhatta. His imported cap needed some quick stitches to fix up. The cap design left the tailor fascinated and triggered a change in him. Three decades later, that change has become city cap camp.

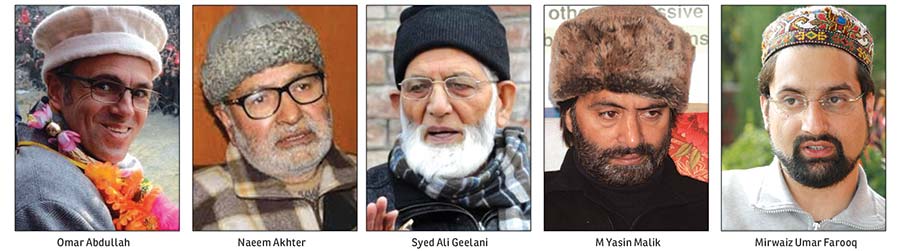

Now Mohammad Maqbool Shah, the octogenarian tailor, is spending his energy in making caps, and not repairing them. The last thirty years have triggered a progressive change in his life, drawing who’s who in the state besides commoners at his shop to buy their choicest headgear.

But the rush hardly seems to bother the elder. His eyes are glued to his slender fingers around which he holds the caps in crisscross fashion with thread floating from his lips. Over the years, his devotion towards caps has sheathed his eyes with thick glasses. Shah doesn’t handle customers. His grandson, Abid, is the default salesman besides a manager, who is also into a cap making.

Shah’s religious devotion doesn’t seem to be an ego statement, rather an artistic desperation to adhere to his art. The same devotion has now created a different niche for him in the market. The moment mercury dips, his shop is abuzz with activity. Besides offering attractive design caps, his ‘Hilal Leather Works’ is stuffed with around 50 cap types.

“Throwing a speciality shop open in the heart of the city dotted with traditional or leather tailoring shops did make certain quarters to write me off at a first go,” says Shah, still stitching a new cap. “But then, I sensed the opportunity and stood firm. Now, when I look back, I don’t mind those who were quick to write my obituary.”

The popularity of his twin shops, his mini showrooms has also encouraged his granddaughter, Sheeba Bashir, an MBAain to be the part of the cap camp. The girl apparently wearing a clear business head stresses that her family has redefined the way Kashmir used to take care of their headgears, a symbol of honour, traditionally.

Behind her surged confidence is their potential to make and market caps —from traditional Cossacks (Karakul) to any foreign cap of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Japan, Australia, England, Russian origin. The caps used to wear by Iraqi ruler, Saddam Hussain and Chechen rebel commander, Ibn al-Khattab is particularly hit among customers. “Our shops’ USP lies in the fact that we make any type of cap in order,” says a confidant Sheeba.

Behind her surged confidence is their potential to make and market caps —from traditional Cossacks (Karakul) to any foreign cap of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Japan, Australia, England, Russian origin. The caps used to wear by Iraqi ruler, Saddam Hussain and Chechen rebel commander, Ibn al-Khattab is particularly hit among customers. “Our shops’ USP lies in the fact that we make any type of cap in order,” says a confidant Sheeba.

Caps having a blend of wool, fur or suede sell like hot cakes in winters. Theirs aren’t just caps, Sheeba continues, but a “style statement”. Right now, the Pakol cap continues to be at the centre-stage.

The traditional Afghan cap, Pakol—an “insignia of rebellion”—attaining its peak of popularity in Kashmir during the nineties is a worldwide fad. Sensing popularity of the cap, Shah responded, and made them available in bulk.

But other than making the popular caps, the shop is equally popular for making innovative design caps. “Marketing is all about hooking customer’s attention,” Sheeba believes. “We do that by constantly playing with fabrics, colours and designs.” Among their new line of caps includes baseball cap style, bob caps, six-panel caps, tweed caps, leather caps, one piece caps, Pashmina caps and now Kani pashmina caps.

Caps carry different price tags. At their shops, a range between Rs 250 and 20,000 is available. A number of caps sold and sales generated in a season remains a “private matter” to Shahs, but given the rush, one can only imagine the brilliance of business.

And to add their growth story, Sheeba says, many Kashmiri traders are now making a bulk purchase from them to sell the caps in countries like Oman, Dubai, and even USA.

Reaching this stage in their trade wasn’t a cakewalk. There was a time when Shah would register no sales for days together. Besides the fascination triggered in him by that imported cap in 1985 came at a huge price. In the same year, with his fascination still at infancy, he lost his son Hilal to a bullet when Nowhatta had erupted in anti-establishment protest. To keep his son’s name alive, he named his twin shops – Hilal Leather Works. Three decades later, his son’s name continues to be alive.