As tens of thousands of Kashmiris were pushed out of the valley by hunger, poverty, exploitation and fortune-hunting during despotic Pathan, Sikh and Dogra rule, Punjab got a sizeable Kashmir community. Business apart, they played a major role in the Indian subcontinent’s freedom struggle and were principal participants in a situation that led to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, 100 years ago, writes Masood Hussain

Writing about the seasonal migrations of the Kashmir community to Amritsar, the Chandigarh newspaper Tribune gave details about the historic connections between the two places. Various localities of the walled city had clear Kashmir identities and the community has contributed towards the social and economic life of pre-partition Punjab.

“Kashmiri Imambara – a place of worship for Shia Muslims – situated in the Lohgarh area in the walled city is a world in itself,” the newspaper reported on January 26, 2006. “About five to seven families who live here had a Kashmiri background, as their immediate ancestors had migrated from the valley about 100 years back.”

Over a century old Imambara, according to the newspaper, was constructed by Syed Nath Shah, who migrated to Pakistan post-partition. “However, in 1962, Safdar Qazam Mir from Kashmir reclaimed this place. Later, he returned to Kashmir. Kasim Ali, Gulam Hussain and Syad Asadulla were among those who dwelled there.” At a later stage, the Imambara land was reportedly given to people who had migrated to India post-partition. “There is also a mosque in Kashmiri Imambara, which is maintained by the families residing there,” the newspaper noted.

Punjab, the immediate state in the Indian plains, had an impressive Kashmir community. Census data suggested that in 1818, there were 179020 Kashmiris settled in Punjab, a number that rose to 225307 in 1891 headcount. This population was more than the population of Srinagar in 1891 when only 118960 people were living in the capital city.

The cultural assimilation of the Kashmir community in Punjab was gradual. Against 49534 Kashmiri speakers in 1881, the numbers gradually dwindled: 28415 in 1891; 8523 in 1901; 7190 in 1911; 4690 in 1921. Then all of a sudden, the numbers were too small to be recorded as the strong Punjab culture overtook the subsequent generations. But that is what happens in migrations.

The big question, however, is why all these people left Kashmir? The answer is a mixed bag. There were four sections of emigrant Kashmiris having different reasons to leave the valley.

A section of elites would normally leave Kashmir to work for the administration in the plains of India. This process was in vogue even before the Mughals’ took over Kashmir. These elites were experienced karkuns who knew how to manage people. Mostly, Kashmiri Pandits, the spurt in this kind of migration started after the Sikh Durbar annexed Kashmir. During the Sikh rule, Ranjeet Singh’s finance minister was Raja Dina Nath, a Kashmiri Pandit. He was one of the signatories of the Treaty between the British and Punjab after the first Anglo-Sikh war. His influence led hundreds of Kashmiri Pandits to leave Kashmir, and in Amritsar, they had their own locality Kucha-e-Kashmiri Panditan.

In the post-mutiny days when the army of Maharaja Ranbir Singh fought for the East India Company against the mutineers, mostly Muslims, the government exhibited a huge appetite for the Persian-English knowing babus in the Company government. Most of the jobs that were created were filled by the Kashmiri Pandits.

The other section, also not very big, was that of traders. They would usually handle the Pashmina trade on the Kashmir-Punjab axis and bring in a lot of stuff that the Kashmir market would require. Some of them eventually settled in the plains of Punjab, North Western Frontier Province and in Bengal. They were mixed groups, Muslims as well as Pandits.

But most of the Kashmiri diaspora in the Indian plains were the common Kashmiris who would escape the abject poverty of the ruling elite in Kashmir. The worker emigration witnessed a spurt in Afghan rule and continued unabated throughout the Sikh era and the Dogra rule in the nineteenth century. Mostly, artisans, they moved out to Punjab as most of their earnings would go to the coffers of the rulers in Kashmir. After a sizeable population of them settled in Punjab, the British India government started making efforts to access raw material from Ladakh so that they can create a parallel Pashmina shawl centre in Punjab. This, they did with great difficulty as Gulab Singh after annexing Ladakh and later purchasing Kashmir threw up spanners in the raw material supplies to Punjab.

But the major section that migrated to Punjab comprised people who were escaping hunger. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while some famines followed the floods, there were peculiar famines that were the outcome of despotic misrule or the manifestation of their ego. There has not been any history work or a travelogue about Kashmir that has not shed tears on what famines did to Kashmir.

In the 1832 famine, parents even sold their babies for food. The 1877 famine devoured three-fifth of Kashmir population. It was so compelling that Dogra rulers withdrew the ban on the flight of people from Kashmir. Since the rulers were filling their coffers with the output of the Kashmir working class – the artisans, peasants and other workers, they had blocked the passes to stop the flight of the people. In certain cases, the property of the fleeing population was even seized. In the wake of the 1877 famine, that system was withdrawn and rehdari system was restored.

All these factors led the sizeable Kashmiri community to settle in Punjab. Though most of them lacked the right to own properties initially, some of the influential sections may have acquired properties later. Some of them studied in the best schools and colleges of British India and a few of them travelled offshore to get educated in the best universities in the world, especially the United Kingdom. They were always concerned about the tragic situation that despots brought to Kashmir.

With some difference in the time, the freedom movement of India and that of Kashmir began, almost simultaneously. While people like Allama Sir Mohammad Iqbal were engaged in the Kashmir freedom movement, a few exclusively contributed to India’s freedom movement. One of them was Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew.

Kitchlew’s ancestor Ahmed Jo had left Baramulla in Kashmir in 1871, a few years ahead of the history’s major famine and settled in Punjab, and set up his Pashmina shawl and saffron business. There, Jo got in touch with the high-end clientele including the dynasty of the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Maharaja of Jodhpur whom he would supply Kashmiri goods for decades.

On January 5, 1888, Saifuddin was born to Azizuddin Kitchlew and Janmali. He was the fourth of their five children. After schooling at the MAO School at Amritsar, Saifuddin went to AMU and Agra and finally went to Peterhouse Cambridge in 1907. Later, he did his PhD from Munster University in Germany in 1913. During his studies, he was mentored by George Bernard Shaw and Bertrand Russell. He joined the bar in 1915.

After marrying the daughter of Khan Bahadur Mohammad Hafizullah, a Kashmir lawyer, Kitchlew was elected Municipal Commissioner of Amritsar city in 1919.

In March 1919, British India initiated the Rowlatt Act (the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act), on basis of the recommendations of the committee led by British judge Sir Sidney Rowlatt. The Act authorised the government to imprison any person suspected of terrorism in India for up to two years without a trial, strictly monitor the media, arrest without warrants and detain without trial. Kitchlew was one of the top leaders who rebelled and took the case to the people and started mobilising the masses. It was in response to their activities that a protest rocked the streets of Amritsar on April 9, 1919. The Company officials took a strong exception to the protest and immediately arrested Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal and sent them to Dharmshala.

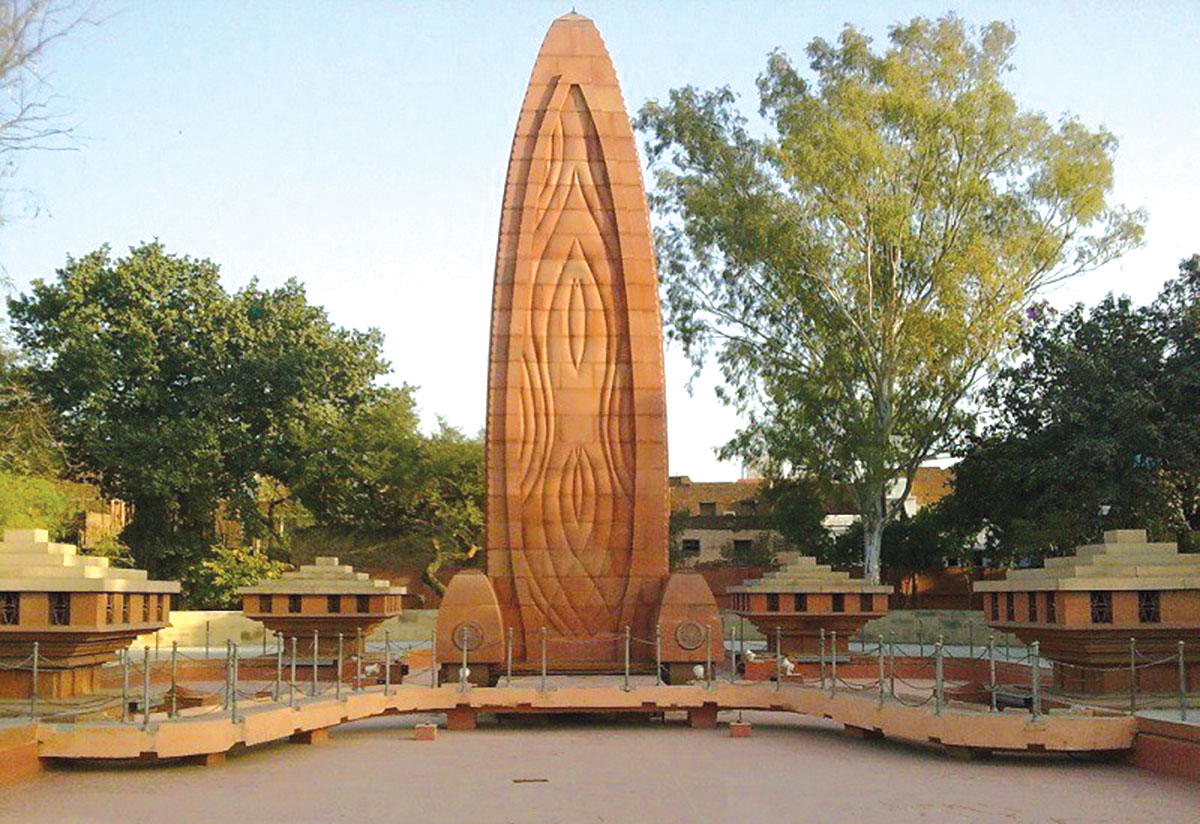

On April 13, 1919, the British authorities enforced sort of a curfew but the Baisakhi gathering was in the Jalianwala Bagh. Interestingly, there were Hindus and Muslims in good numbers. This infuriated acting Brig-Gen Reginald Edward Harry Dyer, who ordered firing on the gathering for almost 10 minutes after sealing the only exit and entry point. This massacre was a major landmark in the history of India’s freedom struggle and is considered as the massacre that ended the Raj.

The exact death count is not known but the government had admitted 379 deaths and the local civilian administration 484 deaths. There are claims the deaths being as huge as 1300, even more. Of the 379 martyrs that Jalianwalla Bagh Museum displays, there are 14 Kashmiris – the youngest being a seven-year-old Mohammad Ismael, the son of Karim Din, and the oldest being 44 years old Ghulam Mohammad, son of Jan Mohammad Kashmiri. Some researchers say more Kashmiris were in the death list.

This milestone event in the history of the Indian subcontinent’s freedom struggle had Kashmir involved in the core of it. Later, the British tried Kitchlew and many others for a series of violations of the law, including waging war against the state. Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal were sentenced to transportation for life as Dr Mohammad Bashir was sentenced to death. They were, however, set free in December 1919.

In the Amritsar conspiracy case, a number of cases were registered and people arrested. Of the 151 people sentenced to death from Amritsar, almost 30 were Muslims. In the case of a murder of an Englishman in Rego bridge, two persons were charged – Mani and Muhammad Shafi, both Kashmiri Muslims. Kitchlew was quoted saying in Delhi in 1953 that Abdul Aziz, a Kashmiri artisan, was sentenced to death in the Alliance Bank murder case. In fact Miles Irving, the then Amritsar Collector, had held Kashmiris responsible for the rioting.

Besides, Kitchlew was publishing Tanzim and established Swaraj Ashram in 1921for training youth for the freedom movement. While most of the Kashmiri community migrated to Pakistan after partition, Dr Kitchlew was a strong opponent to the two-nation theory. His five-level Haveli in Qatra Sufaid (Lahori Gate) was destroyed in the partition fires forcing him to migrate to Delhi. In 1951, he was made the lifelong trustee of the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial Trust, with Moulana Abul Kalam Azad and Nehru. He, however, stayed away from politics (despite being a Congressman) and was involved more in the Indo-USSR relations that gave him the honour of being the earliest recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize in 1952. He died on October 9, 1963. He had spent 17 years in jail during his life.

While India Posts released a postal stamp in Kitchlew’s name in 1989, there are two books on Kithclew, both written by his relatives. Open source details suggest one of Kitchlew’s five sons was Toufique, whose son F Z Kitchlew also authored a book Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew: Hero Of Jalianwala Bagh. Toufique lives in Lampur in Delhi outskirts. Four of Kitchlew’s five daughters migrated to Pakistan and settled there. Zahida, his fifth daughter, married famous Malayalam music director M B Sreenivasan. In Ludhiana, a housing colony is named Kitchlu Nagar after him. In 2009, the Jamia Milia Islamia created a Saifuddin Kitchlew Chair also.

Post partition, a new situation took over. Punjab was the key area where most of the massacres took place. The demography was completely changed. Most of the Kashmiri Muslim community migrated to Pakistan and were eventually part of the elite that built the country.

“Ninety-year-old Fakir Mohammad has been guarding the only graveyard of the Kashmiri Muslims situated in Sultanwind area for five decades now,” the Tribune reported. “He is one of the oldest persons of the Kashmiri Muslim community who migrated to Amritsar and settled here during partition,” Fakir told the newspaper that the graveyard land was donated by Maharaja Ranjit Singh to the Kashmiri Muslims. “But most of the land has now been encroached upon by other residents,” he was quoted saying.