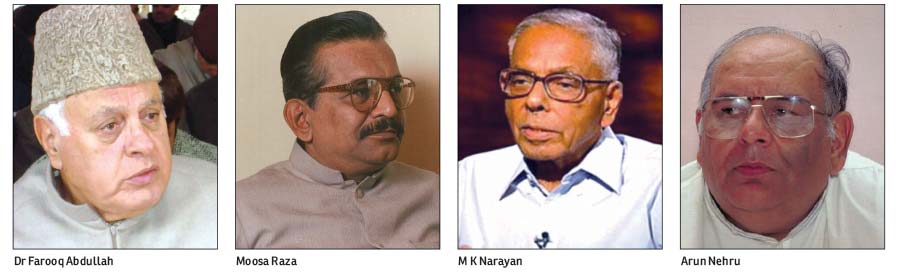

During the amorphous years of militancy that coincided with Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s ascend to first Muslim Home Minister of India, JKLF kidnapped his daughter, a young medical intern. Over the years, there were various accounts of that crisis that led to the first exchange of a hostage with five detained militants. On the 26th anniversary of that event, Kashmir Life publishes the first-hand account of Moosa Raza, the then Chief Secretary who was part of the crisis management

I was the Chief Secretary of J&K in 1989. In December of that year, the V P Singh government had just taken over after defeating the Congress. A 17-member council of ministers took over on December 5. Prominent amongst them were George Fernandes, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed, Sharad Yadav, Arif Mohammed Khan, Ram Vilas Paswan, Murasoli Maran, Maneka Gandhi and others. Sayeed who hailed from Kashmir, became the home minister. T N Seshan, who had earlier been Cabinet Secretary in the Rajiv Gandhi government, was continued by V P Singh in that post. But it was well known that in view of his proximity to Rajiv Gandhi, his days as Cabinet Secretary were numbered.

The chief minister of J&K, Farooq Abdullah was heading a coalition government of the National Conference and Congress. It was also well known that this was not a situation to the liking of the new government in Delhi. The fact that there was no love lost between Mufti Mohammed Sayeed and Farooq Abdullah was the talk of town in J&K and the bureaucracy was rife with speculations that Dr Abdullah may not last long in his post. The Mufti believed-that Dr Abdullah was a mere playboy, more interested in his helicopter and his golf than in looking after the state. He held Farooq squarely responsible for the sporadic militant activity in the state. He told me as much during my later meetings with him.

I came to Delhi on December 6, 1989, for some important meetings with the Cabinet Secretary and the Planning Commission and had an appointment to meet the home minister in the afternoon of Friday, December 8. This was my first meeting with him after his taking over as home minister and it was by way of a courtesy call. I was busy in the forenoon and when I had reached North Block, at 4 pm, the minister’s personal assistant told me that the home minister had just received news of the kidnapping of his daughter, who was a medical intern, and was quite perturbed. When I was ushered in, Mufti was on the phone. He gestured to me to take a seat. The conversation was in Kashmiri, but I could make out that it was about the kidnapping. When he kept down the receiver and turned to me, I could see that he was calm and collected.

For a man who had received the news of his daughter’s kidnapping minutes before, he showed no sign of excitement or agitation. The only remark he made to me was “I would not have been so anxious had they kidnapped my son.” It was from him I learnt that as Rubaiya was returning home from the hospital in a minibus, she was stopped en route near Navagam and taken away by four armed militants. Sayeed’s house is about 500 feet from there. Since then, there had been no news of her.

From the office of the home minister, 1 proceeded directly to the Cabinet Secretariat. The Cabinet Secretary had been called away by the Prime Minister. I tried to get in touch with the home secretary. He too was not available. I waited until 6 pm when they returned. I was informed that a meeting of the Crisis Management Group would be held. Along with the Cabinet secretary, the director of the Intelligence Bureau, Director of the National Security Guard and DG Joint Intelligence Committee, the home minister himself was present along with Arif Mohammed Khan, and Arun Nehru. There was meagre information available to the CMG at this point of time, beyond the bare facts of the kidnapping. It was, therefore, decided that I should fly to Srinagar to take charge of the state CMG, establish contact with the kidnappers and devise ways and means of getting Rubaiya released.

I, therefore, returned to Kashmir House to get more details and make arrangements for my flight. The J&K Secretariat was then functioning in Jammu and since Dr Abdullah was away in London for a medical check-up and the Cabinet was in Jammu, my presence in Srinagar was essential.

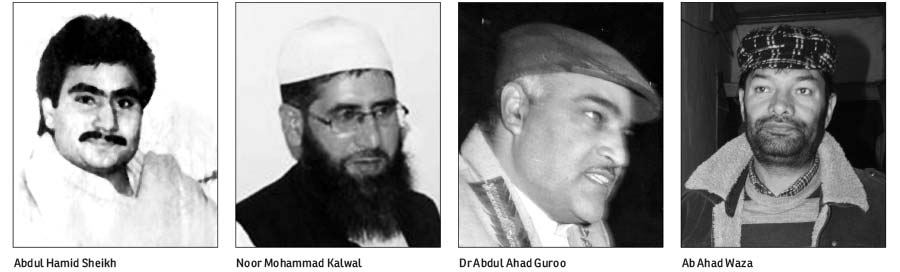

From Kashmir House, I got in touch with the home secretary, J&K, divisional commissioner of Srinagar and other officials. They too had only sketchy information. But by that time, the militants, who belonged to the JKLF had made known their demands for the release of five of their companions headed by Abdul Hamid Shaikh. The latter had been seriously wounded in an encounter earlier and was then hospitalised in the Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences in Srinagar. This demand had been conveyed through intermediaries and the Cabinet, headed by (Mohiuddin) Shah, the senior-most minister in the absence of Dr Abdullah, was seized of it.

While I was engaged in these enquiries, I received a call from the Cabinet Secretary. He told me I should fly back that very night to Srinagar and establish immediate contact with the militants who were holding Rubaiya Sayeed captive. I would be accompanied by Roy, joint director, IB, and Ved Marwah, DG National Security Guard and two negotiators from the home ministry would assist me. A BSF plane was being made ready to fly me back to Srinagar and that I was to be on stand-by. I immediately informed the divisional commissioner in Srinagar to open a control room for me in the police headquarters and make arrangements to receive me and the accompanying party at Srinagar airport.

It was mid-December and cold in Delhi. It was much colder in Srinagar – below zero. I had come to Delhi from Jammu with light woollens, so I was not well equipped to withstand sub-zero temperatures. However, I had no time for such mundane considerations as I was too busy in Kashmir House mobilising and activating all officials of the state Crisis Management Group and non-official contacts in Srinagar to locate the house where the girl was being held captive and to bring pressure on the militants. I talked to several people on the phone that night, as the plane was getting readied.

It was four in the morning when we left Delhi – the four of us in the small plane with DIG, BSF in the pilot’s seat. It was a memorable journey in total darkness as the weather was inclement and all throughout the flight we were guided by Air Force stations on the ground. The pilot could see nothing in the darkness and a couple of times, close to Banihal, we strayed towards the Pir Panjal range and the ground control had to excitedly warn us back to our height and direction.

At 6 am of December 9, we landed at the Srinagar airport, which is not equipped for night landings. It was still too dark to see the runaway. But the DGP and divisional commissioner had made necessary security and transport arrangements. I was straightaway rushed to the police headquarters. On the way, I borrowed a Parka from someone and for the next five days, I practically lived in that Parka.

Dawn was breaking as we gathered in the control room. The DG of police informed me that the Cabinet had informally met in Jammu during the night and had drafted an appeal for the release of Rubaiya Sayeed unharmed and that the named militants may be released in exchange. The consensus of opinion in the control room meeting was that this resolution took away the bargaining position of the administration vis-à-vis militants and would encourage them to make additional demands. There was also grave apprehension expressed about the likely long term repercussions.

Luckily it was only an informal resolution and not much publicity had been given to it.

I ascertained that the JKLF had demanded the release of the following five militants, all of them in prison – Abdul Hamid Shaikh, Gulam Nabi Bhat, Mohammad Altaf, Noor Mohammad Kalwal, Javed Zarger.

On December 9 itself, the JKLF dropped the demand for Javed Zargar and replaced it with Abdul Ahad Waza.

In the meantime, I established contact with the deputy director of Intelligence Bureau, A S Dulat to obtain his input through his good offices, two unofficial mediators were located. One was Zafar Meraj, a journalist and the other was Vijay Dhar, the son of Dhar, who had been in the Central Cabinet of Indira Gandhi. I also got in touch with several others including Sofi of Srinagar Times, Sarwar, Miss Shabnam, daughter of Abdul Ghani Lone, etc.

In the meantime, I put the state CID and IB to locate the house where Rubaiya Sayeed was being held captive. During the course of the next three or four days, they located several houses in Baramulla, Sopore, Maharaj Ganj and Rawalpora. However, on investigation, they all turned out to be false leads.

Photo Courtesy: Sunday Magazine

The police and the paramilitary forces were deployed for nakabandi of the city, patrolling in identified areas by paramilitary and army was intensified and the police spread out with photos of Rubaiya Sayeed to make enquiries at various locations. Public opinion was mobilised to bring pressure on the militants and the JKLF by getting statements issued by opinion leaders, political personalities, etc. Unobtrusive surveillance of all known contacts of militants was intensified.

Our efforts were to keep the negotiations on, to try to get the girl released without acceding to their demand and in interim to locate the “safe house” and get her released through commando action.

It was ascertained that Abdul Hamid Shaikh was in a critical condition in the SKIMS. He was in the ICU with various life support systems attached. The militants demanded that he should be handed over to the Pakistan Embassy. We wanted to know from them whether the Pakistani Embassy would be willing to receive him. Then the militants changed their stance and said Hamid Shaikh should be provided with a special plane and flown out of India to a third country. After many messages had been exchanged back and forth through the intermediaries, the militants said that Hamid Shaikh should be flown to London. We offered that if they were so anxious about his injuries, we would shift him to AIIMS in New Delhi and put him under the best treatment.

In the meantime, the state administration and the IB were using several well-wishers to build up pressure on the militants. One of the weak points of the militants was that since they always claimed a high moral ground for all their actions — justice for the people of Kashmir, fairness in elections, closure of bars and cinemas, etc, release of innocents, prevention of atrocities etc, their having captured an innocent girl was not involved in any way went against all their proclaimed ethical values. A major thrust of my negotiating grounds was based on this approach.

In the first two days after the kidnapping, there was widespread condemnation of the kidnapping in the press. But as the days passed, there was a noticeable shift. There was general sympathy with the plight of the girl, but the pressure was on to release the militants and get the girl released. Even the English language press in Jammu, generally hostile to Farooq Abdullah, and favouring the new government in Delhi, slanted its news in favour of getting the hostage released forthwith. In fact, several reports commented unfavourably against the government for prolonging negotiations. In the meantime, the militants too were building up pressure by settling deadlines and threatening to kill the hostage if their demands were not met.

As negotiations progressed, it was found that parlaying through intermediaries was a time-consuming action. Neither the IB nor the other agencies could make a break-through in locating the “safe house”. Every time a message was passed on to militants, it took ages to get back a reply. The militants did not trust the telephone system and were apprehensive that we would trace the call. Meanwhile, the Crisis Management Group in Delhi was in continuous session and the Cabinet Secretary was literally on my back.

He wanted half-hourly reports. Since communications between the control room in Srinagar and the Cabinet Secretariat was neither fail-safe nor secure, I had to communicate with him from the secure line in the IB headquarters on the Gupkar Road. I had, therefore, to use the IB control room more often than the police headquarters. Even after that, the Cabinet secretary was not happy. The IB believed that all conversations between the state and the Centre were prone to be tapped even in the telephone exchange as the militants had sympathizers here. So the Cabinet secretary preferred that I communicate with him in Tamil, as he believed that there was a remote chance of Kashmiri militants knowing that language. I had therefore to resuscitate my school Tamil — a language in which I had not communicated anything sensitive and serious in decades.

Ultimately, at my behest, the militants agreed for direct talks on December 10, by which time Dr Farooq Abdullah had returned to Srinagar, cutting short his stay. He was rather unhappy at the pressure that was being brought by the Centre for releasing the militants in exchange for the home minister’s daughter. He was apprehensive that this would lead to a spate of such kidnappings in the future and the state government will be called upon to provide security to all VIPs and their siblings who until then were moving about freely.

The Cabinet secretary was extremely reluctant to allow me to proceed into the heart of Srinagar for direct talks with the militants. He was apprehensive that if the militants made the chief secretary also captive along with the home minister’s daughter, the problem would be further compounded. In such an eventuality, the government of India would be made to look foolish and questions would be raised as to why the chief secretary was permitted to expose himself to such a risk.

It took a number of discussions among the intermediaries, the Cabinet secretary and me before I could give him reasonable assurance of my safe return from the militants’ den.

Accompanied by A S Dulat, deputy director IB, I got dropped at the Nalamar and from there we were picked up and taken to a house in the deep interior of the old Srinagar. We were guided through a maze of many lanes — perhaps to confuse us. We climbed to the first floor of a house where we met Abdul Majid Wani, the father of Ishfaq Wani, then a top leader of the JKLF. We had the feeling that the JKLF leadership was somewhere on the ground floor.

During the subsequent prolonged negotiations, the militants demanded that Hamid Shaikh and his family should be sent to either Iran or Dubai. Once the message of their safe landing there was received, the girl would be safely released. In the alternative, Hamid Shaikh should be released in Srinagar and delivered to them in a car with safe passage to cross over to Pakistan. Or, Hamid Shaikh should be taken by the police to the Pakistan border with instructions to the BSF to allow them to cross over. Since none of these proposals was acceptable to us, the negotiations got prolonged. I argued that kidnapping an innocent girl was totally un-Islamic, holding her captive against her will was against all human and Islamic norms, and harming or killing her would amount to a heinous crime both against the religious and moral laws. They countered with the argument that Abdul Hamid Shaikh and the four others were equally innocent and the government was holding them in jail illegally and immorally. Their only crime, they claimed, was to have protested against the “rigging” of election in 1987. To this, I gave them an assurance that once the girl was released unharmed, I would myself examine the case of each of the detainees and if found innocent, I would release them forthwith. I intended to carry out my promises if they held to theirs. This proposal finally found favour with them.

During the subsequent prolonged negotiations, the militants demanded that Hamid Shaikh and his family should be sent to either Iran or Dubai. Once the message of their safe landing there was received, the girl would be safely released. In the alternative, Hamid Shaikh should be released in Srinagar and delivered to them in a car with safe passage to cross over to Pakistan. Or, Hamid Shaikh should be taken by the police to the Pakistan border with instructions to the BSF to allow them to cross over. Since none of these proposals was acceptable to us, the negotiations got prolonged. I argued that kidnapping an innocent girl was totally un-Islamic, holding her captive against her will was against all human and Islamic norms, and harming or killing her would amount to a heinous crime both against the religious and moral laws. They countered with the argument that Abdul Hamid Shaikh and the four others were equally innocent and the government was holding them in jail illegally and immorally. Their only crime, they claimed, was to have protested against the “rigging” of election in 1987. To this, I gave them an assurance that once the girl was released unharmed, I would myself examine the case of each of the detainees and if found innocent, I would release them forthwith. I intended to carry out my promises if they held to theirs. This proposal finally found favour with them.

The negotiations concluded when Wani suggested that the Chief Secretary should appeal on the television for the release of Rubaiya Sayeed and they would release her without condition, trusting that the chief secretary would subsequently honour his commitment.

When we returned three hours later from the parleys, I rang up the Cabinet secretary to find him in jitters. He thought that we had both been captured and was waiting to receive fresh demands from the militants. After apprising the chief minister of these developments, and after getting clearance from the Cabinet Secretary, I recorded an announcement for the radio and television at 6.30 pm appealing to the militants’ brotherly spirit for the release of the innocent girl. I assured the militants that if the girl was released unharmed, no charges of kidnapping and abduction would be pursued and the best medical treatment would be provided to Hamid Shaikh. At 7.30 pm, the appeal was broadcast. I was expecting a favourable response from the militants.

While I was busy with these negotiations, I received information through the CID that some individuals had approached the militants and opened up separate negotiations with them. The names of Justice Moti Lal Bhat of the Allahabad High Court, who had recently been transferred there from the J&K High Court was prominently mentioned. Two other names — Mian Qayum, a well know lawyer and Dr Guru of the SKIMS too were mentioned in conjunction with that of Justice Bhat, who was reputed to enjoy the confidence of Mufti Mohammed Sayeed.

On the 11th in the morning, while waiting for the response of the JKLF to my appeal, the Cabinet sub-committee met under the CM’s chairmanship to review the progress of the negotiations. Taking note of the intervention of unauthorised individuals into the negotiations, the sub-committee “affirmed that the chief secretary is the only authorised representative of the state government to hold negotiations in this matter and no other person has any authority to talk or do anything on behalf of the state government.” The subcommittee also “appealed to the abductors of Dr Rubaiya Sayeed to release her unharmed immediately, to uphold the honour of the people of the state and in the best traditions of Kashmir.” This was given wide publicity in the media.

However, on the afternoon of the 11th when I met Zafar Meraj in the IB headquarters on Gupkar Road, I was shocked to hear that the militants had made a total volte-face. In fact, Meraj said that even his life was in danger. When I enquired why he was so perturbed I learnt that in the intervening night, the JKLF had learnt through another intermediary that the government of India was prepared to release all the five militants if Rubaiya was released forthwith. In fact, the JKLF had come to believe that Zafar Meraj and the state government were taking them for a ride, with while the home minister and the government of India were agreeable to the exchange.

However, on the afternoon of the 11th when I met Zafar Meraj in the IB headquarters on Gupkar Road, I was shocked to hear that the militants had made a total volte-face. In fact, Meraj said that even his life was in danger. When I enquired why he was so perturbed I learnt that in the intervening night, the JKLF had learnt through another intermediary that the government of India was prepared to release all the five militants if Rubaiya was released forthwith. In fact, the JKLF had come to believe that Zafar Meraj and the state government were taking them for a ride, with while the home minister and the government of India were agreeable to the exchange.

When I checked up with Delhi, I was asked to proceed with the negotiations using the good offices of Justice M L Bhat to get Rubaiya released, as she had been held hostage for almost three days. I was told that not only the home minister but also all his colleagues were perturbed with the prolonged negotiations and wanted the matter to be settled as quickly as possible.

This news was received both by me and the chief minister with grave concern, as it negated all the efforts at negotiations made until then. Moreover, since I was expecting to get the girl back without an immediate exchange, it would be in the best national interest to wait. But my arguments did not find any favour in Delhi.

This changed the situation drastically. Accompanied by the divisional commissioner, J&K, I met Justice M L Bhat by appointment. In his drawing-room, we found Dr Guru and Qayoom. Speaking on behalf of the militants, Dr Guru mentioned that if it was found difficult to release Hamid Shaikh because of his condition, he could be replaced by anyone of two others, Yaseen Malik or Javed Nalka. This was a new gambit and we had to make further inquiries. It was, however, more or less clear, in view of the intervention of Justice Bhat and the assurances they had received from him that the JKLF would not settle for anything less than the release of the five militants. Moreover, they stipulated that the exchange would not be simultaneous. We were to release the five militants into the hands of the three mediators, withdraw the police from certain localities and wait for three hours when Rubaiya would be brought back and handed over to us in Justice Bhat’s house.

This proposal was not acceptable to us. I pointed out that once we had released the militants, we had no guarantee that the JKLF would honour their side of the bargain, particularly when there was a gap of three hours. Anything could happen during these crucial three hours. Even if we trusted the JKLF to keep the bargain, we had no way of knowing whether any other interested militant group, opposed to JKLF ideology, may not hijack the girl while she was on the way to Sonawar. All these issues perturbed me considerably, though Justice Bhat was confidently adding his assurance to that of Dr Guru and Mian Qayum. Anyway, the negotiations ended on a stalemate on the evening of Tuesday, the 12th.

I reported all the details of the negotiations to the Cabinet subcommittee and the Cabinet Secretary. The state Cabinet subcommittee met at 10 pm.

Dr Farooq Abdullah, who had all along been opposed to the release of the militants, fearing the long-term repercussions, was even more perturbed at this turn of events. It was under extreme pressure from the Centre that he had even agreed to release the militants. But to be faced with the situation of having to release the militants without even getting the girl simultaneously, and having to wait for three hours before knowing whether the government has been taken for a ride or not, was not the kind of situation either he or I were prepared to face. He was prepared to tender his resignation there and then. I think he spoke to the governor, General Krishna Rao, who perhaps restrained him from precipitating any action at such a critical moment.

With the CM’s consent, I called a press conference at 12 midnight on December 12, and released the following statement, which speaks for itself.

“The state government has been making concerted efforts for the last four days to secure the safe release of Dr Rubaiya Sayeed. Contact has been established with the militants holding Dr Rubaiya Sayeed through various intermediaries.”

“The militants have been demanding the release of five of their colleagues, who are in custody on various charges. The safety of the innocent girl has been of paramount concern for the state government. In view of the human considerations involved, the state government decided to release the five persons in exchange for the hostage. All the five named are now in Srinagar to facilitate a simultaneous exchange to end the agony of a helpless girl and of all those who have felt and expressed their concern for her.”

“However, at the last moment, the militants through their intermediaries have not agreed to a simultaneous exchange but have demanded prior release of these persons with a gap of three hours.”

“The Cabinet sub-committee met under the chairmanship of the chief minister to consider this stand. Since the safety and secure release of the girl is of paramount importance and since any gap is fraught with grave consequences to the safety of the hostage, the state government renews its appeal to her captors to agree to a simultaneous exchange.”

I communicated the views of the state Cabinet to the Cabinet Secretary immediately after the press conference. He agreed that the time gap of three hours was not acceptable and that I should continue to persuade the militants to agree to a simultaneous release.

But while I was in session with the CMG, I received another call from the Cabinet Secretary at 1.30 am of the 13th. In a rather stiff and formal tone, he said, “This is the Cabinet Secretary to the government of India, speaking to the Chief Secretary of the state of J&K. I am speaking from the chamber of the Prime Minister of India. The Cabinet Secretary desires the state government to note that it is their undiluted responsibility to ensure the safe release of the hostage without any injury to her and we expect that all action you take will be consistent with this requirement” (emphasis added). Having made that statement, he abruptly broke the connection.

I had noted down the statement of the Cabinet secretary verbatim in my diary. I read it out to the other members of the CMG who were still waiting for me in another chamber. I wanted their interpretation of the “ultima-tum”, to me it appeared as an ultimatum, couched as it was in such formal terms. Various interpretations were advanced. The only thing obvious was that the girl had to be got released safely at all costs. This ruled out even commando action, even if we had located her whereabouts. The state government will be held squarely responsible in case of any failure. But it was not clear whether the government of India agreed to a simultaneous release, or desired us to accept the militants’ terms.

I waited for half an hour and rang up the Cabinet Secretary in his chamber, hoping that he would have returned by then. He had. I spoke to him in Tamil and desired to know the implications of his message to me from the PM’s chamber. He told me clearly that it meant I had to get the girl released without any harm at all costs. What about the time gap, I asked. You have to take Justice Bhat’s assurance for that, he said. He also informed me that two Cabinet ministers, I K Gujral and Arif Mohammed Khan would be reaching Srinagar by a special flight in the early morning and I should apprise them of the status.

From the police headquarters, I rang up the chief minister at his residence. He had just then gone to bed. I told him that I had received an important message from the Cabinet Secretary and wanted to apprise him of it personally. At 2.30 am, accompanied by the divisional commissioner, I met the chief minister and apprised him of the Cabinet secretary’s message and my subsequent conversation with him. He was extremely perturbed. “They will destroy Kashmir,” he said. I could note the agony in his voice. But reluctantly, he told us to go ahead and negotiate with Justice Bhat and the others.

At 3 am, we again went to Justice Bhat’s house and resumed negotiations. After prolonged negotiations, the following terms were agreed upon;

The five militants would be set free three hours before the handing over of Rubaiya Sayeed.

Three hours would be the maximum gap, but efforts will be made to hand her over earlier.

The five militants will be brought to Justice Bhat’s house and handed over to the mediators.

The police will withdraw after the four other militants are identified by Hamid Shaikh.

They will not be arrested, shadowed or trapped unless for an offence committed after their release.

Police force posted at the exit points of the outer ring of Srinagar and bridges specified by the mediators would be withdrawn for three hours.

The mediators will not be shadowed for three hours.

There will be no celebrations/processions organised by the supporters of JKLF on the release of militants.

The three mediators stand guarantee for the safe handing over of the girl at Justice Bhat’s house within three hours.

Justice Bhat will okay this agreement along with the team assisting him. The team itself will go with the militants and take charge of the girl.

By the time we concluded these negotiations, I received an urgent message from the chief minister to proceed to his residence. I reached there at 6 am to find that I K Gujral and Arif Mohammed Khan had arrived, accompanied by the director of IB, M K Narayanan. For two hours, I briefed them of my discussions, with the mediators. Gujral complimented me and the state government in the way the negotiations were conducted. They felt that since there was no other option, this was the best possible solution.

Thereafter, I apprised the Cabinet secretary of the terms and conditions agreed upon. It was 11 am, on the 13th by then. He said he would like to get the clearance of the home minister and the Prime Minister. At 11.50 am, I received his clearance.

The state Cabinet sub-committee again met at 12.30 pm. Here is its resolution: “The CSC presided over by the chief minister was apprised of the terms of settlement arrived at and the approval given through the Cabinet Secretary of the home minister and the Prime Minister of India. The CSC considered the merits and decided to approve the agreement.

“CSC desired that the law and order should be maintained in the city and the police and paramilitary forces should be put on maximum alert.”

After issuing necessary instructions to the DGP, CRPF, BSF, etc, I communicated the approval of the state government to the mediators at 12.30 pm. The police had to make necessary arrangements to collect all the militants after following the due procedure. I arrived at Justice Bhat’s house and the militants were brought there and handed over to the mediators at 3 pm.

The next three hours I spent were of excruciating tension. Even though I had obtained all the necessary approvals, I was aware of the fact that they were all oral. If anything went wrong and for some reason, the girl did not turn up now, it would be my neck on the block. There was every chance that everyone would wash their hands off the responsibility and I would be accused of having released the militants off my own bat.

As I paced the drawing-room of Justice Bhat’s house, like a caged tiger, for three hours, I reviewed all possibilities of where things could go wrong. I had some members of the CMG with me. I consulted them also on the worst case scenarios and all possible responses from our side. Many suggestions came up and I initiated many contingent steps.

At 6 pm, the girl had not turned up. Justice Bhat suggested that we give half an hour grace time. The minutes ticked by with agonising slowness. At 6.30 pm, I called a meeting of the CMG for developing a contingency plan. At 7 pm. Justice Bhat and Mir Mustafa threw up their hands. Mir Mustafa, in fact, voiced his apprehension that another group might have hijacked the girl en route.

At 7.15 pm the car arrived with the girl. We took the girl to Mufti Mohammed’s house in Navagam and handed her over to her family. I K Gujral and Khan were both present. The special plane that had brought them was still at the airport. She left for Delhi accompanied by the two ministers in the same aircraft.

Neither I nor the police even got the opportunity of debriefing her subsequently. She could have given us valuable information. I could not even learn where she had been held captive. It was almost 10 years later that somebody showed me the burnt-out ruins of a forest department hut in the heart of Dachigam sanctuary as the place where Rubaiya Sayeed had been held captive for five days.

A couple of years later, I met Seshan, who was then chief election commissioner, at the VIP lounge of the Delhi Airport. He introduced me to a couple of eminent journalists and a film personality who had become an MP. As we were walking towards the security clearance, I asked him, “I have always wondered about the sudden change in your approach when you dictated to me that ultimatum in the early morning of 13th December. What was the cause of that?”

“The game was much bigger,” he said, with a sardonic smile.

“And what was that?” I asked. But his reply leads to another story.

(First published in The Asian Age in January 2000)