New Delhi is countering leaked reports of Chinese incursions by denials, But China’s steady encroachments in Ladakh are an open secret. KASHMIR LIFE assesses the current standoff and the history of border relations of the two neighbours.

Air space violations by China’s Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA) chopper in June, foot patrol incursions into remote Ladakh belts and painting of rocks with Chinese slogans on this side of the divide have triggered lengthy reportages in the Indian media. Apart from many ‘war correspondents’, the J&K Governor, N N Vohra visited the 134 km long salt lake, the Pangong Tso. Pangong Tso is geographically situated in disputed territory with 60 per cent of its length lying in China.

Official media in Beijing has sought to downplay the reports of incursion by accusing the Indian media of raising “war rhetoric”. But ‘experts’ here are already drawing parallels with the tensions that preceded the 1962 war and later in 1986 when diplomacy prevailed over the situation and doused the limping flames. India’s Ministry of Telecommunication & IT is finally going against the ‘Made in China’ mobile sets – after three lapsed deadlines, as intelligence agencies warned these cheap but popular devices might have “embedded elements enabling China to launch a cyber attack.”

For well over half a century, India and China are battling over the colonial legacy – a hazy boundary. Unlike New Delhi, Beijing has reservations over accepting the 1914 Simla accord that demarcated the border between Tibet and India on basis of the 4056 kms long McMahon Line. Chinese maps show some 150,000 sq km of the territory south of the line as Southern Tibet, part of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR).

Off late, the relations between the two countries had started to improve. The rival armies even conducted joint military exercises in 2007 and 2008. Trade is also surging and has already crossed US $ 52 billion in 2008.

In 2003, New Delhi accepted Tibet as China’s integral part and in lieu, Beijing recognised Sikkim as part of India. The unsettled part includes Beijing’s claims over Arunachal Pradesh, which it sees as ‘Southern Tibet’. New Delhi also sees China’s occupation of Aksai Chin as illegal because it considers the region as being part of J&K.

Since Beijing has already settled its border disputes with Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Mongolia, North Korea, Vietnam, and Laos, it is only the McMahon Line that remains unsettled. Because of which tensions are on the rise: Indian Army alleged 270 border violations and nearly 2,300 instances of “aggressive border patrolling” by PLA in the two disputed border regions in 2008. In 2003 the two sides had initiated a serious effort to settle the mutual disputes but the 13th round of that dialogue process failed to offer a way out in June last year. Beijing’s strategic alliance with Islamabad is further adding to the mistrust.

PLA’s intrusion, 1500 meters into Chumar sector’s Mount Gaya (Ladakh) and the retreat after painting the rocks red with ‘China’ on July 31 this year coupled with air space violation by two choppers on June 21 in the same sector ignited the flames of a new ‘cold’ war. Apparently it is still being fought unilaterally in newspapers but reports suggest that there is a movement of men and machinery as well.

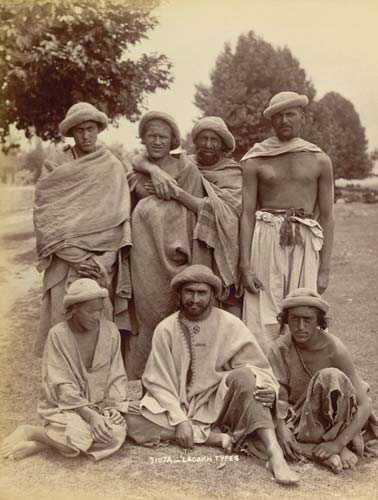

It does not, however, require army’s confirmation that PLA has lately been ‘aggressively active’ in the arid Ladakh desert. It has been almost two years now that the residents in Nyoma have been insisting that instead of Chinese Border Police, it is the PLA deployed all around the border areas. Nawang Norboo, who represents the Nyoma block in Leh’s Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC) recently stated that PLA troubled Chang Pa shepherds in the winter pastures and forced them to leave.

In fact, Deputy Commissioner Leh A K Sahu wrote to New Delhi informing that “Chinese troops had occupied some of the areas in the region and had also threatened the tribes in the area to vacate the land.”

P Namgyal, a former parliamentarian from Ladakh gave some details in a recent interview to a national daily. “There is a place in Ladakh called Dumtsele, where a few years ago, clashes between the PLA and the Indian Army took place. The PLA captured our post there and since then the post is with them,” Namgyal was quoted saying. “Our nomads who migrate to Skagzung, a grazing land near the LAC, had reported that the Chinese Army had helped settle nomads from China in that place. In the past, they were pushed back by the police, but this time too there are reports that they (PLA) have again settled their nomads in the area.” He believes the PLA incursion in Skagzung dates back to January 2009 and not to June.

Another former parliamentarian Thupstan Chhewang said the PLA incursions are “much worse” than those in Arunachal. In a March 2008 interview, he said that the Chinese were building a road on the Indian side of the Pangong Lake. Work was in progress till the Indian objections led to its halt. In Pangong lake, he said, PLA chased an army patrol “four or five kilometres inside the Indian side” of the lake, captured the crew, and took them, prisoners, sometime in 2004 or 2005. Chhewang said Chinese objections led to the removal of a motorable bridge in Dungti belt (in Ladakh) that Changpa tribes were using to take their herds to the pasture rich Chumur and Skagjung on the other side of Indus. Unlike Chinese who encourage their herdsmen to enter Ladakh and settle, the Indian army is discouraging the Pashmina-goat raring Changpas from raring their herds in the border belts, he alleged.

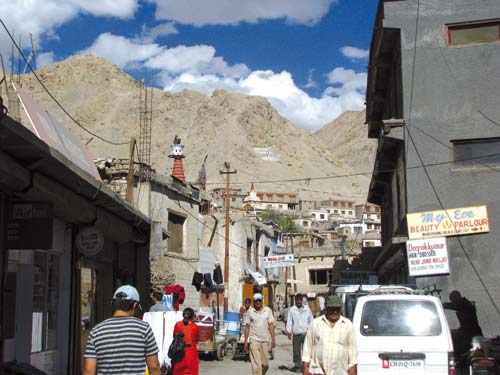

For Chinese troops or herdsmen, Ladakh peripheries are easily accessible. Over the years, Beijing has invested heavily in the border infrastructure especially the roads that make Chinese movement quick and easy. A small village on the other side of Ladakh border post-Demchok is already a roaring market.

Reports in Indian media suggest that Beijing built 6000-km of roads in Nagari belt that adjoins Ladakh and over 16000-km in the Tibet region. Besides, there are 15 operational airfields in Tibet, Yunan and Sichuan provinces, and a network of roads and railway lines almost touching the McMahon Line. In Ladakh, Chinese highway cuts across Aksai Chin and all its outposts in the sector are connected by roads and telephone, unlike those of India.

China has not only invested in border infrastructure near Himachal, Ladakh and Arunachal, but there is also significant infrastructure coming up on other critical corridors as well. It is not the just the Lhasa-China rail link – the world’s highest railway- that China has built there are other strategically important road and rail links coming up elsewhere too. Beijing is building a road link between Lhasa and Khasa, a town barely 80 km from Kathmandu beside the 65-km Syafrubesi-Rasuwagadi road, the shortest route from Tibet to Kathmandu. A rail-link is already in progress to connect Lhasa with Zigatse, the second-largest city in Tibet.

After the 1962 war that killed 3,100 Indian and 700 Chinese soldiers, India evaded infrastructure building close to borders as a strategy, believing that such infrastructure would help the 2.5 million strong PLA make swift inroads into India in case of a conflict. But this strategy had its own costs. It would take a supply mule 16 days to reach Murgo Campt from the Shyok River after crossing the Murgo Nallah more than twenty times. The LAC is almost 15 km away from the Murgo camp. A soldier posted at Murgo pays Rs 25 per minute to talk to his family through INMARSAT even after the tariff is subsidized to the tune of Rs. 70.

After realising that the infrastructure situation has starkly changed on the other side of the McMahon Line, New Delhi took a number of decisions to remedy the situation. Emphasis was given to lay a proper road network alongside the border and to restore and reopen some of the World War II landing sites in all the three sectors viz, Western Sector (Ladakh), Middle Sector (Uttarakhand, Himachal) and Eastern Sector (Sikkim, Arunachal). Though conceived in 2001, the implementation of the plan started quite late in the UPA regime. Sham Saran, a former foreign secretary was tasked to examine the existing infrastructure and suggest improvements. He spent many days in Ladakh in 2007 summer interacting with the cops and soldiers to understand the brass-tacks.

Though the Border Roads Organization’s (BRO) Himank Project has been implementing a network of roads in Ladakh for many years now, the UPA regime is busy building an ambitious highway linking Leh with Daulat Beg Oldi, near the Karakoram Pass, with hubs at Shyok and Murgo. Connecting Demchok (otherwise connected by a 330 kms long road to Leh) with Chushul, Spanggur Gap, Hot Springs and Chip-Chap River, this belt was the main battleground in 1962 conflict.

Within a short span of time, IAF succeeded in renovating Daulat Beg Oldi and Fuk Che airfields in Ladakh. In May 2008, IAF’s AN-32 aircraft landed at DBO, an airstrip at a height of 16,200 feet. A 10-ton aircraft, the AN-32 suits the area better because it can load and unload cargo without switching off its engines unlike the 50-ton, four-engine IL-76.

Switching off engines at high-altitudes hinders restart. Operational between 1962 and 1965, the airstrip was left to disuse after an earthquake in 1966 made it unfit for use. Soon after Fukche airbase, around 2.5-Kms from the Chinese border near Aksai Chin (locally called Lingzinthang), was made operational. Though IAF has given up the idea of reviving Chushul Airbase but reviving the Nyoma Advanced Landing Ground is being pursued. Interestingly, four Sukhoi-30 MKI fighter jets capable of carrying nuclear weapons were deployed in Tezpur, Assam around the same time. Reports suggest that first of three AWACS (airborne warning and control systems) planes will soon be deployed in Ladakh, to act as a “potent force-multiplier”.

But the progress on road implementation cleared by the cabinet in 2006 has not been impressive. Of the 73 road projects approved – Arunachal (27), Uttarakhand (19), J&K (14), Himachal Pradesh (7) and Sikkim (7), only nine were ready by January last.

Right now, there are at least four proposals for tunnel projects costing well over Rs. 3500 crores on the table to make Ladakh accessible round the year. Work on the Rohtang Pass (Himachal) tunnel has already started this summer. The 8.80s km tunnel will reduce Manali-Leh (this highway is sinking for around 1.5 km at Gulaba, 23 km from Manali) travel from 475 km to 429 km. Though for Ladakh it would be around the year road the actual difference would be felt between Manali and Keylong which would come closer by 46 Kms.

Two tunnels are also planned on the existing Srinagar Leh highway that would help manage the Zoji La, the high altitude pass separating Sonamarg with Kargil that remains under massive snow for more than half of the year. Apart from the main 12 km tunnel at the main Zoji La pass, it would have a smaller 3.10 km tunnel ahead on Z-Morh Curve that also gets blocked during winter. Together, their tentative costs are at Rs. 1333 crores.

Another tunnel is planned to tame the Shinkunla pass between Darcha and Padam-Nimu. It is expected to cost 525 crores for a four km length. Border Roads Organization has already issued tenders for seeking a DPR for this project that would make access to Zanskar easy.

The tunnels are over and above three major road projects already in different stages of implementation. Under the Prime Minister’s Reconstruction Plan, 420 km Srinagar-Kargil-Leh highway is being double-laned at an investment of Rs. 560.81 crores. Again, by debit to the defence expenditures, the BRO is working on upgrading and double-laning the Manali-Leh highway at a cost of Rs. 1335 crores.

At the same time, nearly two-thirds of another 248 km defence road, Nimo-Padam-Darcha, that would offer Leh direct access to Zanskar bypassing Kargil, is almost ready. Buddhist dominated Zanskar, considered as the last surviving cultural satellites of Tibet with its undiluted culture owing to its seclusion and inaccessibility, is part of the predominantly Muslim Kargil district and this road would make it more accessible from Leh bypassing Kargil. Already Rs. 61.72 crore stand spent on the project slated to be completed by 2010.

Interestingly, sources said a feasibility survey is in progress to explore the possibility of linking Leh with Shimla by opening Kibar-Karzok road via Parangla pass.

But Delhi’s most ambitious plan is to have railway connectivity with Ladakh. An initial feasibility survey for a 498-km track linking Leh with Bilaspur in Himachal is complete. It is estimated to cost Rs. 22,000 crores and would be used to ferry 6,000 passengers daily beside a freight of 3.92 million tonnes a year.

All these massive road projects, however, have not impressed Leh much. The people of Leh have an emotional attachment with a historic road linking Leh with Western Tibet. They still see it as a window to the future.

It was only after the opening of Nathu La (Sikkim) for the cross border trade that New Delhi and Beijing formally discussed reopening of another three routes – two in Tawang (Arunachal) and one in Ladakh, in November 2006. India has made almost full preparations at Damchok, Ladakh, the last post on this side, for resuming trade and restoring relations between the people sharing faith, culture and language, after over four decades of separation. Only a culvert on the Damchuk rivulet needs to be laid and things can start. But Beijing does not seem to be much interested in opening the route, at least for now.

Opening of this route would mean Beijing’s resumption of first surface contact with this part of J&K. The Karakoram highway already connects it with Islamabad through Gilgit-Baltistan and since 2005 it is plying a daily bus service between Gilgit and Kashgar, a 12-hours long drive. In the pipeline is a plan to lay a rail-link that would eventually give Beijing access to Pakistan’s Gawadar port in NWFP through erstwhile J&K territories.

Chocked in the chill between the relations of world’s two most populous countries, Ladakh has literally been praying for opening the historic trade route with Western Tibet that got closed in 1962 soon after Beijing’s take over of Tibet in 1959.

In absence of formal trade, the road has become a defence track with severe restrictions on tourist movement. Damchok, the nearest spot to the Sino-Indian border is 330 km from Leh and connected by a motorable road. “There are two major towns very close to the border (the nearest one Tashigang is barely 15 km after Damchok is crossed) and the roads are good and huge and can sustain a better level of trade,” Tsering Dorje said.

The reopening of this road will also address the major demand of the people of Leh that Beijing be convinced to permit Kailash Mansarovar bound pilgrims to proceed via Leh. The base camp for the yatra is barely 250 km from Damchok and the entire road is motorable.

J&K has been aggressively demanding the reopening since 1998 when over 200 pilgrims were killed under landslides at Malpa. The pilgrimage is currently carried out through UP and Uttaranchal using the highly risky, expensive and time-consuming route. “If the road opens for trade, there is no reason for it not being used for pilgrimage,” said a senior Ladakh leader. Apart from being the source for Indus, Brahmaputra, Sutlej and Kamali rivers, the Mount Kailash (6,675m) in Western Tibet is the spiritual centre for four faiths- Tibetan Buddhism, Hinduism, the Jains and Tibetan Bonpo’s.

The Customs department that has been running a Customs Preventive Station (CPS) at Nyoma has “almost finalized” the process of land acquisition for upgrading it to a full-fledged Land Customs Station (LCS). Since the station is 120 km from the Indo-Tibetan border, the department is opening another land customs station at Damchok. They are even considering an LCS at Loma, another place on the same track, in order to prevent smuggling.

The historical Silk Route also runs through the rear of the region. Nubra valley that lies beyond Khardung La pass is barely three hours drive from Kashgar, Khotan and Yarkand – three main centres of the Silk Route.

Tragically, it will be this route that will witness more delay if the cold war continues or takes the worst turn. The other casualty of the standoff would be the Moti Bazaar of Leh that showcases whatever Beijing manufactures. Smuggling will be hit hard and would mean a huge loss of money to some.

Apart from dousing the flames diplomatically, right now the emphasis is to help the herdsmen settle in the remote belts straddling the Actual Line of Control (ACL). Civil authorities have suggested that the government should help the tribesmen to have ‘permanent structures’ instead of temporary ones.

Though in many cases the Changpas were doing it at their own level the PLA would intervene and unsettle them. Revenue officials in Leh revealed that in December the PLA forced five Changpa girls out of a place that Chinese claimed to be theirs. They burnt their grass stocks for winter. Soon after, the PLA uprooted another nomad camp in Skakjung belt. Officials say that Beijing is following a pattern of pushing the nomads towards the hinterland and claiming that part as its territory by raising permanent structures. It happened with Nang Tsang in 1987, Na Kangai in 1991 and Lungba Serding in 1994. On most of the border including the Pangong lake, reports suggest, there is no ‘no-mans-land’ because it has already been devoured by PLA.

The only method of preventing the recurrence is to help nomads have permanent structures and open the areas for visitors. Movement of travellers to forward areas, it is believed, would trigger some economic activity that eventually would settle populations in remote belts. Areas lacking any inhabitation in Leh are vast.