East India Company’s veterinarian and stud manager, William Moorcroft is the most referred author about early nineteenth century Kashmir. While living in Srinagar between November 1822 and December 1823, he remained busy interacting with people, treating and conducting surgeries and documenting life and society. These passages from his biography by Garry Alder offer the precise details of the explorer

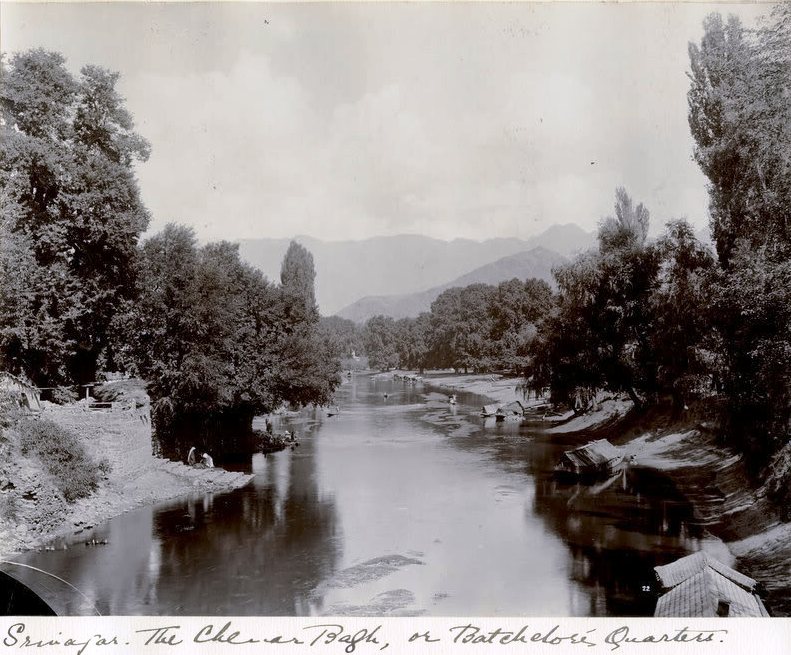

On the afternoon of 3 November 1822, accompanied by Surat Singh and an impressive escort of troops, they entered Srinagar, the crazy Asiatic Vienna threaded with water which is Kashmir’s capital. Its jumbled, jutting timber houses and filthy lanes were thronged with spectators as they passed. They were led through the town to a timber garden-house, standing at the edge of the water in the so-called garden of Dilawar Khan. That little house, put at his disposal by Ranjit, became home for Moorcroft and many of his party for the whole of their stay in Srinagar. Other European visitors were housed at the same spot later. It was comfortable enough and especially welcome when the snow arrived on the floor of the valley shortly afterwards and lingered there till mid-March.

Moorcroft came to believe that the unhealthy atmosphere from the near stagnant water sometimes addled his wits. Certainly, his party was far less healthy in Kashmir than it had been in Ladakh and one of the hapless Gurkha sepoys died soon after their arrival in the valley.

Moorcroft knew that he and Trebeck were the first Europeans to visit Kashmir for forty years. He wanted time to examine the geography and natural products of the valley and report on what he had already seen. It was therefore fortunate in every way that Ranjit Singh so readily granted permission for them to stay.

Moorcroft’s first political despatch to Calcutta from Kashmir was completed just before Christmas 1822. It was more like a small book. In it he returned once again to his old theme, that India was vulnerable to Russia, not necessarily from Persia and the north-west as the prevailing orthodoxy would have it, but from the extreme north by way of Ladakh and then Kashmir. He provided in immense detail the results of his observations along the route from Leh across the Zoji-la, in places giving an almost yard-by-yard and blow-by-blow description of how and where the road could best be defended. At all costs, he argued, the Russians must be kept out of Kashmir. Its mountain walls made it a natural fortress and its fecundity was such that up to half a million men could be fed and provided with every war material.

Even more so if the unreliable Ranjit Singh remained master of Punjab.

Moorcroft even suspected that Ranjit might sell Kashmir to the Russians for cash and that the French adventurers training his army were former Napoleonic agents secretly in the pay of the Russians!

A Sick Kashmir

Moorcroft could find only one consolation in the present situation and, perhaps wisely, crossed it out from the draft of one of his official despatches. Venereal disease in Kashmir seemed to be so rife that any advancing Russian army after the ‘hardship and privations of a march from Toorkistan’ would be speedily incapacitated.

Never in all his life had Moorcroft come across disease on such a scale as he found among the patients who were soon crowding round the door. His laconic list of them is stomach-turning and Trebeck and Guthrie were both seriously shaken. Guthrie was soon busy compounding purgative pills available free of charge to whoever seemed to need them each day.

Moorcroft set aside every Friday to examine his patients, a task which he regarded as a duty but which, he admitted, he found ‘as laborious as it is appalling to the senses of the sight and smell’. Saturday was surgery day. Moorcroft sometimes treated more than 300 poor wretches in a single day, working from early morning till long after dark.’

The results were sometimes startling. To Parry, he explained that: ‘the performance of operations on the horse has given me a boldness in operating on man which, doubtless bordering on temerity, might startle the regular surgeon. The liberties I take are followed by a success which creates surprise even in one, who during the last twelve years has had no small experience in operating on cases which would be considered incurable by discreet practitioners. . . . I feel that many of my patients, if not relieved by me, must sink under their complaints.’

One of these was a ‘poor woman who had for some years been a most disgusting object from a cancerous mass which projected from the right cheek involving both eyelids and the eye itself. The eyelids were taken off, the eye taken out and the woman has got almost entirely well. On the basis of this case alone, Moorcroft’s fame spread far and wide throughout the valley. In due course, it brought before him a labourer, who mutely showed Moorcroft a cancerous growth weighing more than 81b (4 kilograms) which occupied a great portion of the space between the lower end of the breast bone and the navel and adhered to the ribs on one side. Its growth took its rise many years back and the mass was unmovable in any direction.

An hour before he wrote those words he had removed cancer from a man’s neck like a second head. The following day he was going to tackle the first male breast cancer he had ever met. And these, of course, were only a tiny fraction of the many thousands who sought his help. Moorcroft had only one major medical disappointment in Kashmir and that was not his fault. He hoped to introduce vaccination into the valley because smallpox was such a disfiguring scourge there but in every case, as had happened in Ladakh, the vaccine he badgered his friends for either miscarried or arrived from India inert. With this exception, it is clear that Moorcroft’s medical practice brought him immense personal satisfaction. It was also, as he well knew something of ‘a passport of safety’ for him and his party.

The Research

All the same, they had to be continuously on their guard. Shortly before they left Srinagar, a Sikh fanatic drew his sword on Izzat-Allah but was seized before he could cut the man down. At about the same time, a truculent band of armed fakirs had to be driven away from Moorcroft’s door and later shouted insults and threatened violence.

His research extended into antiquities, social customs and ancient manuscripts. At his own expense, he restored the tomb of a sixteenth-century conqueror of Kashmir, who had invaded by way of Ladakh from eastern Turkestan, and he went to immense trouble, and some expense, to enable Csoma to return to Ladakh and pursue his literary and linguistic researches.

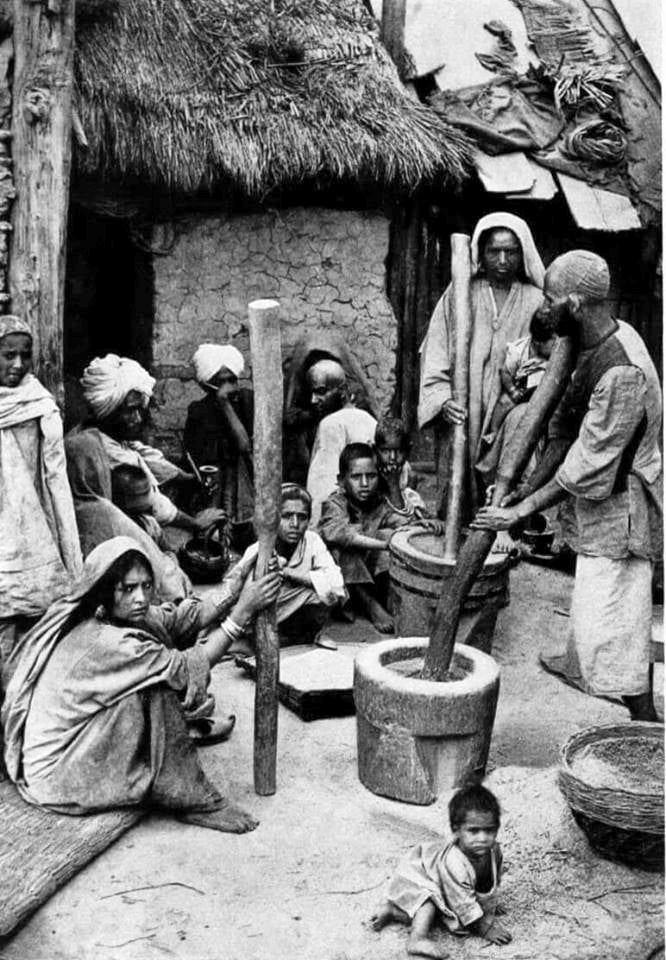

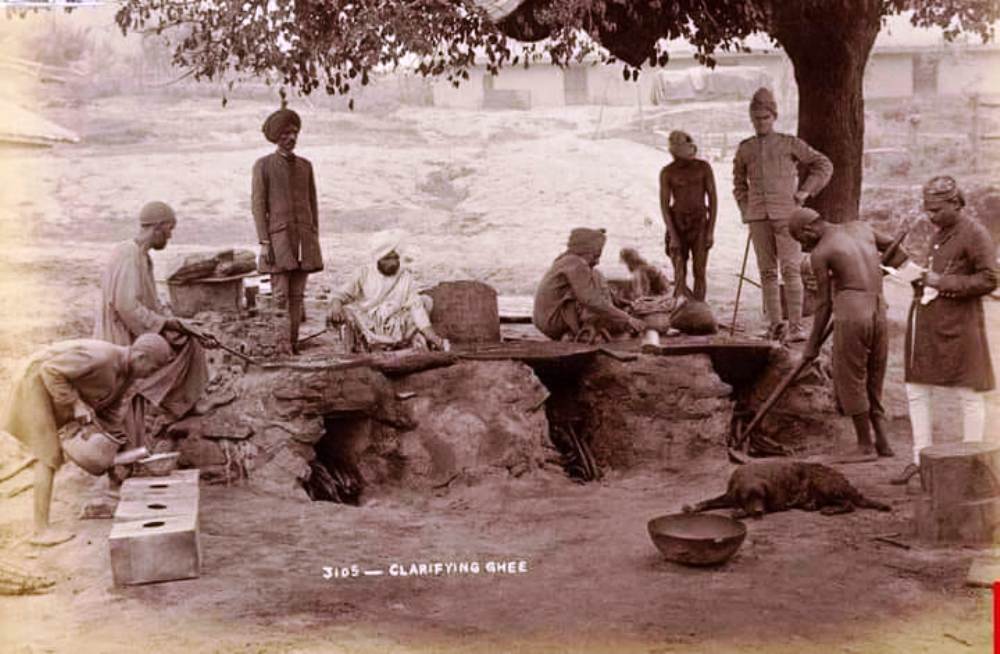

His chief interests, however, were always in anything useful and practical which might prove of benefit in Britain or India. The techniques of rice cultivation and storage, bee-keeping, manuring and viticulture; the extraordinary botany and husbandry of the lakes; walnut, fruit and medical drugs; gun, sword, cotton, chintz, leather and papier-maché manufacture are but a few.

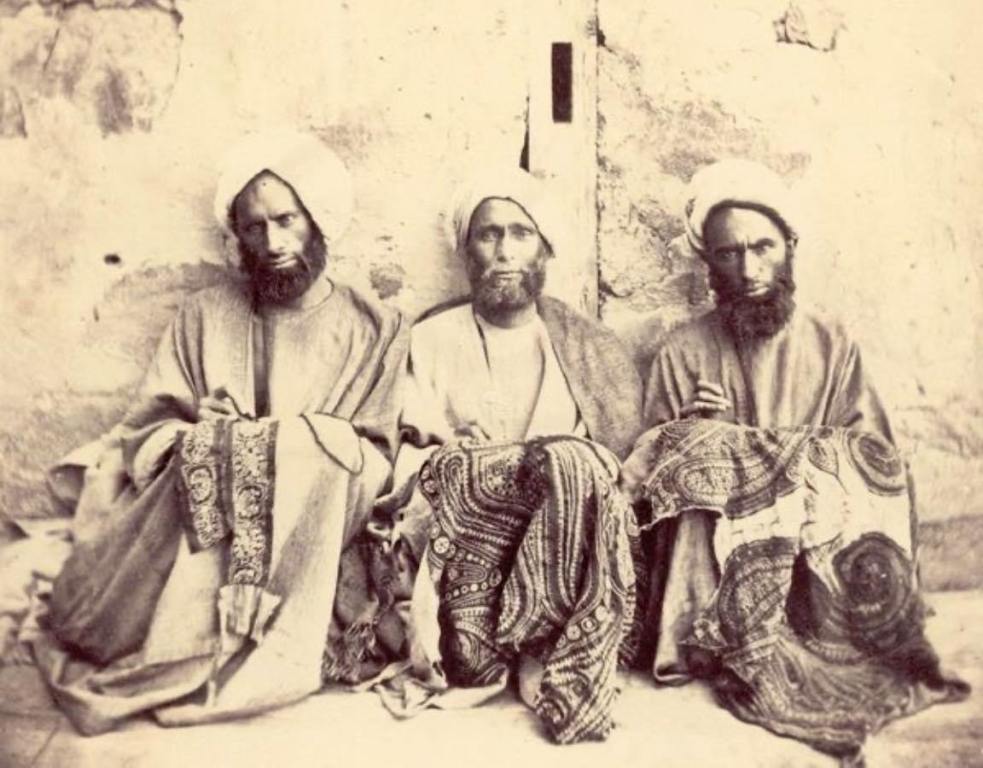

Interest In Shawls

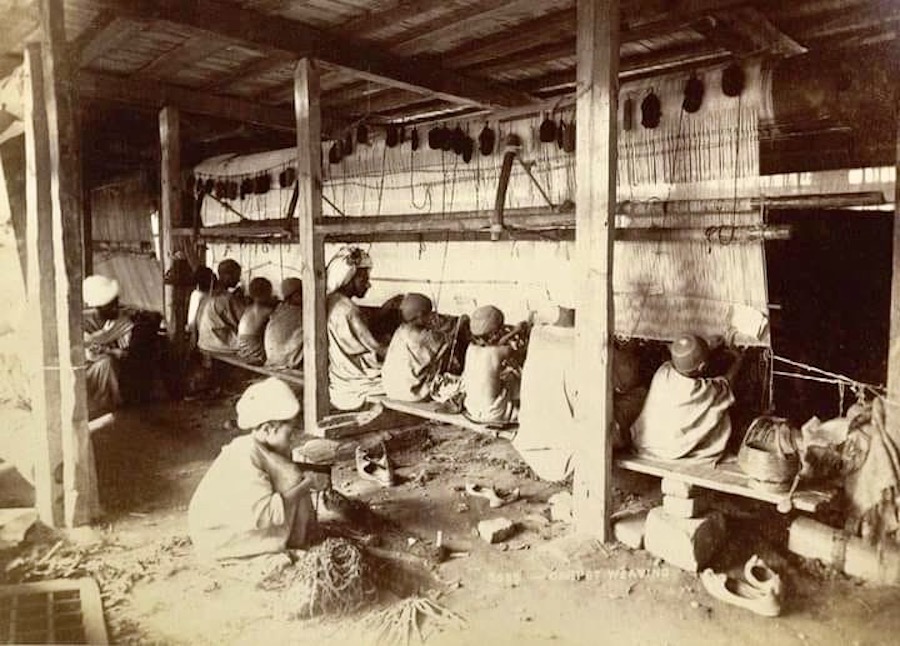

Above all, a sojourn in Kashmir was, for Moorcroft, a unique opportunity to complete the enquiries into the shawl industry, which he had first launched in Tibet in 1812 and pursued avidly ever since. He had inspected the pastures of the shawl goats, had travelled along the high pack-routes along which the wool was carried, had mastered the technique of separating the fine wool from the coarse and now he could examine at first hand the brilliant techniques of the shawl artists and weavers. His writings and samples not only played a key role in the establishment of a British shawl industry but have become a unique and priceless source of information to textile historians.

Moorcroft’s information was not simply the result of earnest questioning. Where necessary he took local experts directly onto his payroll and often into his house. There were twelve shawl-pattern artists and 300 pattern embroiderers working for him at different times. A few of the exquisite gouache pattern paintings he commissioned are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and are of great importance to scholars. Perhaps even more important was the ancient Kashmiri-Sanskrit text on which Moorcroft set ten pandits to work preparing a translation. He also employed a bee-keeper, a musician and four craftsmen. Moorcroft rarely did things by halves, and it makes his own output even more remarkable.

‘I am writing,’ he told one of his aristocratic friends in England, ‘in a small room filled with workmen who chatter in several languages with such a never ceasing clack as renders it difficult for me to keep my attention from them. It all cost much more than merely his comfort and concentration. During his stay in Kashmir, he was depleting his funds roughly twice as fast as his salary was replenishing them. There is nowhere a hint of regret about this in his correspondence. On the contrary, the possibility that his researches would augment what he called ‘the stock of public capital’ seems to have been rewarded enough. He took great care, before leaving Kashmir, to assign the whole of his papers to the government in case anything should happen to him. As well as the flood of information, he sent down to Calcutta twenty-five huge consignments of seeds, samples, routes, drawings and maps, for expert examination in Calcutta and London.

Seeds and Plants

The justification for the journey was, to him at least, self-evident. He had noticed that the timber piles supporting the bridges and houses of Srinagar were untouched by decay even after centuries of immersion in water. The finest deodar trees, he was told, grew on the hills flanking the narrow Lolab valley, just across the ridge to the northeast of the Wular lake. Their introduction into Britain might bring immense benefits. That was sufficient justification.

He would go and collect some seeds. And go he did, first by boat down the Jhelum and across the lake, and then over the hills into the valley. In those days it was a much more wild and untamed place than it is today and when Moorcroft at last arrived, it proved to be sometimes waist-deep in snow.

Measured obstinacy was not always enough. He failed to find any worthwhile seeds and turned back disappointed on 22 December, but once again his medical skills came to the rescue. A nameless village headman, who was also a grateful patient, heard about the problem and set some of his people to work. Soon Moorcroft had his precious pound or two of the seeds in good condition for trials in Calcutta and England. He was back in the little house by the lake on Christmas Eve, just in time for a white Christmas. Shortly afterwards, a splendid dinner with some generous gifts was organized for him and the Muslims of the party by the ever generous Khoja Shah Nias.

Pleasure Parties

It was not really until the April of 1823 that the sun returned properly to Kashmir, and they, at last, began to see the valley in all its famed and iridescent glory of blossom and bird-song, lake and distant snow mountain, alpine meadow and rich forest. This was the traditional time of pleasure and of endless parties among the gardens and islands. ‘Nothing but music and song resounds over the waters,’ recalled old Ghulam Hyder Khan wistfully: “Moorcroft went to three or four parties of pleasure given by the viceroy, Motee Ram Dewan, to the gardens beyond the lakes; most of the trips were performed by water, in those little boats; he had dinner dressed for him, consisting of pillaus and kubabs; and separate sets of dancing women allotted to him for his entertainment.”

The dancing women of Kashmir were particularly accomplished and beautiful, he noted.

Down South

Besides the Srinagar of 1823, with its insanitary houses, filthy streets and choked canals was no place to linger in. As the sun climbed higher in the sky each day, the servants began to go down with fevers one after another. Unfortunately, much of the humming activity in and around the little summer house by the lake was still so incomplete, that Moorcroft and Trebeck decided to take advantage of the delay to make a short tourist excursion to the source of the Jhelum River, on the first slopes under the snow ridge of Pir Panjal. The gardens there, beautified by the Mughal emperors, have not changed much since Moorcroft and Trebeck’s visit. ‘The young and romantic Trebeck was assailed there with bitter-sweet reflections about the passing of greatness and the brevity of human life which were ‘almost painful’. Perhaps it was a presentiment. He had less than eighteen months more of his own short life to live by then.

They all knew that once they left Kashmir and the relatively settled territories of Ranjit Singh for the tribal hills, they would be in a very different world where every man was armed, where life was cheap, where plundering rich caravans had been a way of life for centuries, and where no empire in history had ever succeeded in imposing more than a temporary veneer of law and order on the more accessible valleys. Moorcroft and Trebeck both took the opportunity in the early summer of 1823 to write letters of farewell or send presents to everyone they held dear. They also committed as much as possible of their discoveries to paper, before sending all that could be spared down for safekeeping to the British forward post at Ludhiana.

It is quite clear that ‘considerable and vexatious delays and much anxiety’ accompanied their departure from Srinagar.*? In mid-June, the tents were first pitched at the halting place outside the town, but it was not until late afternoon on the last day of July that the polyglot members of the party, now eighty in number, were safely loaded aboard thirty river boats (the horses and much of the baggage proceeding by land), and set off down the Jhelum.

They were watched by vast and noisy crowds at every bridge and vantage point and, in Trebeck’s words, were ‘not a little troubled by parties of women coming to us in small skiffs and accompanying their application for alms by a song in the full chorus’. Moorcroft missed all this. He was paying his final respects to the Sikh governor up in the great fort-palace on the left bank of the river. He may even have been there watching, as his little convoy passed down the river below. At all events, he did not rejoin them in camp, just north of the town, till after sunset.

Dramatic Exit

For most of the party those early August days of 1823, as they moved gently downstream towards Baramula were unusually restful, apart from the attention of clouds of mosquitoes. Not, of course, for Moorcroft. He left early in the morning on 2 August to make a two-day botanical excursion to Gulmarg. That most lovely of Kashmir’s high alpine valleys, with its green meadows, dark forests and distant views across the valley towards the snow giants, reminded him, as it has reminded countless others of his countrymen down the years, of home. His admiration for the fine cattle and healthy horses he saw there led him, by a natural train of thought, to speculate once more about what would happen to the Punjab and Kashmir when Ranjit was dead. It was a theme which recurred often in his journals and occasionally in his political despatches. His forecasts, at least for Punjab, were surprisingly precise and accurate. That he longed fiercely for a British takeover, so that all the rich potential of these lands could be achieved, goes without saying.”

At Baramula, the Jhelum enters the gorge by which it leaves Kashmir and tumbles down into the Punjab plain. They spent some rather uncomfortable days there ‘writing letters, winding up accounts and adjusting other matters’. The wind blew incessantly; there were signs of trouble from the near-rebellious chief of Muzaffarabad, at the other end of the Jhelum gorge; it looked as though their Kashmiri porters would cut and run at the first opportunity, and Moorcroft was unwell.

At last, on 10 August, they said goodbye to their mentor and friend, Surat Singh, and set off unescorted down the Jhelum gorge. Ominously, the merchants who had travelled under their protection as far as Baramula stayed behind. Moorcroft’s men were little more than a day’s march down that rugged but stiflingly hot river-gorge when they discovered why. About 100 armed men were drawn up across the path in front to enforce what was an extortionate demand for customs duty. After an anxious night under arms, Moorcroft suppressed his instinct to fight and decided to turn back towards Baramula. There were some uncomfortable moments, for they were expecting to be attacked at any moment. Moorcroft stationed himself at the rear and they set off back the way they had come, soon meeting the good Surat Singh and thirty of his soldiers riding hard towards them.

Eventually, in response to his anxious urgings and those of the governor, Moorcroft was persuaded to return to Srinagar for a few weeks. He was not entirely convinced that the whole thing was not a plot, perhaps like many of the earlier delays, to detain them in Kashmir indefinitely for some dark purpose known only to Ranjit Singh. ‘All is crooked with the Singhs,’ he wrote in his journal. At least a short delay would give time, both for the monsoon on the edge of the plains and the apparently widespread anti-Sikh rebellion there, to abate their fury. So it was that they returned to the little wooden house in the Dilawar Khan watched by the same crowds who had seen them on their way just seven days before.

Moorcroft and Trebeck were soon immersed in their various researches and activities. Moorcroft returned thankfully to his medicine and to more investigations into the botany and rural husbandry of Kashmir. On 20 August he was out with Guthrie in the hills behind the Shalimar gardens examining a medicinal root growing there. On the 29th he was inspecting the beehives of one Russool Shah, a humble painter of papier-maché pen-cases. And so it goes on. From 7 September, he was so busy reporting all this new information to Calcutta that his journal stops for a month. By the time it started again, he and his party had left Srinagar, this time for good.

There were the usual irritating delays, of course. If it were not the heavy rain, then it was the colourful Muharram festival; but at last, on 23 September, they headed out across the valley, already lovely in its autumn colours. Instead of striking westwards by the direct Jhelum gorge route to the plains as before, they were persuaded to go on a lengthy detour much further to the southwest. This time, Surat Singh and his men had orders to accompany them all the way. Moorcroft once again left the main party briefly, this time to examine saffron cultivation near Srinagar and a novel means of asphyxiating its rodent predators with smoke. They were soon in the hills that ring the valley and at last, on 30 September, passed over the ridge by the old Mughal road across the Pir Panjal pass.

(These disjointed passages were reproduced from The Life of William Moorcroft, Asian Explorer and Pioneer Veterinary Surgeon, 1767-1825 by Garry Alder, a book published in 1985)