Once interested in an overt role, US off late preferred a hands off approach, or at most a covert role in Indo-Pak tangles on Kashmir. Sara Wani tracks the history of American indulgence vis-a-vis Kashmir.

America has maintained its presence in Indian subcontinent since 1946. It supported the idea of federal India rather than partition. Post-partition, Americans remained opposed to further balkanization of Indian subcontinent and resisted to support the call for a separate state status for Kashmir.

After British left, three issues emerged almost instantly – Junagarh, Hyderabad and Kashmir. Rulers of Junagarh and Hyderabad wished to be part of Pakistan but their Hindu subjects revolted and they merged with India. Kashmir, a Muslim majority state ruled by Hindu ruler wanted to be left alone and from August 15 to October 27 it was a free and independent state. Americans skipped responding even though they knew the emergence of crisis over Kashmir. They chose not to come to Maharaja’s rescue.

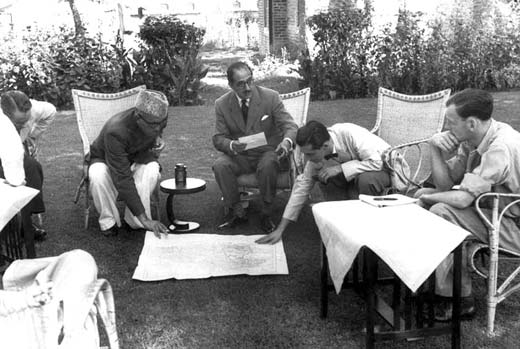

(Photographs taken by legendary French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) in 1948 shows Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, who headed the emergency administration in J&K after 1947, discussing issue regarding the ceasefire line with the members of United National Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP).)

The possibility of a separate state status for Kashmir was brought to American attention in the winter of 1947 when Sheikh Abdullah (as a member of Indian delegation to UN) in a private conversation with Warren Austin, US representative to UN, called for independence from both India and Pakistan. A surprised Austin discouraged Sheikh. America was against balkanizing the subcontinent further to protect its regional interests.

Though Americans toyed with the idea of independent Kashmir yet it was least cosy with it. Washington’s Kashmir policy makers of Truman era George McGhee and John D Hickerson considered independent Kashmir “unviable and dangerous which should be resisted”.

Only two months later, however, the US asked its missions in Delhi and Karachi “not to oppose the idea” if independence appears to be the basis for a settlement on Kashmir. Many think, Americans might have preferred and proffered settlement of Kashmir with reference to people in 1947 itself had Sheikh not retracted from his conversation with Austin in New York to joint Indo-Pak management of Kashmir expressed before US Ambassador in Delhi, Henry F. Grady.

Despite Sheikh’s inconsistent and ambiguous approach US ambassador to India Loy Henderson who succeeded Grady and failed presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson kept meeting him. Even this back channel diplomacy for creating an independent Kashmir came to an end with Sheikh’s unceremonious arrest in 1953. Then, he was the Prime Minister of J&K.

Though Americans toyed with the idea of independent Kashmir yet it was least cosy with it. Washington’s Kashmir policy makers of Truman era George McGhee and John D Hickerson considered independent Kashmir “unviable and dangerous which should be resisted”.

US presidents’ Eisenhower, Truman and Kennedy showed personal interest in settlement of Kashmir issue but failed. In 1961 India was facing Chinese pressure and having no alternative looked up to US for help. The time was ripe to push for settlement but Kennedy failed to persuade Nehru during his 1961 Washington visit calling Kashmir Nehru’s “bone deep issue”.

It was during this era that US ambassador to India John Kenneth Galbraith floated the idea of soft border between J&K and Pakistani administered part of Kashmir. While India and Pakistan would retain territorial claims on their side of Kashmir, he suggested, they would allow free movement between the two sides. Nehru was positive as the solution allowed him to retain the territory. But the idea was not pursued because it did not go well with Pakistan.Americans were in South Asia to contain communism but when China came crashing at Indian gates they came to its rescue with military and diplomatic aid much to the chagrin of Pakistan. Kennedy even directed Ayub to keep its hands off Kashmir during the conflict, assuring him of concerted efforts his side would make to seize this “the fleeting…one time opportunity” to settle the Kashmir issue after cessation of Sino-Indian hostilities.

It was during this era that US ambassador to India John Kenneth Galbraith floated the idea of soft border between J&K and Pakistani administered part of Kashmir. While India and Pakistan would retain territorial claims on their side of Kashmir, he suggested, they would allow free movement between the two sides. Nehru was positive as the solution allowed him to retain the territory. But the idea was not pursued because it did not go well with Pakistan

The promise was spelled into action on ground and Nehru was forced to enter into talks without preconditions with Pakistan.

During these talks Galbraith suggested inclusions of Kashmiris’ into the negotiating process for the first time. Then, Kennedy administration was working on a plan envisaging division of Kashmir. It wanted an international border to run through the valley. The plan was supposed to be tabled if the two governments failed to reach any agreement on their own. Then, UK was supportive of internationalizing Kashmir. But nothing came out of the four rounds of talks.

USA blamed China for jeopardising talks by publicizing the recently concluded Sino-Pak border agreement involving Kashmir. It admonished Pakistan, privately, for making the pact public deliberately. Whatever was the reason and whosoever was responsible talks failed sowing seeds of anti-Americanism in the region.

US Pakistan relations saw deterioration with the breakdown of 1962-63 talks between India and Pakistan. After Kennedy’s death, Johnson administration decided to limit its involvement in Kashmir issue and the relations between the two countries witnessed further downward spiral as Johnson cancelled Ayubs’ forthcoming visit to America. To balance the things and show Washington’s displeasure then Prime Minister Lal Bhadur Shastris’ visit was also cancelled.

Phillips Talbot, an assistant secretary in State department recommended secret diplomacy for Kashmir settlement. His visit to South Asia in 1964 created much speculation and media in India and Pakistan reported that he had come with a ‘Talbot Plan’. The plan was presumed to be envisaging creating autonomous entity comprising Valley and Pakistan administrated areas of the state with Hindu and Buddhist majority areas remaining with India. But US Embassy dissociated itself with the concept.

‘A plague on both your houses’ as ambassador Howard B Schaffer, called it in his book The Limits of Influence: America’s Role in Kashmir, approach remained dominant Washington’s’ South Asia policy during 1964. Washington’s non interventionist approach was marked by a brief pause when it rebuffed Indian moves to integrate Kashmir into India Union in December 1964 refusing categorically to accept any unilateral settlement of Kashmir issue. Then India’s Home Ministry started the process of integrating the state into the union using Article 370 as a tunnel and doing away with the symbols of autonomy like Prime Minister and Sadr-e-Reyasat and extended the jurisdiction of many of its institutions.

But US’s non-interventionist policy proved brief when fighting broke out in Rann of Kutch in 1965. Not willing to get involved it asked UK to effect a cease fire and manage its settlement – an ‘outsourcing’ that failed.

Then US ambassador to Pakistan McConaughy recommended a warning to India that any aggression in Kashmir would warrant US military intervention as Pakistan is an alliance partner. State Department ignored the idea.

With mounting tension on ceasefire line Washington preferred to involve UN secretary General U Thant and British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson. Indian Army marched to Lahore in September 6, 1965 and Pak foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto handed a memorandum to McConaughy calling for fulfilment of US-Pak bilateral security agreement of 1959.

US rejected the demand saying that Pakistan was not victim of Indian aggression. Instead, it assured Pakistan that US would refer matter to UN and would vote in their favour in Security Council. Pakistanis were rebuffed for using military assistance meant for communist countries in the region in Kashmir. Though Secretary Dean Rusk advised intervention to bring about cessation of hostilities but Washington preferred not to get involved unilaterally. Johnson administration behind the scene devised UN strategy to tackle the problem, that too not for Kashmir but to save “Western power position” in the region.

During the whole crisis Pakistan pressed for right of self determination for Kashmiris as quid pro quo for cease fire. Fearing Ayub Khan might seek Chinese help Washington warned him of dangers such move may cause to the bilateral relations of the two countries. Ayub did respond by claiming that he has discouraged Chinese involvement but he was truthful. Pakistan agreed to cease the hostilities as international pressure mounted and China refused help and started seeking assurance from Johnson administration for honourable settlement of Kashmir issue but no assurance came forth.

US even refused to broker a peace agreement as US secretaries McGeorge Bundy and Robert Komer recommended non-involvement. They thought that any US involvement at this juncture would become cause of further trouble with India and arouse false hopes in Pakistan. Washington left the field wide open for Moscow which was pleased to step in and facilitate peace agreement in Tashkent. Washington was much pleased to pass the buck and see Moscow frustrated. Pre-occupied with Vietnam, Johnson administration deeply felt that Kashmir issue least deserved the attention it was being paid as both India and Pakistan had outlived their value for Washington’s cold war strategy by hugging region’s communist powers.

Indo-Pak war of 1971 forced Washington to abandon its escapist policy. President Nixon upset at CIA reports that India was going to ‘liberate southern parts of Azad Kashmir’ sought assurances from Delhi against that. Americans were much pleased when at the end of war and dismemberment of Pakistan, both countries decided to put Kashmir issue into cold storage at Shimla.

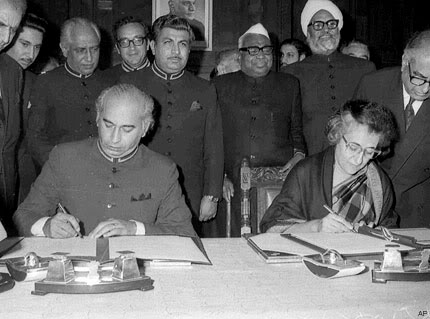

(Zulfikar Ali Bhtoo and Mrs Indira Gandhi signing the Shimla agreement.)

The Shimla Agreement became a reference point and successive regimes in Washington followed Johnson’s hands off approach till outbreak of insurgency in Kashmir in 1989 took Washington by surprise. They were shocked by the mass support the armed rebellion against India enjoyed. Kashmir did receive attention during Bush and Clinton eras but Indo-Pak nuclear programme and Afghanistan remained high on their South Asian agenda. Washington woke up to the reality of yet another Indo-Pak war as India started blaming Pakistan for its troubles in Kashmir and started troop deployment along the LoC. US ambassadors to India and Pakistan Robert Oakly and William Clark called the uprising spontaneous.

While involving Moscow and Beijing in diffusing tension and managing crisis, Washington remained preoccupied by sending its Deputy National Security Advisor, Robert Gates to New Delhi and Islamabad for making ‘accurate and realistic appraisal’ of the situation. Those were the times when Pakistan had lost its value as a front line state in Afghanistan as Soviets had retreated, Pakistan feared that Washington would abandon them as it had done in 1965.

Gates admonished Pakistan for supporting insurgents and warned them not to expect US intervention if a war breaks out.

In India Gates was friendlier and advised Indians to improve their human rights record in Kashmir, the policy they employed during early years of insurgency amid occasional demarches. A few Congressmen including Dan Burt called to cutting off Economic aid and military training to India for her poor human rights record in Kashmir. They won majority support in the house but not the concurrence of the Senate.

As situation in Kashmir worsened, US again made a call for ‘taking wishes of Kashmiri people into account’. This fuzzy language and ambiguity departed when new Assistant Secretary of South Asia in the state department, Robin Raphael took charge and made US stance more clear by saying that the US views ‘whole of Kashmir a disputed territory, the status of which needs to be resolved’. She said that US does not recognise the instrument of accession as meaning that Kashmir is an integral part of India.’This triggered a concern and anger in New Delhi.

Despite this stance and Clinton’s publicly expressed concerns over human rights violations in Kashmir, US chose to get involved if both parties to the dispute agreed to. Though it extended offer of mediation Washington disappointed Pakistan when the latter submitted a draft resolution to the United Nation Commission for Human Rights calling for dispatch of a fact finding mission to Kashmir by refusing to vote along-with other Western countries, if resolution was brought to vote.

After initiation of political process in Kashmir, elections were held in 1996. Welcoming the process US maintained that though the elections were no solution yet may provide an ‘opportunity to begin a real dialogue between India and Kashmiri people’.

Pakistan again tested US’ seriousness in resolution of Kashmir palatable to them in 1998, when India conducted nuclear tests by threatening to follow suit. Feeling the heat Clinton administration dispatched a high level team led by Deputy Secretary Strobe Talbott to Islamabad to dissuade them from conducting the test. Pakistan in response asked them to effect a Kashmir settlement that would be satisfactory to them as quid pro quo, but Washington washed its hands off, perhaps knowing fully well that it lacked power to persuade India for one time settlement of Kashmir favourable to Pakistan. Instead they offered economic and moral aid besides presidential invitation to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif for an official visit to US.

When Talbot mission failed and Pakistan conducted tests, US made fresh efforts and even brought about UN resolution to make India and Pakistan to resolve all pending issues including Kashmir. The move forced Vajpayee to visit Lahore in early 1999 where he held cordial meeting with Nawaz Sharif. Both leaders declared that they would ‘intensify their efforts’ to settle Kashmir but Clinton wanted both countries to move forward and take concrete steps to resolve it.

Rebuffed by Chinese as Ayub was in 1965, Sharief asked for US brokered Kashmir settlement, Clinton refused to get involved until Pakistan withdrew from Kargil. He even turned down Sharif’s request for a face to face meeting with him. Sharief nevertheless came calling uninvited. Subsequent meeting with the two leaders could not fetch him anything beyond a lecture on ‘restoration of sanctity of control line’.

A year later, however, Kargil crisis changed the situation. Fearing worst, US reinforced its diplomatic efforts to defuse the crisis. America asked Islamabad to withdraw from Kargil refusing to buy Pakistan’s official line that Kashmir insurgents were acting on their own and publicly asked it to ‘respect the LoC’. Rebuffed by Chinese as Ayub was in 1965, Sharief asked for US brokered Kashmir settlement, Clinton refused to get involved until Pakistan withdrew from Kargil. He even turned down Sharif’s request for a face to face meeting with him. Sharief nevertheless came calling uninvited. Subsequent meeting with the two leaders could not fetch him anything beyond a lecture on ‘restoration of sanctity of control line’.

Post Kargil American Kashmir policy saw a sea change, redrawing of borders seemed out of question, while redefining India-Pak-Kashmir political relations was in focus. After 9/11 Pakistan came under heavy pressure to end its support to Kashmir insurgents and the events like suicide bombing of state assembly and attack on Indian Parliament escalated tension and troop movement on the borders putting Pakistan in dock. Bush administration refused to play a mediators role and instead favoured Delhi-Srinagar dialogue and conduct of free and fair elections in the state. America’s veiled appeals to Hurriyat to participate in elections were a sharp shift in its Kashmir policy. At the same time it encouraged back channel un-publicised process for settlement of the issue with out getting involved.

The process seemingly met with success when India and Pakistan decided on some CBM’s like allowing cross border trade in Kashmir.

The process seemingly met with success when India and Pakistan decided on some CBM’s like allowing cross border trade in Kashmir.

While doing so, US ensured that they make a distinction between moderates and the hawks in Kashmir’s separatist camp. Never ever after that has any US diplomat met Syed Ali Geelani. In fact, US state department asked its Islamabad mission to neutralize any support that Geelani might be getting from Pakistan at the political level. It was that situation that left the ailing Geelani almost equidistant from New Delhi and Islamabad during the peak of Musharaf era. His application for a visit on medical grounds to US was rejected by US embassy after a prolonged interview (pre-requisite for visa) with him.

The situation, however, took a new turn as US continued its zero-sum war in Afghanistan. At the peak of his campaigning, Barak Obama talked of giving special attention to the South Asia including Kashmir. He has been strongly advised by his advisers that routes to manage Afghanistan and Pakistan essentially pass through Kashmir. That was why he chose to have a special envoy for the region. But New Delhi’s effective lobbying managed to get Kashmir out of Hoolbroke’s mandate. Security experts in US still believe that addressing Kashmir is a must for stability of the region. There is absolutely no possibility of Obama making his “interventions” overt. But will there be something that would cook behind the curtains?