The Christian missionaries had to fight a despotic ruler, a superstitious society and a looter bureaucracy for a long time before they succeeded in making basic schooling possible in Srinagar late nineteenth century, read from Tyndale Biscoe’s writings

Although the arrival of the Rev J Hinton Knowles in 1880 really marks the foundation of the school, the Rev JS Doxey had got together five boys to whom he imparted instruction. He taught them elementary science in his own house, and also in a room set aside by Dr Edmund Downes in the hospital. He used to take the boys for walks with him and explain to them the movements of the solar system and at night time teach them about the stars. While supervising building operations in the hospital compound, he was able to give them practical lessons in mathematics. About two years later he left Kashmir, and the Rev JH Knowles, with this nucleus, started the school.

At first, the opposition was very strong against the school, and all sorts of efforts were made to smash it. One of the pupils, having been seriously ill with typhoid, was of course weak from after-effects. Mr Knowles, therefore, kindly lent this boy his own horse to ride to and from school. As soon as this fact became known tales were spread that the boy was a convert, and pressure was brought to bear upon his parents to take him away from the Mission school, while the State school offered him a post as a teacher.

This boy, after being a short time in the State school, left it and returned to his old school.

At another time three old boys, now living, were imprisoned for learning English. At least, that was the charge brought against them, though of course, the real reason was to dissuade boys from coming to the Mission school. It is interesting to know the way these boys were caught out. A certain official became friendly with them, and finally asked them into his house, where he showed them a paper on which was some English writing; the boys read the paper and they fell into the trap. On another occasion a master with a party of boys spent a night in the lock-up; as they were leaving the polo ground one afternoon, after a game of cricket, they were seized and marched off for spoiling the turf! Only through the efforts of Mr Knowles and Dr Arthur Neve, through the British Resident, were they released.

Years later one of these boys, who had grown to manhood and whose sons were reading in his old school, stood out against persecution when officialdom arrayed itself with the forces of Theosophy and Mrs Annie Besant to smash the school. Men were going round to the parents of the boys urging them to take their boys away from the Mission school, and threatening them that their boys would never get State employment if they stayed. In this way, they came to this old boy, who had started a boat-building business for his living. When he was threatened with this awe-inspiring loss of career for his two sons he replied, ‘That’s all right, I have no intention of their going into State service, they will come into my business with me.’ However, this is a digression.

By 1885 opposition had so far died down that Mr Knowles was able to leave his room in the hospital and take a separate house for his school, overlooking the river Jhelum. Five years later there was yet another move, and finally, after a third move, the school took up its present abode in a merchant’s house, right in the heart of the city.

Some years later, when the Rev CE Tyndale-Biscoe was in charge, the pressure was brought to bear upon the three owners of the house to turn the school out. This would have been most inconvenient, so the Principal pretended that he had really been intending to turn out in any case, and let it be known that he was going round looking for another site. This, however, failed to impress the ‘three wicked uncles,’ as they were called, for their nephew, who is the present landlord, was then reading in the school. So the Principal thought of a plan as follows:

He felt pretty sure that the landlords were not really anxious to turn the school out, and only needed a little persuasion to allow it to remain, so that they might have an excuse to give to those who were trying to force their hand. At that time the Principal’s cousin, Mr AB Tyndale, and his brother-in-law, Rev CLE Burges, were helping him in the work, one with carpentry and the other, being a wrangler, with mathematics. He asked them if they would come to help him to persuade the ‘three wicked uncles,’ but they pleaded ignorance of the language. ‘Never mind,’ he said, ‘simply do as I do and look as I look.’

A day was fixed for the interview between the three Englishmen and the three uncles. The Principal, with his two supporters, went round to the landlords’ house. On arrival, they were told that, unfortunately, the three uncles had had to go out.

‘We will see about that,’ said the leader of the expedition, and, followed by the other two, he ran upstairs, and there found the ‘three wicked uncles’ seated on the floor. They at once got up and ordered chairs to be brought for the sahibs. The leader sat down, and his two friends sat down, then he began by talking pleasantly and the other two looked pleasant. However, the uncles refused to budge from their decision, so the leader began to argue and look pained, whereat the others looked pained; then he began to look stern, and then he stood up and looked angry, the others copying him in every look and action. Suddenly he thumped his fist on a table, and two other fists came, thump! thump! ‘Hi diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle, the cow!’ he shouted, with the other two following in chorus.

That was enough; at the united roar on the word ‘cow!’ the uncles capitulated, and besought the Principal not to move his school; they had got their excuse, and were only too glad not to lose a good let. Hence the school still stands where it did.

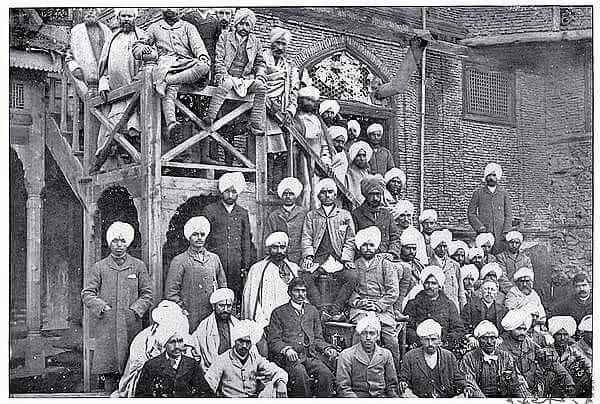

During the early days Mr Knowles had started the boys on cricket, which they played, wearing all the regalia of a Kashmiri pandit of those days tight bandage-like pugaree, golden ear and nose-rings, wooden clogs, and the long nightgown garment, reaching from neck to ankles, called a pheran. This nightgown incidentally came in most useful for stopping and catching balls. Mr Knowles also started the boys with physical exercises, and installed the parallel bars and horizontal bars. But the authorities got to hear of this, and, thinking these exercises smacked of low caste manual labour and that it was derogatory for boys of such high estate (for they were all Brahmans) to be taught such things, drilling was forbidden by order of the Maharaja.

When starting a school where opposition is strong, there are two courses open. The first is in all ways to try to conform to the wishes of the public, so as to induce them to send their sons to school. The second course is to run the school on the lines that are considered to be the best, whether in accordance with public opinion or not; to chance the consequences of getting few pupils, but also to know that those few will get greater benefits.

Both these methods were tried in this school. In its early stages, when the opposition was very great, it was run exactly like any other school in the country, the only objectionable feature being that there was compulsory Christian instruction. But even this objection did not prove so very serious, for many of the boys considered it a good opportunity for practising English, while the more prejudiced let their minds wander.

Apart from this, there was little or no discipline. The Kashmiri pandit is by nature studious, he has no idea of ‘ragging,’ which is the cause of so many scrapes in an English school; and, as punctuality was not insisted upon, there was never any need for disciplinary action. In fact, the cursory observer might have considered them a model set of boys.

The Kashmiri boys liked lessons and hated athletics, and, since the latter were not compulsory, there was nothing in the school to rub them up the wrong way, hence no need for discipline. The school was due to start at 11 am as a rule, but it was seldom that all the staff had assembled before mid-day – for, going on the principle that the East hates to be hurried, it was necessary to pander to this little whim.

The boys learnt their lessons according to ancient custom: all the boys reading aloud in a monotonous sing-song, drawing in their breath with a sucking noise, just as if they were drinking soup, rocking their bodies in rhythm the while, what time the master reclined at ease at his desk.

At this time the boys (many of them being 20 years of age or more) were all Kashmiri pandits (high caste Brahmans), who all wore the regulation dress mentioned previously. The disadvantages of this dress were many. The pheran inhibits any violent exercise, it was commonly worn day and night for weeks, becoming dirty and a harbour for all sorts of diseases. The clogs again prevented any swift movement, also, since it was the universal custom during the winter to carry fire-pots under the pheran, clogs were a source of great danger, causing the wearer to trip up, while the pheran, which was usually worn with the arms inside, the sleeves being flung over the shoulder, served as a very useful trap to hold him down in a sort of sack-full of live charcoal. The nose-rings and ear-rings, being often very heavy and elaborate, caused sores to form, and prevented any attempt at cleaning the affected parts; pocket handkerchiefs were of course unknown. Later it will be seen how one by one these ‘badges of gentility’ were removed, and a more serviceable dress instituted.

Though these methods may seem very slack, and a curious way of running a school, still it must be borne in mind that things were only at the beginning, opposition was great, and it is probable that only by going slowly at first could the school have ever been started, or the public gradually educated to new ideas.

The following extracts from notes written by visitors at that time will show that they recognised the value of the school and what it stood for:

Lord Robert’s, when Commander-in-Chief of India, visited the school in May 1889, and wrote: ‘Lady Roberts and myself were very favourably impressed by the appearance of the pupils generally. Mr Knowles and the ladies who are assisting him to deserve every credit for the satisfactory manner in which they are carrying on the work of education under considerable difficulties. We beg to offer him our congratulations and to express the hope that he may in time be able to extend his work throughout Kashmir.’

Col Parry Nisbet, the British Resident in Kashmir, whom we remember on account of his determination and energy, which resulted in the building of the road into Kashmir, was a firm friend of the school in its early critical days. He writes, after a visit in 1890:

‘There was a much larger attendance of pupils than I expected to see. The neat appearance and remarkable intelligence of the boys was very satisfying. The slight examination I held of several of the classes was sufficient to show that solid and valuable instruction in English, Sanskrit and Urdu is given. I trust the excellent work begun by Mr Knowles may go on and prosper.’

When Lord Lansdowne, the Viceroy, visited Kashmir in 1891, in a speech to the school he expressed pleasure at hearing that the boys were taking to ‘manly sports and exercises,’ and urged the boys to copy Oxford and Cambridge, and learn to ‘pull an oar, or rather work a paddle.’ As will be seen in course of time, the boys learnt to take pleasure in both these sports. Lord Lansdowne made a point of warning the boys against learning ‘your lessons by heart to repeat them like parrots, without considering the meaning and real drift of the words which you are learning.’ In a later chapter is explained how the school tried to follow his excellent advice in this matter as well.

About 1891 the policy of the school was changed, and instead of giving in to all the popular demands, it was decided to model the school on those in the West, where the authorities decide on all matters of school management and do not take their orders from the students. For example, take the matter of holidays. There were no regular school holidays, but instead, innumerable gods’ days and goddesses’ days were given. One never could tell whether all the school or only half, would be present on any given day; for some boys would think one god important and some another. How could there be discipline when boys could attend or stay away at their own whim? So gods’ days had to go, and one by one they were suppressed by the simple expedient of fining boys who stayed away from school. In their place regular holidays were instituted, so that staff and boys could get a few consecutive weeks of rest and change, as in Western schools.

Of course, there was opposition to this change on the grounds of religion, as there always is when any innovation is introduced. But, as again, always happens when a firm line is taken, opposition dies and terrible innovation becomes one of the unchangeable customs.

Holidays were mentioned as an example. But when the policy of the school was changed it was evident that it was not a matter of altering or patching up, but that the whole structure would have to be broken up, the rotten part cut out.

Boys were no longer canvassed to come to school, but were advised when they applied for admission to go elsewhere or bear the consequences of coming to a school which imposed these five conditions:

(1) Compulsory Christian teaching.

(2) Compulsory games.

(3) Compulsory swimming.

(4) Compulsory fees.

(5) Corporal punishment for misbehaviour.

No other school imposed, or ever had imposed, such conditions, and yet the membership of the Mission school went up. What was the reason for this? The reason was the same reason, ultimately, which had caused the policy of the school to be changed. The reason why the boys came was that English was taught to them by Englishmen (for by now it was no longer illegal to learn English). The reason why they wished to learn good English was to get good employment in the State, where pay was small but chances for loot great.

If they could speak better English than their fathers, they could become even better looters. The policy of the school was changed because it was not considered that the result of a Mission school training should be the production of more clever scoundrels than there had been previously. So that the teaching of English brought more scholars who came for a purpose which was not desired, and that in its turn brought about a change in policy.

The policy was, somehow or other, to turn these high caste conceited Brahman sons of the ruling class into men. Men in the true and best sense of the word, who would go into State service in order to serve their State and not simply for what they would get out of it.

The rest of this story will show each phase in the struggle of putting manhood into the Kashmiris, through the past fifty years up to the present day.

In reading these accounts one should bear in mind that, for all their faults, the Kashmiris have good qualities, but for which the story of the school would be very different.

Mention has been made of their sense of humour. Over and over again, things have been made easier as soon as the boys had been given the gift ‘of seeing themselves as others see them’; for the Kashmiris can appreciate a joke, even against themselves.

Through the centuries of oppression under ruthless conquerors which preceded the Pax Britannica, on account of which the Kashmiris had lost their self-respect and manhood, they had developed a wonderful cheerfulness under difficulties. Many a time, under conditions unpleasant enough to make a saint swear, the Kashmiris will start cracking jokes or singing to keep up their spirits.

Also, like that other persecuted race – the Jews – they have developed a stubbornness for their traditions. Once this stubbornness is directed towards sticking to what they know to be right and true, their allegiance to the new tradition is as firm as it was to the old.

Among the old traditions that are dying out is a strong belief in the ill-omen of sneezing. Any orthodox person who intends doing anything will desist if he should sneeze, or hear someone else sneeze. Nowadays small boys, seeing a venerable pandit of the old school coming out of his house for a walk, will go past him and sneeze; at once the old man will hurry home, to come out again a few moments later for another try. He has hardly gone a few paces before an accomplice of the first boy goes past him and sneezes. ‘This is most annoying,’ says the old man, as for a second time he is forced to return; so it goes on, till the last boy of the group has had his sneeze, and the old gentleman can set off on his journey with a light heart.

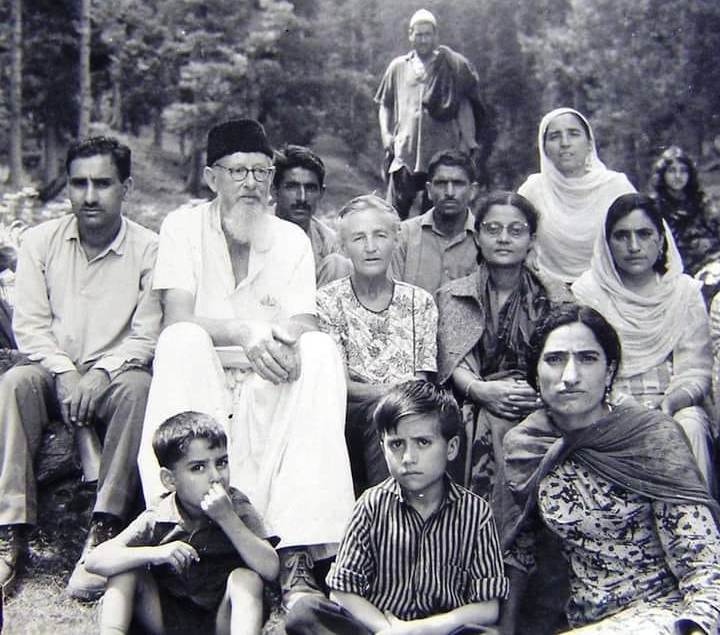

(Excerpted from Fifty Years Against The Stream: The Story of a School in Kashmir (1880-1930), by ED Tyndale Biscoe, first published in Mysore in 1930)