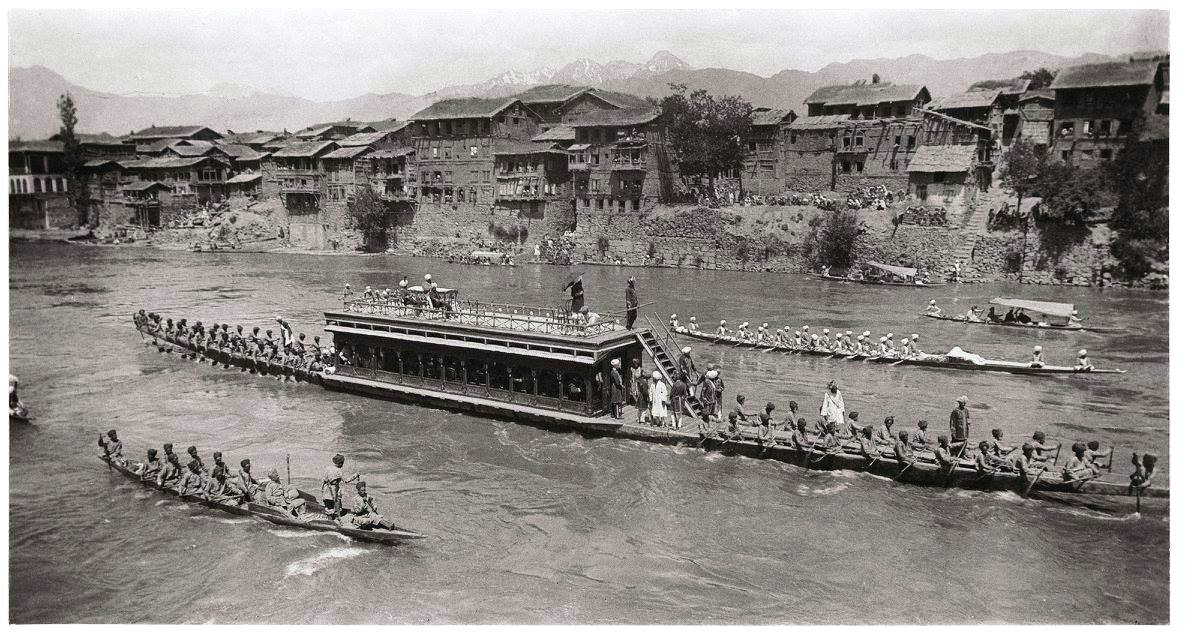

The trek to Gilgit is etched in Kashmir’s psyche because of the Beagar envisaging capturing of young Kashmiris and forcing them to take supplies on their backs from Srinagar to Gilgit. It was forced labour that ended a few decades before the partition in 1947. The trek was a dangerous one as it moved from Srinagar to Bandipore crossing the Razdan Pass and then a steep ascend to the 4100 meters Burzil Pass to reach the periphery of Gilgit.

In the fall of 1911, a wealthy German mill-owner’s son Otto Honigmann crossed this pass to reach Baltistan. His protracted stay in the region, during which he clicked a number of photographs, led his grand-daughter, Dr Michaela Appel rediscover the journey, curate the written and visual records and publish the book Kashmir Ladakh Baltistan, 1911/1912: Photographs by Otto Honigmann that was published by Museum Fünf Kontinente in July 2018. It carries Honigmann’s letter and photographs. She later brought the photographs to Ladakh for an exhibition to help natives revisit their history.

Here follows a detailed letter that Otto Honigmann wrote his mother on November 4, 1911, after crossing the Burzil Pass, which now falls on the other side of the Line of Control. The celebrated German photographer chose to cross the perilous pass weeks ahead of the massive snow, making it impassable and not summer when the forced labourers would be abundantly found everywhere

I have just had a particularly difficult winter encounter, and namely with the Burzil Pass. I can not quite remember whether I wrote in my last letter that this pass still lay ahead, but anyway, soon after that, terrible driving snow set in overnight at the Peshwari Bungalow, so much so that the next morning it lay a foot high, and the pony fellows didn’t want to carry on.

But I pushed on to the Burzil Bungalow, this side of the pass, and found even more snow up there. Together with Hassan Butt, my chief hunter, I decided that we would try it after all the next day. Unfortunately, one of the pony drovers showed signs of near insanity, and I had to take him into my own room not to distress the others. He was calmer in my presence, dried his clothes in front of the fire, so I sent him back to his colleagues.

It snowed a bit more that night and turned colder, the sky clear. But the following morning there wasn’t anything to be done with these pony people from Bandipur. The mad one had beaten himself and was talking absolute gibberish; they all wanted to go home. Now I had to quieten down the mad one again, so I took him back to my room and tried to get some brandy and a couple of aspirin down him to make him sleep. But he was just too restless and would not lie down. I had to smile at the situation I was in; here I was, caring for someone deranged, (I had despatched all the others because they kept on repeating things like ‘He will die here and we will die, too, the same way.’) just ahead of a pass that was, for the time being, impassable, without any reasonable help (early that morning, I had actually sent the two hunters to the coolie villages ten miles below!). It was unfortunate that my cook felt bound to claim that he knew all about these health conditions, that the chap was bad and would probably die. Well, it actually got better and around midday the sick man had calmed down a bit, and I had made the decision to send the ponies and their capable owners back and to go down myself as far as Minmarg, five miles away, in order to send a telegram from the Naib Tahsildar in Gurais, requesting 25 coolies.

The pony drovers were paid (this cheered them up no end) and I gave orders for them quickly to make their animals travel ready, the mad one still showing a little resistance but eventually getting proudly seated on one of his four ponies, and we moved off down into the valley, the eleven ponies ahead of me.

The further we went, the worse the path. The snow was melting fast in the cheering sunshine. Just before reaching the telegraph office, I broke away from the others. The mad one had conducted himself quite well, so I was able to have him led along without fuss. Then I handed in my telegram for more coolies and awaited the answer in the company of the kindly officials, an Englishman and a Eurasian.

I was given a cup of tea and we conversed. At half 4 my hunter, Hassan, came back with a man who explained that he wanted to take me across the pass the following day with eleven capable ponies. It seemed to me highly improbable that I would get the 25 coolies quickly enough, so, after much persuasion by the telegraph officials, who knew this man, I happily accepted this offer and sent an appropriately worded telegram to the tahsildar.

At 5 we all set off for Burzil Bungalow in good cheer, the new ponies and their drovers, my hunters and I. But on the way a fresh snowstorm blew in and lowered our mood a bit on the five mile climb. It was dark when we got there around 7 and the snowstorm persisted. Charming prospects for the next morning! But everyone seemed capable and in good spirits.

The night was cold and we had an early start. The snow had stopped falling and the sky cleared. As many of us as possible forged ahead on foot in order to beat a path for the pack animals. It was a hard climb upward through snow one metre deep, with severe drifts in many places. We covered two miles like this in three hours and had to turn back in the end because we encountered quite a few places where the previous day’s warm weather had caused some minor avalanches to block the path.

It was fine for us comfortably to get across this because the snow had frozen and withstood our weight, but once the ponies walked into the snow, they could go no further. They were in right up to their bellies and could barely move. This meant turning back because the beaten path used by the ‘mail-runners’ was steep and not passable for pack animals. So, back we went!

Luckily the sun came out and the sight of the heavenly snowy landscape comforted me in my despondency so much that I paused to consume my breakfast there and then. We are always battling nature and her challenges and yet at the same time it is her very magnificence that brings comfort and reward, and therein lies the appeal. So I went back to the familiar bungalow, sent the ponies home and the tahsildar in Gurais a new request for coolies by telegram.

The afternoon was very pleasant and I passed it in reading and writing at the Burzil rest house. The following night was clear and cold (8-10°) and a tidy gale blew down from the pass. The next morning a messenger brought me the news that 25 coolies were on their way. Thanks to the news brought by this man, I felt calmed and got another hour of sleep. After luncheon I went down to the telegraph office once more myself […].

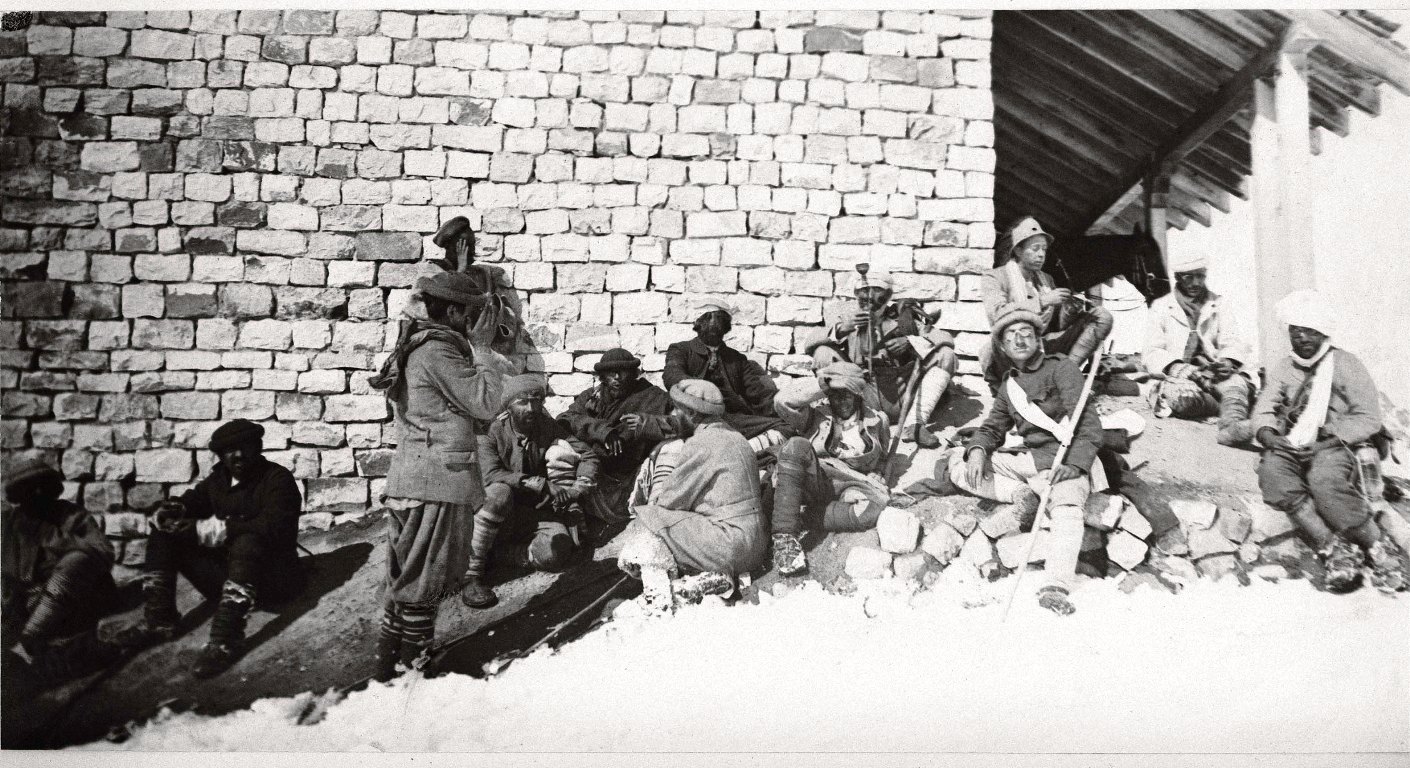

On the way back to Burzil, I ran into the last of my 25 coolies who were to undertake with me this major crossing of the pass in the snow on the following day. The distance is 18 miles, around 30 kilometres, and, with 40 pounds packs on their bags, quite a tidy piece of work for the coolies. The night remains clear and cold with beautiful moonshine early on. I am awoken at 3, and have packed and had breakfast by 4. But it is half 4 before we get underway, a long convoy lit by lanterns, comprising around 40 people, including two women.

An official of the Governor of Chilas had been at the bungalow for several days, waiting the right time to get across the pass. On the journey to his new posting on the north-west border, he had taken with him his wife and mother. These poor women had a heavy day ahead of them. It was quite odd to see the young woman, in particular, walking around up there in the ice and snow in her brilliant red tapered trousers and scarves of many colours, mostly bright green. The older woman was carried for the last stretch and, just before the top of the pass, I gave her a good dose of cognac, the younger one declined.

We carried on slowly in the lantern light for two hours then the path became partially invisible in the snow drifts and an icy wind drove hard against us. But then it got better towards 9, the sun came out a little and three mail-runners went ahead to show us the way. At 10 we had a short rest at a wooden house mounted on a high platform, really intended for the mail men in the winter, and at about 12 we arrived at the rest house at the top of the pass.

To our utter astonishment, we found quite a large party up here, made up of both ponies and people. There were two rajas from the border, understood to be on the way to the coronation in Delhi. Some members of their retinue looked pretty savage. The elder raja had a huge brown horse with him and, when he heard I was German, he proudly showed me his huge Mauser. I joined them in savouring their baked delicacies including apricot pastries and soon had to set off again. But I also saw how the Raja sent 30-40 unladen ponies ahead in order to beat a pathway through. I felt sorry for the poor animals as they fell repeatedly into the deep snow. Now we were pushing on downward and had, as already suspected, far less snow on this side and we had a much better path because so many people and horses had come up already, so we covered the eleven miles to Chillum Bungalow in a comfortable five hours. But I was still pleased to get to the end because 13 hours in transit was enough for everyone.