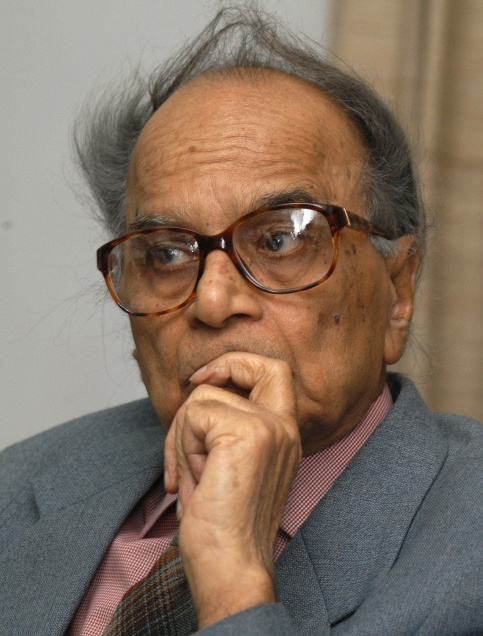

Son of a partition migrant from Peshawar, Ved Marwah, IPS (September 15, 1934 – June 5, 2020) headed Delhi Police and the NSG before being appointed as an adviser to Governor Jagmohan in 1990. He was also marginally involved in securing the release of Rubaiya Sayeed, who was kidnapped by JKLF in 1989. A week after his death in Goa, read some of his first-hand memories during his three-year stint in Srinagar before being elevated to a governor

DGP Saxena’s briefing had not prepared the Governor about the grave situation that was developing in Srinagar. The whole night both the Governor and I were kept awake by distress calls from Srinagar. The situation in Srinagar had worsened and the mobs had virtually taken over the city. The Kashmiri Pandits were panic-stricken. They feared their massacre by the uncontrolled violent mobs which were on the rampage in Srinagar.

Apparently, taking a leaf out of the Romanian demonstrations, which were being highlighted by the media, including Doordarshan, those days, it appeared as if the whole population of Srinagar had come on the streets shouting slogans such as Allah-o-Akbar, Azadi and Death to Indian dogs. The high-powered loudspeakers in all the mosques were screaming these slogans, apparently from recorded cassettes. The Pandits were scared and were making desperate calls to Jammu and New Delhi.

The administration in Srinagar had been under tremendous pressure for some time; it panicked and literally disintegrated. Instead of taking action to control the situation, the senior officers who were left in Srinagar just disappeared from the scene.

We left for Srinagar by the morning flight on 21 January 1990. The distress calls and many alarming reports had prepared us for the unruly scenes, but we were unprepared for what we actually saw on the ground. Some of the senior police and administrative officers played the vanishing trick. The police, and even the CRPF, had disappeared from the city streets. The militants had literally taken over the city and were demanding the immediate release of over a hundred suspects, whom CRPF had rounded up after the large-scale searches at Chota Bazar and Guru Bazar on the previous day.

There was complete confusion about why these large-scale searches had been ordered by the DGP before his departure for Jammu, and why no proper arrangements had been made for their quick screening and for dealing with a possible backlash. Searches in the downtown areas are a difficult proposition even during normal times. The DGP, apparently, did not anticipate the reaction and had not made plans to deal with all possible contingencies. What was worse, the inexperienced DGP had not taken the local police and the state administration into confidence before ordering the CRPF to conduct these searches.

In his apparent anxiety to impress the new Governor, he was keen to demonstrate his readiness to take effective action against the anti-national forces. A large number of young men were rounded up by the CRPF for screening. The task of screening was unnecessarily delayed. The arrests caused widespread anger, which the militants fully exploited. They could not have hoped for a better opportunity. The Inspector-General of the CRPF, Joginder Singh, was a harassed man though he was trying his best. Unwittingly a very difficult situation had been allowed to develop by an inexperienced police leadership.

We reached Raj Bhawan under heavy armed escort. Very little was functioning in the Raj Bhawan – there were no power and heating arrangements. It was bitterly cold and we sat in the Governor’s office in our overcoats. The Governor sent for the Corps Commander, Lt General MA Zaki, to discuss the situation in the city and he arrived within a few minutes to give his assessment. It was apparent that there was no alternative but to hand over the situation to the army.

Gen Zaki was asked by the Governor to take whatever steps he considered necessary to bring the situation under control. To disperse the unruly mobs which were now attacking and burning government property, the army had to open fire at Gowa Kadal, LaL Bazar, Safa Kadal and Hawal. A number of persons were killed in the army firing. The army figure was twelve killed, but others put the figure at around thirty.

As it usually happens after such an action, the killings and the firings further inflamed public passions. Rumours spread like wildfire that hundreds of people had been killed in the army action. The situation had been brought under control by the evening, but at a very heavy cost. These tragic incidents put Governor Jagmohan in a tight spot. The searches and arrests, the violent demonstrations and the army firing that followed—all coincided with the new Governor taking office and the people put the entire blame on him. There could not have been a more inauspicious start to his second tenure as the Governor of J & K. He made matters worse for himself by taking no disciplinary action against the police officers guilty of grave professional lapses.

The Governor succumbed to the usual plea that taking action against the police would demoralize the force. The force does not get demoralized if justified disciplinary action is taken against guilty officers but it does get demoralized if the guilty get away scot-free. Allowance can be made for bonafide errors of judgment, but blatant illegal acts, or gross mismanagement by officers should not be ignored and pushed under the carpet.

Incidentally, all the arrested persons were later released, except six, under the orders of the Governor. Even these six were released after a few days. What a colossal mess, and for what? It had grave consequences for the situation in Kashmir. It gave a tremendous boost to militancy in the Valley, almost as much as Rubaiya Sayeed’s kidnapping a month before.

The Police Strike

On 22 January 1990, to win over the loyalty of the J & K police, the militants put through a diabolical plan of action to incite them to revolt against the government. A palpably false rumour was spread that the CRPF had killed four members of the J & K police in a shooting incident not too far away from the Police Lines, and that the dead bodies had been brought to the Lines. The policemen who were already sour over the searches— which were undertaken without taking them into confidence—and the subsequent incidents, got very angry on hearing this “news”.

They struck work and some of them took out a procession shouting the same slogans: Hum Kya Chahte Hein—Azadi (What do we want -freedom) and Indian dogs get out. They were in uniforms and carrying their official weapons with them. Marching through the city roads, the procession reached the Police Lines around noon, where the City Control Room is also situated. The situation there took a menacing turn when the armed processionists started misbehaving.

The Governor asked me to immediately rush to the Control Room and deal with the situation. On reaching there I found DGP Saxena and other senior officers already present. The DGP bluntly told me that there was no alternative to using force against these policemen, who had violated all norms of discipline. The small army contingent, which was stationed in the Control Room had already taken up positions and the situation was explosive. The DGP, of course, had every reason to feel angry. There cannot be a bigger humiliation for a leader than to see his own men behave in this fashion. It was, however, clear to me that an armed clash between the army, the paramilitary forces, and the striking J & K policemen would have very serious repercussions. Since both had automatic and semiautomatic weapons, the number of casualties could be heavy in case of an armed confrontation.

Taking a calculated risk, I asked the DGP to hold on for some more time. I had to assure him that in case things went wrong the responsibility would be entirely mine. The DGP agreed and the imminent clash was averted. I invited a deputation of the striking policemen to come and talk to me about their demands. The Commandant of the J & K Armed Police, Tikoo and the DGP displayed tremendous courage in going down and talking to the agitating policemen. This angry mob could have done anything. Inspector General Nomani seeing his DGP going down also joined him. I must confess that I was quite alarmed at DGP’s move. But then during such crisis situations there are moments when such irrational acts change the entire complexion of the situation, as it happened at that time.

The presence of the senior officers in their midst appeared to have had a sobering effect on the agitating policemen. The DGP addressed them from an improvised platform. He was able to persuade them to send a deputation to talk to me in the Police Control Room. The deputation gave me their version of what they had heard and demanded withdrawal of the CRPF from Srinagar and the arrest of the CRPF officers who were supposed to have shot dead their compatriots.

I gave them a patient hearing, but I detected some false notes whenever they talked about the killing of their colleagues. They wanted to concentrate more on their demands for the withdrawal of the CRPF than on the incident which had triggered off this agitation. I asked them, “Where are the dead bodies?” They looked at each other and then said that they were lying nearby in one of the barracks of the Police Lines and they were going to be buried very soon. I asked them for the details about their names, etc, so that their families could be given ex-gratia payment immediately.

They were unwilling and unable to provide these details. I also assured them that the orders had been given for the registration of a murder case and that the case would be investigated by the J & K Police officers. The members of the delegation, who were till then shouting angrily, became quiet. This made me suspicious. I asked the deputation to accompany me to the barracks, where the dead bodies were supposed to be lying so that I could pay my homage to them. To cut a long story short, it was found that no such incident had taken place at all and no J & K policemen had been killed in the shooting by the CRPF. This canard had been spread to incite the already sullen J & K policemen to rebel against the government. It took a little time to inform all the police stations in the Valley where the strike had already spread. Complete normalcy could be restored only after a couple of days.

One shudders to think of the consequences if a shootout had taken place between the paramilitary forces and the agitating armed policemen. It was obvious that a very deep conspiracy was unfolding itself in the Valley, and that many in the administration including some J & K police officers were involved in it.

I returned to Raj Bhawan late in the evening to inform the Governor about what had happened. The DGP was told to send reports against the police officers who had incited their colleagues to agitate and had taken a leading role in spreading the canard. One hundred and one officers were removed from service. At the same time, the other legitimate demands of the policemen which had been pending for some time were accepted, and immediate action initiated to fulfil them. A two-pronged strategy to cleanse the J & K police from anti-national elements, and to raise their morale by meeting their legitimate demands was put into operation.

JM Qureshi, the other Adviser to the Governor, reached Srinagar via Jammu a couple of days after the police strike. His arrival created an embarrassing situation, as we were both handling security operations, because the Governor had not allocated the portfolios between the two of us. I politely, but Qureshi in his inimitable style a little more bluntly, requested the Governor to allocate our portfolios, so that we could start functioning in a more systematic manner. One could understand the pressure of the situation and the enormous problems the Governor was facing for the first week or so, but this could not go on for long. For reasons best known to him, he postponed the allocation of work for quite a few days. This created a certain amount of avoidable confusion. Qureshi had worked as Adviser with Jagmohan earlier and Jagmohan decided to allocate the same portfolios to Qureshi which he had handled in 1986 which included the portfolio of Home and Police. My portfolios were Finance, General Administration, Tourism, etc.

Having failed in their diabolical plan to gain independence, the conspirators and their Pakistani sponsors decided to increase the level of terrorism in the state. On 24 January 1990, four IAF officers were shot dead by the terrorists while they were waiting in the morning for the IAF bus to take them to their office. The killings were done very much in the Punjab terrorist style. The assailants came on motorcycles and shot dead the unarmed IAF officers. The crime was committed, apparently, to impress the people that they were in complete command and they could even take on the armed forces.

There were rumours that something sinister would happen on 26 January, Republic Day. Very elaborate security arrangements had been made to ensure that nothing untoward took place. The Governor did not go to Jammu to take the salute at the main Republic Day parade as per past practice. The day, however, passed off without any incident, though there were not many people, not even many state government officials, to witness the parade. The militants imposed “civil curfew” and the streets of Srinagar did not see much traffic that day. The city had still not recovered from the incident of the last few days and the Indian Republic Day was hardly a joyous occasion for most of its citizens.

In the next few days the situation showed signs of improvement, though it was nowhere near normal. There was no let-up in the number of terrorist incidents and the militants continued to target the Kashmiri Pandits. On 2 February, Satish Tikoo, a Kashmiri Pandit, was shot dead in front of his house in Habba Kadal. I accompanied the Governor to Tikoo’s house to offer our condolences to the bereaved family. The family members were agitated and insecure and expressed a wish to migrate to Jammu. It was obvious that the militants had succeeded in scaring the Kashmiri Pandits, but their large-scale migration started later, in the month of March.

On 8 February, two off-duty BSF constables were shot dead near the BSF headquarter at Srinagar. On 12 February, Bhan, an official of the Intelligence Bureau in Srinagar, was shot dead in a crowded bazaar. The IB, which over the years had developed an effective intelligence network, suffered one shock after another. They were under tremendous pressure and the militants were doing everything to reduce their effectiveness.

Killing of Lassa Kaul

The government media was also targeted, so that it may not dare to publicize its own version. The Station Director of Srinagar Doordarshan was in an unenviable situation. On the one hand, he was being threatened by the militants to telecast only their version, while on the other, he was being pressured by the administration not to succumb to terrorists’ threats. Lassa Kaul, the Station Director, was a popular figure in Srinagar, but he was finding it difficult to resist the militants’ threats. They were openly threatening him to toe their line or else.

On 13 February 1990, he paid the price for resisting the terrorists and was shot dead. He had gone to see his old father in his house at Bemina where he was shot dead. With his killing, the militants achieved another major objective. The AIR and Doordarshan staff struck work. The TV and AIR stations had to be shifted to Jammu, as the staff refused to function from Srinagar. The exhortations of the visiting I & B Minister and the Director General, who had also come to Srinagar, were of no avail in persuading them to keep the stations functioning from Srinagar. The AIR and Doordarshan lost much of their credibility in the Valley, as a consequence of this shift.

Dissolution of Assembly

The situation on the political front was also getting complicated. Governor Jagmohan was not fond of Farooq Abdullah, and made no secret of the fact. He criticized him publicly. Farooq Abdullah had no love for Jagmohan either. Jagmohan suspected that after getting the dirty work done by him, the Centre would dump him and bring Farooq Adbullah back as Chief Minister. In a surprise move, the Governor dissolved the State Assembly on 19 February 1990, exactly a month after assuming power. It took most of us in Srinagar completely by surprise. The Union Home Minister, who had gone on, tour to Bombay rang me up to find out how a political decision like that could be taken by the Governor without even informing the Home Ministry. I told him that we knew nothing about this decision and were taken as much by surprise as he was. By dissolving the Assembly, the Governor pre-empted any Central move to revive it.

The Governor was, however, not prepared for the sharp criticism that followed the dissolution by almost all political parties except BJP. The Prime Minister was angry and was reported to have used some very strong words to describe the Governor’s action. The dissolution of the Assembly had not been a wise move. The political leaders of the state who had already lost their credibility with the people were now made totally irrelevant. The dissolution could be justified only if the ground had been prepared for holding fresh elections in the near future. As there was no possibility of holding fresh elections in the foreseeable future, the dissolution was not justified.

Under the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution, the governor is empowered to dissolve the Assembly, but only for a maximum period of six months. Further extension can only be through President’s rule. The dissolution completely blocked the political process and achieved little except creating serious difficulties for the Governor. The situation which was showing some signs of returning to normalcy started deteriorating very fast. Aware of the strong adverse reaction in New Delhi, rumours about the imminent removal of the Governor started floating in a big way. The setting up of an All-Party Advisory Committee on Kashmir was interpreted by many as the Central government’s first move to clip the Governor’s wings. The leaders of CPI, CPI (M), and even some Janata Dal leaders like George Fernandes were openly critical of the Governor.

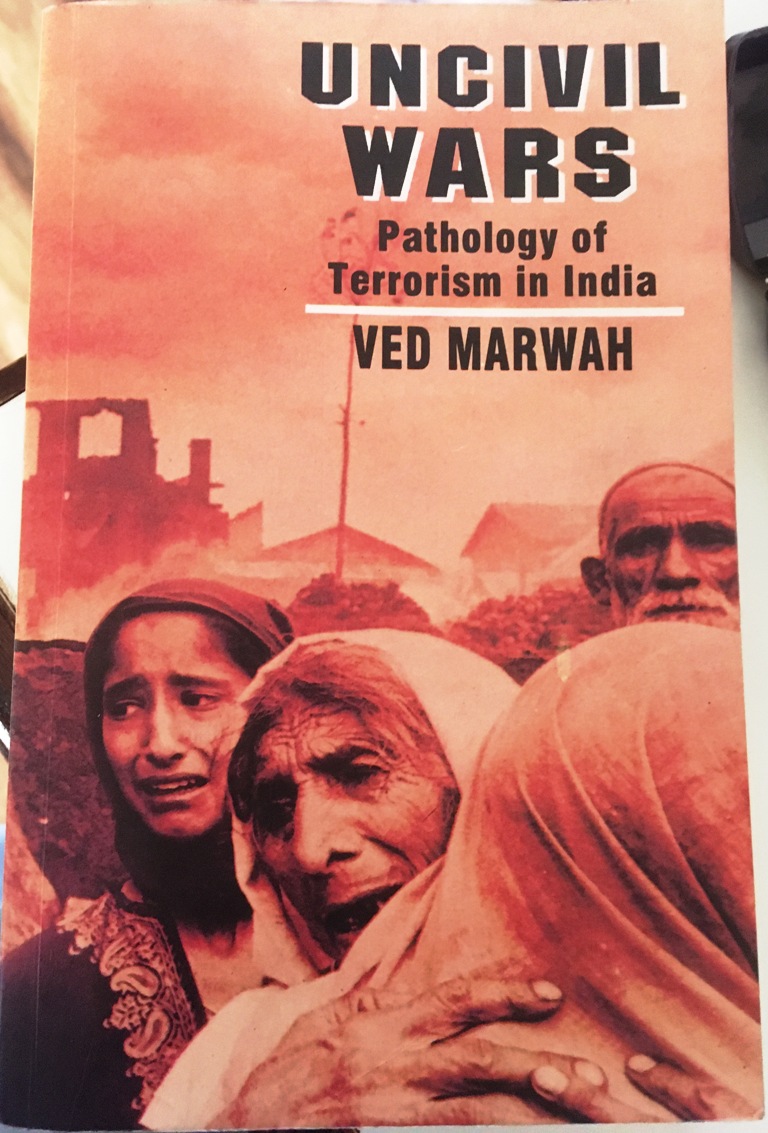

(These passages were excerpted from Marwah’s book Uncivil Wars: Pathology of Terrorism In India that HarperCollins Published in 1995)