The cultural industries of Kashmir can become the harbinger of an enterprising future for commerce, says Haseeb A Drabu.

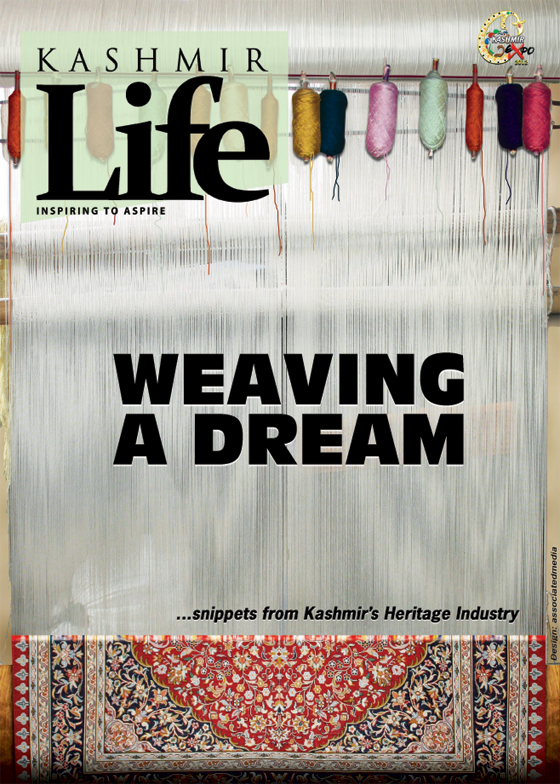

Handicraft is not any odd enterprise or ordinary business for us in Kashmir. It is the regenerative symbol of our priceless cultural heritage, the zenith of the creativity of our craftsmen, and the expression of our collective emotions.

So interwoven are our crafts with our culture that the craft enterprises should be referred to and dealt with as the “cultural industry” of Kashmir and not as a traditional industry. Indeed, cultural industries are recognised by the UNESCO and not only do they get protected by intellectual property rights, GATT even accords them exceptional tariff treatment.

Cultural ramifications apart, the handicrafts segment has been, and is, the most crucial segment of the Kashmir economy. The fact is that handicrafts are next only to horticulture in its significance for the Kashmir economy.

From early 16th century, crafts be it carpets, shawls, papier-mâché, crewel embroidery, wood-carving or any other form of craft, have been a source of livelihood for the artisans, an extremely profitable business for the traders and exporters and passionate indulgence for the elite consumers.

Like much else in Kashmir, the handicrafts sector has degenerated over time. In the late 18th century and early 19th century, the Kashmiri shawl, for instance, had reached its widest and unbelievable level of popularity and influence in the West.

During this period the Kashmir shawl became the most well-known and important article of female dress and fashion. It is well documented that Napoleon’s wife, the Empress Josephine possessed a large collection of Kashmir shawls, rumored to be around 200.

It was not a one way trade. The Kashmir shawl which was originally made as an article of male dress, under the influence of western fashion tastes and market suaveness, became a woman’s accessory. This contributed to its stature and survival.

During the 19th century the highest quality Kashmir shawls were sold in the best fashion houses in Paris, London and New York for extraordinary sums (see box item).

Now, the craft has deteriorated: the best pieces produced in Kanihama today have warp counts – the number of foundation threads per inch – of only 50 to 60 while the shawls made earlier averaged over 200 per inch. The craft enterprises are in disarray: Amritsari replications are ruling the market. The craftsmen are in distress: a brick kiln worker, or an auto rickshaw driver or a peon in government service earns more than an artisan.

Kashmir is “rich” in crafts, but Kashmiri craftsmen are living in poverty, if not penury. How can this business do well, if the producers are not earning enough? In fact, they have been marginalised and work as wage labourers. There can be no bigger indictment and perversity of the economic policy pursued over the years.

Government interventions in the crafts economy of Kashmir must be based on an understanding of two aspects; First, at the macro structural level, it needs to be appreciated that the handicraft enterprises are the most ideal for an economy like ours: low capital use, high employment intensity and a wide geographical dispersal. It is a business that can generate huge employment in J&K with minimal use of capital. Rather than treat it as a small scale or household industry, it ought to be treated as a “craft economy”.

Second at the micro differentiating level– the uniqueness of our crafts. The most unique feature the Kashmiri handicrafts, be it carpets or shawls, is that they blend matchless artistic excellence with a great deal of practical functionality. They are not mere pieces of decorative handicrafts like other kinds of handicrafts produced all over the globe. The manner in which our handicrafts blend aesthetics in design with the functionality in form is truly unique.

While the first one provides the economic logic for building this sector, the second one provides the business logic for its growth. The two together can provide an engine of economic growth and financial prosperity.

The focus of all efforts – governmental and private – has to be craftsmen who are at the core of this sector. The day craftsmen get their due, the problems plaguing the handicrafts enterprises would be over.

In our system today, the craftsman is an “artisan”, an Italian term for a “skilled manual worker”. We need to value him an “artist”. The difference is more than mere semantic; it has wide ranging implication: from social status to pricing to patenting.

Artisans create objects with a sense of utility; they make goods for a functional purpose. Their work can have beauty or artistic merit. Artists, on the other hand, create from the point of view of imposing their vision on to the materials. They make things that need not have a utilitarian value. It is all about creativity. Our craftsmen produce products that have both!

As such, the heart of any transformation exercise should be the question; how does one convert the “artisan” into an “artist”. He has the skills and the medium; the creativity and the creation. What does he lack?

The approach has to be to treat this sector as a sub-set of the knowledge economy. It is perhaps the only production activity in which the knowledge and skills are used to create a tangible physical asset at the origin.

There is a lesson to be learnt from the success of software industry. The software companies provided the software developers and their employees ESOPs and virtually made them entrepreneurs. We need to do the same.

Instead, the opposite has been happening in handicrafts – entrepreneurs have been marginalised to become wage labourers.

Far from benefiting the artisan, the person who creates these masterpieces is the one who gets the least when the going is good and suffers the most during the hard times.

This then leads us to another aspect. Despite this and its fame – over time and across space – a pashmina shawl, for instance, is still simply a “commodity”. It has to be seen a “product”. Indeed, ideally a work of art. What is required is to make it a branded product; a unique non-replicable product that is based on a process patent or a design patent.

The move of our handicrafts from being a “commodity” to being a “product” requires branding. It is ironic that in spite of the fact that “Kashmir” is the most recognisable geographic brand, Kashmiri handicrafts are not branded.

If we see the crafts, for example lace from a small country like Belgium, it is so well branded that not only has the status of an artifact but is priced phenomenally well which makes it a lucrative activity for the artisans. Exactly the opposite is true in Kashmir. The crafts made by the artisans in Kashmir lack a product brand image.

Contrary to building a brand, there seems to have a brand erosion over time. In the early 19th century, a pashmina shawl has such a brand image that Napoleon gifts it to his wife, but now we are struggling to compete with the Amritsari imitations.

There is also very little attention to detail. Even a Rs 1 lakh pashmina shawl comes in a transparent polythene bag! Compare this with the manner and sophistication of packaging of a Hermes ties costing just Rs 10,000.

The transition of all our handicrafts from generic commodities to highly differentiated products and by implication from being lowly priced to being high priced is difficult one that needs intervention at three levels, viz; finance, technology and marketing.

Operationally the biggest structural problem with handicraft trade, especially carpets and shawls, is the merger of finance facility and sales functions. The intermediaries who buy the handicrafts are the one who also finance its production. The two have to be separated. This will give the artisan a better price discovery mechanism as also greater flexibility in selling. Otherwise he is like a bonded labourer as he is forced to sell to those who finance his production as well as livelihood.

There hasn’t been any technological intervention in the sector for decades now. The production process is unchanged. There are two types of technological interventions that need to be made: soft technology like design and branding and hard technology like physical infrastructure which will improve efficiency. The artisans are still replicating and copying old designs while in other countries especially Iran is thriving on the latest designs and use of software technology. All these aspects are ideally suited and amenable to use of software technology. There is need to upgrade the present infrastructure and induce scientific interventions into the sector to make it more viable.

What the artisans, craftsmen and all those associated with this trade need are not subsidies and “industry status”, but a craft policy which focuses on all these aspects.

It is imperative that we align our skill building with the requirements of our crafts sector. For instance, it is high time that the University of Kashmir offers an MBA in Crafts Management. This will create a talent pool that will professionalise this trade and market around the world along modern lines.

It important for us not only to preserve this art, but also to propagate this as a business and professionalise the organisation of its production. As such, to build a sustainable business for handicrafts, we have follow a 3 P approach: preserve, propagate and professionalize.