Powerful Modi government is reportedly toying with the idea of a fresh delimitation for Kashmir assembly by undoing a legislative freeze. While there is no official word, the debate is gradually strengthening the disempowering debate. But the evolution of the institution of assembly suggests the delimitation process is time-consuming and is unlikely to change Jammu and Kashmir’s political demographics, reports Masood Hussain

Kashmir played the key role in getting the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) an exceptional landslide mandate to rule India. Firmly in the saddle, it is yet to come out of its Kashmir juggernaut. For decades of its birth and subsequent evolution to the Indian centre stage, the BJP always had its Kashmir prescription. Now are the testing times.

The party is caught between two loose ends of its priorities –wresting power in Jammu and Kashmir from the home-grown political class and effecting interventions to undo the distinct constitutional status of the state. For achieving both the targets, managing the state assembly is important. The party, however, is yet to finalise whether it wants a Hindu Chief Minister or a BJP Chief Minister for Jammu and Kashmir. The party would require a sort of a supportive assembly for any kind of intervention it wants.

Apparently, the state assembly is the priority. With Amit Shah, the literal Padshah, as the Home Minister, the priorities are expected to be much clearer by the end of June. Indications suggest, there could be some kind of clarity on certain constitutional issue by or before the end of June. Shah is flying to Srinagar and he is expected to talk with more clarity on issues.

On the Kashmir assembly management front, a fierce debate has been unleashed suggesting the BJP would opt for delimitation and increase the numbers of the state assembly. This, the debate insists, will mark an end to the discrimination that Ladakh and Jammu were historically subjected to by the Kashmiri political class. This, the argument goes, will also help change the ten assembly seats reserved for Scheduled Castes which have remained unaltered for the last three assembly elections.

The larger issue that is being vociferously talked about – the most interesting case has been Jammu and Kashmir’s former state police chief, Dr S P Vaid–is that of West Pakistan refugees (residents of Pakistan but not state subjects) and the Displaced Persons (Residents of PaK but state subjects). The idea being toyed around is that some of the 24 berths reserved for PaK territories would be de-frozen and given to the DPs.

As Kashmir was busy celebrating Eid amid heavy rains and interrupting gun battles, the media, social media and the political class remained busy with this issue last week. “Who knows if this debate is for real or just optics,” one senior politician, also a former minister said. “But the reality is that this is an issue regardless of everything.”

Current Status

Jammu and Kashmir’s legislative assembly has a total of 111 berths of which 24 have remained perpetually reserved and unfilled for the territory of Jammu and Kashmir in Pakistan’s control –Muzaffarabad, Mirpur, Gilgit and Baltistan. The remaining 87 seats are elected directly of which 37 are for Jammu; 46 for Kashmir and four for the arid Ladakh desert. The governor, as head of the state, does nominate two women to the assembly to add to the representation of women. They lack voting powers.

Ideally, the berths in the state assembly are to be altered after every headcount, according to the Jammu and Kashmir Representation of the People Act, 1957. The assembly, however, legislated on the issue in 2002 and froze any alteration in the status quo till 2026. “..until the relevant figures for the first census taken after the year 2026 have been published, it shall not be necessary to constitute a Commission to determine the delimitation of Assembly Constituencies in the State under this subsection,” reads the amendment. The assembly also amended Section 47(3) of the state constitution.

Later, when Bhim Singh of Panthers Party went to the Supreme Court to challenge the amendment, the case was dismissed on November 10, 2010. This essentially means the Supreme Court upheld the legislative intervention of the assembly.

The amendment restricts any change in the numbers till the 2031 census is out. It essentially means the nearest possibility of any change in numbers cannot be before 2035.

This is where Jammu feels discriminated against.

“The delimitation exercise that is believed to be under consideration is the first major step that the government is considering so as to ensure equitable representation in the state assembly from all regions of the state,” Saroj Chandha, a former army officer wrote in Times of India. “Currently, it is heavily skewed in favour of the Kashmir region at the cost of the Jammu and Ladakh regions. Kashmir accounts for 15.8% of the area and 54.9% of the population. Jammu region accounts for 25.9% of the area and 42.9% of the population while the Ladakh region has 2.2% of the population but 58.3% of the area.”

Since the delimitation exercise takes care of the terrain, geography and other indicators of progress and development, in addition to the fundamental demography, the voices in Jammu believe they will get lot many seats enabling it to ruler Jammu and Kashmir. Ghulam Nabi Azad remains the only Jammu Chief Minister but he is a Kashmiri speaking Muslim as well. A section in Jammu, these days, talks in different lingo: “We have as much land as Israel has”.

Though the MHA or the Raj Bhawan in Srinagar has not said a word on this debate, the support for the assumed process has hugely grown in Jammu.

“We are hopeful that Delimitation Commission will be constituted and it will give one-third of the seats reserved for the PoK to the Displaced Persons settled here,” Choudhary Lal Singh, who now heads the DograSwabhimanSangathan (DSS)said. “Two seats in Kashmir should be reserved for Kashmiri Pandits.”

The DP leader Rajiv Chuni also hoped that at least eight of the berths reserved for PoK are de-frozen and given to his community.“PoK DPs have voting rights but because of their scattered population, the community has no representation in the State Assembly and hence voice of the community remains unheard at the highest forum in democracy,” Chuni was quoted saying. “Delimitation process must be completed in Governor’s rule as no Kashmir-centric party will digest granting power to Jammu, Ladakh and PoK and the same should be coupled with opening one-third PoJK seats for Displaced Persons settled here.”

BJP leaders in the state have “hailed the decision” even when there is no line on record from anywhere. “Jammu has been discriminated (against) right from 1947 at the hands of Kashmir-centric governments till today,” Jammu Province People Forum (JPPF) leader Pavittar Singh Bhardwaj said. “Once the due political empowerment is vested in Jammu as per norms, the state may have a Chief Minister hailing from Jammu to fulfil the long-pending aspirations of Jammuites.”

Some Gujjar leaders have also joined the debate insisting that some of the constituencies must be reserved for Scheduled Tribes (ST) on the pattern of SCs

But how will the delimitation help Jammu to get empowered? Is it possible to tailor-made an increase in the number of assembly berths? It is important to understand the evolution of the institution of assembly first. The assembly predates the partition.

Praja Sabha

The BJ Glancy Commission that Maharaja appointed in wake of the 1931 massacre (remember July 13), submitted a long report in May 1932. On its recommendation, a Franchise Committee was constituted under Sir Barjor Dalal, the then Chief Justice of the state high court, with LA Jardine, a government of India officer, Thakur Kartar Singh and Sheikh Abdul Qayum as members. In March 1933, Sir Ivo Elliot was appointed Franchise officer. The then Prime Minister EDJ Colvin ordered the release of Sheikh Abdullah on May 5, 1932, to ensure the Committee work properly.

On December 30, 1933, the Committee recommended a 75-seat assembly on the Morley-Minto Model including 33 elected and 30 nominated members. Balance 12 seats – six non-official experts and ministers, were officials to be appointed to the assembly by the Maharaja.

“The delimitation of the constituencies was recommended to be done on the territorial and communal basis,” Annu Balla writes in her doctoral thesis Relations Between The Union of India and The State of Jammu and Kashmir From 1947 to 1975. “The entire state was to be divided into 12 rural and 2 urban districts. Urban districts included Jammu city and Srinagar city, whereas 12 rural districts were the wazarats of Jammu, Udhampur, Reasi, Kathua, Mirpur, North Kashmir, South Kashmir, Muzaffarabad, Ladakh and Gilgit and two Jagirillaqas of Poonch and Chenani.”

The members were to be elected on a communal basis. Every constituency would elect a Hindu and a Muslim member: In Mirpur, Northern Kashmir, Southern Kashmir and Poonch both members were to be elected by the Muslim electorates; Sikhs got separate representation; In Jammu city one Muslim member was to be elected by the Muslim electorate and two Hindu members were to be elected by Hindu electorate. Similarly, Srinagar city would be represented by five Muslim members and two Hindus.

The recommendations were rejected by the Muslim leadership. Choudhary Ghulam Abbas was arrested. When the Maharaja promulgated the law for setting up Praja Sabha, of the 33 elected 21 were to be Muslims, 10 Hindus and two were to be Sikhs. The law kept Maharaja’s Privy Purse, organisation and control of the state Army and the provisions of the Constitution Act with himself, according to Balla. In the first election in 1934, Muslim Conference won 19 of 21 seats allocated to the Muslims. On February 11, 1939, elected berths were increased to 40. But the changes did not impact politics. By 1941, NC members resigned against ‘arbitrary powers’ to the Prime Minister; introduction of the Devnagri scripts in schools and concessions to the Rajputs and Hindus under the Arms Act.

The situation changed quite fast as India’s freedom movement and that of Kashmir left quite a little for Maharaja. By December 1946 when the Constituent Assembly of India was set up, Maharaja – on the request of the Muslim Conference and the Hindu Sabha, avoided joining it. Then partition took place and Kashmir got involved and sliced in two parts.

Constituent Assembly

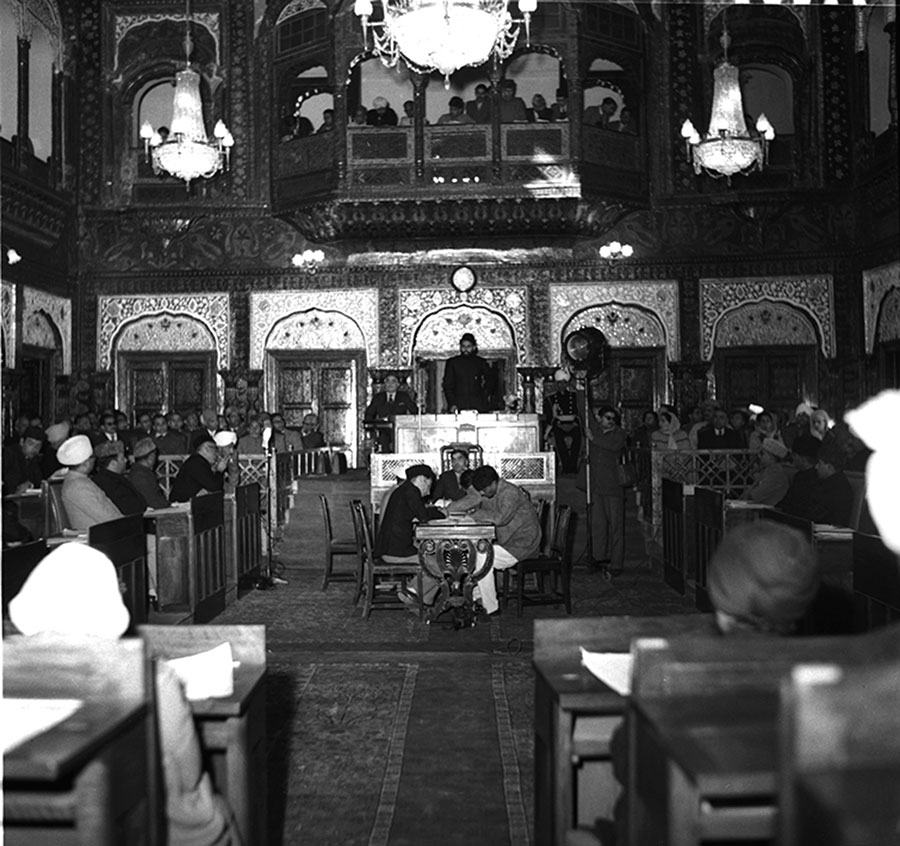

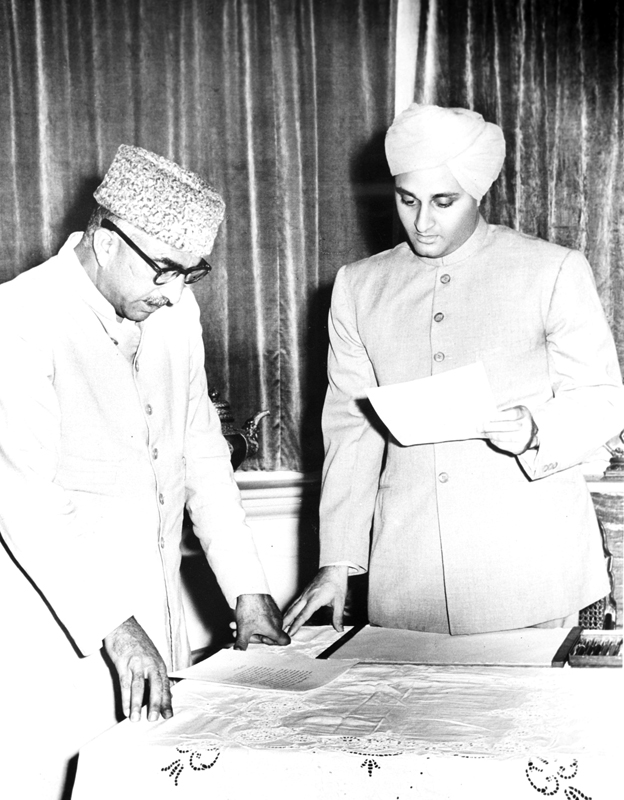

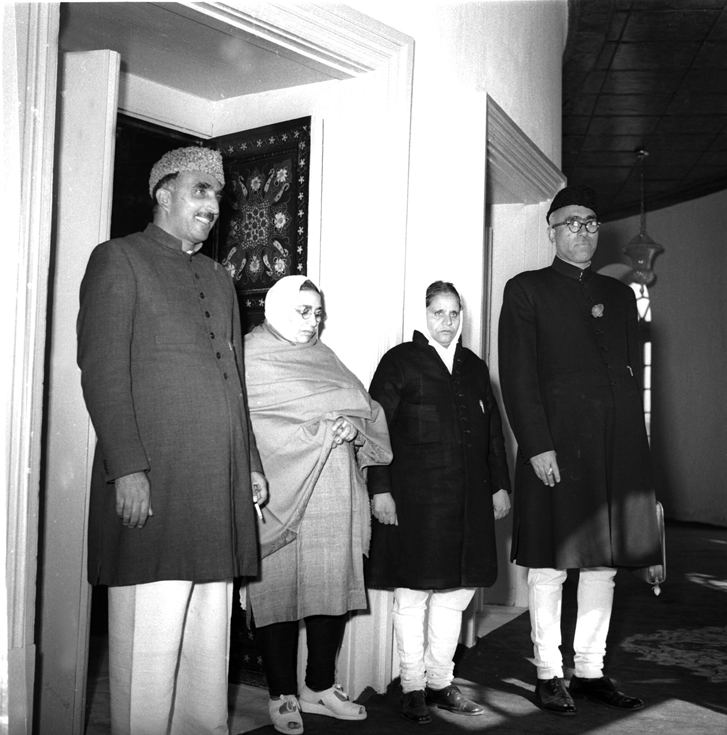

Sheikh Abdullah, who had taken over as the Emergency Administrator of the state in later 1947, was appointed the Prime Minister on March 5, 1948. By May 1, 1951, an order was issued to constitute the Constituent Assembly for the future Constitution of the state. On July 11, 1951, the Jammu and Kashmir government set up a 5-member delimitation committee headed by Justice Muzaffar A Shahmiri that suggested a 100 seat house. Of these 25 seats were earmarked for 37 per cent of the population living in 40 per cent territory of state under Pakistan control. Jammu got 32 seats and 43 were given to Kashmir including Ladakh. The 100 constituencies were delimited on the basis of a member for every 40,000 residents. NC won all the 75 seats, 73 of them unopposed.

The House had Constituent and legislative powers. By 1956 the drafting of the Constitution was completed and by January 26, 1957, the Constitution was in vogue. The only difference was that Sheikh who had made the inaugural speech in the assembly was sulking in jail.

Next Delimitation

In the run-up to the general elections of 1967, Delhi decided to do away with permitting nominated members from Jammu and Kashmir to sit in Lok Sabha and wanted a direct election. A Delimitation Commission was set up. Led by G L Kapoor, it had R C Soni, a retired judge of Punjab High Court and K V Sundrum, chief election commissioner, as two other members and P S Subramanian as its secretary. This Commission gave Kashmir 42 berths, Jammu 31 and Ladakh 2 seats in the 75-member house. Kashmir got three, Jammu two and Ladakh one LokSabha seat, a position that is still unchanged.

Post-1975, there was an interesting development when the National Conference government led by Sheikh Abdullah announced an assembly seat to Mendhar. “Mendhar was part of the Surankote constituency and delimitation was carried out and then this seat was created,” Shah Mohammad Tantray, the former representative of Poonch Haveli said. “Some area from our constituency was added to it and it became a full-fledged constituency.”

But what was interesting was that the additional berth was created within the overall sealing of 100-members. “There was a constitutional amendment,” former Finance Minister Abdul Rahim Rather said. “The amendment reduced the number of seats from PoK quota to 24 and the resultant one was given to Mendhar.”

That is perhaps why the supporters of PaK quota de-freeze are seeking a similar route for giving representation to the displaced persons (DP) living in Jammu. They are voters to assembly but they claim they are scatted across the state and lack voice. It was on basis of their arguments that a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) recommended that one-third of the 24 berths (eight seats) in state assembly kept symbolically for PaK, be de-freezed for Displaced Persons (residents of PaK) and West Pakistan Refugees. For this, the JPC recommended an amendment to the constitution.

The PaK assembly has 49 members of whom 12 are reserved for the refugees settled in Pakistan.

The Major Delimitation

Normally, after every census, there has to be delimitation. Under routine circumstances, a delimitation commission was constituted after the 1981 headcount under the leadership of Justice J N Wazirwith Justice Jalaluddin as a member and India’s Chief Election Commissioner as an ex-officio member. After Wazir’s demise, Jalaluddinsucceeded him with Justice K K Gupta as a member. On the basis of a letter, the government initiated a constitutional amendment to add 11 seats to the House –four to Kashmir, five to Jammu and two to Ladakh. The Commission faced a peculiar situation after Jalaluddin’s resignation that paved the way for Gupta’s elevation as Chairman as Justice A M Mir was inducted as a member. The crisis continued and the Kashmir situation led to the fall of the Dr Farooq Abdullah government in 1990.

The Commission was revived later but CEC T N Seshan refused to sit in a Commission where the Chairman enjoys lower status. The rules were amended and his membership was given to his Deputy. Later Justice Bilal Nazki was inducted into the Commission and the revived and refurbished Commission published its report on April 27, 1995. Under the new system, the Kashmir House has 111 members – 24 reserved for PaK; four seats for Ladakh; 46 for Kashmir and 37 for Jammu.

The Commission impacted Kashmir. “This changed the intra-state power balance; weakening the preeminent political position of the valley,” wrote Dr HaseebDrabu in September 2013. “In 1989, the Jammu region had 18.3 lakh voters, while Kashmir had 22.2 lakh voters. In a little over a decade, this was reversed. The population of the Jammu region as per the 2001 Census was 43.9 lakh while that of Kashmir was 54.4 lakh. Yet, Jammu had 28.7 lakh voters while Kashmir has only 25.5 lakh voters. Despite the lower population, the 37 constituencies of Jammu have 1.8 lakh more voters than the 46 constituencies in Kashmir. Who engineered this and how?”

Drabu used the Soporeversus Jammu West. In 1987, both had roughly the same number of voters: about 54,000. “Yet, in 2001, the number of voters in Sopore was shown to have increased by just 1 per cent in 15 years. As against this, Jammu West shot up by 177% making it the largest Assembly constituency in the state. How was this achieved and why?”

Right now, when everybody in media and politics (Congress included) is seeking a quick delimitation, people on Srinagar streets are unable to understand how a minority will get enough of seats in a House that it will be able to rule the state?

The 2011 census puts Jammu and Kashmir population at 12,541,302. Of them 6888475 (54.92%) live in Kashmir; 5378538 (42.88%) live in the Jammu region and the balance 274289 (2.18%) are in the arid desert region of Ladakh, now the state’s third administrative division.

In the just-concluded LokSabha polls (see table), the state had an overall electorate of 7484914 voters. The state-level voter to population ratio was 59.68%. But the devil is in the details. In Kashmir, the voter to population ratio was 57.59%. In the case of Jammu, the ratio was 62.06% and in the case of Ladakh, it was 65.34%.

This might explain why the average per berth voter population is lesser (86245) in Kashmir in comparison to Jammu (90227). In an 87-member House, with 46 berths, Kashmir’s percentage representation is lesser (52.87%) in comparison to Jammu which is adequate (42.52%) on the basis of plain demography.

The difference in population between Kashmir and Jammu (2011) is 1509937. The net difference between the electoral rolls was 421855 (2014) and 628884 (2019). What can explain this?

What is more interesting is that in Jammu and Kashmir, electoral rolls for Lok Sabha and state assembly are different. Unlike Lok Sabha, a section of the population in Jammu – the West Pakistan Refugees lack a right to vote in the assembly because they are not state subjects.

The electors for the Lok Sabha and assembly must differ, at least in Jammu. But they are not. For 2014 assembly polls, 3338181 voters were listed in Jammu. In 2019, five years later, the number of voters for Lok Sabha was 3338399. It does not explain anything. There has to be a good difference between the two electoral rolls separated by five years. By the way, where have all the new Jammu voters gone who were enlisted in the last five years? By the way, the electoral office in the state revises electoral rolls every January. So the data poses more questions than it answers.

A New Delimitation

The demand is quite normal and could be considered. Last time when GhulamNabi Azad government reorganised the state by adding more districts, he had plans of changing the number of seats for the assembly as well. Azad invited an all-party conference and suggested a proportional approach – a 25 per cent increase in the existing numbers. Even bills were readied but it did not take off.

Now the delimitation debate is back. But using the delimitation to foresee a change in the governance system of the state is slightly impractical.

“You can have 1000 seats in the assembly but you cannot change the basic characteristics of the state demography which is Muslim majority,” said an academic. “But if you want to change numbers in the regions and sub-regions to dis-empower ethnic Kashmir, it can have long term consequences.”Unlike the Dogra heartland or Kashmir Valley which has a homogenous population, the interventions and manipulations are possible in areas where there is a mixed population like the Chenab valley and parts of the Pir Panchal.

J&K Representation of the People Act gives some weight to geographical compactness, nature of the terrain, facilities of communication and many other things but it cannot be disproportionate to basic demographics.

“It is easy said than done,” said an officer aware of the processes involved. “President will have to invoke his rights to undo what had been done, de-freezing the delimitation. In the second stage, the Representation of the Peoples Act needs an amendment. In the third stage, a delimitation commission is to be set up and then it requires time to move, talk and reach a consensus. That means a couple of years.”

And the bigger question is why delimitation is required in 2019 when the new census is slated for 2021? This makes the entire debate slightly premature. This exercise is legitimate but an election cannot be withheld for this. Or, as many people say, the debate is attention diverter from something that is cooking somewhere. Is it?