With assembly active and no government in place, various politicians are attempting to get power and are keenly exploring the possible loopholes in state’s stringent anti-defection law. Masood Hussain revisits the history of the defection in the state to understand how the conflict has helped the tradition emerge into a sort of institution in itself

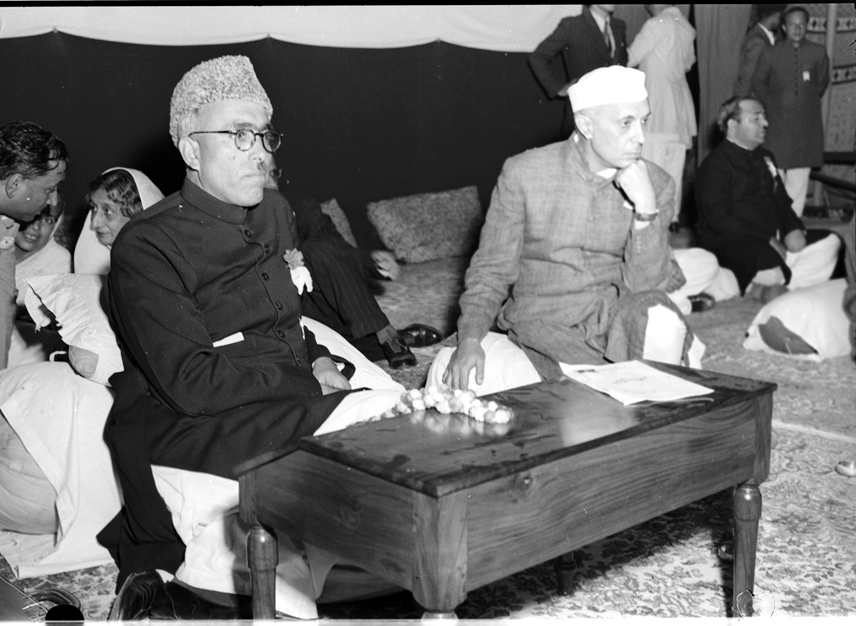

When Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, was arrested by police in Gulmarg on August 8, 1953, not many people stood behind the Sher-e-Kashmir. The only odd man out was Afzal Beg. Sheikh did not get support from any of the 43 ‘lawmakers’ whom he had hand-picked and brought into the constituent assembly unopposed by resorting to a sort of terror that prevented anybody to stand against the National Conference (NC) nominees.

Well before Sheikh would reach Tara Niwas in Udhampur for his imprisonment, Bakhshi, one of his most trusted lieutenants had taken the oath of office as the new Prime Minister. This watershed event would continue dominating Kashmir’s political landscape forever. This was the principal event that laid strong foundation of the institution of defection in Jammu and Kashmir.

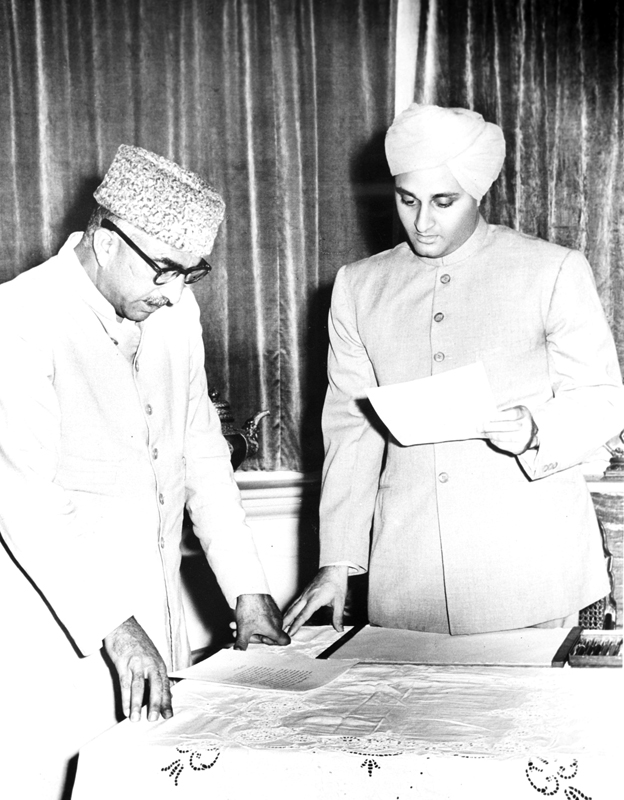

Sheikh was destined to taste it again. In 1975, he returned from 22 years of “political wilderness” and entered into an accord with Indira Gandhi. The Congress was so happy that Sheikh returned as the “Chief Minister” in the least autonomous Congress house that they asked one of its members to resign to pave way for Sheikh’s election and take over as head of Jammu and Kashmir. On February 25, 1975, Mir Qasim stepped down as Sheikh took the oath of office. Congress pulled out the support and the government collapsed on March 16, 1977.

In July 1977, when Sheikh won a landslide victory, one of his first priorities was to legislate on anti-defection. He actually did it. Editor and commentator Mohammad Sayeed Malik was then Director Information. “It was a crude effort but it made Jammu and Kashmir the first state in India to have a law against the defections,” Malik said. “In that era, defection was not even taken cognizance of in the Indian politics.” Lok Sabha passed an anti-defection law in 1985, almost a decade after Jammu and Kashmir.

Sheikh’s anti-defection law gave enormous powers to the Speaker of the assembly and the party presidents and was, as Malik insisted, “sort of a democratic martial law” that would unseat a member if either of the two would issue an order. Quite interestingly, it has an instant target.

In 1977 elections, NC won 47 of the 67 seats. These included Malik Mohiuddin from Pampore and Mian Bashir from Kangan. Later, Mohiuddin became Speaker and Mian a junior minister. Soon, Mian started disliking his status saying he was a major Gujjar leader and should have been a cabinet minister. Finally, the angry Gujjar resigned from the party and joined Congress. NC invoked the new law and Speaker Mohiuddin unseated Mian by an order in June 1980.

Mian filed a writ petition before the High Court challenging the Section 24-G of the J&K Representation of the People Act, 1957, under which he was unseated. In an interesting twist, Mohiuddin was pulled down in a no-confidence motion in October. In quick follow up, he resigned and joined Congress. He faced the same fate under the law. Eventually, he also petitioned the court against the same law.

The petitions were tackled by a constitution bench comprising four judges. Led by Justice Adrash Sen Anand, the bench had two Muslim and two Hindu judges, comprising Bahuddin Farooqi, I Kotwal, and G Mir. The verdict came in the split. Judges Sen and Kotwal ruled the two lawmakers were not disqualified as Farooqi and Mir insisted they stand unseated.

“Again, in Jammu and Kashmir alone, there was a rule called tie-breaker rule,” Malik said. “In split decisions, the senior judge’s decree will prevail so Mian Bashir’s status was restored.” The government went against the verdict in the Supreme Court. His son Mian Altaf who deserted Congress for NC, represents the constituency for the fourth consecutive term but the verdict is yet to come!

After Sheikh’s demise, Dr Farooq Abdullah got a massive sympathy vote as it got 48 of the 76 seats in June 1983. A newcomer, the inexperienced Farooq created a new image for himself and went against Delhi. Soon, he was facing the music as his brother-in-law; Ghulam Mohammad Shah readied himself for replacing him as state’s chief executive.

The plan that Jagmohan supervised on behalf of Mufti Sayeed led State Congress witnessed 12 of Dr Farooq’s lawmakers supporting Shah. On July 2, 1984, Shah took the oath of office as Dr Farooq became an instant opposition leader. It was a drama of democracy in the assembly. “On the day, the floor test was scheduled, two lawmakers Bhim Singh and Abdul Gani Lone were intercepted midway and taken away,” Malik remembers. “Speaker Wali Mohammad Itoo was physically removed from his chair and when he read out the name of the defectors, the new Speaker Mangat Ram Sharma ruled contrary to it.”

Dr Farooq could not forget this. After Indira Gandhi was assassinated and Rajiv Gandhi succeeded her, they came closer. Finally, the Congress withdrew the support to Shah’s government and Farooq was restored as Chief Minister in November 1986. When the NC-Congress alliance retained power through mass rigging in March 1987, Dr Farooq added more teeth to the anti-defection mechanism in the state. But the new government was destined to stay in power for a brief time. By early 1990, Dr Farooq had resigned as the new situation emerged in the state with the onset of militancy. He opposed the appointment of Jagmohan as the governor of the state at the behest of Mufti Sayeed, then India’s Home Minister. For the next six years, Delhi ruled Jammu and Kashmir through its governor’s.

In the 1996 polls in which the security grid used its long arm to drag the people out of their homes to cast their votes, NC got a two-third majority for the first time in history – 57 berths in 87 seat house. When entire Delhi flew specially to Srinagar to oversee Dr Farooq Abdullah taking over as the Chief Minister, everybody in the audience was surprised to see Molvi Iftikhar Hussain Ansari taking the oath of office as a minister. He was a senior Congress leader and without resigning from the party, he became a member of Dr Abdullah’s cabinet. Even Congress did not object to it. In 2002, Molvi resigned from Congress and formally joined the NC, and won from Pattan.

It was in 1999 summer when some Congress lawmakers resigned from the party and floated the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). Molvi joined them in 2006 after resigning from the assembly.

The anti-defection law was in place but there was no requirement of its invocation for a long time. The first time, any government felt the requirement of a strong anti-defection law was that of PDP, led by Mufti Sayeed in 2005. It had apprehensions that its members could be taken over by the ally Congress. The two parties had inked a power-sharing agreement under which Congress would replace PDP as the coalition leader after three years. PDP was unwilling to give up power and feared tensions. In March 2005, when the bill for a stringent anti-defection law was tabled Congress opposed it, tooth and nail.

In the 2005 fall when finally Ghulam Nabi Azad took over the reins of power, the most important thing that was on his mind was the anti-defection law. He was unwilling to run a government with 39 ministers – as Mufti did – and wanted to make the council slightly manageable. But in that process, he had the apprehensions that the disgruntled lot might defect.

Finally, the state assembly passed twin pieces of legislation – one about downsizing the council of ministers and the other amending the anti-defection law, in December 2005.

It was the PDP drafted bill that was reintroduced to amend the law enacted in 1987 by Dr Farooq Abdullah led NC – Congress coalition government. But the bill was passed after NC extended support in the special session of the assembly in the last week of December 2005. The amendment Bill deleted paragraph three of schedule 7 of the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution according to which if one-third MLAs of a party form a separate party, their group gets recognition in the House.

The new law deleted the Para 3 of Schedule 7 of the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution, which earlier allowed one-third of a party’s lawmakers to form a separate, recognised group. Unlike the rest of India, the issue of disqualification of defecting lawmakers is referred to the leader of their own legislature party, whose decision is deemed to be final. Under this law, if applied, the defectors will have to resign first and then join or float a new group.

The new intervention improved the earlier law. Now annoyed legislators not getting ministerial berths cannot revolt. Individual legislators enjoying the one-third support of their parties cannot be recognized by the House. The new constitutional amendment barred a defector from holding an office in the government (as a minister or deputy minister) or a remunerative political position (in the party) for the remaining part of his term. Besides, the amendment would extend in case of a split in a party as well as to the independents.

At the peak of 2008 unrest over the Amarnath land row, PDP pulled out the support. Initially, Azad insisted he will prove his majority in the floor test. This led NC and PDP to quarantine their legislators to prevent horse-trading. Finally, on July 7, 2008, Azad skipped the floor test in a daylong session and submitted his resignation to the governor.

“I stand for clean politics and not horse trading”, Azad told the legislature in an emotional speech. “I made the anti-defection law more stringent not knowing that I would face its brunt”. I know, he said, some of my colleagues in the opposition benches are in a devil and deep sea situation. “Their heart is beating for me but the whips issued by their parties do not want them to go with their conscience. So I withdraw the (trust) motion and resign,” Azad said.

The next time, everybody in the political class was talking about the anti-defection law was in April 2011, when seven of the 11 BJP lawmakers, defied the party whip and voted for ruling NC-Congress coalition in the state’s legislative council polls on April 13. As the party investigated the embarrassing situation, they came to know that former defence minister Chaman Lal Gupta led the 7-member group that cross-voted. Other members included Bharat Bhushan (Domana), Baldev Sharma (Reasi), Prof Gharu Ram Bhagat (RS Pura), Durga Dass (Hiranagar), Master Lal Chand (Bani) and Jagdish Sapolia (Basohli). They were immediately suspended from the party membership.

BJP wrote to the Speaker asking for invoking state’s stringent anti-defection law to tackle the issue. But the ruling NC avoided taking action despite its partner Congress seeking an early decision. NC insiders said the main problem for not going by the book was that invoking the law would mean showing the seven door which would entail having a fresh election. Given the situation on the ground, Congress was in a better position to sweep all the seven. It would have improved Congress’s tally in the state assembly and make it “more dictatorial.” So the Speaker accepted the rival factions (7:4) of the BJP as two separate groups and managed the show for all these years. Gupta’s group later openly supported the ruling coalition in December 2012, in a few LC seats as well.

As the party insisted on action against the fraud, the seven lawmakers planned to float a new party. Gupta’s son Anil has floated Jammu Kashmir Democratic Front (JKDF). This led the Parivaar thinking about the costs that this tension can cost. In run up to 2014 Lok Sabha polls, they were approached, their expulsion was undone and they all were taken back into the party.

Now in wake of BJP pulling out of the coalition without dissolving the assembly, the anti-defection is again back in focus. In fact, Ram Madhav arrived in Srinagar and one of the objectives was to garner the support. Insiders say the anti-defection law was the major obstacle. Now the party says the only saving grace is that Speaker is a BJP man and his ruling cannot be challenged in any court as per the law.

But the larger debate is that the defection and anti-defection do not involve the people at large. It involves only 87 members of the state legislative assembly who are part of a nearly 250-member political class in the state. The overall history of the defection and alliance suggests that the entire pro-India camp, the mainstream, has normally remained open to shifting loyalties.

Sheikh, the towering leader, by all means, was Nehurian Congress’s most trusted man. Post-1953, NC led a serious campaign against the Congress that led to divorces and dead men being buried without funeral prayers. But post-1975, the parties mended fences only to be separated again in 1984. They are still in a tight embrace barring 2002-2008 era. In between, NC sent Omar to the Vajpayee council of ministers where he was the poster boy of External Affairs Ministry.

Mufti was a Congressman, who later joined Janta Dal and returned to Congress, years before he founded his PDP. Post-2014, as the new India was born with Narendra Modi as the leader, Mufti entered into talks and allied with the right-wing party and insisted it was sort of a second accord after the accession.

All other characters have followed the same growth story. The political families have used this growth story as part of their personal ambitions and the show will go on. Individuals who were key in the fall of Dr Farooq Abdullah government in 1984 returned to him and became his ministers again.

There are individuals who are connected with all sides of the ideological divide. Sajjad Lone, who is currently in news for his ambition of being the Chief Minister, is an interesting case. Son of Abdul Gani Lone, who was assassinated as a Hurriyat leader, Sajjad’s brother Bilal is with Hurriyat. His wife is the daughter of JKLF co-founder.

“There is not much of the difference between these parties because the core basic is same,” one political commentator said. “This is almost the same situation that exists on the other side of the ideological divide: one regime in Islamabad loves Mirwaiz more than Geelani and then another regime reverses the trend.”

There are not many barriers between BJP and Congress in Jammu, too. Lal Singh can testify that.

The reality is that these camps and individuals are managed remotely from the power centres in Delhi and Islamabad. Anybody who has defied the dictate has suffered. “Whenever New Delhi feels a leader in Kashmir is getting too big for his shoes, it employs Machiavellian methods to cut him to size,” Syed Mir Qasim, who stepped down as Chief Minister to pave way for Sheikh Abdullah in 1975, has written in his autobiography. Omar, his remote successor, said only last week: “Actually not every MLA is eyeing the top cabinet post as you put it. There are many of us who would not touch it with a barge pole in this assembly. Not all of us are willing to be the intelligence agencies plant in the J&K secretariat.”

So the show will go on with or without anti-defection law.

Masood Hussain Sahib’s each and every piece of journalistic work is a serious and meticulous ornament decorated with excellence. Here honest historians must come up with their comments. I am not qualified for the same. However, it is an excellent informative and educative piece that deserves debate, discussion and honourable shelf in the archives of Kashmir’s Great History. May Allah bestow Masood Sahib’s Pen with more & more CREDIBILITY, IMPACT & MIGHT. Inshallah