by Abrar Reyaz

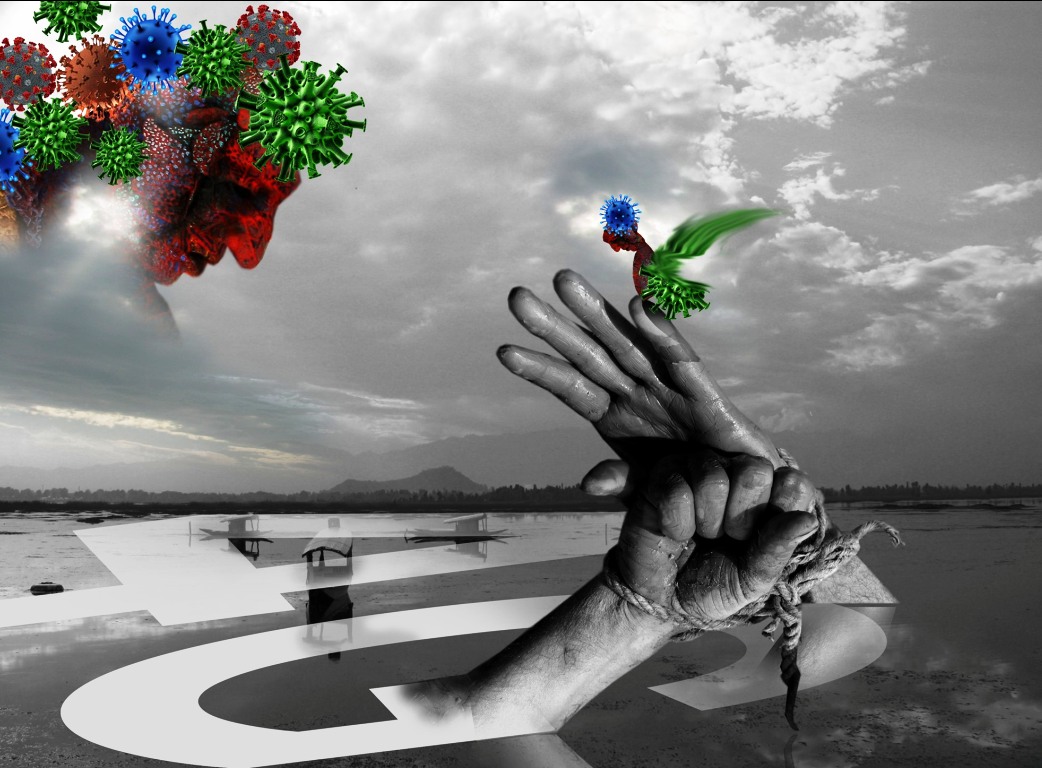

On Monday, April 11, the Supreme Court of India reserved orders (when this column was being written), while hearing a bunch of petitions, challenging internet restriction orders, in Jammu & Kashmir, particularly to enable access to health services and online education during COVID-19 lockdown.

Arguments Advanced

The arguments on behalf of petitioners were put forward by learned counsels, Salman Khurshid, Huzafa Ahmedi and Soayib Qureshi. To my understanding, the grounds on which the impugned orders were challenged and disputed is not going to move and motivate their lordships – the honourable judges of the Supreme Court. Given the fact that national security is a holy cow, and absorbs and eclipses the fundamental rights, in contemporary jurisprudence, the respite is restricted. The legal balance between national security and fundamental rights in this part of the world always shifts towards former and seldomly latter.

Unfettered Power Of State

The most pertinent question, that was altogether missing in the petitions, that could have been raised was, whether the state has unlimited and unfettered power and authority, to keep internet (as a mode of enjoying and exercising a fundamental right, if not fundamental right itself) in abeyance; and put restrictions for a longer period of time, or indefinite period of time.

Restricting Fundamental Rights

The fact of the matter is that the state can’t restrict any fundamental right unless there is a law, which has been passed by the legislature or any rule framed by the executive. The rules made for the purpose of restricting internet speed fall under the Indian Telegraph Act. Those rules are: ‘Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services Rules, 2017’ – which don’t put any cap on a time limit, for putting such restrictions or suspending internet.

Legal Scrutiny

Could this law/rule have been put to face the legal scrutiny and judicial test, given the fact, it is only on declaration of emergency, fundamental rights can be suspended for an indefinite period of time; doesn’t this law then give emergency powers to the state, even in normalcy. It is pertinent to note that emergency remains in force for a period of six months from the date of proclamation. In case it is to be extended beyond six months, another prior resolution has to be passed by the Parliament. In this way, such emergency continues indefinitely.

No Safeguards

The question which should have been raised is, whether the power exercised under this rule, can be possibly misused, exercised arbitrarily, discretionally and on whim and caprice, given the fact, that there is no cap on the maximum time period for putting such restrictions. In Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2019), the Supreme Court of India observed, “the existing Suspension Rules neither provide for a periodic review nor a time limitation for an order issued under the suspension Rules.”

Reasonable Restrictions

Further, reasonable restrictions to fundamental rights are exceptions, and not the law of land itself. The restrictions can’t be put for an indefinite period of time. In Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2019), the Supreme Court of India held that “Any order suspending internet issued under the Suspension Rules, must adhere to the principle of proportionality and must not extend beyond necessary duration.” It is obvious, the parameters observed for suspending internet are applicable to restrictions also (I will come to this part later).

Internet- A Fundamental Right

Coming to the last, but fundamental question, whether the Internet is a fundamental right or means to exercise a fundamental right. It is imperative to say, liberty to exercise right, doesn’t simply connote choice and freedom to exercise such right. It includes within itself, absence of restraint and constraints, and existence conditions that enable you to actuate this choice and freedom.

Absence of restraint and constraint is negative liberty and is necessary to enjoy positive liberty, i.e, freedom to actually exercise the particular right in question (freedom of speech, right to information, right to education, right to health and right to life).

The Supreme Court of India declared in Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2019) that, the freedom of speech and expression and the freedom to practice any profession or carry on any trade, business or occupation over the medium of internet enjoys constitutional protection under Article 19(1)(a) and Article 19(1)(g).

Tailpiece

Even if, the internet is not a declared fundamental right, the speed restrictions over and on it, put restraint and constraint, on the exercise of above-mentioned rights. Whether courts declare, Internet fundamental right or not, the means to exercise fundamental right and providing ways to bring about the existence of conditions to facilitate such right is itself a right (if not fundamental).

(The author is a law student at Department of Legal Studies, Central University of Kashmir. Ideas expressed are personal)