by Mohammad Saalim Farooq

“The individual has always had to struggle to keep from being overwhelmed by the tribe. If you try it, you will be lonely often, and sometimes frightened. But no price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself.”

“The surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

I write these words with a heavy heart and many entangled emotions, desolated, and disgusted with my existence. Yes, I belong to a class of people whose youth live with untrammelled complexes and insecurities. It is not my singular apathy, I perhaps mouthpiece many of those whom you see cheerful yet dejected; sociable yet alone; relentless yet guilt-ridden.

The theatre of our life is directed by two master emotions of anger and guilt; which do not operate differentially, rather act simultaneous and head to head. Their operation synthesizes into a moral dilemma; inhibiting us to an active indecisiveness, which resides long inside our mortal selves.

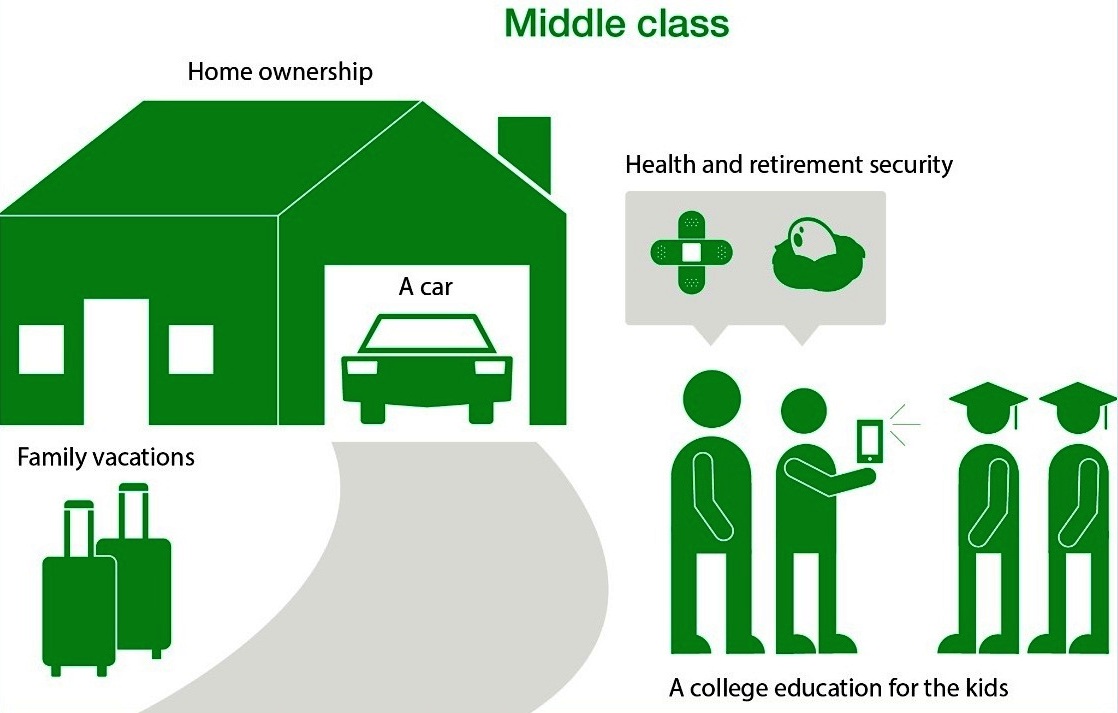

Living life prerequisites certain basic freedoms: like the freedom to a basic standard of life or freedom to acquire a health service; a necessity for human development. Apparently, the middle-class standard of life is privileged to have all decent minimums. We may not be solely dependent on government health services, rather can afford private appointments or –to take from a famous definition of the middle class – may have some basic material amenities like scooter, TV or refrigerator.

Does it make life any simpler? No, on the contrary, it all adds to an already cumbersome life and enriches the complexity of its dilemma. Wondering how? It’s because these basic decent minimums get entwined with an emotional rollercoaster of anger and guilt.

We are encountered with the pleasure of their utility but at the same time, we face the hysteria of its burden, if somehow things do not work out. For example, middle-class parents invest a substantial amount of their savings on education pursuits of their children and if somehow their children are unable to reciprocate with assured success, say, a decent job, entire of this so-called privilege becomes a source of an everlasting sense of inadequacy.

Consequently, we are left with a desperate feeling of guilt, which is exacerbated by a constant injection of the sense of failure. Alas! We fail to live up to the expectations of our paternalistic standards –which makes us believe that, we are solely responsible for some other persons’ choices; be it parents or any other patriarchal authority.

This is where the absurdity of middle-class life gets stripped of its apparent material privileges. While having all the decent minimums, middle-class youth gets depressed by a mere failure, not because we have somehow realized Camus’s existential absurdity of life, rather our social pathology is messed up with belittling and guilt-ridden complexes and our material privileges fail to translate into actual freedoms.

We may be free to have education, health services, decent per capita income, civil and political liberties, and so on, but we are not free to have reasonable choices in our lives or, in Amartya Sen’s favourite terms, we aren’t free to ‘choose a life we have a reason to choose’.

The tragedy is, even after having all the basic utilities; we live a life where guilt is so prominent that our will to live a reasonably good life is rendered empty.

A pressing question is where does this guilt emanate from? And its answer is violence in the pattern of our socialization. But how do we understand this violence? By violence I do not mean, as Hannah Arendt would argue, a ‘distinct form of power, force, or strength [which] needs implements’, rather by violence I mean violation in the sensible trajectory of healthy living. An exemplification of such a violation can be imagining how it feels for a specially-abled person to enter a building without a wheelchair ramp.

Perhaps an entire structure feels like a disallowing guardian willing to throw out this ‘wheelchair ridden pathetic being’. What is happening in the process? A sensible and healthy trajectory of life is being denied to exist. This is where violence lies.

What formulates in response is anger, which is by no means so trivial that one could dispose of easily. It’s rational and is naturally harboured, influencing an individual’s entire life. No material sufficiency can overcome this anger, for until this violent structure persists, it continues to perpetuate from one stage of life to another.

If readers can analogically relate to above-discussed example, they will observe that our paternalistic attitudes of socialization get constantly interrupted by such violations where violent patterns of life are supplemented by doses of moral advice, which somehow make us conform to an unhealthy pattern of life even when we feel it to be wrong.

This attitude becomes so pervasive that it ruins us of our introspective agency. We know that whatever is happening with our life is mentally degrading still we believe this misfortune to be cosmically just and try to seek refuge in the temporality of fortune. This creates a mixture of anger and guilt; we get angry with our interaction with the other (which can be anything animate or inanimate outside of ourselves) but feel guilty to an otherwise natural and rational outcome –which could only be anger.

In simple words, we are advised to be calm but violated of our dignity, where the violation causes anger and advice ushers us with guilt.

Consequently, it feels normal to get ruined of our dignity and still not blame the violator. This is how this violation gets normalized. No wonder, even among the materially well-off middle-class families, many harassment cases remain unreported.

A related question arises that why is it a benign tragedy of middle-class only? It’s because middle-class anxieties yearn for stability in maintaining the acquired standard of life and falsely hope it to come by adjoining its progeny to some tested patterns of life and dismiss any experiment as lethal. Any assertion of individuality gets compromised for the sake of some paternalistic standards to which this class has already conformed. It tries to maintain a fine and it’s hardly achieved the balance between conservatism and freedom. This is why middle-class is not only economically medial but socially too.

Our last question could be: what needs to be done? And for this, ‘I know that I know nothing’. In my opinion, there are no concrete solutions. Can we go on to undo the violent history of our lives? My sole intention is to highlight the problem, rather than give expert advice. Perhaps what we need is to reflect, for ‘we are discussing no small matter but how we ought to live’. (Illustrious Socrates in Plato’s The Republic)

(The author is a post-graduate in Political Science from the University of Kashmir, currently preparing for higher academic studies. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Kashmir Life.)