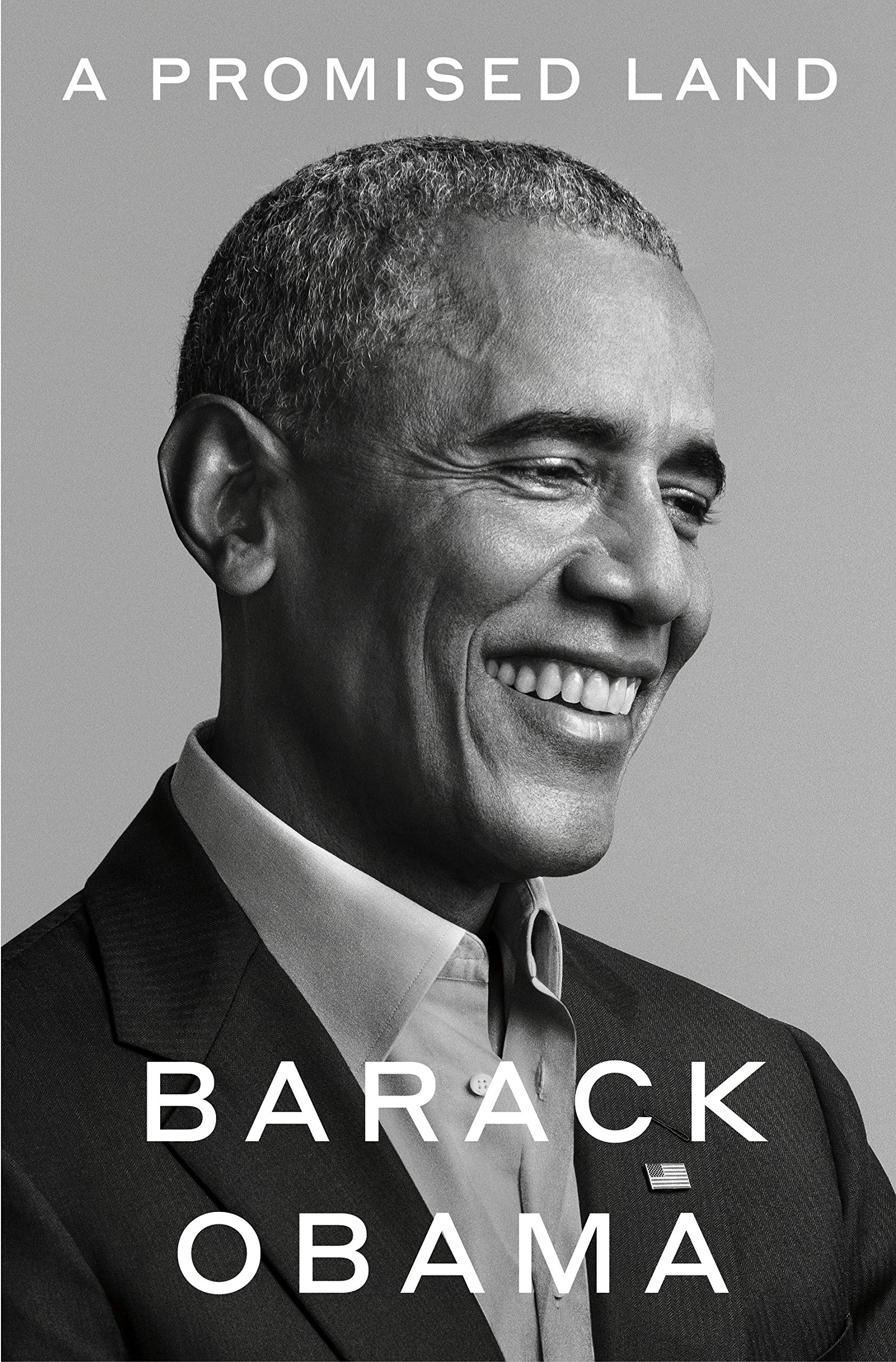

The former US President Barack Obama’s book ‘A Promised Land’ has made a special mention of his first India tour and in between, he had made a series of observations about the leadership and the politics of a nation that owes a lot to the struggle of Mahatma Gandhi.

I’D NEVER BEEN to India before, but the country had always held a special place in my imagination. Maybe it was its sheer size, with one-sixth of the world’s population, an estimated two thousand distinct ethnic groups, and more than seven hundred languages spoken. Maybe it was because I’d spent a part of my childhood in Indonesia listening to the epic Hindu tales of the Ramayana and the Mahābhārata, or because of my interest in Eastern religions, or because of a group of Pakistani and Indian college friends who’d taught to me to cook dahl and keema and turned me on to Bollywood movies.

More than anything, though, my fascination with India had to do with

Mahatma Gandhi. Along with Lincoln, King, and Mandela, Gandhi had profoundly influenced my thinking. As a young man, I’d studied his writings and found him giving voice to some of my deepest instincts. His notion of satyagraha, or devotion to truth, and the power of nonviolent resistance to stir the conscience; his insistence on our common humanity and the essential oneness of all religions; and his belief in every society’s obligation, through its political, economic, and social arrangements, to recognize the equal worth and dignity of all people—each of these ideas resonated with me. Gandhi’s actions had stirred me even more than his words; he’d put his beliefs to the test by risking his life, going to prison, and throwing himself fully into the struggles of his people. His nonviolent campaign for Indian independence from Britain, which began in 1915 and continued for more than thirty years, hadn’t just helped overcome an empire and liberate much of the subcontinent, it had set off a moral charge that pulsed around the globe. It became a beacon for other dispossessed, marginalized groups—including Black Americans in the Jim Crow South—intent on securing their freedom.

in her ‘Kashmiri Gown’ along with Barack Obama

Michelle and I had a chance early in the trip to visit Mani Bhavan, the modest two-story building tucked into a quiet Mumbai neighbourhood that had been Gandhi’s home base for many years. Before the start of our tour, our guide, a gracious woman in a blue sari, showed us the guestbook Dr King had signed in 1959, when he’d travelled to India to draw international attention to the struggle for racial justice in the United States and pay homage to the man whose teachings had inspired him.

The guide then invited us upstairs to see Gandhi’s private quarters. Taking off our shoes, we entered a simple room with a floor of smooth, patterned tile, its terrace doors open to admit a slight breeze and a pale, hazy light. I stared at the spartan floor bed and pillow, the collection of spinning wheels, the old-fashioned phone and low wooden writing desk, trying to imagine Gandhi present in the room, a slight, brown-skinned man in a plain cotton dhoti, his legs folded under him, composing a letter to the British viceroy or charting the next phase of the Salt March. And in that moment, I had the strongest wish to sit beside him and talk. To ask him where he’d found the strength and imagination to do so much with so very little. To ask how he’d recovered from disappointment.

He’d had more than his share. For all his extraordinary gifts, Gandhi hadn’t been able to heal the subcontinent’s deep religious schisms or prevent its partitioning into a predominantly Hindu India and an overwhelmingly Muslim Pakistan, a seismic event in which untold numbers died in sectarian violence and millions of families were forced to pack up what they could carry and migrate across newly established borders. Despite his labours, he hadn’t undone India’s stifling caste system. Somehow, though, he’d marched, fasted, and preached well into his seventies—until that final day in 1948, when on his way to prayer, he was shot at point-blank range by a young Hindu extremist who viewed his ecumenism as a betrayal of the faith.

IN MANY RESPECTS, modern-day India counted as a success story, having survived repeated changeovers in government, bitter feuds within political parties, various armed separatist movements, and all manner of corruption scandals. The transition to a more market-based economy in the 1990s had unleashed the extraordinary entrepreneurial talents of the Indian people—leading to soaring growth rates, a thriving high-tech sector, and a steadily expanding middle class.

As a chief architect of India’s economic transformation, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh seemed like a fitting emblem of this progress: a member of the tiny, often persecuted Sikh religious minority who’d risen to the highest office in the land, and a self-effacing technocrat who’d won people’s trust not by appealing to their passions but by bringing about higher living standards and maintaining a well-earned reputation for not being corrupt.

Singh and I had developed a warm and productive relationship. While he could be cautious in foreign policy, unwilling to get out too far ahead of an

Indian bureaucracy that was historically suspicious of US intentions, our time together confirmed my initial impression of him as a man of uncommon wisdom and decency; and during my visit to the capital city of New Delhi, we reached agreements to strengthen US cooperation on counterterrorism, global health, nuclear security, and trade.

What I couldn’t tell was whether Singh’s rise to power represented the future of India’s democracy or merely an aberration. Our first evening in Delhi, he and his wife, Gursharan Kaur, hosted a dinner party for me and Michelle at their residence, and before joining the other guests in a candlelit courtyard, Singh and I had a few minutes to chat alone. Without the usual flock of minders and note-takers hovering over our shoulders, the prime minister spoke more openly about the clouds he saw on the horizon. The economy worried him, he said.

Although India had fared better than many other countries in the wake of the financial crisis, the global slowdown would inevitably make it harder to generate jobs for India’s young and rapidly growing population. Then there was the problem of Pakistan: Its continuing failure to work with India to investigate the 2008 terrorist attacks on hotels and other sites in Mumbai had significantly increased tensions between the two countries, in part because Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, the terrorist organization responsible, was believed to have links to Pakistan’s intelligence service. Singh had resisted calls to retaliate against Pakistan after the attacks, but his restraint had cost him politically. He feared that rising anti-Muslim sentiment had strengthened the influence of India’s main opposition party, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

“In uncertain times, Mr President,” the prime minister said, “the call of religious and ethnic solidarity can be intoxicating. And it’s not so hard for politicians to exploit that, in India or anywhere else.”

I nodded, recalling the conversation I’d had with Václav Havel during my visit to Prague and his warning about the rising tide of illiberalism in Europe. If globalization and a historic economic crisis were fuelling these trends in relatively wealthy nations—if I was seeing it even in the United States with the Tea Party—how could India be immune? For the truth was that despite the resilience of its democracy and its impressive recent economic performance, India still bore little resemblance to the egalitarian, peaceful, and sustainable society Gandhi had envisioned. Across the country, millions continued to live in squalor, trapped in sun-baked villages or labyrinthine slums, even as the titans of Indian industry enjoyed lifestyles that the rajas and moguls of old would have envied. Violence, both public and private, remained an all-too-pervasive part of Indian life. Expressing hostility toward Pakistan was still the quickest route to national unity, with many Indians taking great pride in the knowledge that their country had developed a nuclear weapons program to match Pakistan’s, untroubled by the fact that a single miscalculation by either side could risk regional annihilation.

Most of all, India’s politics still revolved around religion, clan, and caste. In that sense, Singh’s elevation as prime minister, sometimes heralded as a hallmark of the country’s progress in overcoming sectarian divides, was somewhat deceiving. He hadn’t originally become prime minister as a result of his own popularity. In fact, he owed his position to Sonia Gandhi—the Italian born widow of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the head of the Congress Party, who’d declined to take the job herself after leading her party coalition to victory and had instead anointed Singh. More than one political observer believed that she’d chosen Singh precisely because as an elderly Sikh with no national political base, he posed no threat to her forty-year-old son, Rahul, whom she was grooming to take over the Congress Party.

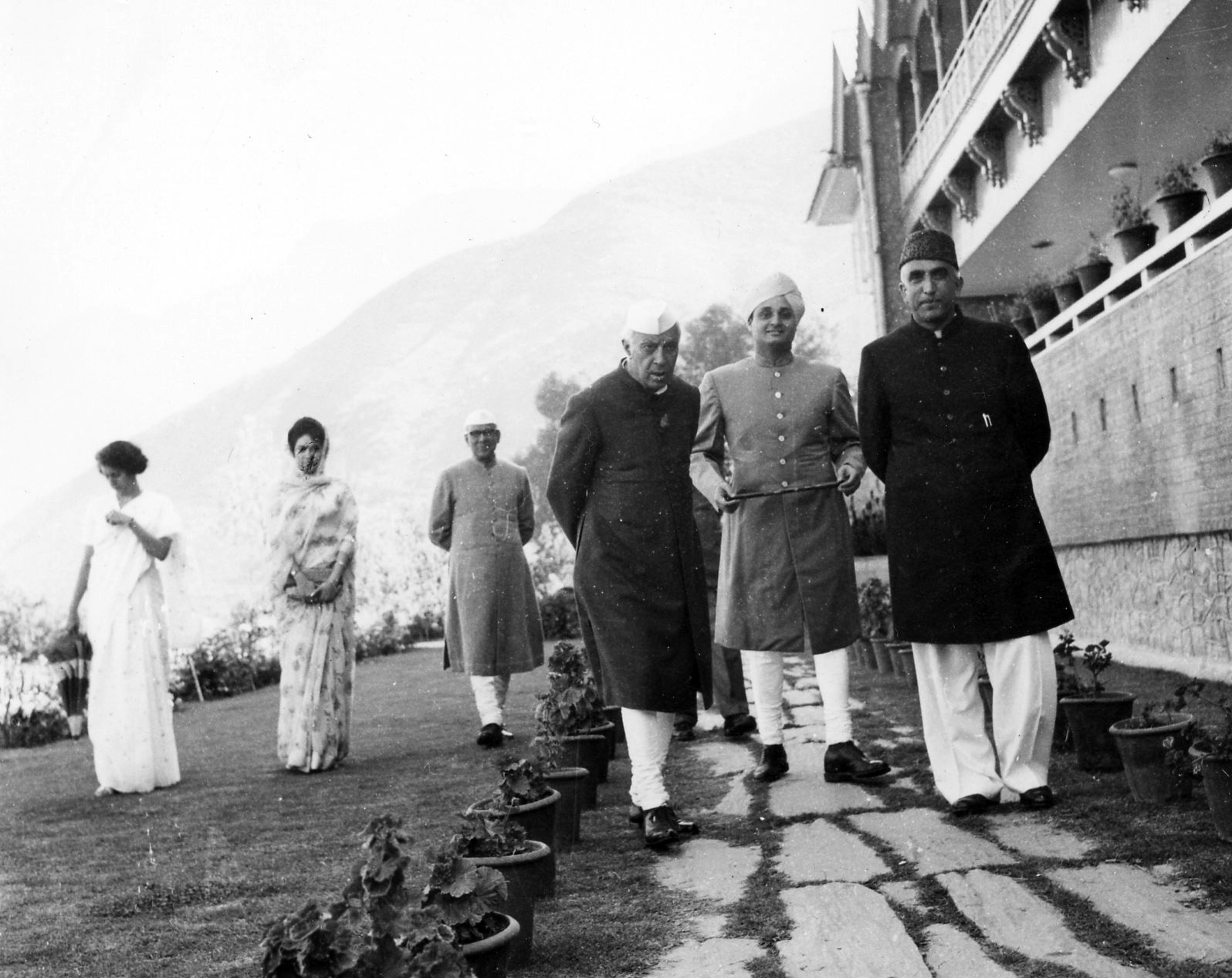

Both Sonia and Rahul Gandhi sat at our dinner table that night. She was a striking woman in her sixties, dressed in a traditional sari, with dark, probing eyes and a quiet, regal presence. That she—a former stay-at-home mother of European descent—had emerged from her grief after her husband was killed by a Sri Lankan separatist’s suicide bomb in 1991 to become a leading national politician testified to the enduring power of the family dynasty. Rajiv was the grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister and an icon in the independence movement. His mother, Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, had spent a total of sixteen years as prime minister herself, relying on a more ruthless brand of politics than her father had practiced, until 1984 when she, too, was assassinated.

At dinner that night, Sonia Gandhi listened more than she spoke, careful to defer to Singh when policy matters came up, and often steered the conversation toward her son. It became clear to me, though, that her power was attributable to a shrewd and forceful intelligence. As for Rahul, he seemed smart and earnest, his good looks resembling his mother’s. He offered up his thoughts on the future of progressive politics, occasionally pausing to probe me on the details of my 2008 campaign. But there was a nervous, unformed quality about him, as if he were a student who’d done the coursework and was eager to impress the teacher but deep down lacked either the aptitude or the passion to master the subject.

As it was getting late, I noticed Singh fighting off sleep, lifting his glass every so often to wake himself up with a sip of water. I signalled to Michelle that it was time to say our goodbyes. The prime minister and his wife walked us to our car. In the dim light, he looked frail, older than his seventy-eight years, and as we drove off I wondered what would happen when he left office. Would the baton be successfully passed to Rahul, fulfilling the destiny laid out by his mother and preserving the Congress Party’s dominance over the divisive nationalism touted by the BJP?

Somehow, I was doubtful. It wasn’t Singh’s fault. He had done his part, following the playbook of liberal democracies across the post–Cold War world: upholding the constitutional order; attending to the quotidian, often technical work of boosting the GDP; and expanding the social safety net. Like me, he had come to believe that this was all any of us could expect from democracy, especially in big, multiethnic, multi-religious societies like India and the United States. Not revolutionary leaps or major cultural overhauls; not a fix for every social pathology or lasting answers for those in search of purpose and meaning in their lives. Just the observance of rules that allowed us to sort out or at least tolerate our differences, and government policies that raised living standards and improved education enough to temper humanity’s baser impulses.

Except now I found myself asking whether those impulses—of violence, greed, corruption, nationalism, racism and religious intolerance, the all-too-human desire to beat back our own uncertainty and mortality and sense of insignificance by subordinating others—were too strong for any democracy to permanently contain. For they seemed to lie in wait everywhere, ready to resurface whenever growth rates stalled or demographics changed or a charismatic leader chose to ride the wave of people’s fears and resentments. And as much as I might have wished otherwise, there was no Mahatma Gandhi around to tell me what I might do to hold such impulses back.

(These passages were excerpted from Barack Obama’s book A Promised Land that was published by Crown Publishing Group in the United States and Viking in the United Kingdom)