An otherwise antibiotic and antioxidant, Garlic coming through the trans-LoC trade has become a headache for the government of India. R S Gull reports on what forced the government to halt the garlic inflow.

Six months of cross-LoC trade in Jammu and Kashmir have emerged as a garlic-onion story. Though 21 items are approved for intra-Kashmir (barter) trade from two crossing points at Uri and Poonch, all with zero duty, it is garlic imports and onion exports that were ruling the roost. As the spice (garlic) became 90 per cent of ‘imports’ in barter of ‘onions’ and the mainland traders from India and Pakistan almost took over the ‘trade’ using surrogates, Delhi took the pathogen cover to halt garlic movement. “It is garlic here (Jhelum Valley Road) and garlic there (Chakan da Bagh),” a senior government official said. “In just two days traders from Poonch and Jammu imported 395 tons of garlic and obviously such a huge quantity is not consumed in J&K.”

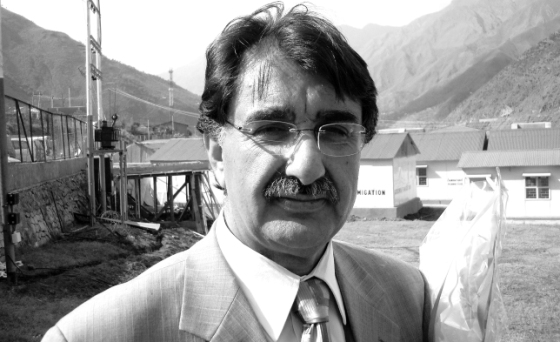

In return, the traders – mostly in Poonch, are sending onions. Officials in Trade Facilitation Centre (TFC) Poonch said in two days last week, traders sent 289 tons of onion. “They import garlic at a much cheaper cost and send onion (at Rs. 9.25 per kg) which fetches their counterparts across Rs. 25 per kg,” one official said. “Eighty per cent of business is garlic and onion. Nine of 12 traders are exporting onion and barring a few almost everybody is sending garlic in exchange.” Adds Mohammad Ashraf Mir, the trade facilitation officer at Uri: “In last five turns, the garlic formed eighty per cent of the imports and on Monday last it was not less than 95 per cent of the total imports.”

The same day, however, the state government received an advisory from the Union Agriculture Ministry’s Directorate of Entomology advising against accepting garlic consignments. It said that certain consignments had exotic pathogen Embellisia Allii infection. “We have been strictly advised against receiving garlic consignments,” said Mir. They did permit the convoys from across but did not unload the garlic that actually was laden in 62 of the 64 trucks.

The trade across the LoC was permitted in October last after months of agitation triggered by the economic blockade of Kashmir by Jammu during the controversial Amarnath land transfer row. Though 21 items produced and manufactured by people on either side of the LoC were approved with a promise of review after every quarter, the trade was reduced to age-old barter in absence of banking relations, telecommunications and a dispute resolution set up.

Euphoric traders in Srinagar initially sent scores of truckloads of apples and other items but failed to realize any money. They wanted something in exchange but did not know what is worth import. And finally, when they identified certain items, the absence of a telephone link emerged as a barrier. “Using e-mail, we imported certain items but it lacked proper packaging,” Altaf Ahmad, one of the traders who handled most of the initial imports in Srinagar said. “These issues could have been sorted out but the trade delegation from Srinagar is yet to be permitted.”

As traders developed cold feet, an ‘era of the cousins’ began. Members of divided families across the ceasefire line started trading. “Since it was plain barter and required absolute trust, the families got involved and the trade somehow survived,” said Mohammad Ashraf Wani, the trade facilitation officer at Uri.

Then came a sudden spurt in imports; most of it garlic. It was the Salamabad-Chakothi Traders Union (SCTU) that disclosed the secret of the sudden spurt. They said the real local traders had been pushed out as the government officials in league with major business houses in Delhi and Punjab had appointed local surrogates who send and receive consignments. With Sheikh Tariq’s SCTU unfolding the real story, the method in the madness became clear.

Garlic prices are soaring in Delhi and elsewhere because of poor arrivals from key growing states of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. Part of the demand is met by cheap imports from Pakistan via Wagha but it costs more because of customs duty. “For every truck, the custom duty is Rs 150 thousand,” says Dr Mubeen Shah, President Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry. “By now, I believe the traders who have their agents working in Srinagar and Jammu might have made a net saving of around three crore rupees on custom savings alone.” And interestingly the garlic being imported via LoC is not being grown in Pakistan, it is Chinese.

The timely intervention of the Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industry saved the situation, at least for the time being. “As soon as we were told that garlic has been stopped and trucks are not being unloaded, we rushed and ensured the investments our traders have made did not go waste. The government will permit unloading of the consignments this time,” Shah told Kashmir Life. But he is not aware of the subsequent follow-up.

On the larger issue of garlic trade, Dr Shah suggests. “Instead of using surrogates and agents, why not local genuine traders import and then auction the same in local vegetable markets. Let the major business houses purchase it and take it wherever they want.” This, he believes, is the only way out for preventing the misuse of zero-duty trade.

Last week consignment of 62 truckloads of garlic belonged mostly to genuine traders. Being a path-breaking initiative, the trans-LoC trade is more hype than trade as it does not make even a fraction of formal trade between India and Pakistan through the Attari-Wagah land route. By the end of March (2008-09), Indian exports to Pakistan were of the order of Rs 463.38 crores as compared to imports worth Rs 53.08 crore. The figures for the previous year (2007-08) were Rs 174.10 crore for exports and Rs 51.79 crore for imports.