After the insiders at the state-run Handloom Development Corporation allegedly stole half a dozen prized shawls with classic designs – revived after huge efforts – and replaced them with ordinary ones, Masood Hussain laments over the lows that Kashmir’s heritage sector is forced to survive with

Empress Josephine, the wife of Napoleon, shall remain the Cashmere darling forever. The trend she set for the Kashmir shawl might have helped Kashmir’s exploitative rulers to fill their coffers but she made Cashmere universal. Not many people know that her fascination for the Kashmir masterpiece started with hate.

“Ugly and very expensive, but light and warm,” Art historian Isabella Campagnol Fabretti quotes the empress writing to her son after receiving the Kashmiri shawl shipment from Egypt where French troops were stationed for three years since July 1798, on blog Couture16. “I have serious doubts that this fashion will last.”

But once she fell in love with the Cashmere, “she would spend as much as 20,000 gold francs for a single shawl” and amassed more than 400 shawls. She set the trend for ‘cashmere mania’ on the Paris high street of fashion and the shawl became so prized possession that “some women went so far as to steal them during court events”. British newspaper Morning Post reported a robbery of “a valuable shawl” from a military wife in 1841 indicating it was so prized that it could make news and, probably, a police case. An essential part of the wedding trousseaux, Napoleon gifted 17 Cashmere shawls to Marie Louise, his second wife in 1811.

As the Cashmere shawl became a fashion statement, the demand soared. In Kashmir, this led to the emergence of rafugars. These expert darners would sew two pieces of shawls in one after they were weaved separately. But that was not the only development that shawls enforced in the market.

As supply-demand chain failed to exhibit a balance and the French middle class also aspired to have a shawl, French straw-hat maker Joseph Marie Jacquard invented his famous Jacquard loom in 1804. It started creating the replica of the Kashmiri shawls to manage the mass market that ruling elites had helped create.

Kashmir shawl had ‘invaded’ France, London, and Russia almost at the same time, by the fall of the eighteenth century. By the time the French troops purchased the Kashmir Shawl in Egypt, the officials serving the East India Company went home with Cashmere for their wives and daughters. Limited supply led local enterprise to get in and they started creating their own limitations.

“The problem was that Kashmiri weavers, working on primitive looms and organised in inefficient ways, were unable to meet this new demand,” Vikram Doctor wrote in The Economic Times. “As a result, the British had to manufacture imitation shawls in towns like Paisley, Scotland and in time, these became so good that their name became synonymous with Kashmir shawls.”

“As early as the 1770s, however, British imitations of Kashmiri shawls began to appear, produced first in Edinburgh, then in Norwich, and then most significantly, in Paisley,” Art historian Kristina Molin Cherneski writes in her scholarly paper Likely To Continue As Fashionable As ever: Kashmiri Shawls, Luxury and The British Empire. “Paisley came to dominate the British shawl trade – the name of the town even became synonymous with the pinecone patterns that were originally associated with Kashmiri shawls and were subsequently appropriated and imitated by British manufacturers.”

“In England, cashmere shawls were produced in Norwich while the textile industry in Paisley, Scotland, could count on agents in Kashmir to send new designs weekly for the printed (and very economical) copies of the shawls woven in Paisley that were to be found in London stores a week later,” according to Isabella.

The two interventions – the loom and Paisley imitations were hugely successful in reducing the costs of the shawl. At a time when Cashmere was selling almost 100-pound sterling’s a piece, Isabella has written that imitations would sell anywhere between 12 pounds to 17-27 shillings, each.

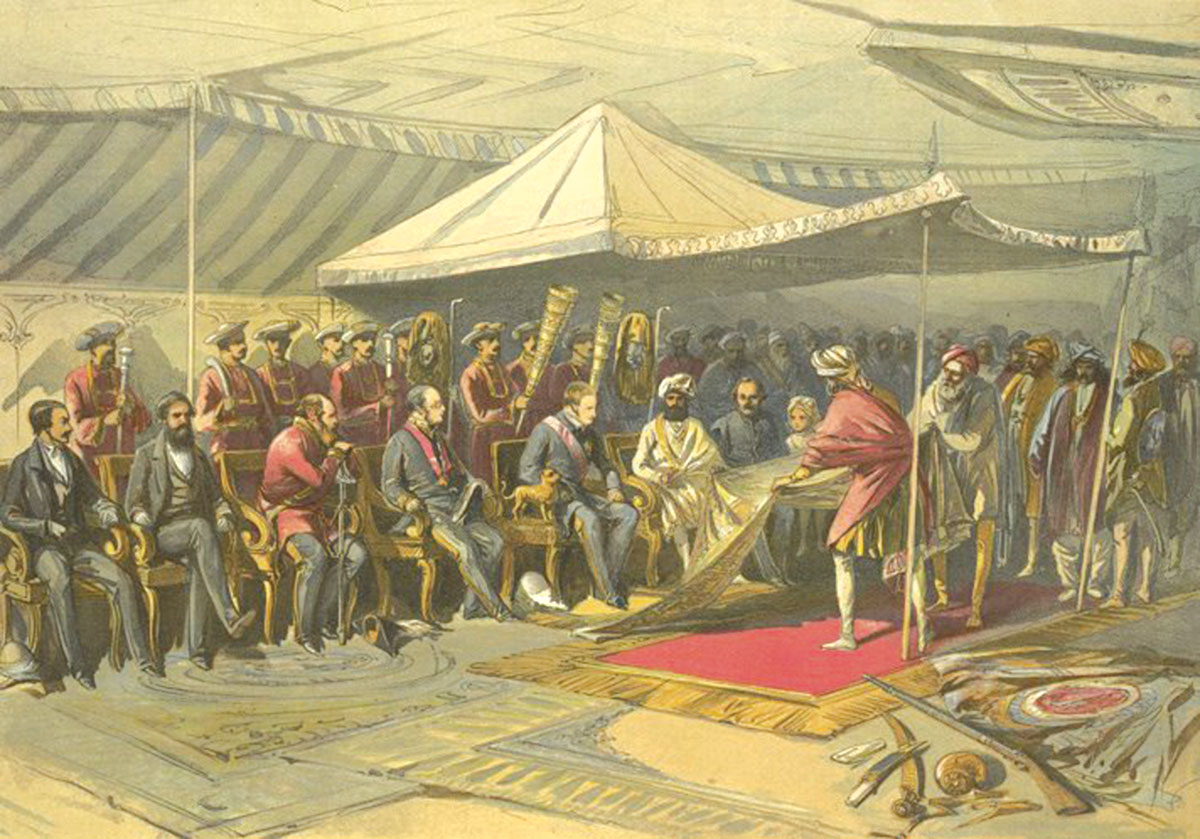

Kashmir shawl has ruled the global fashion for centuries. Recorded history suggests that Kashmir would send shawls to Chinese rulers as early as 1330. People created their own styles with the shawl: Egyptian men created turbans out of it; Iranian women stitched it into their jackets; in Turkistan, men wore Shawl coats; Tibet used it as sashes in and the tradition of gifting it as Khilat – introduced in pre-Mughal era, continued throughout in the ruling class from Delhi to Istanbul. In Kashmir, it still exists. Janet Rizvi has created an impressive narrative of Kashmir’s historic fashion statement in her Pashmina: The Kashmir Shawl and Beyond.

Two centuries later, it seems the shawl has come a full circle as the history has started repeating itself, almost in “reverse swing”. All the interventions that others did are now being done by Kashmiris’ themselves, voluntarily and consciously with the same objective – to make more money. Now, Kashmir shawl is just a commodity but not an economy. It is just a trade but not the same heritage that led kings to wage wars and possess Kashmir.

Kashmir has already done to the Shawl what British, French and Austrian entrepreneurs did – resorted to low-cost imitations. Most of Kashmir’s shawl manufacturing has shifted to Punjab’s textile hubs. The women in Kashmir have given up the wheel and are desperately seeking white colour jobs. The Sozni is now restricted to certain pockets as the least remunerative craft is pushing artisans to alternatives. Traders are facing huge cases across the world for not supplying what they had taken orders for. A lot of inventory is blocked because imitations are not making the money, Kashmir made two centuries back. Willingly and voluntarily, Kashmir has given up a prime heritage, a craft that had given it a global identity.

Take for the institution of Khilat. It is still in vogue in Kashmir, albeit in a different form. At the end of their tenures, the families of some Chief Ministers are used to make a bulk sale of these gifts. Nobody knows if they are real Pashmina or the fake manufactured in Punjab. Emperor Aurangzeb retained the system of Khilat but its quality had deteriorated as was his empire. In normal Kashmir functions, it is happening literally.

The last Khilat that made news was when Prime Minister Narendra Modi, at a White House dinner, gifted Donald Trump a Kashmiri shawl in August 2017. “A journalist noted that this happened soon after a young shawl maker named Farooq Ahmed Dar in Kashmir had been tied to an Army vehicle as a human shield,” Vikram Doctor wrote. “She wrote that “offering his very means of livelihood as a gift to the heads of state in other parts of the world” was not a matter of grave concern.”

This is happening even after a serious effort was launched by the government at revival. The major crisis that Kashmir faced in revival was that it lost all the classics – as the key designs stopped in circulation. Most of the prized shawls were Kani shawls, involving multiple weavers who would use twill tapestry to create masterpieces in many months, sometimes in years. These shawls were costly. Though still being weaved in Kashmir, the level of master-craftsmanship lacks comparison to the proud past.

“In around 1994, we started hunting for the classic designs that had faded from the market,” Mohammad Salim Beg, who was involved in the process, said. “A campaign was launched to identify the places where the masterpieces were and 25 designs were traced and their taleem was generated.” Taleem is the peculiar language of the design that only the artisans can read and implement.

These classic designs were essentially from the Mughal period, because, as Beg says, nothing much was added to the design part till Dogra era. It was only in the nineteenth century that French merchants and Company officials travelled to Kashmir and Punjab regions “to direct the work of the weavers toward European preferences.”

Designs from Mughal, Afghan, Sikh and Dogra eras were collected from diverse sources including private persons in Srinagar, Varanasi, Hyderabad, London, and Paris. The emphasis remained on floral designs or small borders and bright colours, typical of those periods. The process began in 1995. Most of the designs came from Kashmir’s own Design School, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Bharat Kala Bhavan in Varanasi and the Museum of Indology in Japiur. Some were traced in rare history books and converted into taleem.

In the second stage, a hunt was launched to trace the master craftsmen who can actually implement them. The officials at the Handloom Development Corporation – that spearheaded the impressive project, did trace the artisans of eminence and paid them adequately and the project started implementing.

“Since the Kani technique was expensive and markets were not also supportive of it, the idea was to implement these original Kani designs into sozni,” Beg said. The embroidery was adopted to reproduce the traditional butis (pine cone) and floral motifs with a finesse that cannot be matched by contemporary Kani looms. “It proved a super hit.”

Once ready, the corporation flew the revived classic – the Royal Pashmina designs, directly to the buyers in Delhi. It was received well. In an exhibition in Delhi in 1999, a Khatraaz shawl sold for Rs 1.50 lakh and the booking exceeded thirty lakh rupees in the first exhibition. Buyers chose the masterpiece, paid in advance and the product was made and delivered many months later.

“We selected 600 designs and implemented 250. There were 11 series that we revived, and two I supervised, and nine were taken up later by the Corporation.” Beg said. “We actually took these designs to Paris for the exhibition.”

Interestingly, this effort came almost a decade after the Textile Museum in Washington put a huge display of its woollen textiles from Kashmir that was created in 300 years.

The July 1986 exhibition The Scent of Flowers: Woollen Textiles from Kashmir eventually displayed 41 textiles. These masterpieces had been collected by George Hewitt Myers, the Textile Museum founder, from Kashmir in the 1920s.

While these masterpieces were being displayed, the buyers would make their choices. These shawls remained in the inventory of the corporation. Now reports said the officials in whose custody these shawls are have resorted to theft.

“In the last week during the visit of Kashmir Government Arts Emporium to the Handloom Development Corporation’s Central Store at Solina Rambagh, Srinagar for selection of highly expensive Royal Pashmina Shawls and Kani Jamawars, it has surfaced that 3 (three) Royal Pashmina Shawls and one Kani-Jamawar is replaced by inferior shawls,” a formal representation by Corporation staffers to the Principal Secretary (Industry) reads. The representation dated October 15, 2018. “The issue regarding misappropriation of the shawls has been taken up with the Managing Director with a request to hand over the case to Crime Branch J&K for unearthing the scam.”

The representation dropped broad hints about what might have happened to the prized possession in the aftermath of the 2014 floods. They said they had informed the government but “no corrective measures were taken.”

Even though almost half of the year is over, no investigator has taken the cognisance of it! By now, the numbers have gone up: six royal Pashmina shawls have been replaced, along with two Jamawars and five commercial shawls.

In 1841, a theft from a soldier’s wife triggered a police case. In 2019, a robbery by the custodian of the craft is not even cognizable!