The Jammu and Kashmir administration is set to make the endangered Kashmir flycatcher its official bird. Haseeb A Drabu writes why Bulbul will be a more appropriate choice

Prior to August 5, 2019, the official state bird of Jammu and Kashmir was the black-necked crane. Found only in the arid geography of Ladakh, this rare and exotic bird is essentially an inhabitant of the Tibetan plateau. With Ladakh a Union Territory (UT) on its own, there is a need to designate a new state bird; perhaps more appropriately, a UT bird. Not that it is the most pressing and critical task at hand, but good to think about it before we wake up one fine morning to discover that the flamingo has become the new UT bird of Jammu and Kashmir.

The universally accepted criteria for designating a state bird is that it should be found in the state, be rooted in its history and culture and ideally be exclusive. However, ornithologists and wildlife conservationists have been advocating that these honorific titles be given to such birds (and animals) which are either rare or vulnerable to extinction. From a conservation perspective, it makes perfect sense as this official status helps focus attention on protecting the bird or the animal. As indeed it did happen, to some extent, in the case of the beautiful and unique Hangul, which is, and should continue to be the state animal of Jammu and Kashmir.

Hopefully Jammu and Kashmir, like all other sub-national entities, will have a “state subject” – as its official bird. If indeed that will be so, which one ought it to be? Given the situation in the region, it might be more relevant and effective to make the selection from a cultural rather than a conservationist perspective.

Bielbichur

From a cultural perspective, the only bird which is deeply embedded in the literature of Kashmir – prose, poetry, folk takes — is the bulbul, our very own bielbichur. Even in the crafts, especially in papier machie, sozni and ari work– bulbul is a prominent and much used motif. Indeed, many designs like the hazaar dastaan are named after it.

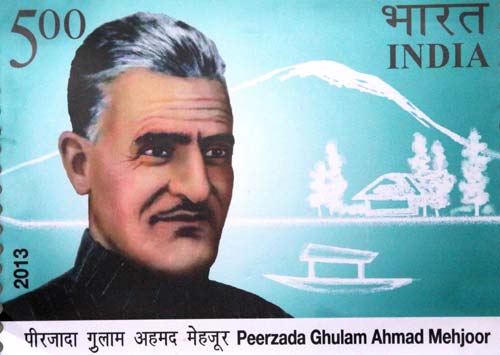

Undoubtedly it was the Shayar-e-Kashmir, Ghulam Ahmed Mehjoor who elevated the bulbul, conventionally a romantic icon to express Kashmiri emotions at a social, political and psychological level. Many others too have used the bulbul as the witness or the messenger. At one level, Mehjoor sees the bulbul gleefully singing in a blooming garden as the culmination of rebuilding Kashmir. He made it the ethereal mascot of a joyous and prosperous Kashmir; a state that we all yearn for, each in our own way.

Undoubtedly it was the Shayar-e-Kashmir, Ghulam Ahmed Mehjoor who elevated the bulbul, conventionally a romantic icon to express Kashmiri emotions at a social, political and psychological level. Many others too have used the bulbul as the witness or the messenger. At one level, Mehjoor sees the bulbul gleefully singing in a blooming garden as the culmination of rebuilding Kashmir. He made it the ethereal mascot of a joyous and prosperous Kashmir; a state that we all yearn for, each in our own way.

Valo haa baagvaano navbahaaruk shaan paade kar,

Pholan gul, gath karan bulbul tithee saamaan paadaa kar

(Arise O, gardener ! Create the glory of new spring,

Make flowers bloom and bulbuls sing – create such haunts)

Then, communicating a political message by comparing the status of a Kashmiri in the 1940s to that of a caged bulbul, he wrote,

karee kus bulbulaa.

aazaad panjaras mans tsu naalan chukh,

tsu pananye dasta pananyan mushkilan aasaan paadaa kar

(Who will set you free, captive bird,

Crying in your cage? Forge with your own hands

The instruments of your deliverance!)

Unlike Falcon

Of course, all this imagery and the literary-romantic perception is not indigenous to Kashmir. It has drawn inspiration from Persian literature. But unlike in the Persian poetry where in the gul-o-bulbul theme the “bulbul and the rose in time’s garden symbolise the eternity of love”, Kashmir poets have used it to evoke a sense of hope and belonging.

All this is in sharp contrast to the Shaheen (falcon); a symbol of self-assertion, and confident self-realisation with a spirit of idealism and action in Allama Iqbal’s poetry. In comparison, the bulbul is attributed less arrogance and attitude, but more prestige and perseverance. The bulbul is also far more a social bird than the falcon who soars high but alone. Which is why, it seems, for Kashmiris bulbul became a harbinger of change. Someone who announces the new order and is also a witness to it. Also, the bulbul not only sings in joy as the rosebuds blossom, it also laments the loss on the rose petals being mauled and scattered, unlike other birds.

Not that the bulbul is unique to Kashmir; they are found all over Asia, Africa and the Middle East. What makes it special for Kashmiris is the imagery built around it; the emotion that has been vested in the bird. The literary equivalent of this cross-continental bird in Kashmir’s poetry, prose and craft, is what makes it Kashmiri. By transforming the sentiment of the mystical poetry from the gul-o-bulbul theme of bulbul’s longing for the rose which served as a metaphor for the soul’s yearning for union with God, Kashmiri poets used it to denote good news, freedom and prosperity for the collective.

The Bulbul Shah

It is no coincidence that the sufi master of the Suhrawardi silisla who converted Rinchin, ruler of Kashmir, to Islam, Sayyid Sharafu’d-Din, was popularly known as Bulbul Shah. He is the one who built the first mosque of Kashmir from the revenues of a few villages granted to him by the King who also built a Khanqah for him near his own palace. Till today, a number of places like Bulbul Lanker or Bulbul Bagh are named after him.

In his collection of allegorical parables, The Conference of the Birds, Attar, whom Rumi called the spirit and himself its shadow, uses the bulbul to communicate an important lesson which is relevant in the current context: those who are trapped in their own dogma, clinging to hardened beliefs or faith, are deprived of the journey towards the ultimate destination. For the bulbul, its love for the rose is a hurdle in the way of going on the journey to seek the Simurgh, the source of all divine enlightenment. Eventually, the hoopoe manages to convince the bulbul and all other birds to make the pilgrimage.

So it shall be in Kashmir too. The only problem, as stated by Mehjoor, being:

Bulbulan Dup Gullas Husn Chui bar pur,

Keyha wanai, zew chai ne, su chui kasur

(Said the bulbul to the tulip, your beauty is boundless,

But, the fault lies in your muteness.)

Tail Piece

In a quotidian context, bulbul is given a tad more affection and respect than, say, a sparrow. Crows, on the other hand, are quite disliked. If a slightly noisy or large crow was ever sighted, it was promptly shooed way and declared to be from Punjabi! Some fierce-looking ones were called the panchael kaaw, with their ancestry being traced to the ancient region of Pañcāla in India!

Again, Bulbul is a prominent presence in everyday language. In many a folk song, bulbul is the main protagonist. For instance, Dari pyath bulbul pichan, Toate shyaad yoor sakhran (On the window sill, chirps the bulbul, the loved one is on way). Or how a sufi minded person is described as some who is Kheane bulbul, pakne paez, gandne gosain, (like a bulbul in eating, a partridge in walking, and a sadhu in clothing).

But it is a plebeian parable of the parrot and the bulbul which hits the ball out of the park for this debate. Dapaan, when a parrot started flaunting his colourful palette of feathers, the dull-looking mouse-coloured bulbul looked at the swathe of his bright canary yellow posterior, and gave the parrot a disdainful glance, as if saying, ‘we use colours to wipe ourselves clean!

(The opinion appeared first in The Greater Kashmir.)