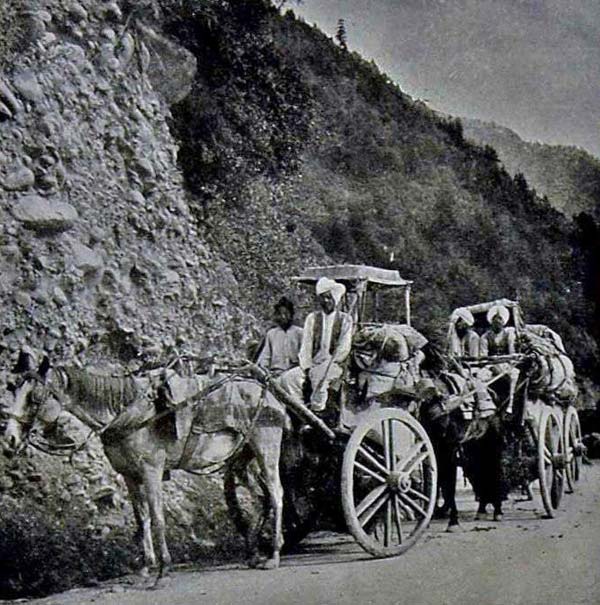

The early twentieth century, horse-driven Tonga became the main public transport for Kashmir. Then the horses would come from Kabul and the carriages from Rawalpindi, a status that Punjab got post-1947. Shams Irfan met the son of Kashmir’s main Tonga dealer to record the carriage’s history from Jhelum Valley Road to the Bollywood films and now to history books

A small two-storey modest house, which once had a large courtyard, where Mohammad Sultan Kosghar, a horse and Tanga merchant, maintained an expensive stable, now stands dwarfed by its prosperous neighbours in Srinagar’s Nawa Kadal. All that remains of Sultan’s legacy is a decorated Tanga – a horse-drawn two-wheeled carriage, which his son Noor Mohammad Kosghar, 70, rents out for marriages and film shootings to earn his living.

The story of the Kosghar’s is akin to the story of Tangas (also written Tonga) and horses, once a luxurious mode of transportation owned only by the elite. Both, the house and Tangas are now out of the memory and fashion.

Sitting in a corner of his drawing-room, Sultan’s son (second among five sons and four daughters) Noor Mohammad, who carried forward his profession and legacy, recalls the heydays of his father’s trade. “My father was one of the most sought after Tanga merchants in pre-partition days,” said Noor Mohammad nostalgically.

The Rawalpindi Era

In the 1930s, Noor’s father Sultan, then young and energetic, along with his seven-workers, made his first journey to Rawalpindi (now in Pakistan), then famous for making high-end luxury Tangas, to start his trade. “He used to tell us stories about his travels,” recalls Noor Mohammad.

After six days of the tiring journey via Baramulla, a transit town in north Kashmir, when Sultan reached Rawalpindi, he placed an order for his first set of Tangas to a local manufacturer.

Then Sultan, along with his men, left towards Afghanistan to get best of the horses for his Tangas. “That is how the business of buying and selling Tangas and horses started in our family,” said Noor Mohammad.

The details of Sultan’s journey to Afghanistan are sketchy in Noor’s mind. But what he recalls clearly is his father’s arrival back home with colourful Tangas and tall horses. “My father had told me stories about his arrival,” said Noor Mohammad. “He cherished those memories till his end.”

Afghan Horses

As Sultan entered Nawa Kadal in Srinagar, with his troupe, it caught everyone’s attention instantly. “My father had a huge stable at home. It used to be right there,” recalls Noor Mohammad, pointing towards a line of concrete houses standing next to his modest home.

As the word spread among Srinagar’s elite, just a handful then, Sultan started receiving invitations and offers. “A Tonga was a luxury ride of the rich and affluent during those days,” said Noor Mohammad.

The first two Tangas were sold to Mohammad Jamal, a carpet dealer from down-town and Beigh Sahab from Islamabad town. These sales helped Sultan establish himself among the elites as a Tonga and horse trader. “Within less than a month of my father’s arrival in Srinagar, he had sold all six Tangas and horses,” recalls Noor Mohammad.

The following years saw Sultan take frequent trips to Rawalpindi, one of the key markets feeding landlocked Kashmir then. Once back to Baramulla, the Mahraj Gunj based merchants’ who used to travel with Sultan, would put their purchases in Srinagar bound boats. “Most of the transportation was done via Jhelum River then,” recalls Noor Mohammad. “These goods were then received at different locations along the river in Srinagar city.”

For almost the next two decades Sultan and his family had hegemony over Srinagar’s Tanga and horse trade. “But things started to change after 1947,” said Noor Mohammad.

Death Trap

On October 22, 1947, when tribal raiders from Pakistan crossed over and reached Baramulla, Hindus and Sikhs living in different parts of Kashmir valley, started to migrate towards Jammu, some 400 kilometres away. The fear of war saw huge migration from Baramulla, Srinagar and Anantnag belts. And in order to ferry the terrified lot, all available modes of transportation were used including Tangas.

Noor Mohammad recalls his father talking about the massacre of Tanga drivers at Nagrota, a highway town near Jammu, by Hindu mobs. Out of forty Tanga drivers, who were hired by Hindus and Sikhs for their Jammu bound journey, only two drivers managed to come back alive. They were apparently from South Kashmir.

After the news of Nagrota massacre reached Srinagar, it panicked every transporter in Srinagar including Sultan. Interestingly, the second batch of twenty Tangas from Srinagar, who were on-way to Jammu, turned around from Batote – another highway town, after they heard about the massacre in Nagrota. “Despite the fear, they first shifted their passengers safely in Jammu bound Tangas,” recalls Noor Mohammad.

The events of 1947 permanently shut the Rawalpindi route, forcing traders like Sultan to look for alternatives for survival. For the next few years, till the dust settled, Noor’s father stayed at home, trying to feed his family despite hardships.

Trading In the 1950s

In the late 1950s, disturbed by rising debt and entry of automobiles, Sultan decided to look for an alternative market from where he could get Tangas and horses. After he asked around, he was told that the best Tangas and horses are available across Banihal pass in Punjab.

The closure of Rawalpindi route helped Amritsar and Patiala to evolve as alternatives. “While Patiala was known for making beautiful Tangas, the animal mandi (market) in Amritsar provided horses,” said Noor Mohammad.

Passing On

In 1965, at the age of seventeen, Noor Mohammad took his first trip outside Kashmir with his father. Almost five decades later Noor Mohammad recalls details of that visit vividly. “It was one of the most beautiful journeys of my life,” he said with a smile.

That morning, Noor Mohammad and his father boarded a red coloured bus, originally meant to carry mail between Srinagar and Jammu, with a seating capacity of just eight, with their helpers. There were three such buses between Srinagar and Jammu, all operated by Radha Krishna Transporters.

“They had half portion filled with mails and other half had seats,” recalls Noor Mohammad. Interestingly, these three vehicles had three brothers from Udhampur as drivers. “It took us four days to reach Jammu as they would stop for collection and dispatch of mail almost everywhere,” said Noor Mohammad.

From Jammu, after a night stay at Pathankot, Noor Mohammad and his father’s group stopped in Patiala.

“After placing an order for Tangas, we moved on to Amritsar to buy horses,” said Noor Mohammad.

Once the horses and Tangas were ready, Noor Mohammad and his father started their journey back home. It took them 12 days to reach Srinagar. “It used to be a very dangerous journey. Crossing Banihal pass on Tanga used to take two days at times,” he recalls.

Plummeted Demand

Once in Srinagar, when Sultan and his son approached their potential customers with their latest purchase: 24 horses and eight Tangas, the response was not as it used to be during Rawalpindi days. “Both qualities of Tangas and breed of horses were entirely different now,” said Noor Mohammad. “The horses my father used to get from Afghanistan could easily adapt in Kashmir given similarity in terrain. But horses from Amritsar were good for race only.”

Given the lack of choice, Sultan and his young son managed to convince his rich customers in Srinagar, and their business started to flourish again.

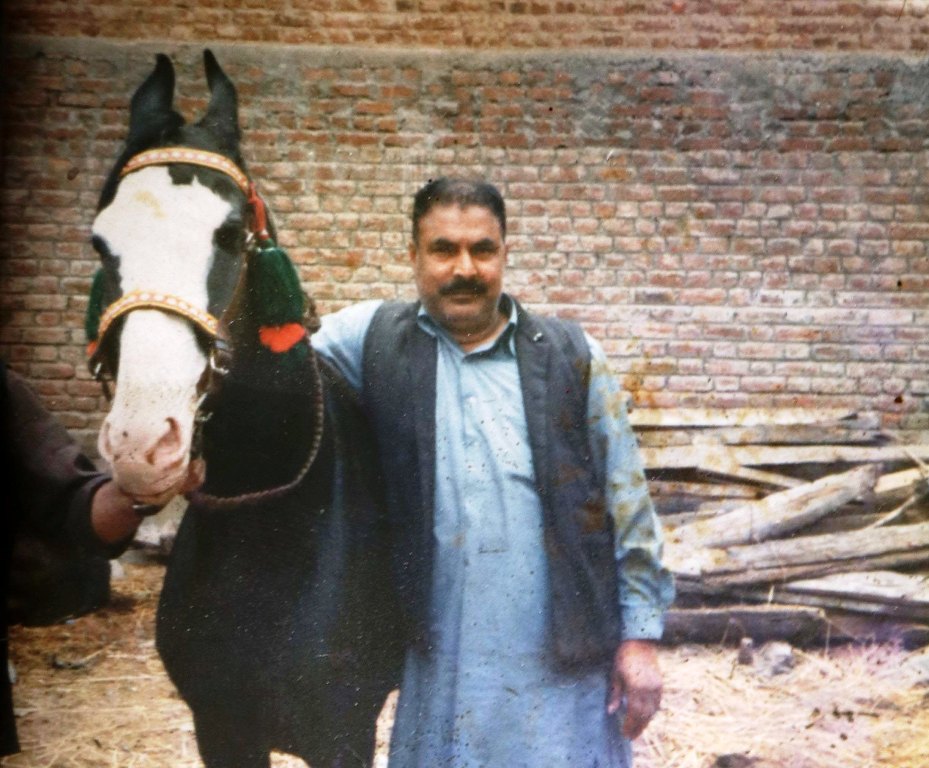

With Noor Mohammad now taking care of his father’s business successfully, Sultan decided to get him married in 1968. “I went to get my bride on a decorated Afghani horse, with a royal lookalike umbrella shielding my head,” said Noor Mohammad with a grin. But more than his own wedding Noor Mohammad recalls weddings of Srinagar elites, where his horses carried grooms through decorated bazaars and bridges, at times spread across kilometres. “A rich carpet owner got Zaina Kadal decorated with flambeau on both sides for his son’s marriage,” recalls Noor Mohammad. “I had never seen such a beautiful wedding since.”

Sultan’s Legacy

The death of Sultan in 1975, coincided with the fall in demand for Tangas and horses, as motorcars started flooding Srinagar roads. “These petrol driven beasts became new favourites of the rich and influential,” said Noor Mohammad sarcastically.

In order to survive the change, all of Sultan’s sons shifted to other trades, except Noor Mohammad.

Being close to his father, Noor Mohammad started riding one of his Tangas between Zaina Kadal and Amira Kadal in Srinagar, ferrying passengers for survival.

“I would also ferry passengers between Srinagar and Baramulla at times,” said Noor Mohammad. “But compared to cars, we were costly and time-consuming.”

But apart from the old Tanga, Sultan had left something else to Noor Mohammad as part of his legacy – his contacts in the Bombay’s film work Bollywood.

Sultan was famous in Bollywood for his collection of top breed horses, which he would provide to visiting shooting crews in Kashmir. This helped Noor Mohammad compensate for his falling income.

For Bollywood

After Sultan’s death, Noor Mohammad was approached by a Bombay based casting director for horses, which were to be used in Amitabh Bachchan starrer Lawaris (1981). “This added income helped me survive during difficult times,” recalls Noor Mohammad. “But it was not regular.”

After that both Noor Mohammad and his horses featured in a number of box-office hit movies including Satte Pe Satta (1982), Betaab (1983), Karma (1986), Palay Khan (1986), Zalzala (1988), etc. “Those were beautiful times. I was young and Kashmir was beautiful,” said Noor Mohammad with a hint of sadness in his voice.

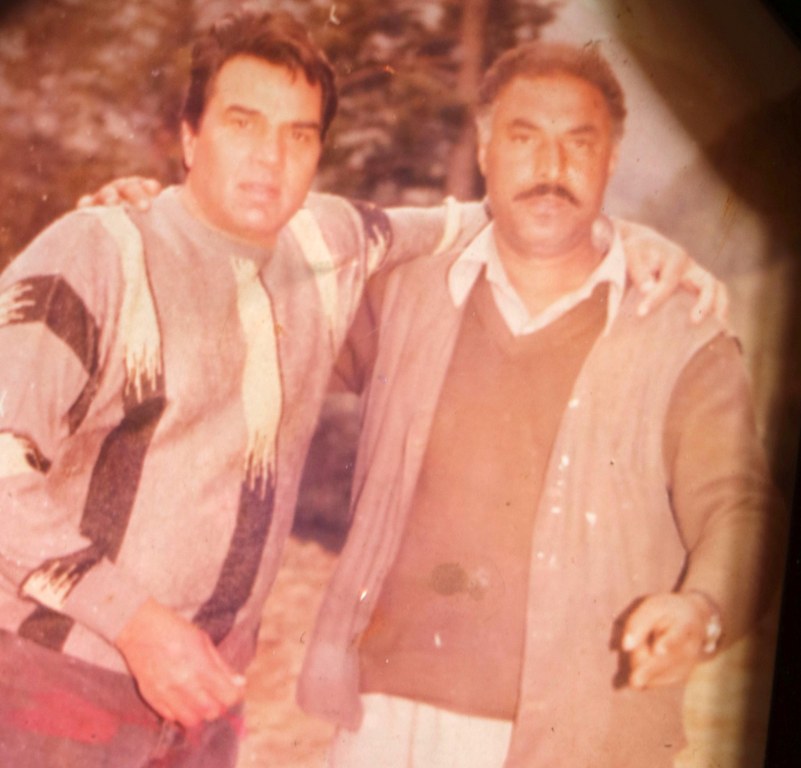

Then suddenly he smiles, as he recalls how crew and cast of Betaab (1983) tracked him down all the way to his house in now congested Nawa Kadal. “The casting director of the film, along with Sunny Deol and Nazir Bakshi came to my house looking for horses for the movie,” said Noor Mohammad with a smile. “They had already transported a few horses from Bombay but Sunny (Deol) was not satisfied.”

Once Noor Mohammad showed Sunny Deol and his friends a particular white horse, which he had brought especially for Budgam’s Agha Yousuf, they couldn’t resist admiring him. “On Nazir (Bakshi) Sahab’s insistence, I ended up selling that horse for Rs 15,000 then,” recalls Noor Mohammad.

That moment seems to have stayed with Noor Mohammad, who now gets nostalgic every time a Bollywood song plays in the distance. “I have worked with all great heroes like Rajinder Kumar, Feroz Khan, Dara Singh, Amitabh Bachchan etc,” he tells with a sense of accomplishment. “But that era is gone forever.”

Son In Car

In the summer of 1989, when the first bullet was fired in Kashmir, Noor Mohammad was with Lucknow based film director Muzaffar Ali shooting for his upcoming mega project Habba Khatoon. “I need not to tell you what followed that first gunshot,” said Noor Mohammad sadly.

In the following years, as militancy intensified, Noor Mohammad’s locality, which once resonated with giggles and sighs at the sight of beautiful Tangas, would witness a killing almost every day. “My family burned all the pictures I had clicked over the years with Bollywood stars,” said Noor Mohammad sadly. “I don’t blame them for destroying my memories. Those were absolute mad times. You never know how people had taken you standing next to Amitabh or Dara Singh?”

With the onset of militancy, Noor Mohammad lost another part of his income as marriages were now celebrated in absolute simple ways. In most of the cases, there was no celebration at all. “The days of using drums, horses, orchestra, lights and umbrellas for a groom were over,” said Noor Mohammad sadly. “There was blood all over Kashmir, how could anyone have celebrated anything.”

Besides, the simplicity adopted in marriages was out of respect for the dead who were killed in combat in downtown, Srinagar. “Even if someone would have asked for orchestra, I would have refused him out of respect for those who died in the neighbourhood,” said Noor Mohammad emotionally. “Every street in this locality is stained with innocent blood.”

However, despite raw emotions, and sense of belonging, Noor Mohammad couldn’t control himself from crying when his only son Bashir got married in 2006. “Unlike family tradition, he went to get his bride in a car as the situation was tense in Srinagar,” said Noor Mohammad with a hint of sadness in his voice. “There were no horses, no lights, no umbrellas etc. He left in the darkness and came back discreetly with his bride.”

With a horseless Tanga still parked in his now shrunken lawn, Noor Mohammad reflects on his father’s legacy and the times he has witnessed. “I sometimes miss the sight of a beautiful Tonga, tic toeing down a cobbled street,” said Noor Mohammad thoughtfully.

But Noor Mohammad knows that these streets have seen a lot more than just cars, since his father’s first Rawalpindi trip.