Come winters and Kashmir’s traditional storytellers would get instantly busy, not in so distant past. In absence of the modern tools of entertainment, storytellers were in demand and the tradition survived generations of occupation and disempowerment. With the tradition literally lost, Shams Irfan meets Khazir M Wani, a legendry dastaangou, to recreate the narrative of a glorious past

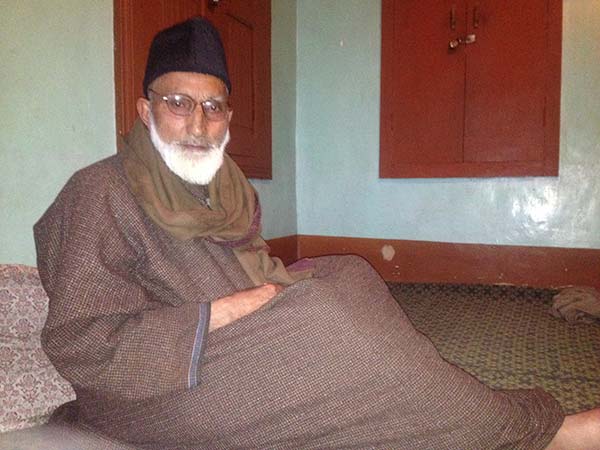

On a chilly winter afternoon, 85-year old Khazir Mohammad Wani, a retired Pampore Municipal Corporation employee, is taking siesta. The sky outside is overcast with neat silver clouds and a prediction of heavy snowfall.

Wani is an extra-ordinary man. His free flowing grey beard, deep sunken eyes, wrinkled temple, pointed nose, angular cheekbones and aristocratic visage, all contrast his life’s story of ‘struggle for survival’.

But Wani has a lot to relish from whatever modest existence he has managed so far. One of the best storytellers in Kashmir for over four decades, Wani would add colour to otherwise dull, lifeless and unnecessarily long winter nights with his artistic narration of Dastaan’s, the long stories, told in prose and poetry.

Then, Dastangou’s (storytellers) used to be the sole source of entertainment for generations lacking access to primitive technologies.

The Journey

Wani’s childhood memory dates back to 1947, a time period that thrust a new political geography on sub-continent including Kashmir. A paying guest in Srinagar’s Alia Kadal area in 1947, for sake of attending school, Wani remembers how the fear of getting killed by Kabailis (tribal raiders) made him quit his studies and rush home.

“I was good at football,” recalls Wani. “I remember playing a friendly match at Eidghah when Kabailis showed up with guns. Next day chaos started ruling.”

Maharaja Hari Singh’s flight from Srinagar to Jammu, in wake of raids, marked end of his family’s oppressive rule. “I was once taken to Awantipora for begaar (forced labourer) as a revenue official was shifting his residence,” recalls Wani. “But what I have heard from my father and grandfather about begaar system, I feel lucky to have been born at the fag-end of Dogra rule.”

Such was the fear of getting killed during those troubled times in 1947 Kashmir that a scared Wani did not visit Srinagar for next three years. Then, Muslims hardly cared about education and systemic discrimination was in vogue. “Even teachers were barely middle pass,” remembers Wani. “In entire Pampore, there were only two Muslims who were government employees.”

Maharaja’s transferred power to Sheikh Abdullah, a popular mass leader. It positively changed Kashmiris, at least for some time!

Taking advantage of that change, Wani was appointed in 1950 as Pampore’s Octroi in-charge on a monthly salary of Rs 23. His job was to charge a tax of “two paisa per item” that tongas bought into Pampore, a job he retained for next 40 years.

Wani remembers the enthusiasm of working for his “nearly independent nation” that Sheikh had instilled among Kashmir’s new Muslim working class. “Before joining my duty, I and my colleagues were taken to civil secretariat and made to swear by Allah and Kashmir that we won’t indulge in corruption,” says Wani. “And I upheld that pledge till I retired.”

Dastaan-e-Gulrez

Wani followed Sufi Islam and was inspired by faith healers and soothsayers from an early age. He has decorated a bare wall of his drawing-room with a black-and-white picture of Lassa Sahab, a Sufi saint from Wuyan, famous for two things: his ultra-sensitive dog Shera and his selfless attitude towards material things.

Wani’s journey as a storyteller had an interesting takeoff in 1950. With a friend, he had gone to Kulgam to sell tobacco. “I had read a couple of story books lately. I had good memory. Rather I still have good memory,” says Wani, flashing his strong white teeth. “After selling tobacco for the day, we needed a place for the night stay. Since we were carrying tobacco with us, staying at a local mosque was out of the question.”

They wandered about in the village before stopping near a big house. With an elderly man sitting on the window, Wani was desperate to get his attention. Out of instinct, Wani began singing a few lines from famous Persian love tragedy Gulrez that he had read recently.

Ashq rawraawna syden ti saadan,

musafir naav bawaan shehzaadan,

Hatooh ashqoh karey dhon deedeney jaaye,

Ghamik zolan kartham tas roveh paay…

A Persian prose by Zai-u-Din Naqshbandi, Wani recited poetic lines from noted Kashmiri poet Maqbool Shah Kralwari’s translation. Kralwari’s translation in early 19th century made Gulrez a household name in Kashmir.

“I had such a clear and powerful voice that it took that elderly person seconds to invite us inside the house,” remembers Wani. “It was a big seven taakh house. (A house with seven set of windows in a row)”

And within no time both Wani and his friend were inside the house.

“Do you know how to read Gulrez,” the house-owner asked while letting Wani in.

“Yes, sir. I do.”

“All of it?” the elderly sought reconfirmation.

“Yes, sir. All of it.”

“I will let you stay at my place if you read Gulrez for us tonight,” said the Kulgam elder before offering the duo tea and bread.

The host sent a word out to his friends and relatives that a Dastangou is staying with him. Instantly, his house turned festive look as entire space of his grand house, third storey hall, filled.

From a local cleric, a copy of Kralwari’s translation of Gulrez was borrowed for Wani. Special dishes of duck eggs, spinach and meat were cooked for the guests. “I felt two things at that time: importance of possessing knowledge and regret of leaving my studies midway,” says Wani.

“That night I read Gulrez as if the story was unfolding in front of me,” Wani remembers. “I was improvising, putting emotions at the right places – sometimes crying, sometimes laughing as I was feeling the longing, pain and love of the Gulrez protagonist.”

That night changed Wani and made him one of the most sought after storyteller in Kashmir, a status he retained for next four decades. The next morning when Wani left, entire locality followed him to the tangha (horse cart) stop.

Bait-Ul-Aman

The years following Wani’s Kulgam sojourn were both intriguing and challenging.

While Wani was brushing his storytelling skills, the necessity to earn decent living for the family, kept him occupied. As the word about his talent and voice spread, Wani would get an invitation for storytelling almost daily. “People would simply listen to my stories in amazement. Being able to read was a luxury that only a few of us had at that time,” says Wani.

Wani owes his instant fame to his ability to improvise his stories according to the taste of his audiences. Dichotomy in Kralwari’s Gulrez version is fascinating: it is interpreted as a story about Ashiq and Mashooq (lover and beloved), and Ishq between Maabood and Abad (God and his creation). Wani had mastered both. “I would simply gauge my audiences taste with first few random lines and then interpret rest of it accordingly,” says Wani. And mostly, it was the romantic interpretation that sold.

But there were a few “learned people” who would request Wani for the deeper meaning of the Gulrez.

Wani recalls one such night when he read Gulrez in a sufi mehfil (gathering) on a floating shikara, under the moon light, in Dal Lake. It was 1962. He was offered Rs 200 for the night by a businessman to explain the meaning of Bait-ul-Aman in Gulrez.

“There was a good gathering of people. Apparently, very decent and educated, they were not Ashiq-Mashooqi loving crowd,” recalls Wani.

After feasting on multi-cuisine Wazwaan, Wani started Gulrez. He would read a few couplets and then stop to explain the verse, sometimes drawing parallels from rich Islamic history, sometimes substantiate his explanations with anecdotes from Prophet’s life. He went on till he reached the point where Zai-u-Din Naqshbandi, talks about Bait-Ul-Aman and which Kralwari retained unchanged in his translation. “Stop,” shouted Wani’s host. “Explain Bait-ul-Aman.” And before Wani could react he added, “But I want an explanation that is unique and apt. I want to know everything that is hidden behind black and white ink-marks.”

“I am just a storyteller. I read what is written by the author. How can I tell you what he really meant?” Wani tried to convince his host.

But Wani’s host knew about his sufi leaning and his association with some of the reverend sufi saints of his times. “I know all about you. I know you read Gulrez for sufi’s and saints. So please tell me about Bait-ul-Aman,” said Wani’s host.

Left with no option Wani began explaining, “Bait-Ul-Aman is a person’s heart. It is the place of Aman i.e. peace. One keeps looking for peace in material things of life when actually it is inside you. Heart is where God resides and if you can find God you will find peace.”

Wani’s explaining ended with a big round of applauses and adulations from the crowd. They looked happy and content. That moment stayed with Wani. He can still hear echoes of those applauses. And remember almost every face that was part of the gathering.

“That day onwards, I became more involved with the deeper meaning of Gulrez. With that I slowly started to confine my visits to private houses,” recalls Wani.

But winters were still dominated by gatherings that would relish Gulrez for its Ashiq-Mashooqi content. “Till late eighties I would spend winter nights at different houses across Kashmir reading Gulrez and other stories.”

But there is one particular winter that Wani wants to remember till he is alive, the 1958 winter when he read Gulrez for 22 nights at a stretch for Lassa Sahab.

Every evening, after completing his days work, Wani would walk to Wuyan, 7 kms from Pampore, and read Gulrez to his saint. “Every verse had to be read twice as he was highly fascinated by its content and deeper meaning,” remembers Wani.

Throughout his career as storyteller Wani had never charged anything for reciting Gulrez. “It was free of cost. Yes, people used to give whatever they liked. But I would never ask for anything ever,” Wani insists.

Apart from private gatherings Wani was a regular at religious and Sufi mehfils (congregations’), or niyazs (supplications) till late 80s. “There I would read Yousuf Zulaikha, the tale of Hazarat Yousuf,” recalls Wani.

Wani retains a rick collection of old dastaan books. “I used to read Jhangnama, Gul Noor, Raina Zeba, Khawarnama and other long stories.”

Introduction of Persian forms of the masnavi and ghazal in Kashmir is the contribution of Mahmud Gami (1765–1855), the celebrated poet from Dooru Shahabad. His poem Yusuf Zulaikha is a major contribution to Kashmiri literature. Comprising 700 verses, it is the first and the most popular masnavi in Kashmiri that was rendered into German by the 19th-century European scholar Fredrich Burkhard.

Wani’s storytelling ended with radio, television, and books becoming common. “All of a sudden people got disinterested in Gulrez and other such stories,” he laments.

Early Life

In 1947, Wani was studying in Bagh-e-Dilawar Khan School in 9th standard. He was a bright student who secured second position in a written examination that 240 students appeared for. “That was top secure scholarship that Maharaja had announced,” Wani remembers. “The topper got a scholarship of Rs 15 a year and I got Rs 10.”

Then, Wani recalls there was one bus leaving Srinagar in the morning and reaching Islamabad in the afternoon. This Kashmir Province Service bus was not meant for transport but to ferry dak, the posts.

His early memories include Pandit revenue officials distorting the entries of Muslimn landholders. They would mention Gulleh, Sulleh, Maamkol, Lassa, Rahet, Fateh, Aziz in revenue records and not Ghul Mohammad, Mohammad Sultan, Mohiuddin, Ghulam Rasool.

Owning land during Maharaja reign was a burden for peasantry as one had to pay 12 anna per trakh as maliyah towards government. “Then all landlords in Kashmir were Hindus because they were close to Maharaja,” Wani remembers.

In Pampore, Wani recalls, almost eighty percent of the cultivable land was divided between two Pandit families – Raghu Mattoo and Nand Mattoo.

Wani remembers how Pohar Chakh village, located on the outskirts of Pampore, came into existence.

This Chakh (land in local parlance) belonged to Raghu Mattoo, grandfather of Amitab Matoo, who was a high ranking officer in Maharajah’s government, almost equivalent to present day Collector. Forefathers of today’s Pohar Chakh resided in Beerwa. They had consumed beef ad were facing an immanent death as punishment when Raghu Mattoo offered them a barter. He shifted them to his Pohru estate which they would till for him in lieu of their life. Post-partition when the Chak system was over, they owned the land they were tilling.

Last Wish

Wani’s memory is sharp. He remembers his times and his glory. He imagines reversing the time. “I wish I could have one such night where I would read Gulrez and other stories,” Wani insists on every single word while looking at the overcast sky outside. “Life was beautiful.”