Line of Control has historically been a cartographic imagination. But the fence that emerged around the divide in the last few years has started impacting the lives of thousands of people living on Kashmir’s periphery, RS Gull reports.

The sun is about to set and Wazir Mohammad is in a hurry. He had left his village to collect items from different shops in Uri town. As it was getting dark, he had to rush to his village located between the zero line of the Line of Control (LoC) and the fence. If he fails to be in time, the soldiers manning the fence will lock the gate and leave, and he will have to wait till dawn to reach his home.

There are thousands of people like Wazir living on the other side of the fence who are the new underdogs of Kashmir society. They carry I-cards distinctly different from the other people living closer to the LoC across the state and sustaining their life differently in presence of a formal barrier that restricts their movement.

Haji Akbar Hussain has lost connection with his in-laws. “I live in Bagal Dara and my in-laws are from Dokri. It would usually be an hour-long trek from my village. But not any more,” Hussain told Kashmir Life. “Both the villages are fenced and now I have to come out of fence and reach Poonch and then take a vehicle to reach another gate of fence at a different place, then go for a long trek and meet them. It is a day-long affair now.”

Last year, Hussain faced the reality of the divide when he chose to attend a marriage of his Dokri relatives taking the traditional mountain trek. “The gate was closed and we had women along with us, besides a good quantity of curd that we usually take to the relatives. For the whole day, the gates remained locked,” he said. “Even after the formalities were made, soldiers did not open the gate because the gatekeeper had left along with the keys. We returned after remaining hungry and waiting for most of the day.”

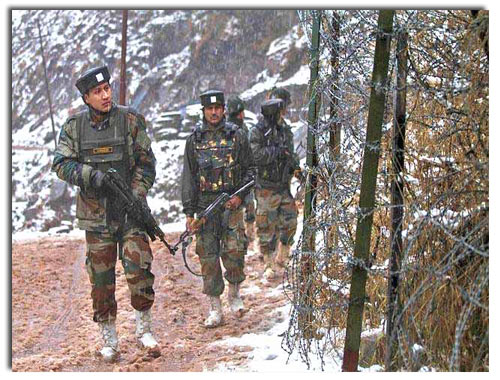

The political border in J&K state, a cartographic creation that only soldiers understood, was invisible to a commoner since the ceasefire line of 1949 to the LoC post-1971. Barring the tensions between India and Pakistan when there were restrictions on movement, the LoC remained porous enough not to prevent the border residents from either side to interact. Prior to militancy, marriages would take place between the clans straddling the LoC with permission from the rival armies. But militancy made LoC a physical structure that is floodlit from dusk to dawn. Anybody flying overhead or around can see the divide.

The 12-feet high fence at LoC was an engineering feat that cost the defence ministry more than Rs 1100 crores initially. A single km requires an aggregate 260-ton cement, iron pickets and steel wire. The fence comprises two parts with an eight-foot gap in the middle which is filled with coils of razor-sharp concertina wire which is charged and can cause electrocution. Sophisticated electronic gadgets, mostly imported thermal imagers and sensors are installed that raise a sound alarm system if any motion is detected.

The work on fence was started in 2003 at the peak of shelling from Pakistani Army. It was believed that Pakistani army was using shelling to help militants infiltrate while literally paralyzing the civilian population living on this side of the LoC, thus creating problems for the government. As fence erection near the LoC resulted in a number of casualties, the defence establishment started fencing at a safe distance that left a vast population between the zero line and the fence.

PDP leader Imtiyaz Ahmad Banday who is also a lawyer says the fence was barely 100 meters from the local tehsil office in the Mandi area. “The entire population were moved out from certain areas like Kerni and temporarily settled far away from the zero line and much farther from their hearths and fields.”

The erection of the fence forced a new routine for the inhabitants on LoC. Localities were sliced and people living on this side had the fields on the other side and vice-versa. Residents moving out of the fence had to report to the gates, get registered and report back within a specified time, get frisked and get in. There were problems for the women who had to undergo frisking by male soldiers for a long time. People having their fields and homes divided by the fence would spend most of the day going and returning. “It was more of the official routine – going at 8 am and returning by 5 pm,” said Ghulam Nabi in Mendhar. “Farms are unlike offices. They require a round the clock commitment.” Khush Dev Maini, a Poonch historian says the district’s 27,000 people in 42 villages are divided by the fence. “People have no social life,” he said, “Fence opens only after the laid down norms are completed and sometimes in emergencies, they do not open at all. That is the mess.” —

The fence has become a major barrier for the people now. “We do feel the difference after the fence came up. The militancy is down and it is obvious,” says Prof Joginder Singh, who runs a trust that provides artificial limbs to the victims of border minefields. Singh extensively visited the fenced areas and saw the impact of the fence, “I went to Swara area in Mendhar and I saw the people living downhill from the fence and for two km, there is no soldier,” he said. “These villagers can be kidnapped overnight and who is responsible for that?”

Ajaz Ahmad Jan, the young National Conference lawmaker who represents Poonch in state legislature said the fence has snapped the roots of militancy in Poonch. “But we need to take care of the people who are stakeholders, now. When India and Pakistan agreed to a ceasefire, it was the major shift in the hostilities that reduced the problems of our citizens. Since there is no shelling going on, it is high time the fence is taken to the zero line and it will have a major positive impact on the situation,” he says.

Jan believes the Army and the civilian population have excellent relations and that is the main reason why there is no reaction to what the fence did to the people. “The soldier is just a call away in grief and happiness. They extend help to people every time. The improved situation helped Army to take back the population of Kerni to their ancestral village. At a few places, the fence was moved closer to the zero line. Army also permitted grazing of herds in a few meadows but most of them are still no-go areas which is hampering the local economy. But the soldier can’t undo the impact of the fence on the society,” asserts Jan. “Vast swathes of land are not being tiled because of the fence and that is a huge loss to the people.”

It is not only the economy that is suffering. Locals say they are severely suffering for social reasons too. “We are in a situation that people do not want to get married with us because of the fence,” says Haji Akbar Hussain, who lives in a hamlet falling in Dagwar Panchayat. “Our women have to report earliest by 5 pm to get home because the lady constable posted for frisking at our gate has to go home.” Adds Banday: “People in the town say that if they can’t be part of the grief and happiness on the other side of the fence (not LoC), there is no fun in such a marriage.”

The defence establishment is doing its best to manage the population at the LoC. Banday, son of a local leader Ghulam Qadir, who was arrested by tribal raiders in 1947, recalls that soon after 1965, the government approved a depopulation policy. “They wanted to relocate the villages living near LoC and get them closer to the town downhill,” Banday said. “But it triggered a backlash and my father spearheaded the campaign, saying that if the residents are being forced to leave their ancestral places, the government is actually paving way for the raiders to do what they want.” The policy was later abandoned.

At the outset, it may appear that the fence might have broken the back of militancy but it can’t devour the social structure and local affinities. Even at the peak of most modern vigil, instances of wives crossing the LoC after brawls with their husbands in Poonch were not so uncommon. There are incidents when the boys and girls cross over and marry on the other side with their relatives and later return back home.

Managing this reality of LoC might not be so easy.