John B Ireland, an American citizen, set out sailing Asia, Africa and Europe for six years between 1861 and 1866. He used to write letters to his mother detailing his impressions of his voyage. He spent late 1853 and early 1854 in Kashmir. Apart from having the firsthand account of the life and the place, he saw French empress’s shawl being woven. However, the most important records are his commentary on the statecraft. Select excerpts from The Wall Street to Kashmir, the compilation of his hurriedly written letters that published in New York in 1859

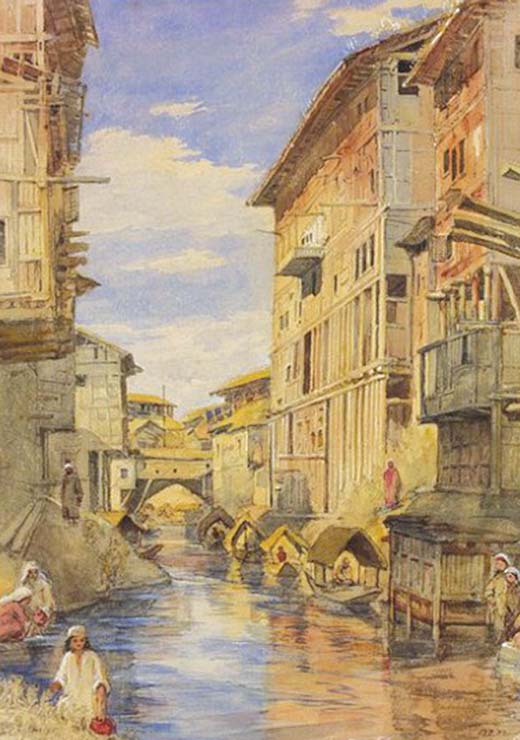

“..The houses generally present a miserable appearance; occasionally the residence of some wealthy man with his extensive zenana (harem), whose apartments are closely latticed, like an immense aviary or state prison; mosques with tall spires or minarets, built of cedar (the deodar)…In the water are boxes for men and women to bathe; for ablutions, if one of their virtues – often the only one.

I then passed the Shaherghur, formerly the residence of the governor, now the treasury of Goolaub Singh. On up the river by the city, I came to an open place, the approach to the country, where were half a dozen small bungalows for the officers who visit this place, and built by Goolaub Singh for their use, perhaps to gain their good-will — no one knows but he, and doubtless an ulterior object to be gained. He is too great a villain to work without some object

…On my way home I met P and C, going to the review (Maharja troops), and joined them. The place was a large open plain near the river, just below the Shahurghur – the old residence of the kings and governors, and now used as such by Goolaub Singh, the present Maharajah (Ghreat King)-a half-fortified palace on the river side.

On the ground we found the troops arrayed on the four sides of a plain of perhaps six acres.. There was cavalry, regular and irregular, foot, and artillery, in every possible shade, color, style, and cut of uniform; some had the skirts of their coats separating behind and closed before, like a frock coat wrong side before.

One fellow had a regular European black frock coat; others, yellow trousers with gold stripes, blue coats, red foraging caps with green band and peak, etc., etc. My memory serveth not to relate all their odd fancies – however, the most of them wore very sensible uniforms (in cut) for the hill work, and with the usual leggings to strengthen the cal^ and straw shoes to prevent slipping on the ice.

In a few moments after we arrived, the Maharajah appeared, in a palanquin, accompanied by his eldest grandson, a chubby little fellow of five or six years, in whom he takes great pride.

P and P both cautioned me not to notice the child particularly, as the natives consider it bad luck, and that you may give the child the “Evil Eye.”

The Maharajah salaamed all of us; I was formally introduced, and we all shook hands with him. After he had gratified his curiosity, asking me all sorts of questions when he found I was neither in the military nor civil service, for he is most suspicious of all strangers, we mounted, he providing us with horses and Sikh saddles… The Maharajah had several beautiful horses for his own use, and had but just mounted, when his grandson refused to go in anything but a crazy-looking English phaeton..

P got in with him, and we followed on horseback, for a turn around the field. On the way we passed a little boy-general, a natural son of the Maharajah’s; then we all dismounted, and sat in chairs, while the troops passed in review before us. The tune of the music was so slow; it was quite ridiculous to see the men balancing on one foot, while they were waiting the note to put down the other.

Some of the men had guns with double bayonets — almost a military Neptune dierre. One had a gun with the barrdeigU fed long I After they had all passed, the Maharajah conversed with us some time, while the grandson took a ride, escorted by irregular cavalry… There must have been about 5000 men on the field. The cavalry wore brass helmets and horse-hair plumes. Besides the regular troops, there was a more useful body – a militia, who were dressed in the ordinary Cashmerian style — a short sack-coat, with loose trousers, and leggings with straw sandals. Then, many mountain howitzers, and a very large style of blunderbuss, to be fired from a “rest”.

The Maharajah was in his ordinary style of dress. He had a loose, red gown and trousers, both of pushmena (the unembroidered material of Cashmere shawls). His gown was lined with flying-squirrel fur. The gown and trousers were very richly embroidered, and worked with gold thread and gold braid. The trousers were tight-fitting, with leggings. His cap of pushmena, lined with fur, and over it a white-and-gold puggery (turban), with a long white handkerchief around his neck.

The eldest son is at Jamoo, one of his fortified resorts on the mountains, on the border of India. The second son was on the field-a small, thin, active man, dressed in scarlet but apparently with little of his father’s ability.

Goolaub Singh is of medium height, stout, and his naturally white hair and beard dyed black, but is fifty, or fifty-five, I am told.

… A month or two since, an officer, in passing through the country, saw in one of the villages, three persons being punished because the donkey of one had broken loose and eaten from a stack of grain, and the other two for taking a little from one of their own stacks before the stack had been assessed.

The first was punished by having his hands tied tightly together over a stick, and then hung on the branch of a tree, the bit of stick resting on the branch; the blood was flowing from his nails. The other two were tied back to back, and each obliged to hold the other on his back for a certain number of hours, and if he allowed the man on his back to touch the ground, he was severely flogged.

The sale of the country by the English to Goolaub Singh, was a most extraordinary piece of mis-government and ill-judged strength. ..

And now he (Gulab Singh) tyrannizes as he pleases, and keeps the people in the most abject poverty, not even allowing them to leave the country. P says about fifty escaped in a body a month ago, by bribing the chowkidar stationed at the Pass.

The country is very fertile, and well watered, and admirable climate for a military sanitarium. It might have been the main avenue for all the commerce of Central Asia, which these high duties now drive away.

…Tomorrow morning we are to breakfast, by invitation, with Mookti-Shah, the great shawl manufacturer of Cashmere, and we expect a right jolly time. Each of our kitmagars has been ordered to take knives, forks, spoons, and napkins, for their

Respective masters, so I presume it will be somewhat of a picnic. .. He received us in a miserable little room, about 14 x 18.

The chogars are made of “pushmena”, which is the groundwork or body of Cashmere shawls. Some of his shawls were very beautiful, especially two of new patterns: one of $300, the other of $325, costing about $540 and $590 in New York, with exchanges, duties, transport, and care thrown into the profit and loss account.

Mookti-Shah then took me to his manufactory, a miserable dirty building, the working department one large room, about sixty by thirty. Here were some forty men and boys of all ages from six up to fifty, arranged in twos and threes, at different looms, each one a loom to himself, for all the most valuable shawls are made in looms, in small pieces according to the pattern, and then sewn together. The pattern is not put in colors and squares like our patterns of worsted work for chair-backs, seats, or slippers, but the directions written. When the patterns are made they are all sewn together.

… It was astonishing to see the dexterity with which the children worked these handlooms, and understood their written directions. Most of the people were at work on a magnificent shawl for the Empress Eugenie of France, a white ground or centre, and it will be the most elegant one he has ever made. He says thirty men have been steadily at work on it for six months, and it will require three more months to finish it. The price, when finished will be about 1,800 rupees or $650, and is such a shawl as would sell for about $4,000 in London or New York.

..I took leave and went through one of the canals, in which there were hundreds of domesticated ducks and geese belonging to the Maharajah, which it would be death to kill…I passed within a hundred yards of Ackbar’s famous grove, and on to the Char-Chunar Island,’ where I landed. Two of the trees are standing; the summer-house is gone, and the water-wheel that supplied the fountains has perished like the rest. I picked up a piece of marble for myself, and some plane-tree balls for romantically disposed friends.

..Tomorrow I shall have to assert the dignity of the Maharajah and myself, by pulling the cutwal’s beard, and giving him a drubbing — for pardoning insolence is never appreciated here, but looked upon as meanness or cowardice, though the man may escape a flogging by it.”