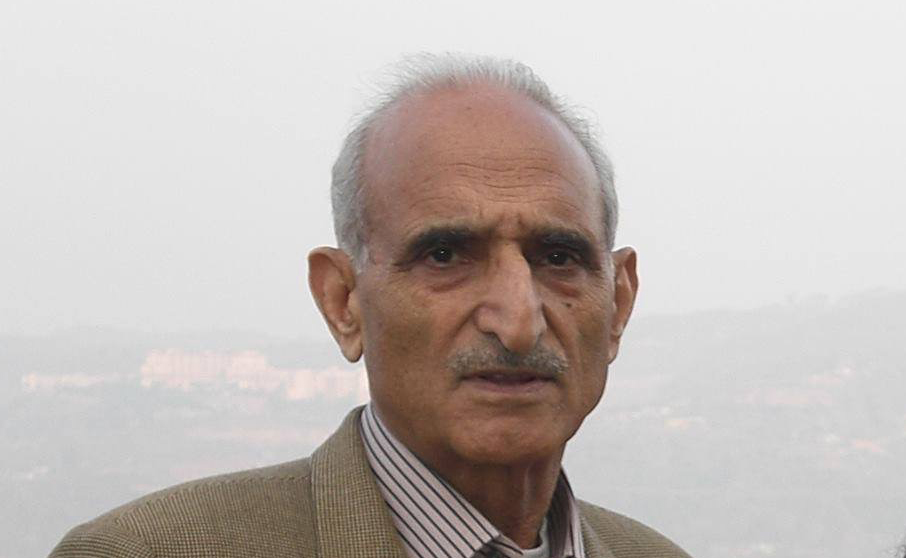

by Mohammad Sayeed Malik

All of us benefited and gained professional skills. More, a purposeful bonhomie became its by-product. The cordial atmosphere within the profession was perceptible, notwithstanding the usual competitive professional rivalries.

Thank God. We, the oldies in journalism in Kashmir, were able to create our first ever Kashmir Press Club (KPC) half a century ago, run it as a vibrant institution for nearly a decade before letting it sign off on its own. It had remained defunct for some time for various reasons.

But, mercifully, it is quiet disappearance contrasted with the rumbustious forced exit of its 5-decade later successor that was also marred by ugly washing of dirty linen in public.

Its almost unnoticed exit, however, cannot overshadow a few significant achievements to its credit.

Public life in Kashmir being perpetually subservient to notorious vagaries of fluctuating political atmosphere, the KPC faded out in the mid-1970s in the wake of drastic change in the political climate in 1975. The event did not even register itself.

The KPC was housed in the only structure that then existed in the Sher e Kashmir Municipal Park and, eventually, was handed back to its owner, the then Srinagar Municipal Committee (SMC), as smoothly as it had been taken over a decade or so earlier

Khawaja Sanaullah Bhat, editor Aftab, was formally elected its first president and re-elected subsequently. Among its vice presidents were Ghulam Rasool Arif of daily Hamdard and Mohammad Yousuf Qadri of the daily Khidmat. JN Sathu became its first general secretary and I succeeded him in the following election.

KPC had been conceived of as sort of an umbrella organization of our individual professional units, like working journalists (news reporters) affiliated to Indian Federation of Working Journalists (IFWJ) and National Union of Journalists (NUJ), Kashmir Editors Conference, non-working journalists, like calligraphists and others directly associated with this occupation.

The primary motivation was to seek solutions to common professional problems and, importantly, to tackle hurdles in the working relationship between the media and the government. Easier said than done, even in those relatively less complicated circumstances

Productively, KPC arranged and regularly held within its office premises a number of events ranging from internal meetings to discuss our professional issues to inviting visiting and local dignitaries from politics and other walks of life and to stage a series of press conferences with local and visiting persons.

All of us benefited and gained professional skills. More, a purposeful bonhomie became its by-product. The cordial atmosphere within the profession was perceptible, notwithstanding the usual competitive professional rivalries.

Not that there were no differences, personal and/or otherwise. As a few chose to go it alone or keep away, for their own reasons. But this was hardly audible, much less so jarringly visible as it is today.

The KPC gained in its public stature and retained its public utility as well as professional credibility until it lasted.

I can recall that on one occasion during Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s (while in opposition) brief presence in Kashmir, we invited him to the KPC office for a free, frank exchange of views. He was forthcoming even on delicate nuances of his political philosophy and many of us came back with a better understanding of what he stood for and why.

He graciously reciprocated our invite a couple of weeks later by hosting a sumptuous lunch on a houseboat in Nagin Lake where some of us also switched into a swimsuit, including veteran Pran Nath Jalali, and joined Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah as he took the plunge into the lake. I remember, how he pulled the leg of non-swimmers and shared jokes with us all. The lunch served was sumptuous.

Another notable KPC invitee—from outside the state—was the then fiery head of the CPI, Sripat Amrit (SA) Dange. It was a pleasure to interact with someone who was highly respected across the board for his knowledge, understanding and repartee. We, reporters, benefited a lot from this kind of productive interaction. Dange’s discourse covered the entire gamut of Indian politics of which not many of us were even aware. Especially, his exposition of certain key nuances of National politics versus Kashmir politics still holds good. For us, it was a useful lesson.

KPC also met regularly to discuss common professional issues and those pertaining to our working conditions. Modern Technology was then nowhere in sight of getting hold of the profession as it stands today. Man still mattered more than the machine and inter-personal relationships were valued for mutual good. Means of communication were still primitive but the credibility of the media and media persons was by and large intact

However, sometime after February 1975, the political climate across the state changed beyond recognition. Sheikh Saheb was back in power. Ironically, the legitimacy of the system returned with a jarring authoritarian streak that adversely affected press freedom. There was nothing in the air to propel the idea of reviving the dormant KPC. Meanwhile, the general atmosphere got vitiated with the new regime seeking to tighten curbs on public opinion and its formal outlet

After winning the 1977 Assembly elections, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah government opted for (a permanent) Public Safety Act to replace the Preventive Detention Act (PDA) that had to be annually extended with legislative approval. Draft PSA had ridiculously stringent anti-media and anti-media-person proviso.

Thanks to our latent, but mercifully not dead KPC-spirit, we all joined ranks and put up strong, fairly long resistance against the PSA. Our persistent protest found echo across the nation. We joined hands and held protest demonstrations. At times we were lathi-charged. There was a hue and cry outside the state. A delegation of senior editors headed by Kuldip Nayar came to demonstrate solidarity with us and joined our protest at Partap Park.

Ultimately, the state government had to water down anti-media and other more draconian provisions before adopting the PSA. Retrospectively, I see it as the victory of our old KPC fighting spirit, though KPC itself was long gone.

Meanwhile, as the KPC remained dormant for long its only building was taken back by the SMC, removing the last trace of an umbrella organization of media persons in Kashmir.

Are we now watching its action replay? Or is it a different thing in its colour and complexion?

(Author is a senior journalist and former editor of Business and Political Observer. This write-up was reproduced from the author’s Facebook wall.)