At 11, poverty forced him to flee home and a theft landed him in Lahore. Since then more than sixty years eclipsed. As the oldest bachelor somehow returned home at 71, he is fighting a battle against going to a place where he lived on alms with arthritis, reports Javid Sofi

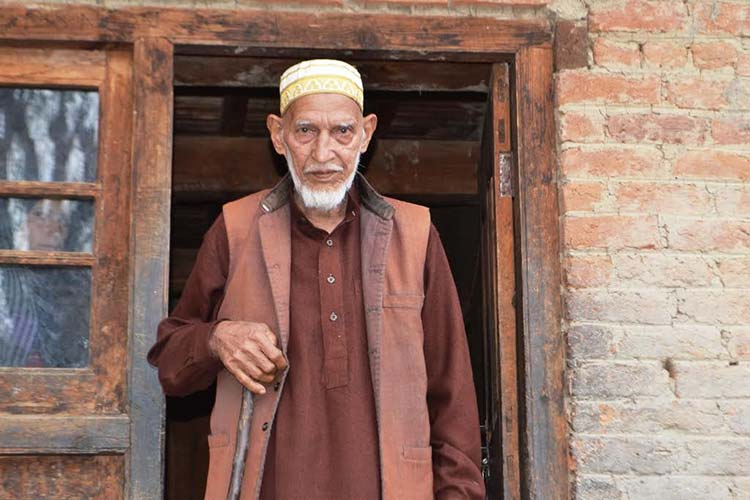

When a stranger knocks at Najar House door, an old fashioned two storied building in Pulwama’s Abhama village, aged Abdul Salam Najar, a Kashmiri born Pakistani citizen, turns pale. He starts quivering actually. At every knock, he feels ‘they’ have “come for me” to “push me away”.

Salam, who re-united with his family after sixty years of living in solitarily in Lahore, mistakes the knock as a call from government for his eviction.

Sensing it as an imminent threat, he looks desperately towards his family members, nephews and nieces. Immediately, they produce his travel documents: a passport, a visa and a bunch of applications. Najars routinely suspect strangers as CID (state police intelligence officials) or people from other government agencies, who have left stringent warnings to send septuagenarian Salam to Pakistan. He is overstaying in Kashmir.

“We beg to let him stay,” the family members plead.

Salam’s story starts when he was just 11-years-old and landed in Pakistan somewhere in 1957. Kashmir at that time was struggling with low productivity and mass poverty, triggered by early snowfall in September in the preceding year. The standing paddy crops were damaged. It had led to a famine and the people still remember the miseries they survived with.

Political situation was also not very well. It was Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad ruling over Kashmir. The joint family set up was the most common.

“The government provided five kilograms of wheat grains as monthly ration per family which was too small to last for a full month,” remembers Salam. Villagers, who had no rice to cook, were forced to eat waath, boiled half-cut maize.

In order to make a living and earn some livelihood, a large population from the peasantry used to travel to cities like Amritsar and Lahore in search of labour. Then, seasonal labour was a norm during winters. Farmers after the harvest would travel to Punjab for managing its rice harvest. Most of them would work in the huge rice mills till the onset of winter.

Compelled by the pathetic hunger at home, Salam left for Jammu along with four other villagers, all his neighbours. Interestingly, Abhama, a small village has not changed much since. It still lives a modest life. Residents still travel out to different areas of Kashmir for making their two ends meet.

However, Salam didn’t confide his plan to any of his family members that was an extended family comprising Khalil Mohammad Najar, elder brothers, Mohammad Subhaan Najar and Abdul Gani Najar and sisters, Zoona and Jana Begum. His mother had died when he was a crawling baby of two years of age.

After he fled, it was a neighbour who broke the news to Najars’. Then, residents of this hamlet were hired by contractors to work in Pathankote area where a canal was being laid out.

They had worked on the canal for two months but misfortune shadowed them, there, too. Abdul Razaq, their headman in the group, also a Kashmiri, duped them by running away with their wages. At home, they toiled hard in their fields and then there was snow. In Punjab, they worked hard for two months and the leader turned a thief. Those were tragic times.

Soon, the minor was hunting for another job. They moved to Amritsar, deeper into Punjab. Unlucky, they found no work. Then, many Kashmiri were crossing Wagah border into Pakistan which tempted Salam’s group to go along. Those days, it was common to move between the two countries without passport and visa.

Finally, Salam and his colleagues landed in Lahore. There, they came in contact with a noble Kashmiri fellow, Abdullah, who had established himself as a respectable person. He arranged their initial stay and soon Salam found labour. He started living from hand to mouth in a rented room at Hanif Park in Lahore’s Badamibagh.

Once settled in a room, Salam, with the help of an aide, started writing to his family in Kashmir. Najar’s were happy that their ward was finally traced. They had survived the harsh days with empty bellies. They insisted him to return.

Three months latter Khalil, who was eagerly waiting for his son, passed away. Further stay in Lahore was futile. Salam started return journey. He wished to reach home as soon as possible to grieve for the loss with his family.

But, finally he stayed put. Reason: A Kashmiri police officers Qadir Ganderbali had created a fear among people returning from Pakistan. Tales of his brutality had reached the small Kashmiri community that was living in Lahore. “I was too terrified to return,” recalls Salam.

Writing letters to family stopped after his aide moved to a different place. His fellow villagers had left without informing him. This was the time when India and Pakistan sealed borders between them after 1971 war. Now Salam was formally stuck between two hostile neighbours.

It was during those days of high tension that bad news started pouring in from home. First Gani then Subhaan, his elder brothers, passed away. Gani died bachelor. Subhaan died after raising a family. But the good news was that his sisters had been married off and they were living happily with their husbands.

It was during those days of high tension that bad news started pouring in from home. First Gani then Subhaan, his elder brothers, passed away. Gani died bachelor. Subhaan died after raising a family. But the good news was that his sisters had been married off and they were living happily with their husbands.

Again, Salam started return journey. This time authorities stopped him at Wagah border. “Indian government stopped me from returning home,” recalls Salam. “They demanded visa and passport.”

Salam was back to his Lahore room. He remembers requesting a number of people to help him in getting a passport and visa but none assisted. Due to his abject poverty, the man squeezed in a small room, couldn’t find a match. He lived a bachelor.

Days went on, months turned into years. Salam grew old, his health deteriorated after he was struck with arthritis. Unable to do any work, he survived on charity of some good neighbours. They arranged his meals and medicine.

When neighbours shifted to other place, life became miserable for the old Salam. There was no one to look after him.

But the tunnels do end. One day Sanaullah Dar, a resident of Sangerwani, a neighbouring village of Abhama, met Salam in Lahore. He was moved at his plight.

Sanaullah, whose brother Mohammad Abdullah Dar is living in Lahore, informed him that government has opened Muzaffarabad – Uri road and that he could visit home on valid travel documents.

When Sanaullah returned Kashmir, he went straight to Abhama. He informed Ghulam Nabi Najar, Subhaan’s son about his uncle’s plight in Lahore. Nabi, who was born after Salam’s migration to Pakistan, was told by his father that his uncle lives in Pakistan.

Nabi contacted Abdullah and requested him to assist his uncle in applying for passport and visa.

Finally, Salam applied in India embassy in Islamabad and returned home on August 17, 2015 through Jhelum Valley Road.

“We had never seen each other before still I recognized him on the first sight, his face resembles that of my father,” Nabi said.

Salam, who could hardly walk and needs a support to stand, is looked after by Nabi and his children tirelessly.

His 28 day visa expired. Then, the government agencies wanted him to leave. State police intelligence had asked the local police in July of 2016 to take legal action against him. The instruction reads “the said Pakistani national is overstaying beyond the authorized period of stay in valley, as such, you are requested to take appropriate legal action against the said Pakistani national under intimation to this office.”

“I don’t want to go back, I belong to Kashmir and I wish to die here,” a shivering Salam said.

To comfort his ailing uncle, Nabi had moved series of applications before authorities to stay the eviction order.

Nabi, pleading that his uncle has ancestral property in Kashmir, that he is ill and has no one to look after him in Pakistan, moved an application before commissioner home department for staying the eviction order.

He was assured by authorities that they would consider his plea on humanitarian basis. The file is pending in the home department and the threat persists.

Till that one-liner reaches Abhama, Najars will never have sound sleep.