France’s ‘botanical romantic’ Victor Vincelas Jacquemont (1801-1832) spent 1831 summer in Kashmir at the peak of exploitative Sikh misrule. Letters, he sent home from Srinagar, offer the idea of darkness in which Kashmir merely survived

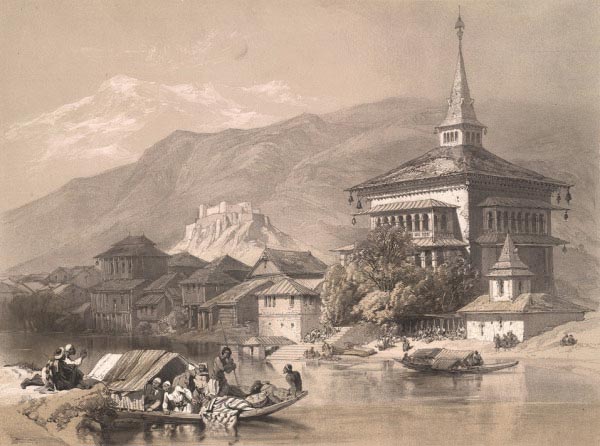

(Painting of life in Srinagar with Shah-e-Hamdan shrine in background by James Duffield Harding in 1847.)

Jacquemont was fairly young when he got extra-ordinary attention in France. He visited America exploring his interests and created a large volume of letters detailing the life and times. Funded by the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Jacquemont spent three and a half years in India, including a summer in Kashmir where he reached with the help of villagers who were forcibly imprisoned to carry his luggage. He wrote a score odd letters from Kashmir detailing the life and politics. While his 80 volume scientific exploration is vital for botany, the few letters he wrote from Cashmere are of key interest to Kashmir.

He considered Ranjit Singh, the single-eyed King who remotely ruled Kashmir from Lahore, and Gulab Singh, then Raja of Jammu, his friends. Ranjit, in fact, had offered him the job of Kashmir governor, an offer he refused. “I sometimes think,” he wrote later, “of the two lakhs a year offered me by Ranjit If I would do the ‘bandobast’ in Kashmir ….From less capricious king, and one who kept accounts better, I should have accepted them joyfully, for it would have been a magnificent opportunity for doing endless good, while at the same time making my fortune by putting aside half a lakh every year. I have never seen any other country in which power was any temptation to me; probably because it was the only one in which I have seen a chance of doing an enormous amount of good to a large number of men in a very short time.”

On March 16, 1831 when he met Ranjit Singh and felt him annoyed “at not being able to drink like a fish without getting drunk, or eat like an elephant without choking”. Terming him malade imaginaire, Jacquemont found “a large band of the loveliest girls of Kashmir” in his palace.

In his letters, Jacquemont has remained highly critical of earlier explorer William M Moorcroft who spent a lot of time in Kashmir in 1814 when Kashmir was under the ruthless Afghans. “Moorcroft did not set a like example of European continence here,” he wrote on August 19 while projecting himself a hermit whose virtue is the subject of universal admiration. “His principal occupation was making love, and if his friends are surprised that his travels were so unproductive, they may ascribe it to this cause”.

On October 28, 1831 he sounds pretty narcissist in praising himself for doing the undoable – for returning from Kashmir without any danger. “…I have just done (that) only one man has attempted before, M Moorcroft; and he never came back – some say as the result of fever, other of poison. But I learnt for certain in cashmere that he died miserably of sabre and gunshot wounds, together with one of his companions”.

His happiness was cut short. Jacquemont died of cholera in Bombay on December 7, 1832. His body was exhumed in 1881 and buried in a crypt near the Gallery of the Zoology Museum of Natural History in Paris.

Here are excerpts from his letters:

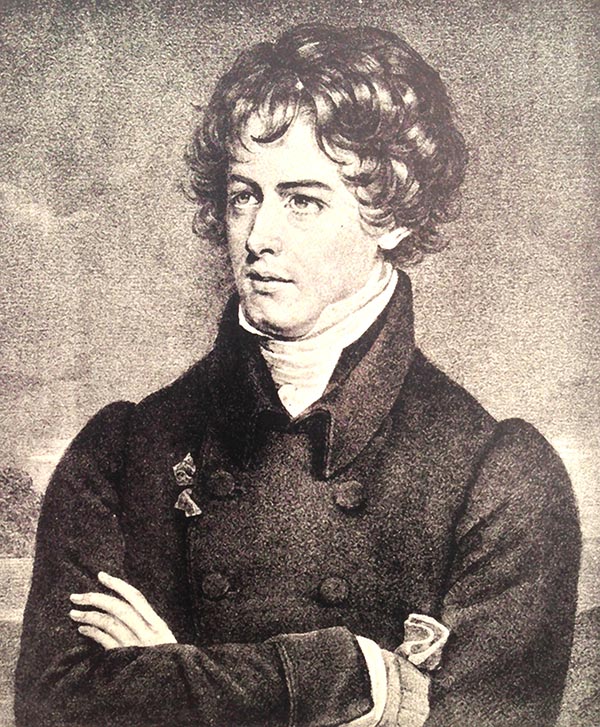

(Victor Vincelas Jacquemont (1801-1832))

KOTLI, on the road to Cashmere: April 23, 1931

…On the road side, I saw the body of a man hanging to a tree, apparently executed that morning. I asked who he was, and why he had been hanged, but all the passengers seemed so indifferent to the spectacle that no one knew more about it than myself. A poor man’s life is considered of but trifling importance in the East!

CASHMERE: May 15

Here I am at last, and have been several days… I arrived here on the 9th. The governor, being informed of my approach, sent his boat and officers to receive me, two leagues from the city, and conduct me to the garden prepared for my residence. It is planted with lilacs and rose trees, not yet in flower, and immense planes. On one of the angles stands a little pavilion, looking over the lake: I am settled in it. My attendants are at hand, in my tents, pitched under the large trees. They are building barracks in haste for my cavalry and horses.

If the governor of Cashmere had been a great lord, I should not have hesitated to pay him the first visit. But he is a man of low extraction, who only holds the office temporarily; and I refused to pay him this deference. For a parvenu he has a reasonably good disposition. It was agreed, at once, that our interview should take place the next day, at Shalibag (Shalimar), the Trianon of the former Mogul emperors. It is a little palace, now abandoned, but still charming by its situation and magnificent groves. It is two leagues from my abode, on the other side of the lake. The governor sent his barge, with a numerous guard, which made quite a flotilla, and I went to Shalibag on board my flag ship. The governor had ordered a fete to receive me.

The fountains were playing in the gardens, which were crowded; the Sikh troops, in their magnificent and picturesque costume, occupied every avenue. Dancing and music only waited for my presence to commence. The governor rubbed his long beard on my left shoulder, whilst I rubbed mine on his right. We sat close to each other on chairs; the vice-regal court sat round us, on the carpet; and, after exchanging the commonplace compliments, the party commenced.

This insipid interlude of songs and dancing, which the Orientals can witness with pleasure from morning till night, is called nautch. It is graceful nowhere but at Delhi. The Cashmerian beauties had nothing in their eyes to compensate for the monotony of their dancing and singing. They were browner, that is to say blacker, than the choruses and corps de ballet of Lahore, Umbritsir, Lodheeana, and Delhi. I remained as long as I was pleased with looking at the fantastic architecture of the palace, the variety and splendour of the groups of warlike figures crowding around, the colossal size of the trees, the greensward, the waterfalls, and in the distance the bluish mountains, and their white summits. After half an hour’s stay, I took leave of the viceroy, and returned home in the same order in which I had set out.

My pavilion has but very flimsy walls: it was closed only by Venetian blinds, elegantly carved, with infinite art. It was open to every wind, and to the inquiring looks of the Cashmerian idlers, who came by thousands, in their little boats, to look at me, as they would at a wild beast through the bars of his cage. I have had it hung inside with curtains, which shelter me tolerably from the wind, and completely enclose me from public curiosity. The governor has sent me a numerous guard of a half regular corps, under his more especial command. There are sentinels all round the garden, and the indiscreet persons who approach it come in for their share of blows. I was obliged to give orders to this effect: I should not be respected without it.

… I mentioned to you a man hanged at Kotli. There were a dozen suspended on trees near my camp, on the banks of the river. When the governor visited me, he told me, with a very careless air, that in the first year of his government he had hanged two hundred, but that now, one here and there was sufficient to keep the country in order. Now mark that the country is a miserable and almost desert province. For my part, if I had to govern it, I should begin by putting in irons the governor and his three hundred soldiers, who are robbers par excellence, and I would make them work in the formation of a good road. They now live lazily on the labour of the poor peasants: they would continue to subsist on the same rice, but then they would earn it.

… As for the pundits, who are all of the Brahmin caste, their ignorance is extreme; there is not one of my Hindoo servants who does not think himself of a superior caste to them. They eat everything but beef, and drink arrack. In India, none but the most infamous castes do so.

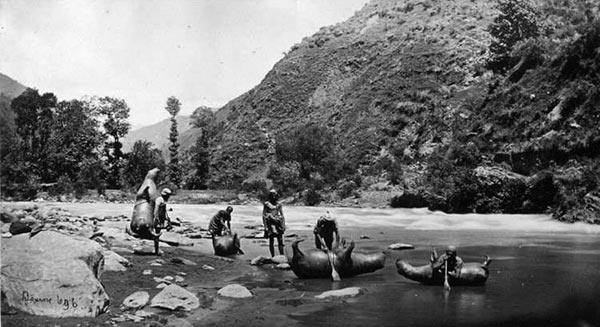

(In absence of bridges, Kashmiris for centuries used inflated animal skin to cross rivers.)

CASHMERE: May 14

… It is possible I may see Mr Allard again in the mountains. The mother of a brood of little mountain rajahs has just died, leaving nine lacs of rupees (two million two hundred and fifty thousand francs). Her children are fighting about the inheritance; and Runjeet has just sent Mr Allard to the spot to remove all cause of dispute – that is to say, the nine lacs.

The day I arrived here, the 8th, the governor sent me as a nuzzer, ten sheep, forty fowls, two hundred eggs, several sacks of barley, rice, flour, sugar, some native brandy distilled from the wine which they make, and which resembles a mixture of bad anisette and bad kirschen-wasser. All this I distributed to my suite; but the king has just sent a new order that my table is to be constantly provided at his expense..

Be it known to you that I have never seen any where such hideous witches as in Cashmere. The female race is remarkably ugly. I speak of women of the common ranks, those one sees in the streets and fields; since those of a more elevated station pass all their lives shut up, and are never seen.

It is true that all little girls who promise to turn out pretty, are sold at eight years of age, and carried off into the Punjab and India. Their parents sell them at from twenty to three hundred francs — most commonly fifty or sixty. All female servants in the Punjab are slaves; and, in spite of the exertions of the English to abolish the custom, it nevertheless prevails also in the north of India.

The Cashmerian politicians whisper that I have come to spy out the state of the country, and its resources, and to treat with Runjeet Sing concerning its cession to the English government. Others assert that I am come with the design of farming it from Runjeet, as viceroy, for so much a year which I shall engage to give the Maharajah. You may guess that I weigh all my words in order to furnish no cause for all these silly reports: I stick to my ilam, my science.

CASHMERE: May 20

… The king, besides, enjoins me to make myself at home in Cashmere. “That country is yours,” he writes, “establish, yourself in whichever of my gardens pleases you best; order, and you shall be obeyed.” I leave you, in order to take a boating excursion on the lake and the river. I have the state boat of the late magnificent governor, and thirty rowers, in my monthly pay. Guess the monthly pay of a rower — two francs forty-six centimes; so I shall have to give thirty rupees a month to these thirty men; but as my situation compels me to be grand, I give them forty, and presents likewise whenever I get out of the boat. What charms me is, that I am drilling two men who promise a good deal for my zoological preparations: the one is a hunter by profession, the other is an embroiderer, with slim fingers. I will make them a bridge of gold, to decide them to follow me into India, where I have yet found no one, even of the lowest class, who would do this business, even for gold.

(For most of the medieval Kashmir, especially between Afghan and Dogra rule, women were completely dis-empowered.)

CASHMERE, May 16

…The governor sent me, on the day of my arrival, a company of Sikh infantry, which is on duty near my Excellency. Two of the horsemen of my escort superintend all the details; and a gentleman of my chamber, at six rupees a month, stands all day at my door, and shows six rupees worth of discernment in his selection of the applicants of all kinds whom he admits.

… It is the custom in the East, that no one can approach a man of higher rank than himself, without paying both master and men. The English in

India discourage this practice as much as possible; but in Cashmere, where the European conventions which we term honour and probity, have not yet penetrated, if I were to punish my chamberlain for receiving a revenue from his key, Cashmerian public opinion would stigmatise me as an unjust and capricious lord.

… the governor of Cashmere came yesterday to pay me a visit at my own house. He has all the look of a fool; but he possesses the very rare virtue in this country, of obedience to his sovereign, and executes punctually all the kind orders of the king in my favour.

… The country is now so completely ruined that the poor Cashmerians seem to be in despair, and are become the most indolent of men. If one must starve, it is better to do it at one’s ease, than bent under the weight of labour. In Cashmere, there is scarcely more chance of getting a supper for him who tills, spins or rows all day, than for him who, being rendered desperate, sleeps all day under the shade of a plane-tree. A few thousand stupid and brutal Sikhs, with swords at their sides, or pistols in their belts, drive this ingenious and numerous, but timid people, like a flock of sheep.

CASHMERE, May 26

…The governor has given up to me the boat belonging to the late viceroy- thirty men are requisite to work it; add to this, twenty porters to carry the most necessary part of my baggage, in my excursions on dry land, across the mountains; fifteen servants besides, amounting to not much less than eighty in all, making a heavy expense, obliged, as I am, to pay magnificently, that is to say, double or treble the value of things.

.. India is no longer the poorest country in the world to me: Cashmere surpasses all imaginable poverty….

CASHMERE, June 11

… Not but I sometimes perceive the little snares that he (Ranjeet) lays for me. Not long ago, the Governor sent me his secretary to say that he had just received a most mortifying letter from the king. Runjeet stated in this letter that I had written to him that he (the Governor) was a fool, — that nothing went on right in Cashmere, — that he surrounded himself with a set of asses, and left clever people unemployed. He commanded him to ask me who the clever people were, and to employ all those whom I might indicate. I told the Governor the truth: that I had never written anything of the kind to the Maharajah; and that the latter no doubt wanted to laugh at him, and stimulate his zeal by giving him the alarm.

The poor devil of a Governor insisted on my immediately becoming grand elector of Cashmere. He humbly allowed that he was no better than a fool, a very true confession. He offered to make a clear house of it, he particularly insisted on obtaining a certificate of my satisfaction; for he seemed persuaded that I had complained of him to the Maharajah;… I refused the desired certificate; but promised to continue informing the king that I was satisfied with the Governor, so long as the latter should continue to afford me the same motives for satisfaction.

…. The summer here is very hot. But the Governor sends me ice every morning; and I have taught my khansama how to make very light iced punch. I finish my dessert with it; and you will allow that in a barbarous country it is no slight luxury. But I have more lace than shirts. I shall have sixty-eight servants in my pay, which will procure the rajah’s rupees a very rapid expenditure. They bring me every morning a sheep, a dozen fowls, a basket of eggs, a sack of rice and flour, and all other things in proportion ; and I have not a bit of bread to eat!

VERNAGUE; July 1

… Thus, on my arrival in Cashmere, I taught two Cashmerian servants to help me in my zoological preparations. They gained more at it in a month than they would otherwise have done in a year; and yet they have left me. One of them was a hunter; when the people saw him killing all sorts of animals, they rose upon him, beat him, and broke his gun. I had thirty of the mutineers bastinadoed, and threatened with a more severe punishment in case of a relapse. My man was not beaten again, but he became the object of general contempt and hatred, and he told me one day that he could no longer follow a craft which made him so odious. The other also resigned. I can find none to take their places. In these barbarous countries, religion meddles with everything, and raises a crowd of obstacles in the way of the curiosity and ardour of a European traveller, such as you have no conception of.

… Whilst I was going about the highest mountains in this country, a month ago, the two sects of Mussulmauns, confounded in a very unequal proportion in Cashmere, were quarreling about their religion. The Sikh guard sent to restore order, set fire to the city, and disturbed the water in order to fish in it. The two parties fought, killed, and burnt each other for twenty-four hours. It was fortunate that I had left a strong guard at home, for the plunderers came, but were received sword in hand and repulsed.

…A crowd of poor and diseased people gather round my tent, like a gayer one round our theaters. Unfortunately nearly all are incurable: there is blindness of all descriptions, and a host of wretches worn down with most dreadful diseases, which they owe to us.

… The cholera is not unknown in Cashmere. It has appeared twice since the Sikh conquest, and the Cashmerians do not fail to attribute its importation to their new masters.

In the Lake of CASHMERE; August 8

This overpowering heat is rare in Cashmere: they only come when the periodical summer rains entirely fail, which has happened this year. The rivers, from which the country derives its subsistence, have been dry for a month past. This is a public calamity. The people wanted the Mullah’s to pray in the mosques for rain, but the sky was so unpromising that the Mullah’s expecting but little success from their supplications, caused the Sikh governor, for a long time to forbid that the prayers should be offered up.

Yesterday, seeing some stormy clouds about the peak of the mountains, they got the interdict removed which they had themselves called for. The inhabitants of the country hastened from all parts, to a village which I can see from this place, and where they preserve a hair of Mohammed’s beard. If there really be such a thing as faith, or true piety, in the world, it is amongst the Mussulmauns; but the poor wretches will not reap a grain of rice.

The dervishes, who are the least devout of the faithful, should have come to me and consulted my barometer as to the probability of change of weather, before they asked it of heaven. The threatening clouds of yesterday dispersed during the night, as I had foreseen and with a sort of Christian folly foretold. The hot weather has returned to the set fair of the infernal regions.

(A late 19th century photograph showing men and women villagers harrowing the field.)

KAMRAJ, on the banks of Pohru; September 6

(Dispatched from Sopur September 10)

… While I was there (Wullar lake), dissecting large birds, beasts, and fishes, I was informed of the arrival in my camp of a vakil or messenger from the king of Little Tibet, and of a neighbouring mountain chief, at open war with the governor of Cashmere. The former I was told brought my lordship presents from the king, his master. The other came only to pay his respects; he had two hundred of his mountaineers with him, which much displeased me.

Nevertheless, I put a good face upon the matter, and commanded them to wait at a distance, until I was ready to grant an audience to the vizier of Tibet, and the Cashmerian chief. Having resumed my European dress, and majestically seated myself in my chair, under a sort of canopy hastily set up, mats were stretched on the ground, and near me a privileged carpet. My people formed a line on each side, most of them so ragged that you never saw the like in the streets of Paris and when I was satisfied with the arrangement of my court, the Mussulmaun officer of my court went in quest of the vizier.

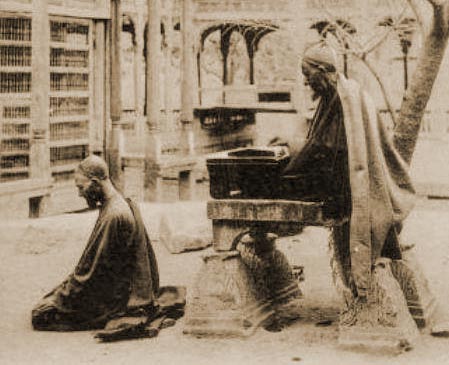

(Pirs in Kashmir were holding the highest status in social ladder, often linking them with rulers.)

After him, the mountaineer was introduced. He was a man of my own age, perfectly handsome; with a very mild and haughty countenance…I told him that I was a friend of the oppressed and a promoter of peace, that I deplored the state of war and perpetual uneasiness in which he lived, and that if he would promise henceforth to remain in peace, I would ask Runjeet Sing for the liberation of one of his wives and of his daughters, who were captives at Cashmere. He related to me his history, which affected me much, and I certainly will keep my word when I see Runjeet Sing again. But I am convinced that the best way for him to have got his wife and child back, would have been to have carried me as his prisoner into the mountains; and I take it very kindly of him to have left me to be the uncertain instrument of their freedom, instead of making me the assured pledge of it, as he might have done.

..Two men of my ambassador’s suite had been frozen to death on the journey; another had his arm broken; a horse had fallen down a precipice..

DJAMOU; October 3

(A sketch from Sikh rule offerring the common transportation of the elite.)

I left Cashmere on the 19th of September. The stupid Sikh who is at present in possession of the privilege of plundering that unhappy country (at the expense no doubt of disgorging into Runjeet Sing’s treasury at the end of his government) came the day before, to pay his visit of leave; he brought me, on the part of the king, a khelat, or dress of honour, of the value of fifteen hundred rupees (four thousand francs).

…Although I had fixed the day of my departure a week before hand. Sheikh Badar Bakhsh, my mehmandar, was not ready. This man is no worse than the other Sikh officers, but I hate him more, because, from the time he has been with me, I am better acquainted with him. He bought six women at Cashmere, two of whom he married before the Mullah, and it was the difficulty of transporting them beyond the mountains which detained him in the city.

… My caravan was much more numerous than on my arrival. Sixty soldiers formed my escort; fifty mountaineer porters carried my baggage, a few alpine animals were led in the rear…

… Gulab Sing is better obeyed at a distance than Runjeet Sing. His vizier received me as his master’s friend. All that I can desire comes as it were by enchantment. Plenty is in my camp; soldiers, servants, highland porters, are all lodged at the Rajah’s expense. The poor fellows had great need to pass through this land of plenty after the privations and fatigues they have endured since we left Cashmere.

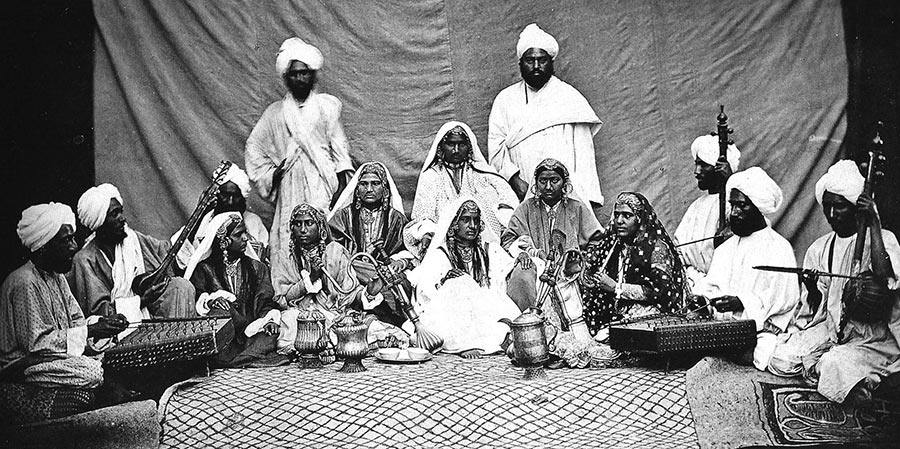

(A 19th century group photograph of men and women singers.)

The Rajah’s eldest son, who has remained here to receive me in his father’s absence, wished to come and see me last night on my arrival. He is a boy of fifteen, a favourite of Runjeet Sing’s. I received him only to-day. He interested me with his charming countenance and his modesty; at this age when children are opening into manhood, and the chance of what they will become is on the point of being decided, they interest me extremely. I therefore promised little Gulab Sing to remain here over to-morrow, in order to spend the morning with him on an elephant’s back, in seeing the environs of Jummoo, and preaching morality to him without his perceiving it.