A portion of the precious sixth century Gilgit Manuscripts discovered accidently by cattle grazers were taken to Delhi by Pandit Jawar Lal Nehru. A facsimile edition Gilgit Lotus Sutra was launched in Delhi recently for the first time ever, while the rest remains in Srinagar’s SPS museum in a precarious state. Tasavur Mushtaq reports.

Scattered from Srinagar to Delhi, the famous and precious Gilgit Manuscripts found a new lease of life. On Thursday, May 3, national archives launched a facsimile edition of the Gilgit Lotus Sutra. This set of the manuscripts written in Sanaskrit are considered to be the vital document about Mahayana Buddhism and offers a lot of information about the teachings of Buddha.

Scattered from Srinagar to Delhi, the famous and precious Gilgit Manuscripts found a new lease of life. On Thursday, May 3, national archives launched a facsimile edition of the Gilgit Lotus Sutra. This set of the manuscripts written in Sanaskrit are considered to be the vital document about Mahayana Buddhism and offers a lot of information about the teachings of Buddha.

Historically termed as Saddharma Pundarika Sutra that translates into the teachings of the white lotus and sun, these documents form the basis of the Tiantai and Nichiren schools of Buddhism.

Dating back to the sixth century, the manuscripts were discovered by cattle grazers in undivided India’s Gilgit region. These manuscripts are known to be the oldest record about Buddhism and thus predate Rajtarangni, the oldest historical record of Kashmir written by Kalhana.

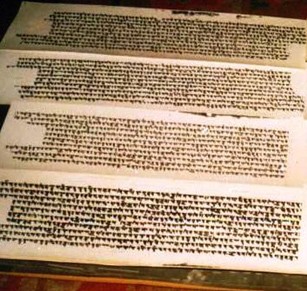

The process of discovery involved three stages near an age old stupa, and the boxes carrying them were immediately transferred to Srinagar durbar. Written on birch bark, the manuscripts took experts few years to understand what they were all about.

In wake of tribal raids, the then Prime Minister Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru suggested to the then emergency administrator Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah that these manuscripts being the oldest in history face a real danger, and part of them were shifted to the national archives in Delhi for “temporary safe keeping”. Afterwards Sheikh Abdullah tried many times to get them back, but he could not.

The remaining manuscripts in Kashmir are still awaiting proper preservation in Srinagar’s SPS Museum. Locked in a fireproof vault, mostly laminated, these scripts are usually neither being displayed nor permitted to be photographed. Interestingly, however, the part of the treasure that was shifted to Delhi in 1947 was maintained well.

“These are fragile assets and unless we have a proper system of their preservation, we do not permit people to touch it,” Mushtaq Ahmad, the Curator of the Museum said. “We will launch a formal programme in our own laboratory once we shift to the new museum building that has the lab facility.” A brand new museum set up for Rs 30 crores is ready for the housewarming, but the department is still indecisive if it would digitize the manuscripts.

The manuscripts that were shifted to Delhi are still indexed with the libraries department here. Then, Mushtaq said, archives, libraries and museums were a single entity. “Later when the Central Asian Studies (CAS) department was set up in the University of Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah issued an order and we transferred one cover of these manuscripts to the University.”

The SPS Museum is now left with seven to eight sets of the manuscripts and many of them were laminated by some German scholars using the technology that was available in nineteen eighties. “Within the means available with us, we keep these treasures the best protected,” Mushtaq said.

These manuscripts, museum officials say, have writings on one side of the page and are loose as well as tied together by coloured silk or twigs. Buddhist tradition prevents use of leather for binding sacred texts. Some miniature paintings reflecting the life and influence of the particular era are part of the manuscripts, they said. They said the unevenness, coarseness and granules on the surface of the leaves makes copying manuscripts almost impossible.

In 2007, these manuscripts bagged a cash reward of one lakh rupees from National Mission for Manuscripts (NMM). “It is this money that we intended to spent on the preservation plan [now],” Mushtaq said.

“It is high time we start making efforts to preserve them,” said M Salim Beig, head INTACH’s local chapter that is mapping the heritage resource across the state. “Let us preserve it as fast as possible and let people see it and benefit from them.”

A number of Kashmir scholars assert that the manuscripts written in Sanskrit and Pali offer details about the first resistance movements launched by the native Kashmiri Nagas against the onslaught of Buddhist rulers. “These are part of the documents defining Kashmir identity,” said M Yusuf Taing, Sheikh Abdullah’s biographer who is now Deputy Chairman of the state legislative council. “These need to be returned to the state.”