As one by one his pandit brethren deserted his neighbourhood in Haal Pulwama, it was a Muslim boy-turned-militant who helped Omkar Nath Bhat to stay put among the ghostly lanes of this village. Bilal Handoo recounts the curious case of patriarch of only surviving pandit family of Haal

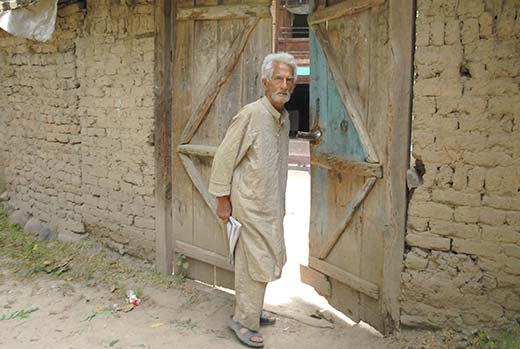

Pic: Bilal Bahadur

Much before Haal in south Kashmir’s Pulwama district got reduced into ghost lanes, an anxious Muslim boy one fine morning stepped into the beautiful landscape housing some eighty pandit families. It was early eighties. And Haal was bustling with life. That boy passed past traditional Kashmiri houses, walnut trees, grazing cattle and people busy with daily routine. He pierced the misty morning air on his way to the home of Omkar Nath Bhat, a Kashmiri pandit and his family friend.

As he stepped inside Bhat’s courtyard, he called the pandit patriarch. After hearing his name being called outside, Bhat walked on the porch of his house, and enquired: “Is everything alright, son?”

“Yes,” said the boy, looking disturbed and worried.

“I can see it from your face that something is bothering you. Just tell me, what is wrong?”

The boy took his time before replying: “You know, my maternal uncle wants me to learn carpet weaving. But I want to study.”

Bhat retorted the boy: “Yes, I know, how much serious you are towards your study, son.”

“Please, uncle. Do something. I promise, I will take my studies very seriously henceforth,” the boy then studying in 7th standard, pleaded before the pandit friend of his family.

Sensing sincerity in boy’s body language, Bhat promised him all the help. Being the friend of boy’s maternal uncle, he went to convince him to allow the kid to study. After great efforts that involved marathon motivation, Bhat finally convinced boy’s maternal uncle. The boy was sent back to school instead of carpet weaving handloom.

Otherwise considered as an average student, that boy went on to complete his graduation with a meritorious distinction. And just when he wanted to study further, the year, 1989, dawned. Like in other parts of the valley, that boy saw a horde of young men deserting their homes for ‘larger than life’ cause. Most of them were going for arms training. It was a blend of both temptation as well as sentiment that also drove the boy (then a grown up youth) on the popular track.

Meanwhile, the news broke out in Haal: 73-year-old veteran communist leader Abdul Sattar Ranjoor has been gunned down inside his home. It was March 23, 1990. Some gunmen had barged into his house in Kegam Shopian and killed Ranjoor on the spot. His killing triggered panic among Kashmiri pandits. “Most of us thought: if they [militants] can kill a Muslim leader, then we can’t be spared either,” said Bhat, a grey old man in his late seventies, sitting on grassy patch outside his medieval house in Haal.

As panic peaked in pandit community, Bhat witnessed a slow, but “heart-wrenching” disintegration of Haal. To begin with, some five pandit families fled in the dead of night. “Those who left didn’t even bother to inform their neighbours,” said Bhat, a skinny man whose blue eyes shone while recalling the quarter-century-old “nightmare”. While flashing a toothless smile, he resumed: “One departure led to another till 75 out of total 80 pandit households in Haal were abandoned.”

The remaining five families stayed put amid the lingering sense of fear. One family among them was Bhat’s family whose patriarch had superannuated as the horticulture officer on March 1, 1990. With no salary and pension, Bhat along with his wife, two sons and a daughter, decided to stay back. “I had no alternatives,” he said. Meanwhile, two of his grandchildren playing cricket nearby interrupted their play to hear out their grandfather. “I thought it is better for us to die in our own home than in the heat of Jammu.”

But staying back in the atmosphere of “fear and intimidation” was akin to “nightmare” for him. One day in early nineties, some masked men took him out of his home. They asked Bhat to assist them to trace some address in the area. He took them where they wanted to go. Upon reaching there, they uncovered their hands carrying guns. “As they displayed guns, I thought: I will be dead in a next few seconds,” Bhat recalled. “But to my surprise, they [militants] politely asked me: ‘Are you alright? Is anybody bothering you? Do you need anything?”

To his ill luck, some local army informer had spotted him while conversing with militants at a stone’s throw from his home. And soon, Indian troops showed up at his residence. It was a frozen January evening and Haal was simply haunting. “They [troops] grabbed my hand and took me outside my house,” Bhat recalled. “They asked me: ‘Who were those militants? And, why you didn’t inform us about their presence in the area.’ I replied: ‘How could I? They carry guns just like you. In either case, only I and my family have a reason to shiver with fear.’ ”

“Now, I want a favour from you. But please, promise me, that you will fulfill that,” Bhat told the army officer who grew curious. “I will make my five family members to stand in a single row. Just do us a favour: pump your five bullets inside us and end our nightmare forever!”

Somehow the army officer felt a sense of pity for Bhat and let him go. But before he allowed the ‘wretched’ pandit to go, the officer, quite sternly, warned him: “This is your first and the last chance. But don’t expect any mercy from me next time!” The army officer’s words kept echoing inside Bhat’s mind while returning home in what he called “the darkest night of his life”. “His parting words made me feel that I should also leave to avoid any such intimidations in future,” he said.

Bhat said that as the confrontation between armed Kashmiris and Indian troops escalated in the area, his house figured frequently on search operations. As the same plight persisted, the urge and resolve to flee the valley became strong in him.

But something motivated him to give up the idea of migration.

One day while returning from the market, Bhat saw a familiar face walking towards him on the street. To his astonishment, the man was smiling at him from a distance. Wearing pheran and sporting a long flowing beard, the man was escorted by gun-cocked youth dressed in fatigues. As he inched closer, Bhat identified him. He was the same boy who had sought Bhat’s help that morning some years ago for resuming studies.

Bhat could see that he was no longer a boy; rather, a full grown up man. But he was no ordinary. He had become the area commander of some militant outfit.

“You have stopped visiting us,” Bhat told him, carefully weighing his words.

“Don’t be so formal with me, uncle. I am still the same boy for you,” the boy-turned-militant replied.

Bhat sensed a strange surge in his confidence with the reply. Moments after, the man again said: “It isn’t that I have forgotten you and your address. I know, my visits will license Indian troops to harass you and your family quite frequently. And that is something, I don’t want.”

Bhat only kept exchanging smiles with the man who was speaking with both sum as well as substance. “Just drop a message at my home, if you need anything. I will be more than happy to help you out,” the man said before bidding Bhat a good-bye.

After that, the help kept pouring for Bhat family. He said that militants active in and around Haal always threw their full “support” behind him and his family. “They would enquire quite frequently: whether we have money, rice and other essential commodities,” he said.

The support from the otherwise “anti-pandit” labelled militants helped Bhat and his family to restore their calm of mind during the disturbed period. As peace for the only surviving pandit family of Haal started building up, a sense of normalcy prevailed. Bhat then married off all his three children, one by one, with the “support” of his Muslim neighbours. His elder son Ashok Kumar, 40, is a clerk in the postal department; while his younger son Maharaj Krishan, 38, is a government teacher.

Haal, where abandoned and weathered down pandit households invoking a sense of nostalgia, reverberates with life, love and laughter at the moment. No threat perception is derailing the play of Bhat’s grandchildren who often play hide and seek inside those abandoned houses. And on the landscape dotted with walnut trees, they love to chase each other and play cricket.

“And all this reminds me of that boy-turned-militant,” Bhat said. “I don’t think, today, I could have been watching my grandchildren play in Haal, hadn’t he [militant] supported us when it was needed the most.” And with that, he again turned his face towards his grandchildren playing cricket nearby and smiled.