Roads and plenty of cars is a recent phenomenon. In this 1954 travelogue, Pearce Gervis explains how the huge floating gardens, rations and the devotees to Hazratbal chiefly used the abundant waterways

After a while we came upon the mainstream which goes through to the lakes, the weeds had been cleared to some extent here; possibly the constant traffic up and down had made it impossible for them to spread, though in places reeds had taken their place, to be broken only by the great flat leaves of the lotus which are prolific on the lake. With the fall of the year these leaves slowly wither, the flower pods stand up alone above the water, and as we came upon them two children in a punt pulled alongside our shikara and offered first to us and then the boatmen, bundles of lotus pods which are a vegetable in Kashmir. Way back by the reeds we watched a man standing up in a punt and plunging a pronged pole into the bed of the lake, lifting it he brought up to the surface a long white thick growth; it was the root of the lotus plant, known as nadru, again known as a vegetable and much used in winter by the people of the city.

Every now and then little brown water hens would half-fly half-scull over the weeds away from us as we went slowly on. In places we came on dozens of large dragon-flies, some light blue, others yellow and yet more with red bodies, their colours seeming to have melted into their near-transparent wings, as for a while they hovered, then darted away; swallows wheeled round overhead when we came near to a house, which was obviously their home. The canal banks were a mass of colour, in parts white with clover, blue with forget-me-nots and yellow with the hanging cucumber, marrow and melon vines which had been planted there at the water’s edge, whilst in other places they had been overgrown and were mauve with convolvulus, and red with roses which were wild, but the blossoms double, the petals of some being red inside and orange on the outside.

Three Stones

We came upon a space clear of rushes, lotus and water weeds. An old fisherman was baiting a line of hooks as he sat in his shikara, which his small granddaughter was keeping out of the way of others passing. Here channels crossed, and standing erect on a small island in the middle was a short, circular column of stone. Another shikara had moved towards it, I overheard the pundit in it, who was showing his friends round the valley, telling them that it was but another idol similar to that on the Takht, the rounded top having been worn flat by the annas placed there by market gardeners on their way to the city in the hope that by so doing they would secure good prices for their produce—advance commission to the gods.

When this shikara had gone off, our boatman moved forward and explained that what we had heard was what the Kashmiri pundits always said, but that the people of the valley knew differently, for there were three stones in all, one also on either bank. The one on the right bank has a pointed top and was once a banker who used to charge more than thirty-three and a third interest on loans, the one with the flat top was a mat-seller who, sold mats by a measure which was a fifth short of the correct amount, while the other was a milkman who mixed the water of the canal with his milk. The gods had heard and seen these wicked men doing these things and as a punishment and a lesson for all time to the people, had turned them into stone; so they stand until this day.

Pearce Gervis has been an interesting British resident. He first studied law, then studied ground aeronautics at Oxford and joined the Royal Air Force. Then, he enrolled himself as a student in the London Hospital Medical College. He abandoned everything and started breeding poultry and wrote a guidebook to poultry breeding. In 1938, he returned to the Royal Air Force and served in Europe, West Africa and Asia. It was his posting in undivided India that he wrote the book on Kashmir.

Use of Home Space

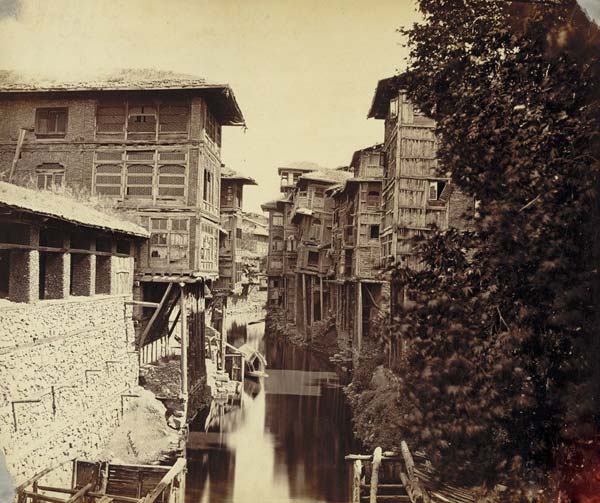

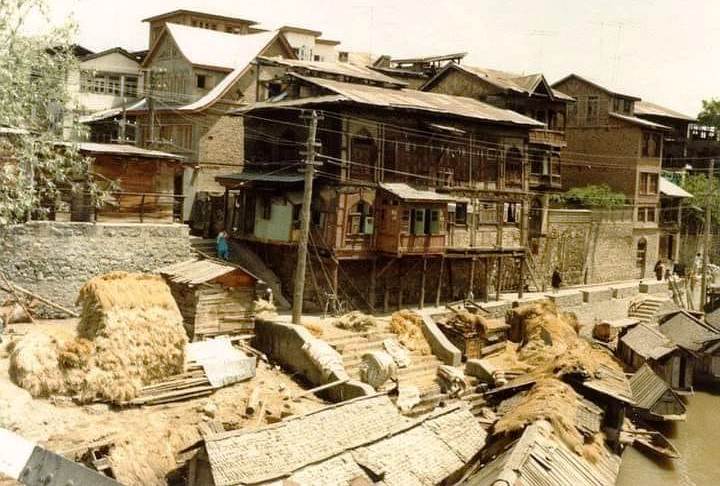

We went on, passing here and there a farmhouse with its buildings nearby. These are all the same, build of wood, the ground floor being used as a sheep and cattle pen, the first floor as living quarters for the farmer and his family, and the roof, the gable ends of which are left open, set aside as a store for winter fodder, so that when the sheep are shut below them with the fodder protecting the roof, the farmer and his family are kept warm during the winter months.

Only a very few of the houses had glass at the windows, most were wooden-shuttered, some had tattered pieces of sacking or brown paper, which had closed the windows the previous winter and had been torn down with the coming of spring. There was no sign of a chimney stack, and the roofs were either boarded or covered with earth and grass, just as are most of those in the city. It was a Dutch traveller to Kashmir from Antwerp who in about 1625 mentioned that onions were then grown on the roofs of the town houses.

In the walls of the houses we often saw circles with a hole in the centre in and out of which bees passed. These were the hives used in the valley. They are made of earthenware and rather like a two-foot-long chimney-pot with a lid on it, or to those who garden; a better description would be a rhubarb forcing pot. The hive is set with its base against the inner wall of the room, a hole or holes being bored through for the bees to leave and enter the pot, while the lid is sealed with clay.

The Kashmiri feeds his swarms throughout the winter, but considers the warmth of the room should be sufficient to keep them alive during the cold days; unfortunately it is not and many die, but they do not seem yet to have learnt a lesson. The bees are remarkably tame there; the peasants even resort to tying the queen bee with a cotton from her leg to the comb when they think she is likely to follow the other queens from the hive; often three or four swarms issue from the one hive. To remove the honey, of which two harvests are gathered each year, the lid is taken off, smoke blown in to drive the bees from it, and the combs then cut out.

Floating Gardens

We came upon the floating gardens, a unique feature of the lake. At first, I imagined them to be dry land with strips of water between them, and in fact they do become so after many years. These are made by cutting off from the side of the marshland a long strip of matted weed and bulrush bed some twenty yards long and a yard wide; the under part is also cut away so that the portion is about two feet thick.

This is then towed by a punt to the desired position and anchored there by poles being driven into the lake bed at the corners. To this, further weed, which has been hooked up from the bottom of the canal or lake, is added, being sandwiched between layers of mud and earth. It is manured and added to each year with rotted weeds and canal silt.

These floating gardens require no labour expended on them in watering the crops, and grow such vegetables as cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, tomatoes, and such-like whilst the more solid ones yield peas, cabbages, cauliflower, and even beets, onions and potatoes.

A few days later, we watched one being moved. For this two punts were used, one on either side as it was being poled down the canal to another position. At first not noticing the punts, it shook us a little to see a lump of land complete with cultivated plant life bearing down on us. They say that occasionally one farmer steals another’s floating garden. It is unusual though, and they are seldom moved from one place to another.

That day we came upon a punt deep in the water which was almost flowing over its sides. It was piled high like a hay-cart with weeds which the man standing at one end was lifting with a hooked pole from the bed of the lake and slopping into the punt. At the other end sat a small boy with an ordinary paddle with which he was scooping out from the bottom of the punt the water which drained through from the wet weed into pit at his feet, while at the same time he was keeping the punt out of the way of the traffic.

The Stone Bridge

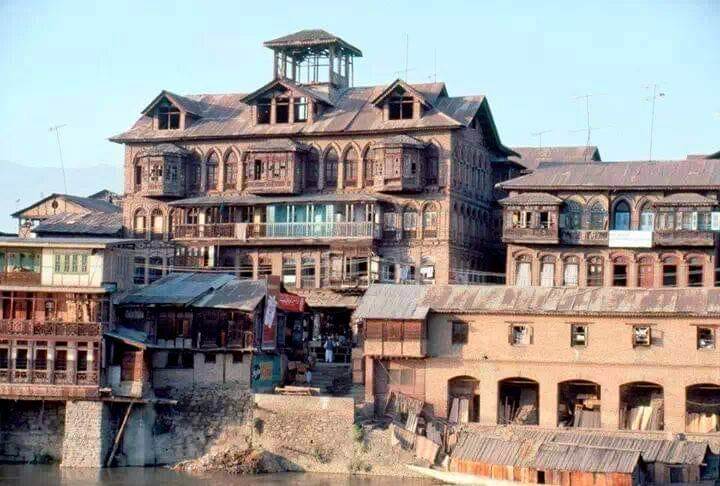

Further along we came on another village with its old stone bridge crossing the canal and all the houses, some many stories high, crowding on each other and the waterway as though every foot of land was precious. At one flight of wide stone steps men were busy washing live sheep in the water, at another boys were washing the newly embroidered gubbas in order to bring out the colour to its best before sending them on to the shopkeepers; we tried to buy from them but strangely enough they refused, although they could have had from us a much higher price than the trader would have given.

KL Image: Bilal Bahadur

We went up the waterway, through the channel cleared by the frequent passage of shikaras; on the right there is a large island on which are grown Lombardy poplars. Just where the channel narrows before widening out again, a most magnificent Chinar stands out from the tip of a small island with a house built near to it, the branches of the tree spreading out so that they cover half the waterway, its roots protected by a stone wall.

There must be a perfect view from here during the evening lights, with the lake stretching out to the far mountains the colours of which change with the setting sun and the rising moon, and the occasional light on the water from a night fisherman’s shikara, while across the sky come the dark shapes in formation of flighting night herons which live in the Chinar grove near to Hazrat Bal.

Hazratabal

Eventually we found ourselves on the lake and close upon that particular village with its spread of stone steps leading up: from the lake.

A little over to the left of the village is a mosque which is the greatest shrine of the Muslims in Kashmir, for within rests one of the Prophet’s hairs. This sacred relic is held on high and shown to the people on certain days of the year. It is recorded that it was brought to Kashmir by Khwaja Nurdin from Bejapur in ad1700. It is also said that one lac – that is one hundred thousand – rupees were paid for it.

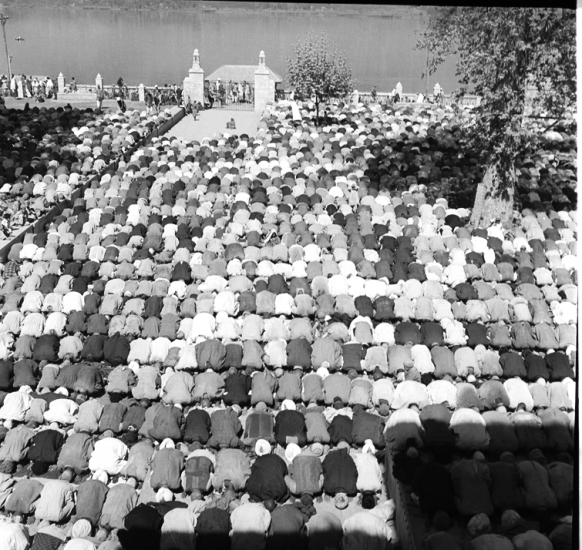

During recent years the outer courtyard has been rebuilt with a wall of limestone and paving stones. Still the old Chinars and willows remain to shelter the masses of Muslims who congregate there always on Fridays, but many more on the special occasions, then they number thousands wearing their best clothes, the children with gold embroidered, brightly coloured velvet hats shaped like page-boy’s pillboxes, but worn straight on the head; for these occasions, new clothes must always be worn.

The men outnumber the women by ninety-nine per cent, most of the women having to remain at home although they may not be strictly in purdah. Just a very few may have come in the hundreds of shikaras, which tightly pack the steps, but they stop in the boat covered in their burquas, the smaller children either remaining or occasionally running back to them. A few will venture up the stepway to the many shops which sell sweets and toys on all festive occasions, some may examine pieces of cloth, keeping their backs to the masses and only half-uncovering the face as they finger it. They imagine that cloth purchased on such a day and from such a place cannot fail to bring good fortune with it.

The men and young boys go forward, they stand in long rows in the courtyard, and following, repeat and perform their prayers, all standing with heads bowed, hands clasped loosely before them, all holding their hands to heaven, all going down on their knees, all touching the ground with their foreheads with eyes closed in prayer. There may be a few purdah women of the poorer men standing at the very back of the multitude, occasionally a courtesan will be seen; as so happened we saw one arrive in her private shikara with a beautiful young ayah – or maid – sitting at her feet, and being paddled along by four handsome muscular boatmen. The woman beneath the canopy which had curtains of gauzelike material and cushions of silk, wore heavy make-up, bright red lips, blackened eyes; gold tissue was worked into her expensive clothes, her red-tipped fingers were flashing with rings, her arms jangling with gold bracelets, whilst round her neck were ropes of pearls; she reeked of scent.

As she was helped from her shikara I saw that she was stiff and bent with age. The manji told me later that she was a famous character, having a fabulous fortune which by speculation she had increased ten-fold since the death of the millionaire merchant who had kept her.

It was said, but could now never be proved, that she had caused him to send his four wives from the house, and after discovering where his wealth was hidden, had killed him slowly by feeding powdered glass in his favourite cakes which only she could make. But she was now getting near to the age when death overtakes, and of recent years had often repaired to the mosque.

At first, it had been to the Pathar Masjid, The woman’s Mosque, but one who had wished her ill – it is said one of the wives from whom she had stolen the inheritance – was always waiting at the gate to offer her some of the same kind of cakes in which she had fed their husband the glass. So now her pilgrimage was to Hazrat Bal where, as we followed, we saw she was well received, no doubt paying heavily for such attention when she prayed for her own soul and those of her three sons who had died a year after each other on the even of Id – the great Muslim festival.

The inside of the mosque is heavily decorated with hundreds of coloured glass and brass lamps dripping from the lofty ceiling, and thick Persian carpets covering the entire floor, but none are as beautiful or gorgeous as those in the Shah-i-Hamdan mosque on the Jhelum River.

To one side is the famous shrine, the entrance made low so that those who wish to see the hair of the Prophet must go down on their knees to do so. Inside the glass case which is lighted, there are many hanging lamps and coloured globes, on its floor other decorations.

Working our way round, by keeping first to the edge of the lake and then through a maze of waterways, we eventually came out to that part of the Dal Lake known as the Gagrabal Lake, having on one side a stone wall covering the Boulevard Road at the lake edge, and on the other rows of houseboats which are as though shunted into small single docks, the verandah ends facing on to the wide clear waterway to the Dal Gate and the Boulevard, the bedrooms protected at the back and sides by narrow strips of land which are covered with overhanging willows.

Here I found that whilst we had been away the manji had brought our houseboat and cook boat to a new ghat for a few days, it being a favourite and convenient site for visitors’ boats during the spring and autumn weeks when they wish daily to visit the Mughal gardens or swim in one or other of the lakes.

(The last of the two-part series on the Kashmiri people living in water bodies, these passages were excerpted from the book This Is Kashmir by Pearce Gervis that Cassell & Co published in 1954)