The abundant colleges and teacher-scarce education department has lead the department to use and abuse almost 1900 teachers as contractual lecturer for more than 15 years. Now, they have been disengaged in utter disregard of their contributions and status, reports Umar Mukhtar

Waheed Ahmad, 40, leaves his home every morning to catch a cab to reach state run Degree College at Chrar-e-Sharief, almost 30kms from his Pulwama home. After marking his attendance on a separate sheet of paper, not the official ‘arrival register’, he starts killing his time for the whole day. He has no work to do. He is accountable to none.

With an MPhil degree, Ahmad has been serving Jammu and Kashmir’s Higher Education Department since 2004. He is a ‘contractual lecturer’, who has been teaching history for a decade and a half and has served various institutions. All of a sudden, he and his entire tribe have been grounded. They have been verbally communicated that their arrangement is over: they have no work to do, and no pay to take home. Now they are planning to challenge it in the court of law.

Recently, when the University of Kashmir held the Under Graduate examinations, those supervising and superintending the exercise were teachers from the secondary and middle schools. The ‘contractuals’ were around, sitting idle and were not involved.

“In 2004, when I was selected through a proper procedure, I got felicitations from all of my relatives, acquaintances and friends,” said Ahmad. Since then, he is a lecturer. In reality, however, Ahmad’s fight for his identity and survival in the department never ended. After putting in more than 15 years, the department has “verbally” disengaged him. Till August 5, Ahmad was teaching students routinely and getting a salary of Rs22000. As he resumed his ‘duty’ later, the principal asked him and many other contractuals that they are disengaged. Since then, Ahmad has not earned a penny. “In 2004 when I joined the college I was getting Rs8000. Gradually it increased.”

Ahmad is not alone. Of the 1900 candidates across Jammu and Kashmir, around 1200 are from Kashmir. They all stand ‘disengaged.’What makes the disengagement suspiciously painful is that there is no formal order. The decision was conveyed verbally from top to bottom.

The disengagement has devoured their social identity. “People know me as a lecturer,” explains Ahmad. “How I will tell them after 15 years that I am not. Instead, I am jobless.”

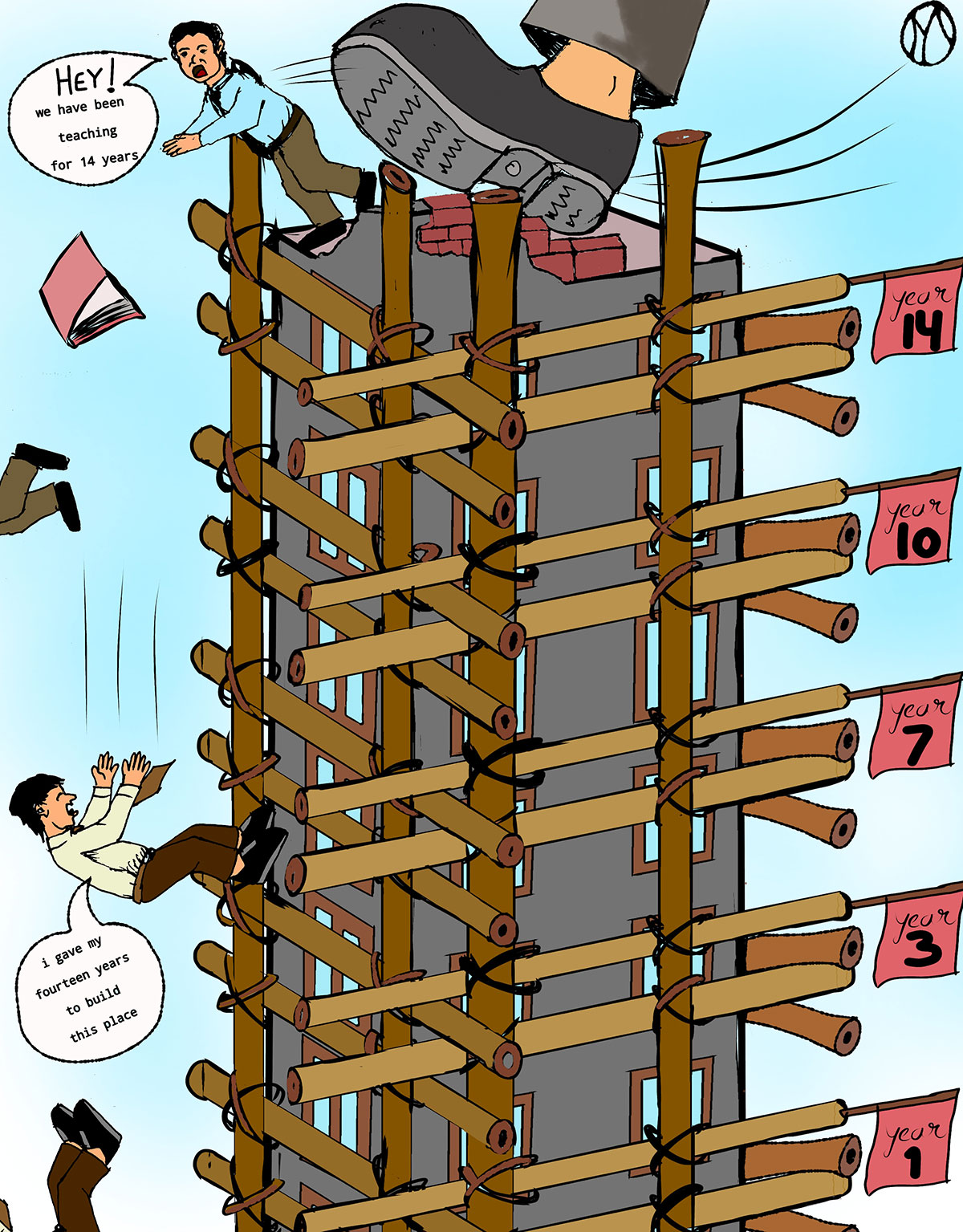

On basis of the “assumed” status, these contractuals have built their lives –married, have kids who know that their fathers teach in colleges. The disengagement has crumbled their ‘house of cards’.

In 2010, under the erstwhile state’s service regulations act, when the services of all contractuals, ad-hoc and need-based employees who had put in seven years of service were regularized, the college contractual lecturers were left out. Soon, their department changed the nomenclature: ad-hoc lecturers became contractuals and contractual lecturers were re-designated as teaching assistants.

Contractual lecturers are a new innovation of the Jammu and Kashmir’s education department. Since the government runs too many colleges, it lacks the staff. Every season, it hires from a lot who prove their credentials every season. They are being paid for the work they do and disengaged for the winter, and re-hired once the academic season restarts.

When the candidates submit their applications, some of new applicants have high percentages. Under the system in vogue, the seniors do not make it to the list.To this bizarre scheme of meritocracy appointment, Ahmad was a victim.

In 2016, Ahmad could not make it to the list. “I was shocked when I was told that I am not figuring in the list.” How he spent that year explains the crisis the people like Ahmad face.

Ahmad, however, did not tell anything to either to his parents or to his newlywed wife. So to keep his secret, he was dressing up routinely in the morning and spending his day at his friend’s shop. At 4 pm, he would routinely reach home, giving impression to wife and parents that he came from the college. After he spent his last penny and was on the brink of bankruptcy, Ahmad joined a private school in another district, DPS Sangam for Rs7000.

“There were schools in my district as well but I was not comfortable there,” Ahmad said. “I would get exposed and that will destroy my life.” In order to protect his secret, he would rarely meet people, fearing his lies might get exposed.

Next year to his luck he could manage it to the list.

But 2016 was just a year. Post disengagement, Ahmad has his life to manage.

Now, Ahmad, with almost other 600 candidates, has approached the court that has given them a temporary relief. The court has directed a status quo, asking the department to treat them as employees till there is not the disposal of the case. The college permits them in, gives them some space to sit and kill their tie. For their own satisfaction, these contractuals mark their own attendance for their own records.

Since they have not been paid since August, all of them are in mess.“I have a family of four members to manage,” Ahmad said.“I cannot afford the admissions of my kids in a private school.” Ahmad has a daughter 6 years of age and a three-year-old son.

Abdul Samad Wani, 53, has doctorate in Arabic and is NET (national eligibility test) qualified. Since 1997, he has been a contractual and his last “posting” is the state run college at Khan Sahib.

“We are not given any task in the college,” Wani said. “We are like the outcasts. Despite the court order, neither we get salaries nor are we treated employees anymore.”

Till 2014, Wani used to figure on top of the seasonal list. Not anymore. “Now I stand almost at serial 40. There is no privilege for the services we rendered to the department,” he said regretfully.

The higher education department has a nodal officer who scrutinizes the contractual candidates according to the merit. “In 1997 I got 60 per cent which was best of that time. How can we compete with the new generation that comes with a percentage of 80 to 90 per cent marks?”

Competing with the candidates who have been their students at some point of time adds the element of humiliation. To fight the vagaries of his job and life, Wani said he did resort to things, he usually should not have done. Once when he required some money to get babyfood for his kid, he begged.

In 2016, when he failed to make it to the list, he went almost 50 kms away from his home, and worked as a paddy harvester. It triggered a drama as the paddy field owner’s son recognised him.“We cried like kids,” Wani said. “He took away the sickle from my hand, gave me some money and dropped me at my home.”

“When I joined the department, my daughter was just a year old,” said Wani in hate and anger. “Now she is 25 and I am told to get out of the college.”

Unlike men, the female contractual lecturers are in a worst condition. Lovely, 38, with MPhil in Urdu is presently posted at Pulwama. She shuttles more than 60 kms a day in coming and going from Srinagar.

Off late, Lovely said she is facing lot of music and taunts: ‘Why are you still dependent on others? File kouetwache? (Where is the status of your job file?)’ She even heard her students describing her as the Madam who wears a same dress daily.