When Pandit Nehru sacked Sheikh Abdullah in 1953 and sent him to jail, the heir apparent Indira Gandhi was desperate to visit him in jail. Historian Ashiq Hussain Bhat revisits the least reported event in Kashmir history in the backdrop of fresh evidence that was published last month.

In August 1953 Prime Minister Nehru got Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, the ‘Prime Minister’ of J&K disgracefully deposed and lodged in jail on the charge of conspiring against Indian sovereignty. In the din of the crisis, nobody spared a moment to understand that India owed its sovereignty over Kashmir because of Sheikh.

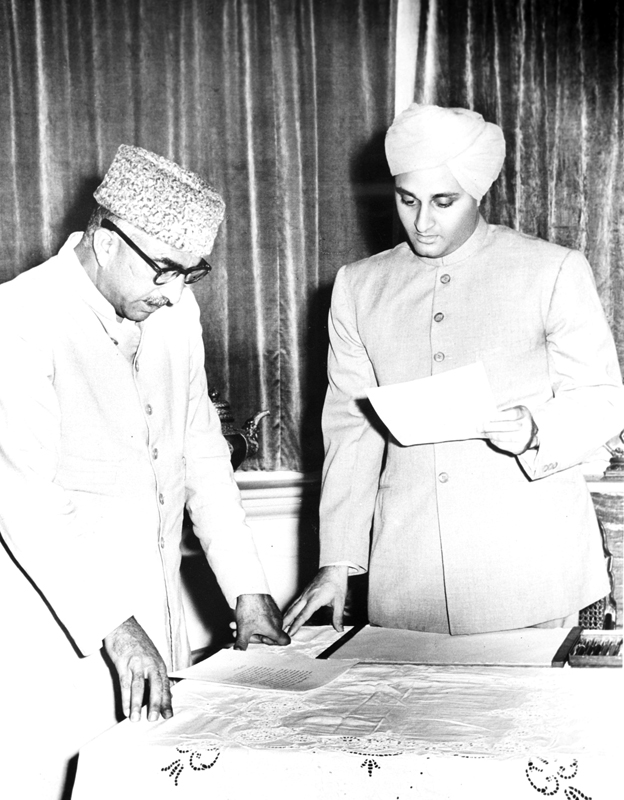

Way back in June 1939 when Sheikh, sacrificed, at the altar of Congress Party, the ideals for what All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference stood, Nehru had described him in his various addresses to Kashmiris’ as “a daring, farsighted statesman who had the capability to properly lead the masses of Kashmir, and who had, despite odds, led the mass movement from its narrow parochial and communal outlook towards the path of nationalism (see page 264 of Aatashi-Chinar)”. In 1953, however, he got the same Sheikh disgraced for opposing complete assimilation of Kashmir into India. His agents hurled all kinds of accusations against Sheikh. Bakshi, the new Premier, accused him that he had prepared a revolt for the creation of Independent Kashmir (pp. 600-01 Aatashi-Chinar); and that he had colluded with Pakistani agents. Nehru presided over national Government of India for well over a decade since Sheikh’s incarceration – Sheikh spent a rotten life in various jails of the country. Nehru showed no concern whatever towards him.

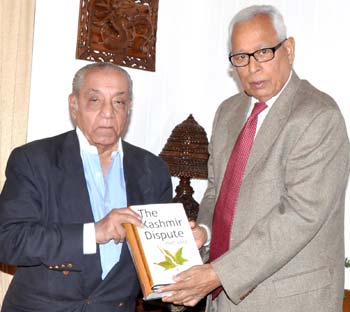

There were few people in India who sympathized with Sheikh Abdullah. Apparently, one of them was Nehru’s own daughter, Indira Priyadarshani Gandhi. Soon after his arrest Indira Gandhi sought permission to meet Abdullah in jail which threw Prime Minister’s Office in jitters. Though it was being talked about in whispers for all these years, this fact was brought to light by the top-secret letter written by OM Mathai, Nehru’s Private Secretary, published recently in his book Kashmir Dispute 1947 – 2012 by Kashmir expert A G Noorani.

“I have given considerable thought to your proposal,” wrote Mathai, asserting at the end that he typed the letter personally. “Two days ago, I asked you a direct question purposely and I was happy to note that in your judgment of the problem the personal attachment to Kashmir as an ancestral place and as a beautiful valley did not play an important part. To me, that attitude is very important because sometimes supremacy of the head over the heart is essential.”

Mathai then goes on informing Indira Gandhi about the issues that led Nehru to take the “realistic decision”. “It is a patent fact that the speeches and activities of Sheikh Abdullah during the past few months have been the effect, direct and indirect, of encouraging the pro-Pakistan elements among the Muslim population of the State,” the letter says. These speeches, as was reported to Delhi by intelligence services and army, had made pro-Pakistan elements “highly vocal” and encouraged them to function in the “open freely”. Besides, Mathai asserts that Sheikh and Afzal Beg had prevented Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad from acting against infiltrations from across.

The other charge was Sheikh’s rejection to Nehru’s invitation to come to Delhi for talks. This was seen as his disloyalty to the man (Nehru) who “built up this man to the point of his being somewhat inflated”. Mathai even says that “in the last two or three months or more” there was “no government, in the generally accepted sense of the word” functioning in Kashmir.

Mathai letter is clear that Indira believed her father, the Prime Minister of India, decided ousting Sheikh because “the wrong kind of people” influenced him. “I find it difficult to agree with you entirely about how PM was influenced by the reports of the wrong kind of people,” the letter says.

Then the letter offers six reasons why Indira should avoid meeting the detained and dethroned Sheikh. Firstly, it was a “possible embarrassment to the present regime in Kashmir”. Your action, the letter says, “might even unnerve them.”

Secondly, it would take a lot of efforts to keep it secret from the press. Thirdly, possible hostile attitude on part of Sheikh Abdullah but it would not be a problem because “you are taking a risk.”

Fourthly, the attitude of Begum Abdullah. “I would not brush aside her reaction lightly.”

Fifthly, “you are not going to meet Sheikh Abdullah purely in your personal capacity” because “the personal capacity business is anyhow a difficult thing for people in certain positions.” At the same time, Mathai wrote to her that she can neither go on anybody’s behalf nor as an “emissary to affect a rapprochement.”

Finally, Mathai suggested her two things. First to consult the Prime Minister and second, for any worth-while talk with Sheikh Abdullah, “you should have a very clear idea as to what the Government of India’s intentions regarding Kashmir policy.” He suggested her to talk to Moulana Azad, Dr Katju and Rafi, who are shaping India’s Kashmir policy.

Then, the policymakers in the government of India were not thinking about Sheikh on the same lines as they had done immediately before and after 1947. The letter says it very clearly and source to this information was Vengalil Krishnan Krishna Menon (3 May 1896 – 6 October 1974), then the most powerful person in the government after Nehru and key to Kashmir policy.

“Krishna told me that from such talks as he had with him (Sheikh Abdullah)…he appeared to be extremely muddle-headed,” Mathai writes. “Krishna did not get a sensation that Sheikh Abdullah would be a reliable person in a crisis where his personal position was involved. In short, Krishna did not consider him to be a man of real substance.”

And what were Mathai’s views? “Personally, I have always felt that Sheikh Abdullah failed on the whole as Prime Minister of J&K state. He had no constitution fettering him in any way. He was a virtual dictator with a completely free hand,” the letter to Indira written on September 12, 1953, reads. “I think he was not very competent. I never got the impression that Sheikh Abdullah was a man of his word. His sense of honour was certainly different from my conception of it.” He goes on further: “There is a difference between a demagogue and a statesman.”

Despite the apparent concern that Indira Gandhi had manifested by demanding permission to visit Sheikh Abdullah in jail, the latter suffered significantly through the incarceration period till after a year of Nehru’s death when Indira Gandhi was herself firmly on the Prime Ministerial seat. Even then Sheikh Abdullah was not a free man. He had been jailed on May 8, 1965, the day of his return from Haj pilgrimage and remained incarcerated till January 1968.

In January 1971 Indira Gandhi’s Government served him an externment order in Delhi which prohibited him from visiting J&K. His externment remained in force till June 1972. It ended only when he bowed down to the diktats by proclaiming that “he never differed with Union Government on the question of the fact of accession but only on the question of quantum of accession (pp 835 Aatashi-Chinar)”; and that Pakistan lacks a locus standi on Kashmir (pp 837 Aatashi-Chinar).

Even after sending the Plebiscite Front movement to winds in 1972, Indira Gandhi did not concede Sheikh’s demand – that of being reinstated as Prime Minister of J&K. The days of state’s autonomy were over, already and a lot of water had flown down the Amira Kadal. She stated that the clock cannot be turned back. Resultantly Sheikh had to wander in the political wilderness for a couple of years more till his ‘hankering” after power got the better of him to get the throne from the back door.

Hardly had he served, post-1975-Indira-Abdullah Kashmir Accord, as Chief Minister for two years when Indira Gandhi dealt a fresh blow through provincial Congress headed by Mufti Mohammad Sayeed who withdrew Congress support from his government. Sheikh Abdullah, however, managed to enlist the support of national Government of India headed at that time by Indira Gandhi arch-rivals, the Janata Party, because of they also, despite their claims to the contrary, followed Nehru’s Kashmir policy to the minutest detail.

Indira remained at loggerheads with Sheikh, right up to the time of his death in 1982. She had resented re-establishment of National Conference in place of Plebiscite Front, and wished them to join Congress Party to place themselves at her beck and call (pp 853-54 Aatashi-Chinar).

In sum, both Indira Gandhi’s and Nehru’s relationship with Sheikh remained one of exploitation in which Sheikh Abdullah, for the simple reason of his personal political ambitions, was always at the receiving ends. But the show goes on, generation after generation.