Once the Delhi-Srinagar rapprochement sent J&K Congress to the backseat in 1975, Mufti Sayeed started experimenting with alternative ways of staying powerful. His chain of experiments continued till he ceased to be India’s Home Minster in November 1990. Bilal Handoo reviews 15 years of Mufti’s status as being Delhi’s powerful Kashmiri man

Much before her guards-turned-guerrillas gunned her down, the dauntless daughter of Jawahar Lal Nehru boasted: “All my games were political games; I was, like Joan of Arc, perpetually being burned at the stake.” Joan, a French military leader, defeated British during the Hundred Years’ War.

India’s Indira was playing a different game, especially in Kashmir – a go-getting political battle. Once she played her masterstroke, Kashmir’s ‘tallest’ leader declared plebiscite movement a “political wilderness”, binning it after 22 years of battle-hardened struggle. But she needed the “wily man” from Bijbehara to keep mercurial Abdullah in check and balance.

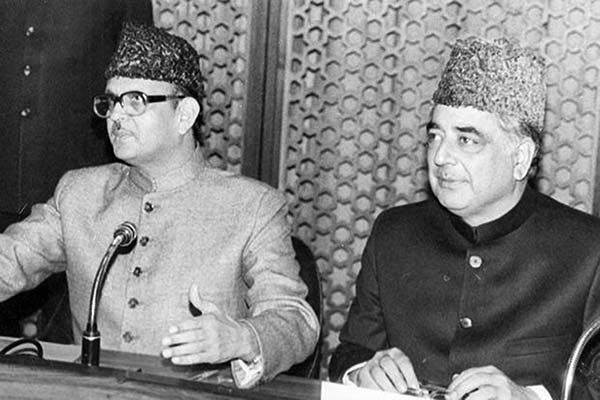

Before becoming Indira’s eyes and ears of Kashmir, Mufti M Sayeed, Abdullah’s archrival, was a silent spectator of 1975 Indira-Abdullah accord. The Congressmen of yore reckon that the accord provided political space to Mufti and an opportunity to know how he can manage an opposition while being part of the government.

While Abdullah became chief minister, Indira elevated Mufti—Syed Mir Qasim’s junior besides his right-hand man, as her state party chief. Mufti got the prized post after Indira glimpsed ‘cunning’ leadership skills in him. He was immediately tasked to rebuild the state Congress “to cut size to Abdullah’s stature”. Fearing renewal rant of autonomy, Indira wanted Mufti to keep Abdullah in a tight spot. Her paranoia was deep rooted in the realisation how she and her late father had toyed with J&K’s autonomy issuing 28 constitutional orders and implementing 262 Union laws in state from 1954-75 — the epoch when Abdullah was behind the bars. It was then, state Congress camp started simmering.

Behind the rage were Abdullah’s vintage anti-Congress rant and his signature snub politics. The disgruntled Congress chieftain beckoned ‘powerless’ Indira at Delhi. While conveying his displeasure over the state of affairs, Mufti convinced her to withdraw support from Abdullah government. But the ruling Janata Party didn’t wish to see Congress in power in any state, particularly in Kashmir—where they feared that the ‘fly-by-night’ Abdullah might resurrect the plebiscite movement if rendered powerless, again.

But Mufti had his own plans. By spring 1977, he was face to face with the governor LK Jha along with Indira’s state force. The Congress lawmakers had walked into the Raj Bhavan to withdraw support from Abdullah’s government with immediate effect. The fresh demand was to declare a new Congress government in state-led by Mufti. But Abdullah, previously ousted from power by his friend-turned-foe, Nehru, had matured enough to prevent Nehru’s daughter from repeating the history.

He shortly visited the governor, asking him to dissolve the house, and announce fresh elections in J&K. While the state slipped under the governor’s rule for the first time in history, Abdullah was seen in a vengeful mood to resurrect his lost aura.

By the time the last ballot of 1977 ‘fair’ elections was put to count, Abdullah’s NC emerged victorious, eradicating Congress in the valley, winning 47 seats of 75 Assembly seats. Among the losers was Mufti, defeated from his hometown Bijbehara. The poll crush was an ego-hurt moment for both Mufti as well as his madam. But there was no staying back for the former advocate, who buckled up to infuse a new spirit in his party.

Mufti straight away stepped into shoes of a Congress foot soldier, visiting places to build the base of his party. He would literally knock at doors, going village to village, asking people to join his party. Much of this campaigning was confined in South Kashmir. Mufti created pockets of staunch support for Congress through his astute politics, playing a role of a bridge between Delhi and Srinagar. It was then, Mufti became a person of hate and slogans were being shouted: Muftien Kabar, Kashier-e-Neabar.

At Delhi, Indira-led Congress swept back to power in January 1980. The news delighted Mufti. With PM Indira’s backing, he emerged as a rival power centre in J&K, always playing his cards close to the chest. He would issue permits, give cash assistances and register graft cases against Abdullah administration. All this was coming from the man who was perhaps the only opposition for Abdullah in J&K. By September 1982, Mufti lost his nemesis to cardiac arrest. In Farooq Abdullah, he got his new-fangled rival.

At the first go, Farooq replacing his father with Indira’s support considered Mufti a “great manipulator”. The temperamental Farooq never concealed his take on Mufti—whom he repeatedly described as Indira’s “creation” for “abusing” Sheikh Abdullah. But for Mufti’s proponents, Farooq’s remarks were always desperate to denounce Mufti’s challenge to Abdullah’s political dynasty. His opponents, however, believe that Mufti’s Delhi devotion was based on his desire to become J&K’s chief minister one day. “He had a suit tailored for his swearing in at a shop on Residency Road in Jammu,” Farooq would mock at the issue whenever raised, “and it’s been gathering dust there for decades.”

Amid this no love lost between Mufti and Farooq, Indira was hoping that Abdullah’s son would be departure from his father. But she was wrong about flamboyant Farooq known for his tongue-in-cheek comments. The second generation Abdullah badly disappointed her when he turned down her offer of alliance in 1983 elections. What Indira curtly did was based on Mufti’s direction. Even her own cousin became a villain in the coup de théâtre.

The iron-fisted ruler known for her ruthless rule, Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi faced controversies for her emergency rule in India from 1975 to 1977. During that period, her cousin Braj Kumar Nehru, an Indian diplomat was her articulate defender. He was convinced that Indira had no other alternative in the face of Jayaprakash Narayan’s call to the military to revolt. But the moment Nehru became Kashmir’s Governor, Mufti redefined the old maxim: Blood is not always thicker than water. Later, the man summed up his Kashmir experience in his autobiography Nice Guys Finish Second: “In Kashmir the stakes were so high that I did try and follow what happened in the next few months.”

It didn’t surprise Nehru when Farooq government was dismissed in a coup and replaced by his brother-in-law GM Shah. As a governor of J&K, Nehru was witness to the political play enacted by Indira based on Mufti’s script.

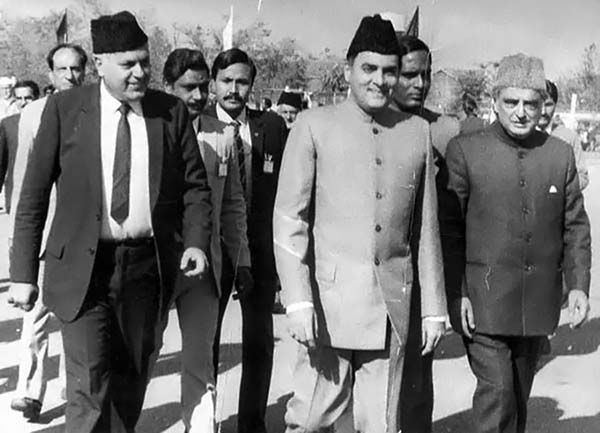

It had all started after Farooq’s alliance refusal forced Indira to unleash her full might against him. She did a week-long extensive campaigning in Kashmir with her loyal man, Mufti, who extensively air-travelled with her. Behind Indira’s adrenaline campaigning was Mir Qasim’s old catch—“whenever New Delhi feels a leader in Kashmir is getting too big for his shoes it employs Machiavellian methods to cut him to size.” But one Srinagar experience only heightened the “Mummy’s” aversion for Abdullah’s son.

During her public address in Srinagar’s Iqbal Park in the run-up to 1983 polls, Nehru writes, some people in the audience lifted their pherans and displayed their nakedness in an obvious affront to Indira. The act left Indira red-faced. She spoke to nobody, quite contrary to her usual behaviour, and entered her aeroplane. Behind Indira’s public shame, Farooq was an accused ‘nasty brain’.

But Farooq vehemently denied his involvement. “In the absence of any evidence to the contrary,” Nehru notes, “I fully believe simply because organising vulgarity like this would be completely contrary to his (Farooq’s) character.” The chief plotter and Indira’s principal adviser, Mufti Sayeed—the disciple of PL Handoo and the protégé shared the ideology of the conspirators (Bakshi, Sadiq and Qasim) of 1953—was fuelling this mindset, Nehru recalls.

Mufti shortly struck again with his league, accusing Farooq of being a secessionist, a JKLF member. He printed an old photograph from Farooq’s London days shaking hands with Amanullah Khan and called him a Pakistani agent and an anti-Indian. “The facts,” Nehru writes, “were that Farooq was the first honestly elected leader of the Kashmiri people who was totally Indian… unlike his father.” But the conspiracy nose-dived once the poll results were out.

Riding a sympathy wave after his father Sheikh Abdullah’s death, Farooq led NC won 46 of 76 seats in 1983 elections. It was a clear majority to him in state assembly. Mufti—then despised as being too close to Delhi, lost both seats: Bijbehara and Homshalibugh. But the defeat didn’t bog down Mufti, who staged a comeback by 1984 summer with his plan to pull down an elected government.

The plan was to bribe MLAs for defecting from NC to dismiss Farooq government. For this to happen, Mufti needed Governor Nehru’s support. But Mufti had stopped visiting him after sensing his closeness with Farooq. He used Indira to execute the plan.

One fine day, Indira complained to Nehru about Farooq’s anti-Congress and anti-peoples activities. “I said that no such reports had come to me,” Nehru writes in his autobiography. The next thing said by Indira was resounding thud to his ears—“Farooq is more dangerous than Jinnah!” Nehru heard Indira saying how Farooq had boasted that he would be responsible for the second partition of India. “The conveyor of the tales to the prime minister was obviously Mufti Sayeed—whose loyalty to India was unquestionable,” he writes.

As BK Nehru refused to be party to the scheme, Indira replaced him with Jagmohan on Mufti’s insistence. Jagmohan’s reputation based on emergency days was that he was a faithful servant of 1, Safdarjung Road. His role in butchering Muslims of Turkman Gate was well known to Kashmiris. He dutifully summoned Farooq and told him that 13 of his MLAs had defected, and that he was dismissed. GM Shah took over, not before intricate intelligence was involved and lump sum money was pumped in to buy loyalties, writes Nehru.

By 1985, Mufti managed to enter the state assembly after winning a by-election in Jammu’s Ranbir Singh Pura. A year later with Babri Masjid riots creating unrest in India, Mufti shared blame for engineering communal violence in South Kashmir’s Islamabad. The motive was to topple GM Shah’s government.

By then, Indira was assassinated. Her son and Farooq’s buddy, Rajiv Gandhi, sought to marginalise Mufti. The rationale was to revive Abdullah dynasty in J&K. Mufti was deputed on ‘union posting’—awarded a Rajya Sabha seat and union tourism and civil aviations portfolios. But the apparent promotion was actually demotion for Mufti: to keep him at bay from state politics. Soon Rajiv-Farooq Accord took place. Mufti opposed it saying the decision was taken by shrugging off seniors in state Congress circle.

While cooling his heels in Delhi and puffing cigarette in a gauche style, the disgruntled Mufti was busy telling a scribe shortly after the accord: “It has not been easy to be a Congressman in Kashmir. You have to develop a thick skin for the abuse and difficulties heaped on you.” Yet, Rajiv snubbed, sidelined him from state politics—the step that badly hurt Mufti.

In Delhi’s obscure political atmosphere, Mufti was awaiting a moment to bid adieu to Congress. Then, Meerut riots broke out. He blamed Rajiv’s “insensitive” approach for fanning out the violence. He resigned, returned home.

In a little while, VP Singh was sacked as defence minister from Rajiv government for speaking out against the Bofors gun scandal. He shortly raised an anti-Rajiv band, including Mufti, to start Jan Morcha movement. By October 1988, the movement took form of political party, the Janata Dal. The party won 1989 elections with Mufti winning UP’s Muzaffarnagar seat. In December that year, the National Front led by Singh conquered Delhi.

Singh became PM and Mufti, his HM—the first Muslim to ever head the ministry. More than on his merit, Mufti’s appointment was Singh’s way of showing that his was a secular regime. But, what happened six days later, redefined Mufti forever.

On the historic day of December 8, 1989, the then J&K’s Chief Secretary, Moosa Raza was a busy man. Upon reaching North Block, Mufti called him at his 10, Akbar Road residence. He had just received news of the kidnapping of his daughter. Raza saw a calm and collected father inside the room. “For a man who had received the news of his daughter’s kidnapping minutes before, he showed no sign of excitement or agitation,” Raza recalls in his memoir. “The only remark he made to me was, ‘I would not have been so anxious had they kidnapped my son.’ ”

Mufti’s second daughter, Rubaiya, a medical intern, was kidnapped in Srinagar by JKLF militant outfit, demanding the release of five militants—Abdul Hamid Shaikh, Gulam Nabi Bhat, Mohammad Altaf, Noor Mohammad Kalwal, Javed Zarger (later replaced by Abdul Ahad Waza)—incarcerated in the city, in exchange for her safe return. After twists and turns, the daughter finally returned home. Mufti maintained that releasing the militants was the state government’s decision. But the union ministers Arif Mohammad Khan and IK Gujral arriving in Srinagar with Farooq’s dismissal order in case he resisted the release contested his claims.

Soon after the hostage crisis, PM VP Singh appointed his railway minister, George Fernandes, as head of Kashmir Affairs Committee. But the move didn’t go well for Mufti, triggering rift between the two. The irate Fernandes favouring talks with militants soon made it public that Mufti was “resisting a solution” to the Kashmir problem.

But as rebellion began building up in valley, Singh considered appointing Jagmohan—the Indira’s man notorious for toppling 1984 Farooq government—as the state’s governor. While the Left opposed the move saying the “anti-Muslim” might trigger mayhem in valley, BJP and Mufti favoured the appointment. Even President of India, R Venkataraman had reportedly opposed Jagmohan’s appointment. In protest to his appointment, Farooq resigned and flew to England “to play golf”.

And soon, in his broadcast over the state-run All India Radio, Jagmohan Malhotra, who used only one name, said: “I have come here to rid you of your difficulties.” A confrontation would mean, he warned, “the card of peace could slip out of my hands.”

He did slip his “cards of peace” quite ruthlessly. His stint as J&K Governor (January 19, 1990-May 26, 1990) saw the Kashmir entering into a period of brutal repression. On January 19, 1990, he facilitated Pandit migration from valley. On January 20, 1990, CRPF opened fire on people protesting against Delhi and Governor Jagmohan at Gaw Kadal. More than 50 people were killed. On January 25, 1990, 25 civilians killed by BSF in Handwara. On March 1, 1990, 33 killed and 47 injured at Zakoora crossing and Tengpora as forces opened fire on protestors demanding the implementation of UN Security Council resolution. On May 21, 1990, at least 50 people killed as BSF fired on the funeral procession of Mirwaiz Maulvi Mohammad Farooq near Islamia College in Srinagar.

By May 26, 1990, Jagmohan was called back—not before making bloodbath as norm in valley. As home minister, Mufti defended Jagmohan’s Kashmir tactics brushing aside the killings, massacres. “By sending Jagmohan to Kashmir we made major gains,” Mufti said in an interview on June 30, 1990. “He set up this nucleus of officials to fill the administrative vacuum. And we established the authority of the state.”

Five days later that interview in which he gave himself a clean chit, saying, ‘I’m a soft target’, Mufti implemented the dreaded Armed Forces Special Powers Act in J&K. The law gave sweeping powers to forces, setting off years of widespread crackdowns, detention and torture. Mufti was “happy” with AFSPA because he consolidated his power.

Eleven months later, Mufti’s stint as Indian home minister ended after VP Singh government fell in November 10, 1990. He soon slipped into obscurity, but his home ministerial acts continued to haunt Kashmiris. Later, his political opponent, NC, termed Mufti alongwith Jagmohan as “brothers in crime”.

“Mufti Sayeed of 1990 filled graveyards after graveyards with our young men,” NC maintains. “As the Home Minister, Mufti is on record to have said that one bullet would be responded with 100 bullets. He ordered the security forces to shoot at-will and at-sight and slit the throats of hundreds of youth. These operations have been carried out under the code name of ‘Operation Tiger’, ‘Operation Eagle’, ‘Operation Shiva’ and ‘Catch and Kill’.”

During his years (1991-95) of political hush, Mufti was quietly working on his politics of accommodation, trying to bring Kashmir closer to Delhi, thus earning labels: “surrogate” of New Delhi, “collaborator” in Indian tyranny and “Indian by conviction”.

“What are your plans for Kashmir?” Mufti, saddled with the image of a soft-man-in-the-hot-seat, was asked during his June 1990 interview. Mufti replied, “Gary Saxena will deal with terrorism firmly. But it isn’t only a security problem. The civil administration also has to do its job.” That was a vintage Mufti almost sounding like playing games akin to his Madam Indira.