As the Jamaat-e-Islami workers are imprisoned across Jammu and Kashmir after the party was banned by the Home Ministry, forcing lot many to go underground, Masood Hussain traces the 10 key dates around which the party’s 75-year old troubled history revolves

Within days after the horrific Lethpora car bomb blast, the police started raiding the residence of Jamaat-e-Islami activists and rounded them up. In the first night, more than 100 were rounded up. The arrests continued for around 10 days when the Home Ministry issued a formal notification and banned the party for five years.

The MHA notification termed the party’s activities “prejudicial to internal security and public order” and insisted it was “in close touch with militant outfits and supports extremism and militancy in Jammu and Kashmir,” was involved in “anti-national and subversive activities” intended to “cause disaffection”. In case, the party’s activities were not curbed immediately, the notification said “its subversive activities” would escalate and it would continue to attempt “to carve out an Islamic State out of the territory of Union of India”.

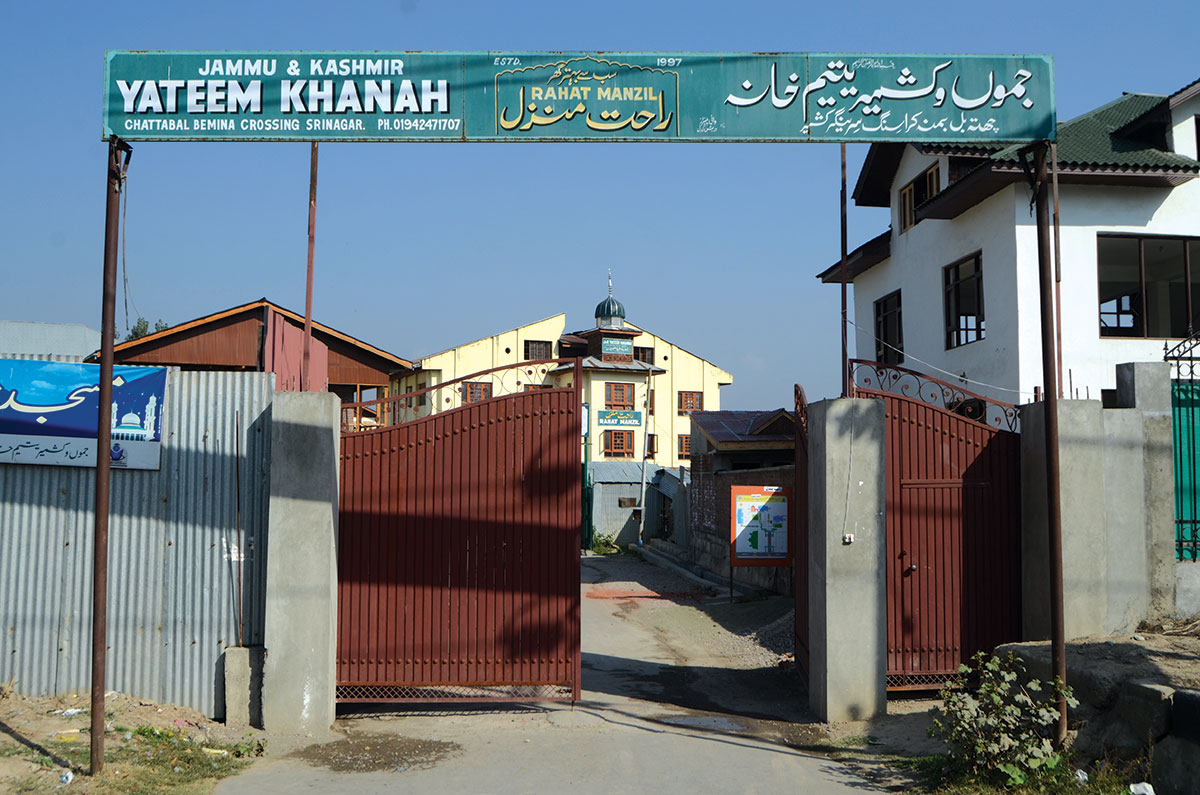

A day later, the civil administration started sealing the properties belonging to Jamaat and its activists. A strong reaction by the public including all the political parties and trade bodies led to exclusions of the schools run by its affiliate, the Falah-e-Aam Trust, mosques and the orphanages. Informally, the private properties of individuals were also permitted for the owners to use against personal bonds.

“Banning this organization will further shrink the space for politics and dialogue and it seems that the government of India is now completely depending on the force as a measure to subjugate the people of the state,” Mehbooba Mufti, the PDP president said, insisting it was “constitutional vandalism”. On more than one occasion, she asserted she had resisted this BJP move as Chief Minister.

National Conference, the arch-rival of Jamaat, said “suppression breeds radicalization”, insisting by banning the party, “the process of reconciliation and rapprochement will impede.” Sajad Lone said the move was “unfair”.

But the ban, third since 1975, pushed Jamaat to the sharp focus of attention. Despite being a huge organization in terms of reach and influence, the party has quite a few milestones in its troubled history. In between 10 dates, lies more than 75 years of the history of a party that believes in Islam as “the way of life” and does not see any de-linkage between faith and politics.

1942: The Genesis

It was a gathering of three school teachers Moulana Saiduddin Tarbali, Ghulam Ahmad Ahrar and Abdul Haq Barak, who met on the banks of a rivulet in Shopian’s Badam Bagh (almond orchard). Jamaat-e-Islami’s official historian Syed Atiqullah Ashiq Kashmiri, in his Tareekh-e-Tehreek-e-Islami Jammu and Kashmir sees this gathering as the first formal Ijtima that laid the foundation of the party in the state of Kashmir in 1944.

Seemingly, the meeting was the desperation to seek answers to the issues of faith and life in Kashmir ravaged by the exploitation of the governing class. Saaduddin was from Srinagar and Ahrar from Shopian and fate brought them together to a middle school where they would teach. The situation was not ordinary: Kashmir was witnessing a sort of a political awakening after more than a century of absolute exploitation by Pathan, Sikh, and Dogra misrule; the political class was exhibiting an influence of Communism and the Qadiani sect, and the matters of faith were literally rationed by the clergy to a mass illiterate society.

The two men had accessed Tarjaman-ul-Quran, a monthly publication by Syed Abul Aala Moudoudi, a Pathankot based Muslim scholar. In his writings, they started finding answers to their quests. A year later in 1945, four ‘neo-convert’ to Jamaat including Qari Saifuddin, attended the first annual all India meeting of the Jamaat in East Punjab. Moudoudi had set Jamaat in August 1941 in Lahore. After their return, they set up Jamaat in Kashmir and Saaduddin was elected as its president, a position he retained till 1984, for around 40 years.

Since most of the founding members were teachers, they started Tableegh, helping Muslims understand Islam better, a process that Srinagar’s Mirwaiz family had launched much earlier. It brought the Jamaat leader in a confrontation with the rulers – initially with the Maharaja Hari Singh’s sarkar, and later with the Sheikh Abdullah and Bakhshi led governments. Saaduddin eventually resigned as a school teacher in 1957 and started working for the party round the clock.

For more than a decade, Jamaat was apolitical. It worked overtime to find takers for, what Kashmiri says, the movement, sort of revival of the faith. Apart from getting involved in social work, its cadres devoted time to educate people, initially in the part-time Darsgah, and later in formal schools. The focus remained on retrieving Islam from the clergy and getting it out of the ritualistic fold that cultural practices and superstition had imposed. The leaders believed improved literacy and access to knowledge would change the situation. Slightly later, they also thought of publishing their own periodical, Azaan, the call for prayers, was launched in 1948. The party was a proud owner of a printing press in 1967.

1953: The Distinction

As the newly found party was busy getting numbers to spread its message, India divided into two sovereigns and Kashmir became the bone of contention. The case went to the United Nations after the ceasefire led to the bisection of erstwhile Kashmir state into Jammu and Kashmir and the Pakistan administered Kashmir. “Till 1952, the Jamaat remained linked with the constitution of Jamaat-e-Islami Hind amid expectations that the Kashmir issue will get solved,” Aashiq Kashmiri notes. “But when the situation turned sensitive and Kashmir was declared to be part of India, Jamaat asked its workers to work separately.”

Post 1952 Delhi agreement, Jamaat constituted a committee to draft its own constitution, which was approved by the party on November 2, 1953. It invoked the dispute over Kashmir to stay separate. Barring the issue of Kashmir that makes the Jamaat in Jammu and Kashmir distinct and different, there is not an iota of difference between the systems and the processes of the Jamaat network across South Asia. Interestingly, Syed Ali Geelani joined Jamaat the same year.

1969: Democracy, Yes

One of the most frequently asked questions is: why Jamaat joined politics. It is a huge debate in academia and politics. “It was only in 1969, that the JIJK (Jamaat-e-Islami Jammu and Kashmir) for the first time decided to enter electoral fray by fielding its candidates for the local level (Panchayati) elections,” scholar Ghulam Qadir Bhat writes in his PhD thesis The Political Identity of the Muslims in the state of Jammu and Kashmir (1947-2008): A Critical Study. “JIJK argued that remaining outside the sphere of the electoral politics was increasingly ineffective. By contesting elections it was thought that elections would provide the best platform to propagate the message of JIJK.”

Ashiq Kashmiri, however, has noted that Shoura (advisory council) had permitted participation in Panchayat polls in 1962, and Jamaat members would contest in such polls being held on non-party basis. “We have never believed in that the faith and politics are delinked,” Kashmiri writes. “If constitutional and democratic means pave way for systemic corrections, Jamaat will utilize it.”

The participation in elections became an issue in 1969 when Plebiscite Front and Congress, the other two non-party contestants, decided to make an issue out of it. This was despite an understanding between the Front and the Jamaat. However, Geelani in his autobiography Wullar Kinaray insists the Jamaat ensured its elected members resign in protest against the Congress government for resorting to unfair means.

But the Shoura permission for electoral participation opened a new sphere of activity for a party that believed Kashmir was a dispute but was willing to swear by the constitution of India. Unnerved by Jamaat popularity, Kashmiri observed that the political class attempted blocking them from getting into the elections and even managed passage of an amended Peoples Representation Act to block the party from entering polls.

Quickly came the Lok Sabha polls in 1971 and Jamaat decided to contest. Geelani has written that Plebiscite Front was planning to contest and it created a crisis for Congress that banned the Front. “Jamaat decided to contest and fill the vacuum and the decision was vital in the given situation,” he has written. The Front, however, supported proxies. Journalist Shamim Ahmad Shameem won with a huge margin and defeated Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammad. Syed Ali Geelani and Hakeem Ghulam Nabi ended as runner-ups as Congress wrested north and south Kashmir.

In his autobiography Wullar Kinary, Geelani has said there was a conspiracy that led to the defeat of Hakeem. A senior Jamaat leader said that Congress had managed somehow luring an Imam from Bijbehara who announced a boycott when almost half of the polling was over and the Jamaat candidate was away overseeing polls in the periphery. Post-results, the party wanted to challenge the outcome in the Supreme Court “but lacked financial resources”.

Geelani’s writings suggest that Jamaat was friendly with Sheikh Abdullah. After the elections were over, Geelani and many other Jamaat leaders had visited Sheikh in 5-Kotla Lane Delhi.

A year later, Jamaat contested the assembly elections even though two of its veterans were not supportive. It won five berths including Khanyar where its candidate Qari Saifuddin signed the nomination papers in jail and did not campaign personally. He was arrested as an alleged law-breaker and he came out of the jail as a lawmaker!

However, this has a counter-narrative. “Syed Mir Qasim, the then Chief Minister of the state, admitted that to frustrate further attempts by any group with support from Abdullah to contest the Congress, they enlisted the service of the JIJK to fill the vacant political space and guaranteed its success in five constituencies,” Banday writes, quoting Balraj Puri. “It was the first time that JIJK received its constitutional recognition and political legitimacy in Kashmir.”

Whatever the truth, Jamaat skipped only the 1980 Lok Sabha elections because it lacked resources to contest. It stopped contesting polls after the militancy broke out.

1975: The First Ban

After being freed from jail and getting encouragement from Pandit Nehru to fly to Islamabad and meet Pakistani leadership in May 1964, the last formal engagement that Sheikh Abdullah had in Srinagar was a Jamaat Ijtima in Mujahid Manzil locality where he heard Geelani and two student leaders. But the relations deteriorated as the two parties emerged political competitors, especially after 1975 accord.

So when Indira Gandhi imposed emergency, Sheikh implemented it to RSS and Jamaat. “As a result of the ban, 125 schools of the JIJK, with over 550 teachers and 25,000 students, were forcibly closed down, being accused of allegedly spreading communal hatred, a charge that JIJK leaders strongly denied,” Yoginder Sikand wrote in his detailed paper The Emergence and Development of the Jamaat-i-Islami of Jammu and Kashmir (1940-I990)

“In addition, the estimated 1000 evening schools of the JIJK, in which some 50,000 girls and boys received education, were also banned. Top JIJK leaders were thrown into jail, in an effort, according to the Jama’at’s official historian, to ‘stop the Jama’at’s message of human awakening and its mission of bringing about a cultural revolution among the Muslims.” Those arrested included the five Jamaat lawmakers!

Party’s official historian says the government sealed four high schools including one exclusively for girls, 41 middle schools including five exclusively for girls, and 34 primary schools.

As the Emergency was lifted in 1977, Jamaat cadres started moving out of the jail to restore their life and the organization. The party eventually “decided to put the administration of its schools under the control of a separate body, formally independent of it. Thus, it set up the Falah-i-Aam Trust to coordinate the functioning of its schools, prepare their syllabi and appoint their teachers.”

The ban brought Jamaat workers closer to the Hindu rightwing, at least, in the jails. Detainees from Jana Sangh were invited to a tea party and it led to increased interactions. In his brief autobiography, Muhimaat-e-Hayat, Qari Saifuddin has mentioned that in Jammu jail, he and the rightwing RSS leaders planted a tree jointly and named it Pream Pouda, the love plant!

1979: Up In Flames

Pakistan situation has been impacting Kashmir throughout. So when dictator Zia-ul-Haq hanged Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Kashmir erupted. The entire anti-Jamaat camp joined hands with each other and decided to unmake the party. Between April 4 and 9, the government was literally on the leave. Even Chief Minister Sheikh Abdullah decided to stay in Jammu till April 9, afternoon when according to Geelani, he smiled at him at the airport and asked: “Do you need any security?”

The agitated mobs, some as big as 50,000 people, shouting slogans against Jamaat moved from village to village and set afire or looted the homes and properties of its activists. Two persons were killed. Aashiq Kashmiri recorded the losses: 1245 homes, 513 grain houses, 22 industrial units, 338 shops, 509 cowsheds, 24 party offices, 651 libraries, 10 mosques, five go-downs, 32 part-time Darsgah’s, 82 cattle, four automobiles were set afire; 466 homes were looted and 70 apple orchards were axed down. The Jamaat literature was thrown in toilets.

The rioting took place in 178 villages across the state and included nine villages which went up in huge conflagrations.

Jamaat delegation visited Delhi and met the Government of India. In Kashmir, police lodged reports and identified the accused. In certain cases, some recoveries of looted material were also made. Knowing well that nobody would be eventually held responsible for the mass rioting because of political involvement, Jamaat withdrew the criminal cases and announced Aam Maafi. In the long run, it triggered, what is now being called, a ‘reverse swing’.

1982: Halting Change

Post emergency, the Jamaat decided to go for youth engagement and set up a student organization, the Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba (IJT). The idea, according to Geelani, was to ensure the presence in all the educational institutions and also see the youth group as a feeding centre to the mother organization. Initially headed by Ashraf Seharie, eventually, Tajamul Islam became its face. Within a few years, it emerged Kashmir history’s biggest youth force.

In 1979, soon after the Iranian revolution, the IJT organized a grand convention in Srinagar’s Goul Bagh, now the home to High Court and the state assembly, which more than 10,000 youth attended. A number of top student leaders from the Muslim world attended it. “In seeking to link up with Islamic students’ movements in the rest of the Muslim world, the Jami’at applied for and was granted membership of the Riyadh-based World Association of Muslim Youth (WAMY) and its associate, the International Islamic Federation of Students’ Organisations (IIFSO) in 1979,” Sikand writes. The next year, Jamaat and IJT jointly organized a grand day-long Seerat Conference in May that was addressed by Imams of the Holy Kaaba and Masjid-e-Nabvi. There was participation from Iran and other Muslim countries as well.

As IJT was planning another conference in August 1980, a reporter asked Tajamul about his ideas on Kashmir and he responded saying he loves the Iranian style revolution. Hell broke loose and police swung into action and started arresting the leaders of Jamaat and IJT.

This led a re-think in Jamaat. “On the working front, Jamaat-e-Islami has two contrarian views – one, that is too much in dawah (preaching) and (maslihat pasand) expedient and other is revolutionary,” Geelani has written. “The former section has taken control over the decision-making in the party and it was this section that succeeded in convincing Jamaat that Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba needs not an independent and autonomous identity and must become a subsidiary section of the Jamaat. It took one year of discussions and finally, they prevailed and in 1982, Jamaat pulled back its staff from the IJT and set up Shouba-ie-Talaba.”

Since both the organizations were operating in the same eco-system, the tensions were visible. There were acrimonious feuds. Tajamul and his team attempted retaining the group but it could not sustain for long. Part of the leadership had gone back to the Shouba-ie-Talaba. Gradually, it disintegrated as the core leadership started raising their families and hunting for jobs.

1987: Challenging Big Brother

Kashmir had changed a lot within years of Sheikh Abdullah’s demise. Maqbool Bhat was hanged. Dr Farooq’s government was pulled down. A bit of rioting also took place and governance issues were never given a priority. Finally, Dr Farooq felt forced to ally with Congress. In between, Jagmohan era triggered its own crisis as he attempted implementing a rightwing agenda and sacked a group of employees who reacted to his decision-making.

All these factors played in the making of Muslim United Front (MUF) in 1987 when Jamaat shook hands with many like-minded and put up a historic show against the NC-Congress alliance. Then, Mirwaiz Molvi Farooq was with the ruling alliance and Abdul Gani Lone, literally alone.

“We never expected to win more than 20 seats but we were sure we will be a responsible opposition in the House,” a senior Jamaat Rukn said. “The mass mobilization created a record of sorts in participation but it did not help as mass rigging took place.” Geelani, however, believed MUF would get any number between 30-35 seats.

The March 23, 1987 election had helped MUF to get a huge chunk of youth back to the mainstream that had either distanced from the electoral politics or was disinterested with all the Jamaat initiatives. Even those not believing in elections were around.

“I remember a group of youth sitting with Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, the de facto brain behind MUF, in Jamaat office and telling him (on the day of results): Sandouk Ki Baat Khatum, Ab Bandouk Ka Zamana Hai,” a Jamaat leader said.

MUF won five berths and ended up as runner up in 31 constituencies. It lost five seats where margins were lesser than the votes rejected. A year later, militancy erupted. On August 30, 1989, all MUF lawmakers excepting Abdul Razak Mir, submitted their resignation. MUF could not sustain for long. It bifurcated and eventually was consumed by the new situation. Syed Shah, one of the four MLAs died in police custody and Mir was later brutally murdered by Ikhwan, a pro-government militia.

1990: The Second Ban

By the time, the MUF’s “losing” candidates were fighting for bails in the courts of law, a lot of water had flown down the Jhelum. Hundreds of young men had crossed the Line of Control (LoC) to get trained in handling arms. Some had even gone deep into Pakistan’s “strategic depth” to pick up the art from the Afghan war veterans.

Initially, the Jamaat leaders mistook it as interventions from the centre to destabilize the state further, some even termed it “terrorism”. Jamaat was the late entrant into militancy. It was a Falah-e-Aam Trust school teacher Master Ahsan Dar who had crossed over twice before launching the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen on September 15, 1989.

In February 1990, a section of Jamaat leaders agreed to own the outfit but it had to wait a month more till Pakistan accepted it, according to Dar’s interview to Rising Kashmir. Gradually, Jamaat members started taking over the group that eventually led to the appointment of Mohammad Yousuf Shah alias Syed Salahuddin, the MUF candidate from Amira Kadal as the Hizb boss after Dar stepped down. By the time Dar left the outfit in late 1992, Hizb had completely changed. Almost every part of its unit has a direct liaison with Hizb. The Hizb-Jamaat combine created a new set of crisis and, in a way, undid much of Jamaat’s work on the ground. Some of the Jamaat leaders crossed over and started working from Muzaffarabad.

Jamaat involvement in militancy accelerated the internecine feuds as a series of actions eventually led to the emergence of Ikhwan cult. This took the militancy to a different level that eventually led to the assembly elections of 1996.

Why did Jamaat jump into the militancy is a question that will get diverse responses from the cadres. Some see it as an outcome of their “insecurity”, some boast it as a “conscious decision” and many think that the militancy “came like a flood and took everything along with.”

It was in this backdrop that Jamaat was banned as a party by Jagmohan. Its schools were sealed, so were its offices. Most of its workers were arrested. While the party emerged powerful on the ground, it also entailed costs that the situation extracted from the party.

1998: Disengaging From The Gun

As Jamaat became the focus of counter-insurgency, triggering mass migrations of its activists, it was the MUF founder Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, who like the new Amir-e-Jamaat decided to get the party out of militancy, formally.

On November 14, 1998, Bhat was flanked by four top leaders – Hakim Ghulam Nabi, Sheikh Ghulam Hassan, and Ghulam Ahmad Ahrar, to announce that the party must be permitted to work constitutionally and democratically.

“The party has lost about 2000 workers in a covert campaign launched by the security forces and the ruling party in last seven years,” Indian Express quoted Bhat saying. “National Conference was also keeping the central government in dark about the ground realities in Kashmir. It wants to completely wipe out the Jamaat-e-Islami as the ruling party considers us a political rival,” Kashmir Times reported.

This, Bhat did without offering any compromise on its political stand on Kashmir. He disowned all the cadres that had joined militancy and this presser became the base for Jamaat to bounce back.

2003: Managing Geelani

Bhat’s truce, however, did not help Jamaat much as internal issues cropped up. The party’s political section was headed by Syed Ali Geelani, an inflexible Jamaat leader. In the wake of 2002 assembly elections, there was a serious crisis in Hurriyat where Geelani accused some of the constituents of fielding proxy candidates and not campaigning boycott the way it had been done in 1996.

As various Hurriyat constituents sought Jamaat’s help, the party invoked the superannuation at 65 years of age on August 20, 2003, and removed Geelani from the “active services” as head of its political bureau. In quick follow up, Geelani on September 7, 2003, split the Hurriyat. On August 7, 2004, Geelani created his own party Tehreek-e-Hurriyat-e-Kashmir that had members from the Jamaat. This eventually pushed him away from Jamaat. Interestingly Jamaat and JKLF are not members of either of the two Hurriyat running parallel to each other.

Geelani might be the most known name of Jamaat but the fact is that he was never permitted to even become the Amir-e-Jamaat. The highest position that he has had at the party was the vice president.

In his autobiography, Geelani has written that when he, as MLA, went with his resignation draft to get it vetted from his president, Hakeem Ghulam Nabi commented: “You would have been the Amir-e-Jamaat had not Kashmir issue been on your nerves.”