The rise of Muslim United Front (MUF) at the peak of a disconnect between Delhi and Srinagar led to unprecedented participation in the 1987 assembly elections. Rigging and misuse of official machinery against its activities apart, the grand alliance had collapsed embracing the forces it intended to fight well before its four lawmakers stopped going to the assembly, writes Masood Hussain

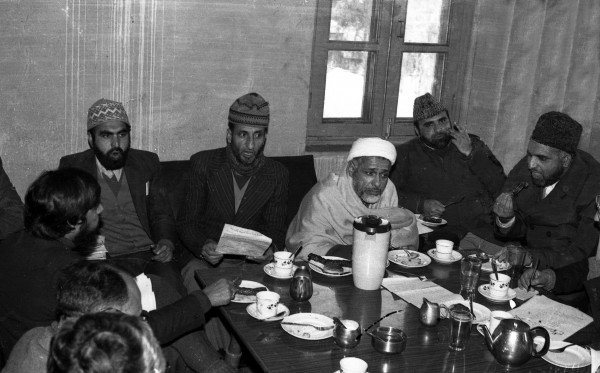

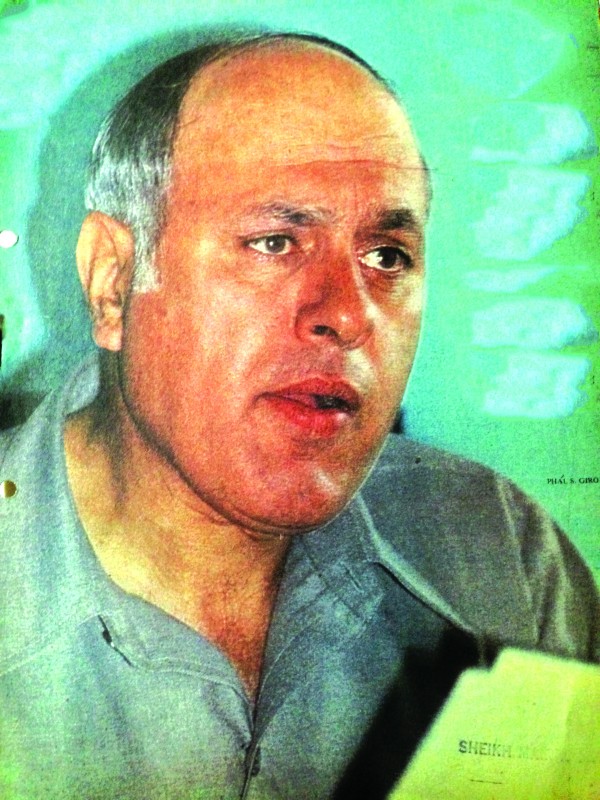

(MUF’s Amirakadal candidate, Mohammad Yusuf Shah addressing an election rally in Srinagar in 1987. Photo in special arrangement with MERAJUDDIN)

When Kashmir converged in Srinagar for a historic send-off to Sheikh Abdullah on September 8, 1982, an era ended. Simultaneously, the new forces within and outside Sheikh’s family, party and the larger Kashmir society, kick-started a new era. In an ideologically divided space, they all were desperate to effect “corrections” in “the legacy”. Kashmir had started changing after 1975 Indira-Abdullah accord but Sheikh’s demise accelerated the pace.

Riding the enormous sympathy wave in 1983 elections to power, Sheikh’s son and successor Dr Farooq Abdullah failed in his balancing act. He picked up battle with Delhi and Kashmir’s entire opposition at the same time. Despite he signed the black warrants against Maqbool Bhat paving way for his Tihar hanging on February 11, 1984; Delhi did topple him on July 14, 1984.

With B K Nehru, her relative unwilling to do the dirty job, Mrs Indira Gandhi picked up Jagmohan for tackling “boyish, inconsistent and erratic” Farooq. Congress purchased 13 NC lawmakers and extended support by its 23-members to help Ghulam Mohammad Shah replace Farooq as Chief Minister. A bloody operation, Delhi purchased men in assembly dragged Speaker Wali Ittoo out as nearly 30 youth were killed in police firing.

Corruption reigned as Chief Minister meekly signed on doted lines every time Delhi wanted. Emergent explosive situation reduced Ghulam Mohammad Shah to Gula Curfew. He dismissed some government employees for “making bombs at home”! These included three teachers in state run Sopore degree college – Abdul Rahim (Geology), Sharief-ud-Din (Arabic) and Abdul Gani Bhat (Persian), on February 27, 1986.

(MUF leaders interacting with media in a news conference in early 1987. Photos in special arrangement with MERAJUDDIN)

In February 1986, a strange situation emerged. A court order banned any kind of entry into Babri Masjid. Finding diminishing political returns, a Congress leader appealed and a new order permitted entry to all. Muslims protested across India. In retaliation to the February 17, 1986 symbolic protests by Jammu Muslims, Hindu right-wingers retaliated. The two communities fought pitched street battles. They even attacked Gujjar Nagar on February 19, set afire a few Kashmiri buses amid rumours that Kashmiri employees were mishandled. Tensions ruled extended cow belt from Chenaini to Kathua. For around five days, till February 25, Srinagar was restive amid isolated instances of selective attacks and loot.

The worst happened on February 20, when a group of unknown Kashmiri women travelling from Jammu stopped at Wanpoh, cried while showing their torn clothes to a crowd. Angry, crowds attacked Kashmiri Pandit homes – 11 houses were set afire, five were looted, attempts were made on 14 temples. The two village communities were already running a dispute over water sharing. Certain sections wanted to spread the crisis but society intervened. When Redwani and Kaimoh mobs reached Danew Kandimarg, locals resisted, and stood guard at Pandit properties. Vernacular newspapers reported Congress leaders were in the rioting frontline. By February 27, a huge delegation of KPs in Delhi was seeking help.

Equations had changed soon after Rajiv succeeded mom Mrs Gandhi in October 1984. Gull Shah had emerged a liability. Shah was summoned to Delhi and flown to Jammu on March 12, 1986 where Jagmohan dismissed him. Governor ruled for six months and got three months of President’s Rule too. This accelerated the “change”.

Kashmir society reacted strangely to the events that unfolded between Jammu and Wanpoh. Almost everywhere, a renewed movement for protecting the “identity” of the “Muslim majority” Kashmir started. Organizations with the same motive mushroomed. Ummat-e-Islami in Islamabad, Majlis-e-Tehfuz-ul-Islam in Baramulla and Pulwama, Muslim Students Federation, Muslim Students Union, Muslim Zone Employees Front, Shia Rabitta Committee, and Unjman-e-Itehad-e-Muslimeen Tral. Even Muslim Employees Front (MEF) was set up.

Jagmohan’s governance reinforced the fears. In 1986 summer when the admission list of professional institutions was out, it triggered youth unrest. The list had 76.54 per cent non-Muslims and 23.46 per cent Muslims. Literally, the colleges locked and moved to roads till Raj Bhawan enquired into its “communal agenda” and managed a face-saving.

Extending certain central ordinances apart, Jagmohan’s high point was the dismissal of nine employees for setting up a ‘communal’ MEF: Professors Ghulam Rasool Bacha, Ashraf Saraf, Ghulam Nabi Bhat and Abdul Karim Kimarni (Baramulla), Abdul Khaliq Sofi, Bashir Ahmad Sofi (Ganderbal), Engineer Ghulam Hassan Mir (Sopore), M Amin Dar (Doabgah) and Abdul Salam Kumhar (Redwani),.

It shocked Kashmir much more than the corpses it had collected on roads that summer. Four youth, two each in Srinagar and Baramulla, were killed soon after Jagmohan’s takeover.

Earlier, Jagmohan’s enforcement of the meat ban on Janam Ashtami had created fears of an enforced faith change. In retaliation, Dr Qazi Nissar butchered two sheep in Lal Chowk Islamabad in August 1986 that made him a star in Kashmir.

At the peak of Farooq-Rajiv closeness, Prof Abdul Gani Bhat, Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, the Jama’at-e-Islami head, Molvi Abbas Ansari and Dr Ghulam Qadir Wani announced the Muslim United Front (MUF) creation in a Srinagar hotel on September 2, 1986. Qazi Nissar, however, was arrested on his way to the venue.

“This alliance was announced in a hotel,” one MUF insider said on the condition of anonymity. “But MUF was actually born in jails and interrogation centres where youth wanted to end this routine (of being jailed).”

On September 3, 1986, Peoples’ Conference’s Abdul Gani Lone was arrested under PSA. Two days later, when Dr Farooq and Mufti Sayeed spoke from the same stage hand-in-hand, police killed Mushtaq Malik in Nowhatta.

After making its constitution public on September 6, 1986 (dedicated to Shafaat Ahmad, a boy killed by police) MUF sponsored an impressive strike to protest a day-long India versus Australia cricket match in Srinagar on September 9. But protests and killings did not stop. The last killing of Jagmohan era took place on September 27, 1986, when BSF beat duty magistrate in Baramulla and killed a protester Manzoor Ahmad.

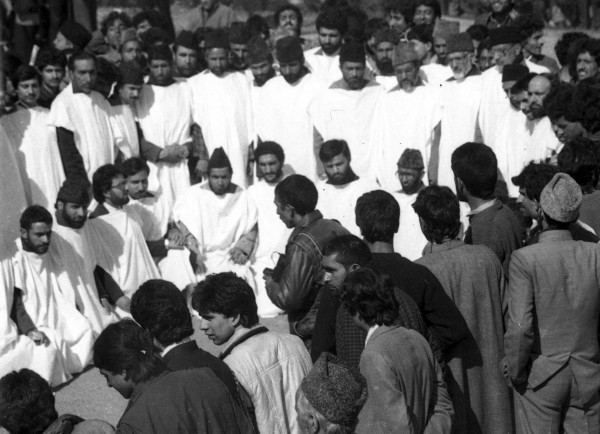

(“Kafan Posh” MUF candidates at an election rally in Iqbal Park in 1987 before March 23 polling day. (Photos in special arrangement with MERAJUDDIN))

Using Jama’at-e-Islami’s skeleton and seeing everything through the prism of faith and not politics, MUF took off with seven demands: release of all political detainees, restoration of judiciary’s dignity, reinstatement of dismissed employees, respect for the basic human rights, rollback of Jagmohan’s all ordinances, corrections in the wrong demographic projections and due representation to the Muslims in opportunities in education and jobs.

Interestingly, this was a rare Jama’at initiative lacking Syed Ali Geelani’s involvement. “In March 1985, I was arrested for 20 months, Geelani writes in his book Wullar Kinaray. “By the time I was out (of jail), MUF was born. I have no contribution in its constitution.”

By then NC-Congress accord had led Dr Farooq to take over as Chief Minister on November 7, 1986. An “unwritten accord”, Jagmohan dubs it “a mere declaration to work together and form a coalition” government.

“The Rajiv-Farooq Accord (November 1986) was another reflex of spurious democracy and the habit of nursing illusions,” Jagmohan wrote in My Frozen Turbulences in Kashmir. “The accord might have yielded positive results if it had been inspired by reformative zeal and constructive approach. But both parties joined hands merely to serve their selfish ends. In practice, the accord only resulted in enlarging the circle of predatory and insensitive oligarchy.”

Farooq set free some political detainees to convey his concern. But the situation had changed. On November 17, 1986, MUF mobilized nearly one lakh Yehan Kya Challayga – Nizam-e-Mustafa chanting people to Srinagar’s Iqbal Park to have an emotional display of anger and hate and unnerve NC. By November, Rajiv flew to the same venue to announce Rs 1000 crore package.

Initially, a section in MUF was keen that the alliance should stay away from polls. Since Jama’at had already announced its participation, constituents decided to go ahead. Even unsupportive of elections, mostly non-voters opted to contribute to “change”.

(The MUF Forum: (L to R) Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, Qazi Nisar, Maulana Abbas Ansari and Syed Ali Geelani. (Photos in special arrangement with MERAJUDDIN))

In the new political formation, Jama’at was the “big brother” with some kind of political experience. The rest had sentiment and emotion. As the platform emerged big, the entire political spectrum opposed to NC and Congress threw hats in the ring. Peoples’ Conference and Awami National Conference (ANC) exhibited desperation to get in.

On January 7, 1987, shoppers and retailers in Maisuma were shocked to see Gull Shah, flanked by erstwhile ministers Hissamuddin Banday and Abdul Rashid Shah being driven in a Maruti car to Jama’at office. It is not known if he came uninvited. By the time he entered the office, Ghulam Mohammad Safi, was presiding over a MUF meeting that also had Abdul Gani Lone in participation.

Lone did not shake hands with Shah. Lawyer Sheikh M Ashraf reacted saying some people here have blood on their hands. Soon after, an angry Lone and Ashraf Saraf, came out of the meeting. Lone was angry. As tensions increased, Shah left.

“Two factors led to failure in having a poll arrangement with Shah,” MUF Convener Molvi Abbas Ansari told me in 1988. “He was seeking mandate for Amira Kadal, Nigeen, Ganderbal and Zadibal and permission to tie-up with right-wingers in Jammu.”

Qazi Nissar supported Shah’s entry into MUF but was shocked when it failed. Then he promised Shah two seats (Noorabad and Kothar) from Ummat-e-Islami quota for his party. No political entity, Shah decided against contesting polls. His wife was under pressure from her mother to keep him in check. Even his 12 “ministers” deserted him. Shah was seen with MUF leaders in Iqbal Park on March 4, 1987, when Kashmir had come to see MUF’s 42-Kafan Posh (dressed in funeral shrouds) candidates.

Unlike Shah, Lone was an influential party. Keen to be part of MUF, Lone hated the idea of Shah. Ansari told me that Lone initially wanted the alliance to be a United Front and not MUF. Then seat adjustment started. Ghulam Mohammad Bhat told me in late 1987, after his release, that Lone was offered two seats each in Baramulla and Kupwara districts. “But he insisted on Rafiabad which we disagreed to and the talks failed,” Bhat said.

Lone, however, complained of a raw deal. “I was formally inducted and administrated oath as a member on January 6, 1987,” Lone told in an interview later. “On January 13, they backed out but said seat-sharing was still a possibility. As negotiations started, I surrendered Langate first and then Rafiabad as well but the arrangement could not take shape.”

“Jama’at was feeling insecure as they thought their hegemony would be neutralized if politicians like Lone and Shah would get in,” a MUF insider of that era said. “They first invoked Islam and then used them against each other to keep both of them away.”

But it failed to prevent the tensions its allies in MUF like Ummat-e-Islami created. Qazi wanted Ghulam Hassan Mir and Hakim Yasin in MUF. In early 1988, he told me, “the fact is that MUF leaders wanted the duo”. It did not happen. But that did not prevent Qazi from terming the duo Ummat-e-Islami’s allies. He campaigned for them against MUF’s official candidates!

Jama’at failed to prevent violation of MUF’s moral code of conduct. Top leaders were not to field their relatives. Its Convener fielded Mustafa Ansari, his brother, from Pattan. Qazi fielded Mohammad Abdullah Sheikh, his father-in-law, from Kokernag. He later claimed the choice was forced upon him by Jamiat-e-Ahlihadees.

Of the 40 seats MUF contested, 18 were given to Jama’at, eight to Ummat-e-Islami, Tehfuz-e-Islami Pulwama got five, Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen got four berths, Shia Rabita Committee got two, as Tehfuz-e-Islami Sopore and Baramulla and Hussaini Medical Trust got one candidate each. By and large, it was a crowd-funded initiative but Jama’at had a proper finances cell that Mushtaq Jeelani managed.

Build-up pressurized a beleaguered Farooq. Since May 20, 1983, he had a running alliance with Awami Action Committee, the Double Farooq Accord. He had asked Molvi Farooq to announce its continuation. On February 20, when Molvi wanted to make a formal announcement in Jamia Masjid there was a commotion. Wires of Jamia’s Public Addressing System were cut and a situation was created forcing Molvi leave the mosque without offering Friday prayers. Later, Dr Farooq had to announce it from Mujahid Manzil on February 22.

It was MUF all around. To counter MUF’s major March 4, rally, shocked Farooq. He flew Rajiv to Srinagar’s Sher-e-Kashmir Park on March 8.

“With the birth of the MUF it quickly became clear that the NC-Congress alliance was going to be given a run for its money,” journalist Tavleen Singh wrote in her Kashmir – A Tragedy of Errors. “Farooq panicked. This is the most likely explanation for his over-reaction.”

Administration played a key role in helping Farooq retain power. DIG Ali M Wattali, Divisional Commissioner Hamidullah Khan Banhali, Deputy Commissioner Srinagar Ghulam Qadir Pardesi and various Returning Officers rarely slept for a month.

“The news reports appearing during the week prior to the 23 March polling read like a police bulletin,” Aditya Sinha, recorded in Dr Farooq Abdullah: Kashmir’s Prodigal Son. “Violent clashes took place every day.”

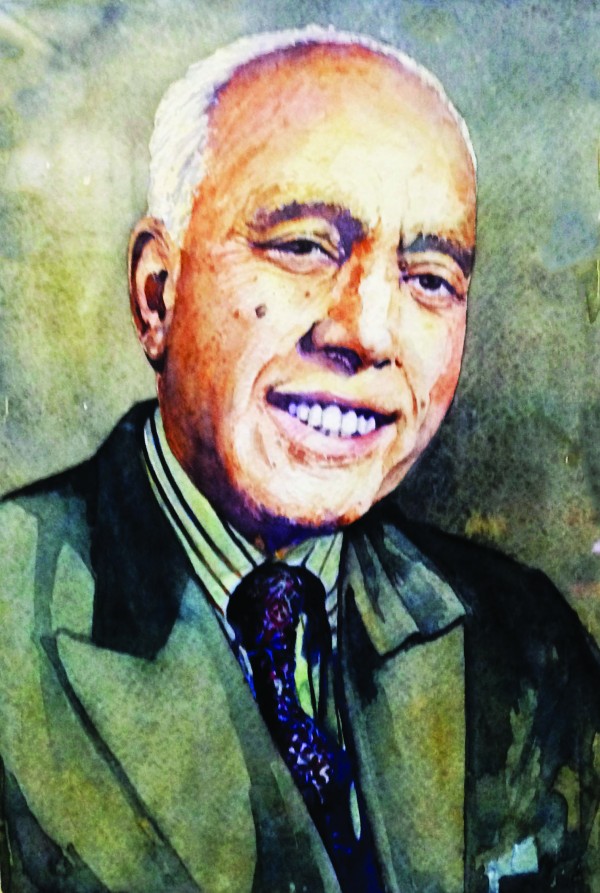

(Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, a portrait by artist Masood Hussain.)

March 23, 1987, proved democracy’s big day. Of Kashmir’s 1921179 electors, 1519761 turned out to vote meaning 79.10 per cent participation, the highest ever. In the evening, when MUF leaders interacted with media, the simpletons said 96 booths were captured. They always talked of rigging but lacked even the idea of it.

The counting proved a different innovation. “The manner in which the state assembly election of March 23, 1987, was conducted caused grave misgivings about their fairness,” Jagmohan recorded. “In some constituencies, counting was suspended and the margin of victory for the NC candidates turned out to be smaller than the votes rejected.”

The margins of victory in Bijbehara was 100, in Wachi 122, and in Shopian 336, while in these constituencies the number of votes declared invalid was 1172, 1703 and 1122, respectively. “These elections, unfortunately, were followed by the arrest of a number of top-ranking leaders of the MUF,” Jagmohan wrote.

“The rigging was blatant,” wrote Tavleen Singh. “Some journalists sympathetic to him (Jagmoahn) even at the worst of times, were to say afterwards that he had told them privately that he was appalled by what he saw being done but had been ordered by Delhi to keep out.”

“The plan appears to have had the concurrence of Delhi and most Kashmiris still remember, how, once the counting started and it began to look like the MUF would win at least 10 seats in the valley, Farooq’s reaction was to immediately fly down to Delhi,” explains Tavleen. “He seems to have returned with a ‘go-ahead’ to do whatever was required and then the government machinery, which in any case had been working openly in favour for the alliance (2 weeks before the polling day at least 600 MUF workers were arrested), was now geared up to play an even more active role.”

India Today’s Inderjit Bhadhwar was perhaps one of the few journalists who retained objectivity. “That it (J&K) was the only state where details of the poll results remained unannounced almost a week after polling ended, gave credence to widespread opposition charges that there was rigging and electoral bungling,” Badhwar reported. “The reason for curfew in key areas was a growing belief among people that the election was manipulated in several areas in favour of the alliance, and people were ready to take to the streets.”

Badhwar credited MUF for bringing out “lakhs of people” who “entered politics for the first time” to confront the “old-line party machine which brings out the vote for NC”. He reported recovery of pre-stamped ballot books for NC (bearing the serial numbers 024864-024898) from Pattan and (numbers 037201-037225) from Idgah, Handwara and Cahdoora.

On March 24, Dr Farooq won from Ganderbal with 22000 votes within three hours of counting 39000-plus votes. But seats having MUF domination took time. “Results from the all-important Anantnag (Islamabad) district were held up for the next two-and-a-half days,” Badhwar reported from the “armed camp” like a counting station surrounded by hundreds of cops. “At the Bij Behara counting room, the polling officers simply stopped counting when a MUF candidate established an early lead. At the Dooru station, the presiding officer declared an NC candidate elected as soon as he took a 300-vote lead even though one ballot box with 1,100 votes had still to be counted.”

Pulwama was declared without counting the key Tahab belt. Shopian was counted for many days till MUF lost by 336 votes. Even Sopore took three days.

Eventually, NC filled 39 assembly berths; Congress 24, BJP 2, MUF 4 and the rest were independents. Despite all this, MUF polled huge. It took 470580 votes making 30.96 per cent of the popular vote. Lone’s Peoples’ Conference did not bag a seat but polled 93949 votes. Had they been together, it would have narrowed the differences further as NC polled 713232 votes making 46.93 per cent of the total Kashmir turnout.

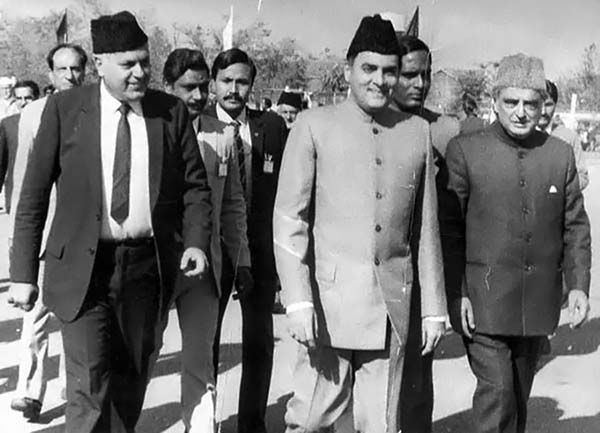

(Post-March 23, 1987 elections, Dr Farooq with his cabinet after taking an oath of office and secrecy. (Photos in special arrangement with MERAJUDDIN))

But why was Farooq so insecure. “There was never any serious chance that the Congress-NC alliance could be defeated but he seems to have decided to make victory doubly sure,” Tavleen Singh recorded.

“Several disinterested observers believe that MUF candidates could have obtained twice the number of these seats had the Government played a more neutral role,” Badhwar reported. “According to top level intelligence estimates done on election eve, MUF was expected to bag at least 10 seats including three in the Srinagar district. Peoples’ Conference (PC), led by the charismatic Abdul Ghani Lone, was expected to do well in Bandipora, Sangrama, Handwara, and Kupwara.”

Terming the election as “the rape of ballot box”, Geelani in his Wullar Kinaray gives a slightly inflated figure of expectations. “Had the exercise been fair, MUF would have won 30 to 35 seats,” Geelani has written. “This number would have helped us to challenge the accession on the floor of the house, though inconsequential, but would have been a Moua’sir Ikdaam (appropriate steps). Rest we had no other objective.”

“I myself did not know how the MUF voice reached the length and breadth of Kashmir like the fresh morning breeze,” MUF Convener Ansari had told me in a 1988 interview. “Given the support, I believed that MUF would win 15 seats.”

Dr Farooq has told his biographer Aditya Sinha that “he himself did no rig” but “heard that some people indulged in the rigging.” Sinha writes: “Sources close to Farooq at the time have since admitted that, for instance, in Amirakadal, the election was rigged by the Returning Officer, who was after rewarded with the chairmanship of a local bank by the winning candidate, Ghulam Mohiuddin Shah.”

“Did he rig the election, I asked,” Tavleen wrote in her book about his interview with Farooq, much later. “His chin quivered and he looked away before saying: ‘No’.”

The rigged elections were the beginning of the end. “When I next went to Kashmir some months afterwards nearly everyone I met said that most of the youths who had acted as election agents and workers for the MUF candidates were now determined to fight for their rights differently,” Tavleen wrote. “They had no choice but to pick up the gun was the message I was given.”

The first post-election crisis for MUF was whether or not to send its four lawmakers – two each from Jama’at and Ummat-e-Islami – to assembly. In newspapers, it looked as if Qazi and a few constituents were against the idea of sending them in. There was such an opinion, even Geelani admits. “A meeting took place at Ghulam Nabi Sumji’s house where Qazi Nisar’s decision prevailed and I was nominated the legislative party leader,” he explains further in Wullar Kinaray. Interestingly, Geelani says that “he had opposed the idea of contesting polls but his party thrust the decision on him”.

But what happened to MUF?

Almost on the day of counting, police raided Jama’at’s Maisuma office and arrested Ghulam Mohammad Bhat, Prof Abdul Gani Bhat, Dr Ghulam Qadir Wani, Mohammad Yousuf Shah and Sheikh M Ashraf.

Those not arrested met and analyzed. “Anti-India sentiment in Kashmir is going to explode,” Abbas Ansari told media on March 27, 1987. “We are not in a position to stop it.” The day the first meeting of the assembly was called Lone said, “Kashmiri youth are being pushed to extremism”. April 4, 1987 was the impressive day long strike against rigging.

Immediately MUF started offering voluntary arrests in protest. Every Friday post-prayers, in every district, MUF would make a symbolic protest and offer arrests. It continued for four weeks and when no arrest was offered in Islamabad, it was stopped.

The restive youth, however, was unforgiving. When Dr Abdullah and Molvi Farooq assembled for Eid prayers in Eidgah, a group of youth beat them. Neither of the two could offer prayers and barely managed to reach home. The youth were actually reacting against the Meerut riots.

Qazi was the top leader left untouched. He hired the services of a “political go-between” and managed a meeting at the residence of Muzaffar Hussain Baig. Mohiuddin Aazim who was part of that meeting told me on record in 1988 that those invited included Sonaullah Dar, Ghulam Hassan Mir, Hakim Yasin, Qazi Nissar and Dilawar Mir. “In order to make MUF a broad alliance, they made two suggestions,” Aazim told me, “One that the slogans of Nizam-e-Mustafa should stop because it was impractical and second Delhi can only permit (MUF) access to power if she is convinced that the alliance would not challenge accession.”

Aazim told me that he reacted to the accession issue that eventually led them “not to invite” him in the next meeting. “They also drafted a six-page note on the MUF which I had no access to,” he said.

Soon after, Shah and Lone returned to an expanded MUF. On August 20, 1987, when Ghulam Mohammad Bhat was set free after five-and-half months, MUF was trying to display its power in Iqbal Park with Geelani, Lone, Shah, Qazir Nissar and Ansari on the stage. Some youth threatened them with death in case of “treason” and they set afire the tri-colour, starting a new spate of arrests.

While Jama’at supported the idea of making MUF all-inclusive, it gradually found being elbowed out. After expansion, Jama’at’s position in MUF’s administrative committee reduced from four to one member and in the advisory committee, it could retain only four berths in 35. The chocked organization gradually lost interest.

An encouraged Farooq’s frequent statements that he will “send them (MUF) to Pakistan,” and give all their (Falah-e-Aam Trust’s) “schools to Muslim Auqaf Trust (MAT)” had added new insecurity to Jama’at.

(Dr Farooq Abdullah)

Soon, the new MUF started discrediting its lawmakers. When the MLAs were part of an official visit to Goa, MUF constituents, Awami National Conference and Ummat-e-Islami, issued them “show cause” notices which was plain mud-slinging. Even Geelani was belittled for flying with Dr Farooq in an official chopper for funeral prayers to Sofi Mohammad Akbar in Sopore. It was later found that Ummat-e-Islami lawmakers had checkmated their boss!

By the time, Prof Gani, Dr Wani and others were freed on January 1, 1988; MUF had ceased to exist, literally. On June 11, 1988, Ansari, at the peak of power agitation in Srinagar, expelled Jama’at and all its four lawmakers from MUF. Three days later, Prof Bhat and Dr Wani reacted and termed it anti-constitution. It buried the parallel factions forever.

Three of its four lawmakers resigned from assembly on August 30, 1989, after feeling convinced that militancy was real and not a “Congress conspiracy”. The fourth was assassinated as a serving MLA.