For almost 66 years, unruly Pathan warlords ruled Kashmir with a hunter in hand and eye on their subjects’ purses. There are detailed historical texts explaining the misrule but the plunder was preserved for posterity in its crudest form by the folk culture, Rouf Ahmad Mir writes

Right from the Mughal annexation of Kashmir in 1586 to the end of an autocratic power structure in 1947, almost all non-Kashmiri governing elite attempted to seek public legitimacy, not through an apparatus of goodwill, love and affection. They applied more harshly the apparatus of power, authority and coercion to seek peoples’ legitimacy for the survival and accomplishment of their political objectives. Though Mughals attempted to win the hearts of Kashmiri through a number of public reforms still they could not stem out the seeds of alienation that culminated as a result of unending conflict between the region and the Mughal realm.

Seeking Legitimacy

With the establishment of Afghan rule in Kashmir in 1753, the roots of alienation got further strengthened as the Afghans applied the tool of authority and coercion with redoubled scale to muzzle the public sentiment and seek legitimacy for their survival. The conflict between Afghan authority and regional forces assumed a diabolic dimension, every time the Afghan subedhars finding the central authority week, revolted against them to declare themselves as sovereign rulers. This resulted in an unending clime of mistrust, disbelief, insecurity, anarchy and inter-strifes. The worst-hit causality amid such a chaotic situation was none else than the common man or majority peasant and urban artisans.

The contemporary chroniclers no doubt, documented to some extent, the anti-people behaviour of Afghan officialdom but to be on a safer side, they attributed almost every ugly occurrence to metaphysical forces. However, the true picture of Kashmiri society gets reflected in vernacular literature, particularly in the folk literature of Kashmir. Since folk composition stands free of individual ownership, as such, the composers of folk literature regardless of falling prey to official brutality documented the pain of public and licentious behaviour of Afghan nobility and officialdom in an unvarnished expression. This, to great extent, may be taken as a true reflection of peoples’ perspective which would have otherwise remained unnoticed or undocumented in the conventional literary-historical sources.

The entire period of Afghan rule (1753-1819) in Kashmir can be characterized as an unending conflict between Afghan state and regional forces, declaration of sovereign status even by Afghan governors against their own masters, intermittent attempts of loot and arson by local chieftains, particularly, by Bombas, Khakhas and Gujjars of Poonch, periodical sectarian clashes, mostly between Shias and Sunnis, recurring causation of natural calamities like floods, famines, earthquakes and the pathetic tale of misgovernance and acute exploitation of Afghan officialdom.

Rich Folk Literature

Hardly any literary folk genre, may it be, folk plays (Bhand Pather), folk sayings, proverbs, allusions, folk songs and folk stories, where one do not come across ugly reflections of Afghan governance in Kashmir.

For example, in Bhand Pathers, the traditional theatre of Kashmir, a reader stands acquainted with too full length plays entitled Raza Patheer and Darze Pather wherein the focus is laid on the scandalous, luxurious and sensuous tastes of Afghan aristocracy. The two beautiful lady attendants known as Derzas symbolize the involvement and lust of the Afghan governing elite in sensuous pursuits. The lack of administrative acumen and the absence of public welfare concern is shown in the folk dramas by various theatrical skills and scenes.

Since corruption was rampant during Afghan governance in Kashmir, the Afghan governors deputed to Kashmir and their subedhars and naib-subedhars always busied themselves in fleecing poor peasantry in the name of Rasum and other allied revenue taxes. The heavy exactions forced peasantry either to migrate to Indian plains or desert the land. This state of affairs is depicted in Raza Pather through one of the characters known as Sagwan.

In one of the scenes of the Pather, Sagwan – an official, demands honey from a Kral (potter). The Kral instead of bringing honey carries a pot full of mud and offers it to Sagwan as a bribe. It not only refers to immense hatred of menial village professions against corrupt officials but it is also suggestive of a collective protest against the established system based exclusively on corrupt practice. These corrupt officials used to live in spacious houses and spent their nights in “colourful parties”. An extract from Raza Pather:

Sagwan: (while slapping Kral) Have you brought honey?

Potter: (bending his head a bit down) Here, it is sir, it is in this basket.

Sagwan: Have you brought fowl?

Potter: I have got honey as well as fowl (unloading the basket, potter takes out a mouthful of mud and starts eating it).

Sagwan: Where is honey?

Potter: (referring to mud) This is honey would you like to taste it? Here it is (pointing to mud)

Two Key Characters

The undercurrent disdain against the corrupt system which was in receipt of Afghan official approval stands exposed before the spectators. Through two main characters Navid (barber) and Kral, the Raza Pather takes stock of various categories of corrupt state officials and make them subjects of tremendous public ridicule. The Pather also highlights the moral laxity prevalent under the Afghan feudal structure in Kashmir society. The play unmasks the scandalous lifestyle of the political elite and landed aristocracy.

The “plough scene” in the Pather attains the highest tone of political protest and social disapproval to the barricades created by government officials, which sought to deter the suffering peasants to address their genuine grievances to the Afghan governor. The symbolic exhibition of the Albani, the plough with the petition tagged at the top, and holding, the plough high with a petition paper, stands for the silent protest of the peasantry against the highhandedness of revenue officials.

Ijaradars of Yore

Though there is no record of any organized protest by peasantry even against the worst type of exploitation at the hands of Afghan Ijaradars and Jagirdars in the historical contemporary texts but the chronicles abound in details about the illegal exactions which often crippled the very existence of poor peasantry. In Bagh-i-Sulaiman, Sadullah Shahadi has stated:

“The Ijaradari system assumed alarming proportions under the Afghans. In fact, the first Afghan governor, Abdullah Khan Ishaq, received whole Kashmir in Ijahara against a huge amount of twenty-four lakh rupees, which was to be realized on account of the land revenue and other taxes. Ijardari system envisaged the ruin of the peasantry and led to the declining trend in population. The mustajir under the existing terms of the contract was usually required to deliver a fixed sum of revenue within a stipulated period of time, no matter how he realized.”

Another Drama

Yet another Kashmiri traditional folk drama Derza Pather symbolically stands for rapacious Afghan governing culture. Dard Raja, who represents the kind of Afghan governing elite, is always shown in the company of beautiful Kashmiri courtesans known in vernacular as Derzas. The Afghan governor’s presence in the company of two beautiful Derzas and their sensual gestures towards the Raja is suggestive of the scandalous and sensuous behaviour patterns of the Afghan ruling aristocracy. The repeated intervention of the Maskharas (jesters) is a conscious attempt to make the Raja feel that the public, though lacking accessibility to the corridors of power, knows of his luxurious and scandalous lifestyle.

One of the most striking scenes of Derza Pather is when Maskhara asks Raja that we can acknowledge you as our true Raja if you grant back the power of expression to otherwise dumb driven Kashmiri. This indicates how sensitive the Kashmiri people were about their political and cultural identity.

The language used in the play Derze Pather is pure Persian, the official language of Afghans in Kashmir. In tune with Mughal fashion, Afghans also used Persian as an official language. The imposition of alien language further distanced Kashmiri from Afghan and the sense of language causality at the hands of foreign rulers was so deep and painful in Kashmir collective psyche that they compiled abusive expressions against Afghans in vernacular.

The disdain that Kashmiris developed against Afghans for the Kashmiri language’s sad plight is evidenced from this scene:

Dard: Do you want to express in Punjabi?

Maskhara: Yes, of course, I can speak Punjabi, Arabic, Hindi, Ladakhi, but not Persian.

Raja: Rohilla – Where have you come from?

Rohilla: I have come from Kabul

Raja: Well done, do you know Punjabi?

Rohilla: I know the Persian language, Punjabi language, Pashtu language, but I do not know the Kashmiri language.

In the entire plot of the play, the Afghan barbarity is so vividly depicted that offers ample chance for the audience to demonstrate their reaction and response. The play stands as a model for sorrowful poetic expression:

I inquired of the gardener the cause of the destruction of the garden,

Drawing a deep sigh he replied, it is the Afghan who did it.

The Historic Context

The folk narrative is substantiated by historical texts as well. PNK Bamzai sums up the bungling of the nobility:

“Rude was the shock that Kashmiris got when they witnessed the first acts of barbarity at the hands of their new master…Abdullah Khan Isqk Aqasi, let loose a reign of terror as soon as he entered the valley. Accustomed to looting, murdering the subjected people, his soldiers set themselves to amassing riches by the foulest means possible. The well to do merchants and noblemen of all communities were assembled together in the palace and ordered to surrender all their wealth in pain of death. Those who had its audacity to complain or resist were quickly dispatched with the sword and in many cases, their families suffered the same fate”.

The Tax Systems

With the inclusion of Kashmir in the Mughal realm, the governors deputed by the Mughal court in order to appease their imperial masters at Agra, designed the valleys tax structure in such a way, which aimed to cripple the very existence of poor Kashmiris, particularly, rural peasantry. Their immediate successor in Kashmir – the Afghans continued the harsh revenue mechanism but further widened its net to cover other shades of Kashmiri social organizations.

How these intolerable loads of heavy exactions brought havoc to the Kashmir agriculture sector has equally been documented by contemporary historical texts and folklore as well. The author of Gulshai-i-Dastur, provides the information of taxes and cesses levied from agricultural class revenue functionaries:

“As under the Afghan, each village yielding minimum revenue of a Kharwar of paddy paid besides normal taxes, one trak annually towards the revenue functionaries. Similarly, on every one rupee of mehsul, each village was required to pay two annas annually to the Kardar”

Yet another contemporary historian Birbal Kachru states on the same subject as under: “Likewise, every such village which yielded revenue of four hundred Kharwars of paddy, was burdened with a cess payable to the revenue functionaries at the rate of sixty-two dams equivalent to the cost of two goats”.

During the successive Afghan governors and subedhars, volumes of the said cesses increased further, Azim Khan and Karim Khan who assumed the reigns of government under Afghans in Kashmir in quick succession exorbitantly charged ten to twenty rupees plus five to ten sheep, two to four traks of oil, four traks of salt and five to ten kharwas of rice annually from the peasants of each village.

The Other Taxes

Following the footsteps of the Afghan governing elite, the local Zamindars equally claimed a number of petty perquisites. They levied poll tax called dastar-shumeri, (turban tax) besides damdari tax (tax on bird catchers) Sar-i-darakh (tax on orchards), zar-i-duddi (smoke or hearth tax) telli-chirag (fuel tax) etc. Peshkar, as the chief officer in charge of revenue collection at the Pargana level, did not lag behind in claiming presents and gifts from the villagers on the occasion of the receipt of seeds from the government. The peasantry also paid Zar-i-Niyaz (presentation tax) to higher-up officials through the village Muqdam.

In addition to the peasantry, several other sections of the society were brought in the text net to drain even the meagre income of different categories. Baj and Nazrana were levied with great vigour. Besides, Zar-i-Nikah (marriage tax), several other taxes like, Zar-i-Hasrat (tax on shops), Zar-i-Bayutat (tax on houses) etc.

During Amir Khan and Karimdad Khan, the exactions reached to its height. Such was a deep imprint on the folk psyche of these exactions that Kashmiri coined an abusive folk expression like Chetly Kareem (meaning extortion by Kareen) for Kareemdad Khan and a folk allusion Azad Khanun dabdaba, which still stands in circulation in Kashmir vernacular.

The metaphoric expression in vernacular stands for unjustified and unprecedented state exactions. The folk expression stands attested by the contemporary historical narrative as well.

A Heartless Father Son

“Haji Karimdad Khan was rather heartless and killed alike Hindus and Muslims on provocation. His exactions through Aslam Harkaram, his unscrupulous tax collection, exceeded even those of the notorious Itiqad Khan, the Mughal subehdhar and compelled many to leave the country. Certain Pandits who were concerned in a conspiracy with the Bombas against Karimdad were exposed to suffocation by smoke. For librating them, Karimdad realized a large indemnity called Zar-i-dad. He also levied an anna per rupee on the price of shawls from the weavers”.

The reigns of Afghan governance in Kashmir passed on to Azad Khan, after the death of his father Karimdad Khan. For his ferociousness, bad temper and arrogance there came into circulation in folk medium, an expression known as Azad Khanun Dabdabe. Like many of his predecessors he also declared his independence but was forced to pay three lakhs of rupees by Timur Shah, the Afghan king, as a tribute, which of course, Azad extorted from his wretched subjects. In an oral tradition, there runs a story of his arrogance and ferociousness as under.

It is said that once when his wife was about to deliver a baby, Azad Khan told her, if she gives birth to a male baby, you would be put in high esteem in the royal household and if a female baby is born to you, both you and your baby shall be assassinated. The folk tradition says that his wife gave birth to a female baby and hearing the news, Azad Khan is said to have sliced into pieces her wife and her newborn baby. The folk belief further adds that the news received wider publicity in civil circles that frustrated arrogant Azad Khan.

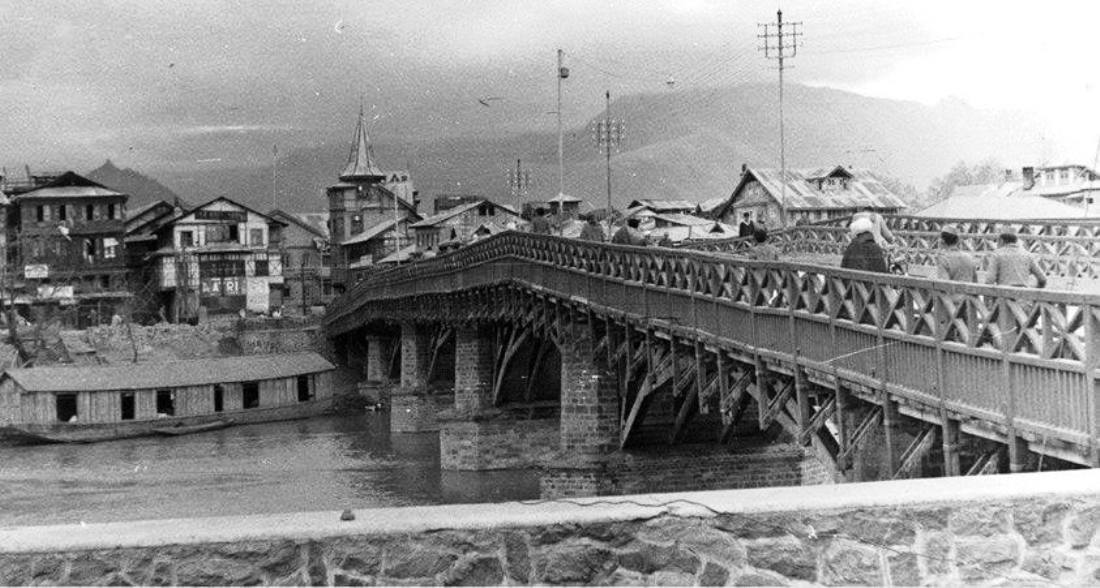

After enquiry, when the Afghan governor came to know that the news had been transmitted by one royal household servant to the general public at Zaina Kadal gossip centre, the man was butchered and all the structures standing on both the sides of Zaina Kadal bridge over river Jehlum were reduced to rubbles at the orders of Azad Khan.

Azam Khan

Azam Khan had been hateful for his acts of cruelty from the very start of his career. After defeating Sikh troops, he became more arrogant and ruthless. He let loose a reign of terror, confiscated jagirs of some Hindu zamindars, many Muslims also suffered with the Pandits. Azam Khan also discharged all the Kashmiri soldiers from the army because he distrusted their loyalty.

Sensing the end of Afghan rule in Kashmir, Azam Khan employed all tactics to exact as much as he could from different sections of Kashmiri society, which among others include, zamindars, jagirdars, peshkars, sahibkars, peasantry, artisans, prostitutes and other professionals there hardly remained any category of professionals and skilled workers who remained untouched from his cruelty. This is evidenced by the fact that when he was about to leave Kashmir for Kabul, he handed over one crore rupee to Sahaz Ram Dhar to carry it to Kabul. This huge amount was realized in a quick hurry implying all legal and illegal ways. It is for this catching hold of every productive object in the shape of kind and cash, the multitude of Kashmiri folk coined as a folk expression, which runs as Azeem Khanun Chetty.

In yet another Kashmiri folk genre known as Pretch (riddle) Kashmiri have documented the metaphoric reflection of Afghan collective personality by reproducing multiple episodes that occurred during the Afghan rule in Kashmir.

Folk Culture

In folk culture, nicknames, abuses, rumours and slogans are of great significance as these oral sources offer penetrating insights into the character of officialdom, response of the general public and the collective behaviour pattern and mindset of the particular society.

In the following Kashmiri riddles the reflection of peoples’ response towards Afghan governing culture stands reflected in a true colour:

The crux of this riddle refers to lighting and thunder by Juma Khan, the folk expression refers to Juma Khan Alkozi the Afghan governor of Kashmir who ruled over Kashmir for four years the absurd expression of lighting and thunder in the riddle indirectly refers to arrogance and ruthlessness of Juma Khan.

The Afghan feminine beauty has assumed a predominant thematic shade in Kashmir folk poetry. In different wanun and Roaf songs of Kashmiri language, the expression Pathani stands for un-matching feminine beauty and charm. The beautiful Kashmir bride is often compared with bewitching Afghani feminine looks.

You are just like a Bakir Khani (delicate bread in layers) at Kashmir baker-shops; come on Pathani, your hair is styled so delicately.

You will be bathed from pure spring water, do you listen to the roaring sound of water, Pathani?

(Author has a doctorate in history and is a teacher. This essay was excerpted from his MPhil thesis.)