British traveller and East India Company official, George Forster (died 1792) is the first Englishman who journeyed from India through Central Asia to Russia. In the spring of 1783, at the peak of 67-year long Afghan rule, he was in Kashmir. Read what he recorded in his book that was published almost a decade after his death

Veere Naug was the first village we halted at, within the valley, where our party was strictly examined; but, from the respect shewn by all classes of people to Zulphucar Khan, we were permitted to pass untaxed and unmolested. A rare usage at a Kashmirian custom-house!

It should have been before noticed, that our patron, from the lameness of his hand, and a general infirm state of body, was obliged to travel in a litter; a species of carriage different from any seen in the southern quarters of India. The frame, of four slight pieces of wood, is about four feet and a half long, and three in breadth, with a bottom of cotton lacing, or split canes, interwoven. Two stout bamboo poles project three feet from the end of the frame and are fastened to its outward sides by iron rings. The extremities of these bamboos are loosely connected by folds of cords, into which is fixed, by closely twisting and binding at the centre, a thick pole, three feet long; and, by these central poles, the litter, or, as it is here called, the Sampan, is supported on the shoulders of four men. This conveyance, you will see, affords no shelter against any inclemency of the weather, which is braved at all seasons by these men of the mountains,

In the passage of some of the steep hills, the Khan was obliged to walk; and it seemed to me surprising, that the bearers were able to carry the litter over them. The Kashmirians, who are the ordinary travellers of this road, use sandals made of straw rope, as an approved defence of their feet, and to save their shoes. On leaving Sumboo, I had been advised to adopt this practice, but, my feet not being proof against the rough collision of the straw, I soon became lame, and threw off my sandals.

In the vicinity of Veere Naug is seen; a torrent of water bursting from the side of a mountain with impetuous force, and immediately forming a considerable stream, which contributes, with numerous other rivulets, to fertilize the valley of Kashmire. On the spot, where this piece of water reaches the plain, a bason of a square form has been constructed, it is said, by the emperor Jehanguir, for receiving and discharging the current; and the trees, of various kinds, which ever spread the borders of the bason, at once give an ornament to the scene, and a grateful shade to the inhabitants of that quarter, who, in the summer season, make it a place of common resort.

The road from Veere Naug leads through a country, exhibiting that store of luxuriant imagery, which is produced by a happy disposition of hill, dale, wood, and water; and, that these rare excellencies of nature might be displayed in their full glory, it was the season of spring, when the trees, the apple, pear, the peach, apricot, the cherry and mulberry, bore a variegated load of blossom. The clusters, also, of the red and white rose, with an infinite class of flowering shrubs, presented a view so gaily decked, that no extraordinary warmth of imagination was required, to fancy that I stood, at least, on a province of fairyland.

Except the mulberry, I do not believe that this country produces any species of the fruits of India, and but few of its vegetables; such is the change effected within a space of two degrees of latitude: this sudden revolution of climate cannot be ascribed to the northern situation of Kashmire, which is little more than two hundred miles from Lahore, where many of the fruits of southern India come to maturity, but to the surrounding snowy mountains, and, an highly elevated land; which the Hindoos say, though very widely, is three perpendicular miles higher than the Punjab.

On the 26th of April, at Durroo or Luroo, a small, but very populous town, seven cosses from Bannaul, where our Khan and his suite were hospitably received by the chief, and lodged that night at his house. Our entertainment, and the cordial behaviour of the host, made us a general recompence for the fatigues of the journey; and in an instant, forgot the pains of my bruised feet, in the pleasant comparison between a commodious shelter and the boisterous weather of the mountains.

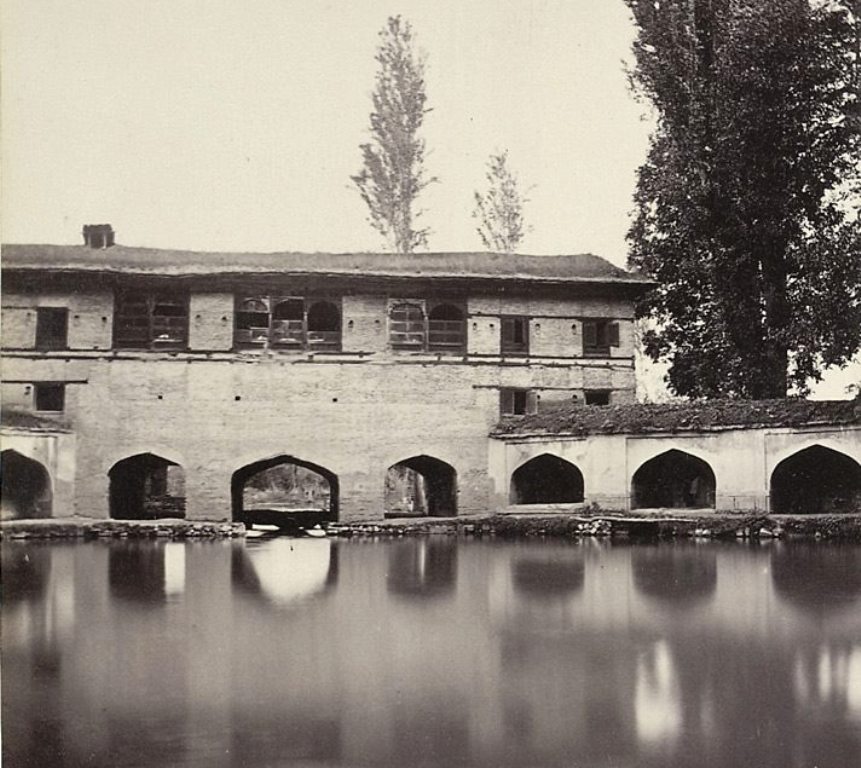

In Islamabad

On the 27th, at Islamabad five cosses, a large town, situated on the north side of the river Jalum, which is here springing from the mountains, or penetrating them in narrow openings. At this place the Jalam, over which a wooden bridge is built, is about eighty yards across, and, from the level surface of the country has a gentle current. Our party, this evening, hired-a boat to proceed to the city, and had gone more than five miles, when a written order arrived, in an evil hour, requiring us to return and remain at Islamabad, until a passport should be obtained from the court. This check infused a general gloom, and rendered our situation, already confined and irksome, almost comfortless. The boat, a very small one, was scantily covered with a slender mat; and the wind, current, and a heavy rain, had set in against us. The rain continued incessantly the whole night; and, though my bedding was drenched with rain, I received no injury from having lain on it several hours.

After expressing my grateful acknowledgements to a hale constitution, I am induced to ascribe a great share of the prevention of sickness on this, as on other occasions, to the frequent use of tobacco, which manifestly possesses the property of defending the body against the impression of damps and cold, or impure air, which, from the thick ranges of wood and hills, is tainted with noxious vapours, produces fevers of a malignant kind; and I am prompted to attribute the good health I enjoyed in those parts, to the common habit of smoking tobacco.

Our party was greatly surprised at the receipt of this very unseasonable mandate, as we had, during the day, occupied one of the most public places of the town, where most of the principal people visited Zulphucar Khan, supplied him with provisions, and were apprized of his intention to depart in the evening. But it had been issued, I believe, by the governor of the town, in resentment of the Khan not visiting him; and operated with a quick force on the minds of all the men, and even the children of Islamabad, who, but the short day before, from treating us with a studied kindness, would now pass our quarters without notice.

A Tyrant’s Rule

Zulphucar Khan informs me that the chief of Kashmire, though a youth, stands in the foremost rank of tyrants; and, that the exactions, of a Hindoo custom-house, will soon be forgotten in the oppression of his government. The one, he said, affects a trifling portion of the property; the other, involves fortune and life.

Two or three days after our arrival at Islamabad, the Dewan, or principal officer of the governor of Kashmire, encamped in our vicinity; and, being acquainted with Zulphucar Khan, obtained permission for the procedure of our party to the city. It is here necessary to observe, that no person, except by stealth, can enter or depart from Kashmire, without an order, marked with the seal of government. The Dewan, attracted, I suppose, by the appearance of so white a person, made some enquiry into the nature of my occupation and views. I told the old story of a Turk travelling towards his country, with the addition, that, to avoid the Sicque territory, I had taken the route of Kashmire, where I hoped to experience the benefit of his protection.

Our party being directed to attend the Dewan, and to form a part of his domestic suite, we proceeded by water, on the afternoon of the 3d of May, to, Bhyteepour, nine cosses, a village situated on the northern bank of the Jalum. In the vicinity of Bhyteepour are seen the remains of a Hindoo temple, which, though impaired by the ravages of time, and more by the destructive hand of the Mahometans, still bore evident marks of a superior taste and sculpture.

On the 7th, the Dewan came to Pamper, whence I went to the city, a distance of seven cusses, in his boat, which, though in Kashmire was thought magnificent, would not have been disgraced in the station of a kitchen tender to a Bengal badgero. The boats of Kashmire are long and narrow, and are rowed with paddles; from the stern, which is a little elevated, to the centre, a tilt of mats is extended for the shelter of passengers or merchandize. The country being intersected with numerous streams, navigable for small vessels, great advantage and conveniency would arise to it from the water conveyance, especially in its interior commerce, did not the miserable policy of the Afghan government crush the spirit of the people.

The City of Kashmir

The city, which in the ancient annals of India was known by the name of Siringnaghur, but now by that of the province at large, extends about three miles on each side of the river Jalum, over which are four or five wooden bridges, and occupies in some part of its breadth, which is irregular, about two miles. The houses, many of them two and three stories high, are slightly built of brick and mortar, with a large intermixture of timber. On a standing roof of wood is laid a covering of fine earth, which shelters the building from the great quantity of snow that falls in the winter season. This fence communicates an equal warmth in winter, as a refreshing coolness in the summer season, when the tops of the houses, which are planted with a variety of flowers, exhibit at a distance the spacious view of a beautifully chequered parterre. The streets are narrow and choked with the filth of the inhabitants, who are proverbially unclean. No buildings are seen in this city worthy of remark; though the Kashmirians boast much of a wooden mosque, called the Jumah Musjid, erected by one of the emperors of Hindostan; but its claim to distinction is very moderate.

The subabdar, or governor of Kashmire resides in a fortress called Shere Ghur, occupying the southeast quarter of the city, where most of his officers and troops are also quartered.

The benefits, which this city enjoys of a mild salubrious air, a river flowing through its centre, of many large and commodious houses, are essentially alloyed by its confined construction, and the extreme filthiness of the people. The covered floating baths, which are ranged along the sides of the river, give the only testimony of conveniency or order; such baths are much wanted by the Indian Mahometans, who, from the climate and their religion, are obliged to make frequent ablutions; and, in preventing the exposure of their women on these occasions, to adopt laborious precautions.

Srinagar’s Lake

The lake of Kashmire, or in the provincial language, the Dall, long celebrated for its beauties, and the pleasure it affords to the inhabitants of this country, extends from the north-east quarter of the city, in an oval circumference of five or six miles, and joins the Jalum by, a narrow channel, near the suburbs. On the entrance to the eastward is seen a detached hill, on which some devout Mahometan has dedicated a temple to the great king Solomon, whose memory in Kashmire is held in profound veneration.

The legends of the country assert, that Solomon visited this valley, and finding it covered, except the eminence now mentioned, with a noxious water, which had no outlet, he opened a passage in the mountains and gave to Kashmire its beautiful plains. The Tucht Suliman, the name bestowed by the Mahometans on the hill, forms one side of a grand portal to the lake, and on the other stands a lower hill, which, in the Hinduee, is called Hirney Purvet, or the green hill, a name probably adopted from its being covered with gardens and orchards.

On the summit of the Hirney Purvet, the Kashmirians have erected a mosque to the honour of a Muckdoom Saheb, who is as famous in their tales, as Thomas-a-Becket in those of Canterbury. The men never undertake a business of moment without consulting Muckdoom Saheb; and when a Kashmirian woman wants a handsome husband or a chopping boy, she addresses her prayer to the ministers of this saint, who are said to seldom fail in gratifying her wish. The northern view of the lake is terminated, at the distance of twelve miles, by a detached range of mountains, which slope from the centre to each angle; and from the base, a spacious plain, preserved in constant verdure by numerous streams, extends with an easy declivity to the margin of the water.

In the centre of the plain, as it approaches the lake, one of the Delhi emperors, I believe Shah Jehan, constructed a spacious garden, called the Shalimar, which is abundantly stored with fruit trees and flowering shrubs. Some of the rivulets which intersect the plain are led into a canal at the back of the garden and flowing through its centre, or occasionally thrown into a variety of waterworks, compose the chief beauty of the Shalimar. To decorate this spot, the Mogul princes of India have displayed an equal magnificence and taste; especially Jehan Gheer, who, with the enchanting Noor Mahl, made Kashmire his usual residence during the summer months, and largely contributed to improve its natural advantages. On arches thrown over the canal, are erected, at equal distances, four or five suites of apartments, each consisting of a saloon, with four rooms at the angles, where the followers of the court attend, and the servants prepare sherbets, coffee, and the Hookah. The frame of the doors of the principal saloon is composed of pieces of a stone of a black colour, streaked with yellow lines, and of a closer grain and higher polish than porphyry. They were taken, it is said, from an Hindoo temple, by one of the Mogul princes, and esteemed of great value.

The canal of the Shalimar is constructed of masonry as far as the lower pavilion, from whence the stream is conveyed through a bed of earth, in the centre of an avenue of spreading trees, to the lake, which, with other streams of a lesser note; it supplies and refreshes. The other sides of the lake are occupied by gardens of an inferior description; though two of them, the property of the government, deserve a distinct notice for their size and pleasant appearance; the Baugh Nusseem, lying on the north-west, and the Baugh Nishat, on the south-east quarter of the Shalimar,

The numerous small islands emerging from the lake, have also a happy effect in ornamenting the scene. One of a square form is called the Char Chinaur, from having at each of the angles a plane-tree; but one of them, and a pavilion that was erected in the centre, has gone to decay, as have all their monuments of the Moguls, except the Shalimar, which is preserved in good order, and is often visited by the governor, whom I have seen there, with his officers and the principal inhabitants of the city. Since the dismemberment of Kashmire from the empire of Hindostan, it has been subject to the Afghans, who possessing neither the genius nor the liberality of the Moguls, have suffered its elegant structures to crumble into ruins, and to held out against them a severe testimony of the barbarity of their nation.

Amir Khan, a Persian, one of the late governors of Kashmire, erected a fortified palace on the eastern side of the lake; but the materials have been so unsubstantial, that though of not more than eight years standing, it cannot now with safety be inhabited. He used to pass much of his time in this retreat, which was curiously adapted to the enjoyment of the various species of Asiatic luxury; and he is still spoken of in terms of affection and regret, for, like them, he was gay, voluptuous, and much addicted to the pleasures of the table. There is not a boatman or his wife that does not speak of this Khan with rapture, and ascribe to him a once abundant livelihood. This governor, like many of his predecessors, trusting in the natural strength of his province, and its distance from the capital, rebelled against his master. The force sent against him was small and ill appointed and might have been easily repelled by a few resolute men stationed in the passes. But in the hour of need, he was abandoned by the pusillanimous fickle Kashmirians, who reconciled their conduct to the Persian, by urging, that if he had remained in Kashmire, he would have converted them all to the faith of Ali, and cut them off from the hope of salvation. A Kashmirian must have been grievously embarrassed to justify his conduct when he ascribed it to any principle of religion; for he is a Hindoo, a Mahometan, and would become a Christian if a priest were at hand, according to the fashion or interest of the day.

(This is the first part of the series on George Forester’s Kashmir travelogue. Read the second part here.)