Carl Alexander Anselm Baron von Hügel (1795-1870), a prominent naturalist from Vienna spent more than five years in India. He spent part good time visiting Kashmir in 1835. Though most of his observations and findings are properly documented in his three-volume book, ‘Travels In Kashmir and the Panjab’, the Austrian botanist and soldier made various speeches before he sat to write the book. In this speech, Hugel offers some quick details of Kashmir he saw in Sikh rule

Kashmir in a political and financial point of view, has been much overrated; not in a picturesque one. The valley in its length, from northwest to south-east by east is little more than 80 miles long; the breadth crossing the former line, varying from 30 miles to 6. I speak of the actual plains: from the eternal snow of the Pir Panjahl to the Tibet

Panjihl (Panchal) are 50 to 60 miles: both ranges run nearly parallel in the first direction, with a great number of peaks. The height of the passes from Bimbar to Kashmir, and that from Kashmir to Iscardo (Askardu) is the same, 13,000 feet; the highest point of the Pir Panjahl, 15,000 feet by the boiling point. The city of Kashmir 6,300 feet.

Population: Four years ago about 800,000; now not exceeding 200,000. The valley is divided in 36 perganahs, containing ten towns and 2,200 villages. Kashmir town contains still 40,000 inhabitants; Chupinian (Shopian), 3000; Islamabad (Anantnag) and Pampur (Pampore), 2000. It was not the bad administration of the Sikhs, but a famine brought on by frost at the time the rice was in flower, and cholera in consequence of it, that reduced the population to one-fourth of the former number by death and emigration; many villages are entirely deserted. Chirar (Chrar-e-Sharief) town contains now 2000 houses and only 150 inhabitants!

Brahmans, the only Hindus in Kashmir, 25,000 in 2000 families; they are Vishnuvaites and Sivaites, divided into three divisions, who all intermarry: they are darker than the other inhabitants, owing to a colony sent for from the Dekhan (Deccan) about 800 years ago, after the aboriginal Brahman race was nearly extinguished by the persecution of the Muhammedans.

There is not in the valley the slightest appearance of its having been drained: the pass-through which the Jhelum found its way is one of the most beautiful of the world: its bed 1000-1500 feet deep: I do not believe more in the traditions of the Kashmirian Brahmans than in the fables of Manethon.

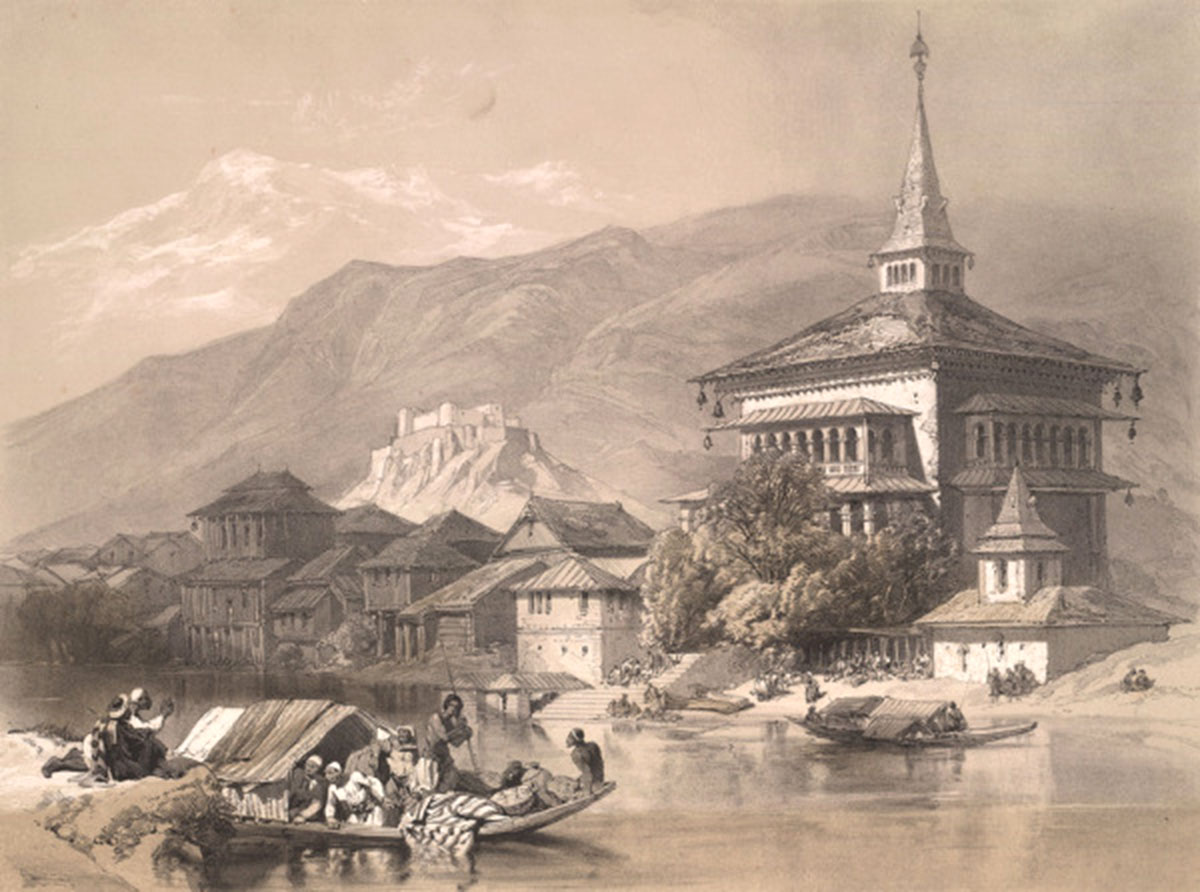

All the remaining temples are Bauddha, of a different shape from any

I have ever seen; only one small one reminds me of the caves of Ellora:

I have observed no Dagoba, Koran Pandan, near Islamabad, Anantnag of old, is not only the largest ruin of Kashmir but one of the splendid ruins of the world: noble proportions; material black marble. I was nearly 1ed into error at first thinking its form Grecian. The building had nothing on a closer examination, which could justify such a hypothesis. Very few temples remain in Kashmir in tolerable preservation, having mostly been destroyed by a fanatic Musalman, whose zeal did not succeed in overturning them all.

Revenue: Last year very nearly nothing, Ranjit Singh wishing that the country should recover: this year (1836) he asks 23 lakhs from the Governor, Mohan Singh, which the country cannot give. The emigration has brought to the Panjab and Hindustan many shawl manufacturers, and Kashmir will most likely never yield again what it did a few years ago. Nurpur, Lodiana, and many other places can bring to the market shawls cheaper than Kashmir, where every article of food is dearer than in the Panjab and Hindustan.

Access: Twelve passes, Pansahl in the Kashmir language (from which Pir

Pansahl of the Musalmans) now exist; three to Tibet (Iscardo and Ladakh); eight to the Panjab; one to the west. In former times, there were only seven: the defence of which was entrusted to Malliks with hereditary appointments: four passes are open the whole year: one to Ladakh, the western pass, (Baramulla,) and two to the south.

The 12 passes are Banderpur Pass, Kandrihall Pass, Naubuck Pass, Sagam Pass, Banhall Pass, Kulnarwah Pass, Schupianka Pass, Ningmaruk Tera Pass to Prunch (Poonch), twenty-six miles to the highest point of the pass; Tossemaidan Pass to Prunch, over the plains of Tasse, twenty-six miles to the highest point; Ferospur Pass to Prunch, twenty-eight miles to the highest point; BaramuIIa Pass, by Canhorn to Prunch, fifty-two miles to the highest point; Baramulla Pass, by Mozufferabad, the Tchikri of old, to Attock.

All the passes to Prunch are of a very recent date, and for this reason no Mallik exist. It is the same with Baramulla, the now-existing pass being made by the Patans (Pathans) eighty years ago; which appears to throw some doubt on Acber’s (emperor Akbar) entering the valley from that direction. He found, at all events, the difficulties so great, that he thought it unnecessary to appoint a Mallik.

All the passes of Kashmir go over the highest mountains, with the exception of the Baramulla, or Western Pass, which follows the course of the Jhylum (Jhelum). It is rather extraordinary that this river comes from a part of the valley where no snowy ranges exist, and runs in the direction where they rise without termination one over the other It is a peculiar feature of the three largest rivers of the Panjab, the Sutlej, the Jhylum, and the Attock, that they run for a considerable time in the direction of the formation of the highest ridge: the first and the last having their sources beyond the highest mountains of it.

Before the Moguls conquered Kashmir, seven passes existed leading to the valley. Acber entrusted them to hereditary Malliks, allotting them villages, for which they were obliged to defend the pass entrusted to them, and in case of war to appear in the field with a certain number of soldiers, varying from 100 to 500, which at this moment they are unable to do.

- Acber gave them power of life and death; the Patans reduced this to the power of cutting off noses and ears, and now their power consists in fines. The following is a list of them, beginning to the north of the town, and turning to the east:

2. Dellawer Mallik, Banderpur Panjahl (pass), by Kuihama to Iscardu; the highest point of the pass thirty-four miles from the town.

3. Rossul Mallik, Kandriball Panjahl, to Iscardu

4. Maredwaderan Mallik, the same Panjahl to Ladak. This pass divides when on the highest point of it, fifty miles from the town.

5. Naubuck Nai Mallik, Naubuk Panjahl, or Tibet Panjahl, by Islamabad and Naubuk to Ladak; the highest point of the pass seventy-four miles from the town.

6. Shahaabadka Mallik, Sagam Panjahl nur Banhall Panjahl. Both to Kishtewar and Jummu; the former fifty, the latter forty-six miles, to the highest point.

7. Kulnarwah Mallik. Kulnarnah Panjahl to Jummu, fifty-four miles to the highest point.

8. Shupianka Mallik, Pir Panjahl, sixty miles to the highest point.

The only trace of fossil remains in the valley is in a limestone, which contained small shells.

Geography

The valley of Kashmir has on its south side gently rising hills, the last declivities of the Pir Panjahl, covered with the most luxuriant vegetation; and the eye gradually ascends over their beautiful forms and colour to the snowy range with its thousand peaks. On this side more or less extensive valleys are formed, in the centre of which the purest mountain-streams flow, and form, higher up, innumerable cascades.

In this direction the zoologist and botanist must bend his steps; here the thickest woods are interspersed with open plains, and the wanderer through them finds neither in the former a tree felled by man, nor in the latter, the countless flowers bent by the steps of a living being. Here is perfect solitude; there, treasures of vegetation are heaped up without an eye to enjoy them; and the silence is only interrupted by the notes of the blackbird or the bulbul.

The travellers were surprised to find the mountains this temperate climate very cold; with their southern exposure bare and uncovered; and to reach the highest point, and to see, facing north, plains covered with flowers under the snowline, and then the richest forests descending to the valley.

A Nobleman’s Park

Nature has done much for Kashmir, art more; the whole valley is like a nobleman’s park: the villager, being surrounded with fruit trees, and having in their centre immense plane and poplar trees, form large masses, having between them one sheet of cultivation, through which the noble river winds itself in elegant sweeps.

The botany of Kashmir is not rich, and is very nearly allied to that of the Himalaya, between Massuri and Simlah: in the valley itself not a plant is to be seen of indigenous origin: the northern declivity of the mountains is rich in vegetation, the southern steep and barren. The Chinar is the Plantanus Orientalis, which so far from being a native of Kashmir does there produce no germinating seeds, and is multiplied by cuttings, which, since the Moghul Emperor, have not been kept up. It is a very extraordinary phenomenon to witness the Nilumbium Specium growing where the orange tree is destroyed by frost. Misri yeleb is not a native of Kashmir.

The Volcanic Fragrance

The burning gases at Jwalamuki are of a very extraordinary nature, nothing of sulphur or naphtha in them. They have a most delicious smell, something like a French perfume with ambergris. The flames, about 10 in number, come out of a dark grey sandstone on perpendicular places: temples are built over them: I attributed the effect to priestcraft, until in one of the temples called Ghurka Debi, I was allowed to try experiments, and remained alone: I blew out the flame, which did not re-ignite from itself: there is nothing particular on the places where the flame came out: no change in the colour or substance of the stone, or in its hardness.

Water in small quantity is, formed in little reservoirs under the flames, being the produce of them: this water takes fire too from time to time, when enough inflammable matter is collected on the surface. I took a bottle of it for you, which Captain Wade will be so kind as to forward to you for examination: it has, however, now undergone a terrible alteration by putrefaction, and I am afraid that you will not be able to analyse it. The taste of it when fresh can distinguish nothing of its composition: it is not unpleasant to drink, and of a milky-greenish colour. No traces of volcanic matter near it.

I have picked up many coins, which appear to me new; of some I am certain: those of the Kashmirian kings, of the Bauddha time, found near the town Bij Bahara (no doubt a corruption of Vidya Vihara, temple of Wisdom, if my Sanscrit does not forsake me): I intended sending them to you, but they found their way in one of my tin boxes: I cannot guess in which, and for thin reason do not open them: whenever I come to

Them, I shall send you them, or their exact likeness.

(This write-up is based on a speech of the author soon after his Kashmir travel that was secured from two different sources and edited enough to avoid repetition.)