Around 1900, a British surgeon during his long tenure in Kashmir wrote Duke’s Guidebook to Kashmir, primarily aimed at European tourists. His description of Kashmir is phenomenal in detail that offers an interesting and graphic description of the Kashmir in 1900. Joshua M Duke’s detailed narrative of the Srinagar city, being published in two parts, might sound Greek to the residents in the twenty-first century

About the author: Lieut-Colonel Joshua Duke (1847-February 13, 1920) was educated at St Pal’s School and at St Thomas’s and Guy’s Hospitals. Later, he took the diploma of MRCS and LSA in 1868 and was subsequently appointed a ship surgeon to Melbourne where he served as resident assistant surgeon to the Bendigo Hospital. On his return, he joined the IMS in 1872, retiring with the rank of brigade surgeon in November 1902. The last 20 years of his service was spent chiefly in political employment; he was for several years residency surgeon in Kashmir and accompanied a special mission to Gilgit. He served in the Afghan war of 1870-80. He was the author of several works including the re-writing and editing of Ince’s Kashmir Handbook – from 1888 to 1908, the two last being published under his own name.

Srinagar, Sirvea Nagar, the city of the Sun, the Capital of Kashmir proper, as distinct from Jammu, was built by Raja Pravarasne about the beginning of the sixth century. It is near the centre of the Valley, being 34 miles distant by land from Baramulla and Islamabad, respectively. Its elevation is 5,250 feet above the sea, the houses are said to number 20,000 and the population is about 120,000.

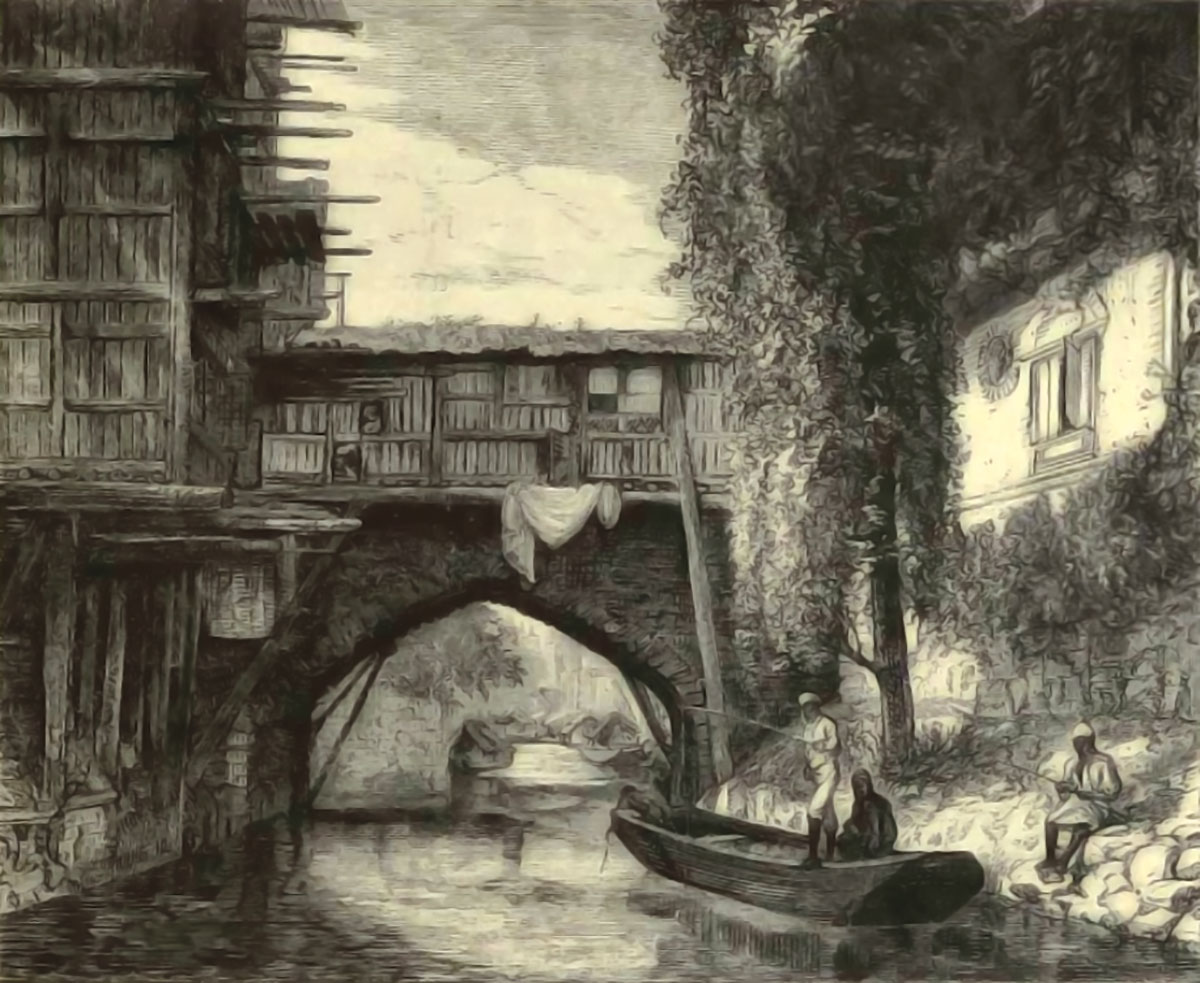

The City is built on either hank of the Jhelum, covering in length to an extent of about two and a quarter miles. The suburbs on the North side stretch back for a considerable distance. The houses are mostly built of wood, and fires are of frequent occurrence. In the great fire of 1892, 1300 houses were burnt down, the disaster is followed by a terrible visitation of cholera.

In 1898, the Maharajgunge Bazaar, the Emporium of Kashmir work was destroyed and gutted by fire. Formerly, the city was rarely visited by Europeans, and a second visit was never paid, for the filth and the stretch in the street were intolerable. Of late year, especially since the recent outbreaks of cholera, sanitation has rapidly advanced. The streets of Srinagar now compare favourably with any other city, though, of course, a vast deal remains to be done in the sideways and alleys.

A great deal of money was spent by the State in 1901. One must recollect that Srinagar, and Kashmir generally (for the villages in some of the most lovely spots in the world are still in a very parlous stale) has existed for centuries surrounded by filth; and, as was truly written in 1892, of the inhabitants of their chief city, they breathe filth, sleep on it, are steeped in it, and are surrounded by it on every side. They have, however, now, no occasion to drink it as before, for a pure water tap supply is available at all points. The cleansing of this Augean Stable, though tedious and lengthy is nevertheless being slowly accomplished.

On his arrival at Srinagar, the visitor is generally waited on by the Baboo in charge of visitors, and is asked to record his name and address in the book. The Baboo’s residence is near the Mail Cart Stables, at the end and back of the Chenar Bagh. He is an authority on most points affecting the interests and comfort of visitors, and from him can be obtained a copy of local rules for travellers, in force at the time, He also assists in procuring transport. He was formerly the referee on all points connected with the price of articles, copper, silver, etc.

The bungalows formerly set apart for married people as well as bachelor have practically ceased to exist. Even the barracks are now permanently occupied. At present, the five houses on Sir Amar Singh’s estate at Gupkar, four miles from the first bridge, are the only buildings available. They are well situated, with a charming view of the lake and are most enjoyable residences for the spring and early summer. But in July and August, the heat is enervating and the mosquitoes are troublesome.

It is probable, in the near future that more houses would be built for renting, by private individuals, native gentlemen. In the meantime house-boats, some quite palatial in size, take their place. Then, too, the Srinagar hotel, built by the Durbar, rented and opened by Mr Nedou in 1900, supplies a long-felt want. The visitor ha, therefore, the choice of tents, a house-boat, a doongah or country boat, and the hotel.

The camping ground for bachelors is the Chenar Bagh, where there is grand shade, but the ground is often flooded. For married visitors, there is the Munshi Bagh, with its limited shade and the Sonawar Bagh beyond, on the Islamabad road. The Nasim Bagh on the Dal is a favourite place with many.

Of the many interesting places in the Valley, the Takht-i-Suliman should be first visited, as it gives at once a clear view of the City and its suburbs, as well of the glorious mountain range which surrounds it on all sides. The Takht-i-Suliman, or throne of Solomon, is 6,263 above the sea, and, therefore, a clear thousand feet above Srinagar.

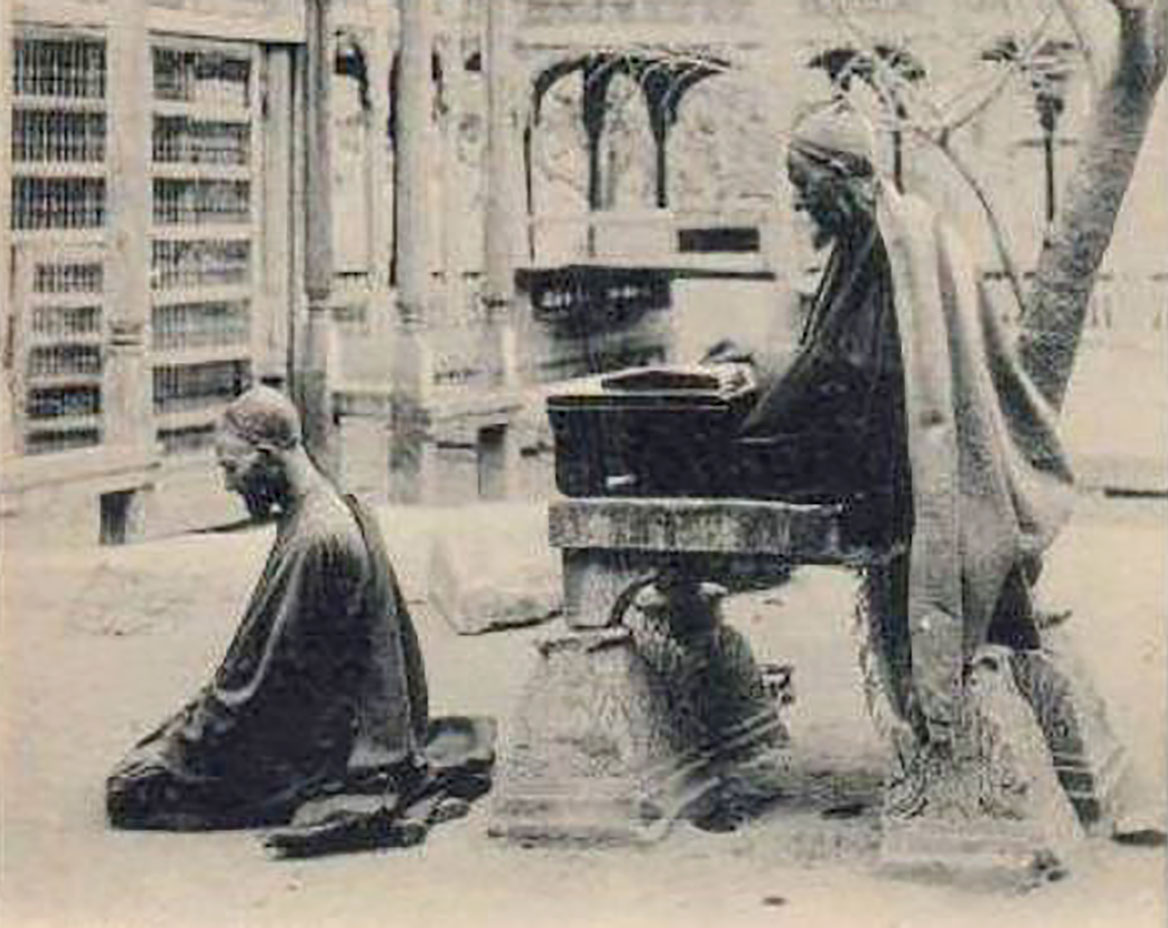

The original structure is said to have been erected by Jaloka, son of Asoka, BC 220, and the date of the modern building is given as AD 238. It is raised upon an octagonal base of solid masonry and is approached by stone steps on the Eastern side. On entering the outer arch or gateway, one ascends a flight of narrow slippery, limestone steps. The temple itself is small, with massive walls eight feet in thickness. The roof is supported on four octagonal limestone pillars. In the centre is a black polished lingam or stone of colossal size. This lingam is of recent date, the original having been broken; and the road on the west side is said to have been improved, to allow of this enormous weight being carried up. The Priest who supplies the stone with oil, dowers, lives below; but is generally present to receive any visitor, in the hope of reward.

On the South-west side, is a stone tank and other ruins on the north. But let us step outside on the stone platform, which surrounds this curious edifice, and slowly take in the scene that lies around and below us. During his brief visit to the Valley in 1859, Sir R Temple spent all his spare time in composing a panoramic view of the Valley from this spot, producing a wonderfully interesting picture. This drawing holds as good now as then, with the exception of a few additions to the suburbs.

On a really clear morning or evening, when the snow lies deep on the mountains, this view is probably one of the finest in the world. The grand panorama stretched before us comprises nearly the whole Valley, from the City to the Wular Lake, from the river, winding in those curious, artificial looking curves that suggested the Kashmir shawl patterns, to the serrated profile of the snowy Pir Panjal Range. To the North and West, the mountain rises over the mountain, peak overshadows peak, in wild grandeur. The precipitous mountain wall that overlooks the City Lake is topped by the triple peak of Madadeo, while the snowy cone of Harmukh just appears above the mountains bordering the Sind Valley. Looking South-east, the fine peak of Wastarwan jilts out far into the Valley, while for a hundred miles, South-east to South-west, stretch the sharp peaks of the Pir Panjal Mountains, standing clear above the dark pine-clad valleys below them.

To the South, immediately below, lies the Munshi Bagh, its houses and roads, the Cottage Hospital, the Church, the Residency, the Polo ground, the remains of the straight Poplar Avenue, with the Hotel in the centre to the right, the line of the Chenar Bagh, all neatly mapped out. The chief new additions since Temple’s time are the Church, the Hotel, and the Silk Factory – across the river beyond the City SSW. The road to Baramula can be seen for many miles stretching west, a streak of young poplars. One also sees how completely the City is surrounded on all sides by swamps, which no doubt helps to make it unhealthy. Turning towards the Dal Lake, all the points of interest mentioned later on can be made out, the open pieces of water, the floating gardens, the Perimahal, the Nishat Pavilion, and the dark foliage that indicates the position of the Shalimar, Nasim Baghs, the Isle of Chenars — all the localities described in Lalla Rookh.

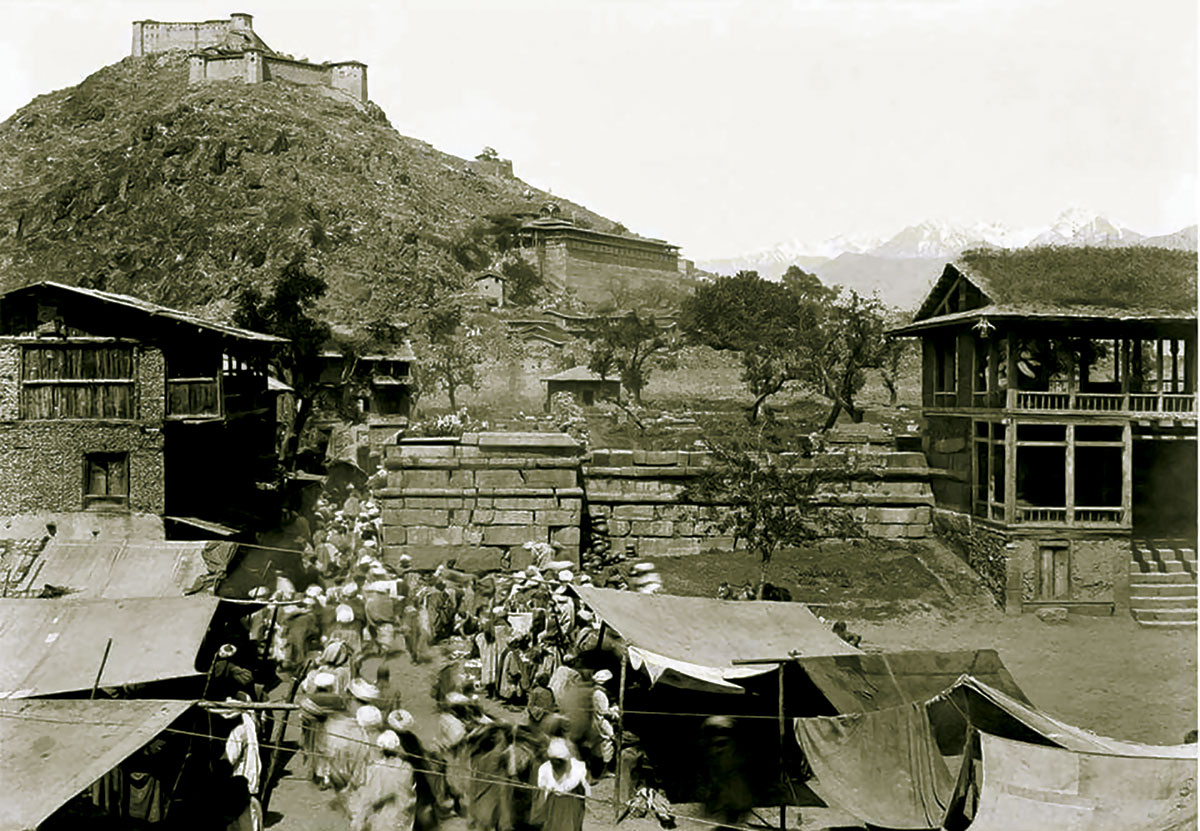

Hari Parbat

The Fort on the Hill of Hari Parbat is worth a visit, on account of the view obtained from it. Hari Parbat is an isolated hill 250 feet above the lake, surmounted by a fort and wall. Standing to the North of the City, it is a conspicuous object. It marks the position of the City and can be seen for twenty miles from the West side of the Valley.

The fort and wall were built by Akbar, AD 1590, to overawe the Capital and protect the treasury. The interior is disappointing. The view from the summit is very fine. The City, spread out on the South, resembles a green carpet, for the roofs of the houses are clothed with grass and other plants, and by the aid of a pair of binoculars, every building of interest may be easily distinguished.

The Takht-i-Suliman stands out boldly on the South-east, while on the East lies the Dal or City Lake, which is here seen to the best advantage; on the Southern side of the hill is a stone mosque, a large irregular mass called the Akhun Mullah Shah Musjid, after the tutor and spiritual guide of the Emperior Jehangir; to the West of this is the shrine of Shah Hamza, otherwise Makhdum Sahib, which is of great sanctity among the Mahomedans; and on the Northern side of the bill is a large and irregular mass of rock, which has been dedicated by the Hindus to Vishnu; it is covered with red pigment, and is much frequented by the Hindu community as a place of worship. If the traveller at starting sends his boat round to the foot of the hill on the Dal, he can return by water.

Having seen the great panorama from the Takht, and the more limited view from the Hari Parbat Hill a few places of interest about Srinagar may be noted.

The Residency stands in a large enclosure on the river bank, between the Library and the Post Office. It is a handsome double storied building, with a fine hall and central staircase. The gardens are well shaded by Chenars. Above it is the Library and new Recreation room opened in 1901, together with Tennis and Badminton Courts. The Library is well stocked with books; the Golf Links adjoin the Hotel. They consist of 9 holes, and, owing to the limited space, run backwards and forwards in an annoying way, but are very easy. The golfer should always bring his clubs, for the 8-hole link at Gulmarg is one of the finest in India.

The Munshi Bagh is still used as a camp, but the shade is limited. The Sonawar Bagh, half a mile higher up, is generally crowded. The Poplar Avenue, which runs in front of the Hotel, was originally planted in 1809 by the Pathan Governor of Kashmir. It is a mile and a quarter in length and was used as a race-course. The poplars were cut down in the nineties and young cuttings are now growing. The avenue also contained 15 Chenars, which still remain.

The Post Office and the Tonga terminus are opposite the Hotel on the other side of the Polo ground. Below them, on the river’s bank, are the two last of the old style of houses, now occupied by the Secretary of the Game Laws, and the Gilgit Transport Office. Below these houses are the shops and agencies, the Panjab Banking Company standing a little back. The Government Telegraph Office is just behind it.

On the opposite side of the river is the old picturesque house, the Lal Mandi, formerly used for banquets and occasionally for distinguished guests. The Duke and Duchess of Connaught were put up here in 1884.

It is now the State Museum and contains sufficient interest to make it worthy of a visit. One must cross over by boat. This shows the necessity of a bridge over the river at the Munshi Bagh, which would open out the country on this side, and allow of extra rides and walks in the direction of Shupyan and Pampore, and also give short cuts to the Silk Factory and the State Hospital. To reach the Silk Factory the road crosses the first bridge, then turns down the interesting bazaar to the left, skirts the right of the parade ground; and the factories are about a mile ahead lying on the left bank of the Dudhgunga river, which is bridged here. The houses of the Staff are on the left of the road. The steam whistle of the factory, calling in the labourers, is daily heard for several months while the machinery is working.

By the middle of June, the exodus of visitors commences, for the heat, mosquitoes, etc, in Srinagar are trying, and genial climates are at every hand. Some, the majority, make for Gulmarg (8,500’), a bracing climate spoiled only by rain; others go to the rival colony at Pahalgam, two marches up the Liddar Valley.

Down the River

With a view to describing the chief points of interest, let us start at the upper end of the Munshi Bagh, where a side channel, or ditch, separating the Sonawar from the Munshi Bagh, joins the right bank of the river. The first two are State houses, privately rented. No 3 is an old style double-storied building occupied by the Mission – Drs Neve. Then comes the modern Queen Anne style house of the Settlement Commissioner. Next, are the barracks in two blocks; then the Accountant-General’s quarters, and beyond, the new-style villa of the State Engineer.

Below, two old-fashioned bungalows, and the modern dwelling of the Military Instructors. Behind this are the Church and the Chaplain’s house. The channel running to the Dal Lake joins in on the right, guarded by flood gates. A little below stands the Library and the Recreation Room, with a covered way over the river. The Residency, standing back in its own grounds, comes next – a double-storied building built in 1 886 to replace the old single-storied house rendered unsafe by the earthquakes of 1885. Below it is the island, the East end being occupied by a Fakeer’s quarters, and the rest often used as a camping ground.

Below the Residency come the Residency Clerks’ and Vakeels’ quarters, then the Post Office and Tonga terminus adjoining. Two more old houses, relics of the past, are next, now used as the offices of Secretary, Kashmir Game Laws and the Gilgit Transport. Then come the shops and agencies. Between the first two shops the Panjab Banking Company lies back in a large compound, and behind it, across the road, is the Government Telegraph Office. Across the river (left bank) is the Lal Mundi, now the State Museum. The new house adjoining belongs to the Revenue Member of Council. Below the Museum is the State Civil and Military Hospital – a fine double-storied building, fitted up to modern requirements, and open to inspection.

Beyond are the houses of the Chief Medical Officer, Kashmir, and the Chief Justice.

(The series concludes next week)