The oldest Protestant Church over the Rustum Gari hill is being revived and renovated by the government under its smart city project. Constructed in 1896, there is a detailed narrative about the community’s struggle, and eventually, the celebrations after the small but powerful Christian missionaries working in Kashmir in the late nineteenth century finally got a proper church in Srinagar

A visit from their diocesan, which marks an epoch in the Kashmir Mission, most happily inaugurated the winter’s work of the little band reassembled at Srinagar in September 1896.

Prayers In Dancing Hall

During the early days of CMS (Christian Missionary Society) work the young English men used to go to Kashmir with the undisguised intention of escaping from the restraints, none too strict, of ordinary Anglo-Indian life; and the only sign that the sahib log had any religion was a gong summoning Europeans once a week to service in a summer-house, formerly used as a dancing hall.

Writing from Srinagar in July 1871, Bishop French says: “British Christianity never shows itself in more fearfully dark and revolting aspect than in these parts. People seem to come here purposed to covenant themselves to all sensuality, and to leave what force of morality they have behind them in India.”

The upper room on the Sheikh Bagh that then served as a place of worship was so ill-appointed that the Bishop had to send for his own camp table when he administered the Holy Communion there. The fierce opposition aroused by his attempt to evangelise the Kashmiris has been described already.

Prohibition

Even in 1883, Mr Clark speaks of Srinagar as the one place where English Christians were actually prohibited from building a church, so bigoted was Runbir Singh. The present Maharaja, however, permitted the erection of a humble wooden structure on the Munshi Bagh, in the compound of the senior CMS missionary, who acts as honorary chaplain, except for the few weeks of spring when a chaplain arrives with the throng of English visitors, moving on later to Gulmarg with them. The Urdu service for native Christians was, as we have seen, held in the waiting room of the hospital.

Exactly twenty-five years after Bishop French penned the sentence just quoted, his successor, Bishop Matthew, came to Kashmir to consecrate three churches: a church at Gulmarg, All Saints’ Church on the Munshi Bagh for the Anglo-Indians, and St Luke’s Church on Rustum Gari for the natives. All three were on ground ceded by the Maharaja to the British Government, and Mr Nethersole, State Engineer to the Kashmir Durbar, was the architect of the two in Srinagar.

For £ 500

The story of the erection of St Luke’s suggests a parable. The walls first raised collapsed, and they discovered that the ground was undermined with Mohammedan tombs; so they set the foundations anew upon a solid rock, and now no building in Kashmir stands more secure. It is a cruciform structure of red brick, with a vaulted roof, ceilings of pretty Kashmir parquetry, lancet windows glazed in geometrical patterns, a gracefully proportioned apsidal chancel, and a carved screen across the nave beyond which non-Christians are seated.

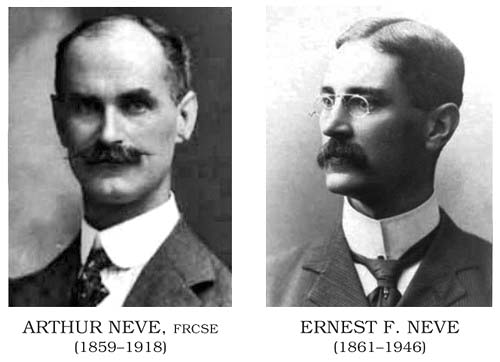

“A most lovely church, pinkish-red inside, like Exeter Cathedral,” is Irene’s description. It accommodates two hundred, and cost about £ 500, less than many a luxurious congregation at home spends on a new organ or a new scheme of lighting that is not really necessary. In the main it was built out of the fees received by the Drs Neve from their wealthier patients; and the furniture and fittings of this, the first Christian church in Kashmir, were likewise almost all freewill offerings of or through those who had already given themselves to God for the evangelisation of that land. Miss Hull gave the font. Miss Pryce-Browne the ewer. Miss Coverdale the lectern. The chancel rails were a gift from one of Irene’s friends in Philadelphia, who wrote to her that “they had already flashed their blessing across the seas to America”; the reading-desk was a gift from the Penshurst Gleaners; the Holy Table represented the proceeds of a lecture on Kashmir delivered in Montreal at Irene’s instigation, – nearly all these things, given by dwellers in three different continents, were of native work in finely carved cedar and walnut wood.

Irene’s own characteristic offering, purchased out of the proceeds of sketches of Kashmir sold in India, Great Britain, and Canada, was the organ, of solid polished oak with a full and sweet tone. She secured the kind interest of Mr Henry Bird in choosing and despatching it from London and lent it for the summer to All Saints’ Church, which had been opened on May 3rd.

First Service

The Bishop of Lahore arrived on September 10th with his chaplain, the Rev Edmund Wigram, son of the late Honorary Secretary of the CMS. Other visitors for the occasion were Colonel Broadbent, C.B., with his wife and daughter, staying at the CEZ House; and the Rev Cecil Barton (CMS, Multan), staying at Holton Cottage. Miss Broadbent became Mrs Cecil Barton in October 1896; and in November 1899, Mr Barton was transferred from Punjab to Srinagar.

Early on September 12th Irene and Miss Howatson were decorating St Luke’s with flowers. Irene thus describes its dedication: “All the Indian and Kashmiri Christians came, and a large number of the English inhabitants, headed by the Resident, Sir Adelbert Talbot. The choir was led by some of our party, and Dr E Neve played the organ.

Dr A Neve received the Bishop and six clergy, who came to the west, or rather east door, as the church is occidented and presented the petition for the dedication of St Luke’s, which was read in Urdu. The Bishop went separately to the font, the lectern, the place of weddings, the place of confirmations, and the Holy Table, praying for a blessing on each.

After the ante-Communion Service, he preached a fine sermon in English, which Mr Wigram rendered into Urdu for the native half of the congregation. The Communion Service in Urdu followed, and it was touching to see aged Qadir Bakhsh coming forward, supported by his son. The dear Bishop, who walked part of the way back with me, said he had never enjoyed such a service more. He is delighted with everything in both churches.”

Daily Service

Henceforth service has taken place daily in St. Luke’s; and from that lofty site its spire witnesses to Christianity throughout Srinagar. “We hope,” says Irene, “it may be to future generations what St Martin’s at Canterbury is to England when Kashmir has indeed become a ‘Happy Valley,’ which, alas! it is very far from being at present.”

The fete for the building fund and organ of All Saints’ in May had been the event of the Kashmir season. Irene had lent sketches to its exhibition, contributed largely to its concerts, and helped to sell at its stalls. This church was consecrated on Sunday, September 13th.

“We have had a most beautiful Consecration,” she writes. “May Pryce-Browne and I have been agreeing that we were never at a more personally helpful service. We were a choir of sixteen, and there was a congregation of about two hundred. The Resident read the petition for its consecration. The offertory sentence was ‘Cast thy burden upon the Lord’ from Elijah, taken as a quartette: soprano, IEVP; alto, Mrs G A Ford; tenor, Mr Barton; bass. Dr E. Neve. There was a choral Communion, the choir being all communicants themselves, as well as a large part of the congregation; it was quietly and reverently done, and so delightful. . . . The evening service was even heartier than that in the morning; many said it was like a home church service. The clever bandmaster, who is organist now, and plays up to a first-rate professional standard, said it was the best service he had ever heard in India. Yet it was certainly no mere performance, but a congregation all praising God together, as in St Mary Abbots.

For anthem, we had my most dearly beloved air and words from A Paul,

O Thou, the true and only Light,

Direct the souls that walk in night,

as a quartette, taken by the four singers of the morning.” At the special request of the chaplain, the Rev. G A Ford, Irene and Mrs Tyndale-Biscoe sang some oratorio solos on the following Tuesday, at a further service attended by many not usually church-goers.

The Bishop

The Bishop also gave the prizes in the School; visited the Hospital, and described it as a model of what a mission hospital should be; consecrated the English cemetery, and held two confirmations – one at All Saints’, where the candidates included two daughters of a Unitarian who had been under the influence of the CMS missionaries; and one in St Luke’s, where eleven candidates, representing seven nationalities, professed their faith.

Having thus “confirmed the souls of the disciples, and exhorted them to continue in the faith,” that “real father in God to all under his jurisdiction” went on his way; and two years later, on December 2nd, 1898, after an episcopate of nearly eleven years, he was suddenly called home. He had preached with all his usual power on the evening of Advent Sunday about the Church’s duty to proclaim the witness of Christ’s Kingdom to the world, exhorting his hearers to be ready, should the summons come that night, to answer gladly, “Even so, come, Lord Jesus.

These were the very last words of his ministry and almost of his life, for before he could pronounce the benediction at the close of the service he was smitten with paralysis, which proved almost immediately fatal.

The Church

Conspicuous on an outlying spur of it, known as the Rustum Gari, beneath which nestles the village of Drogjun, rises now a cruciform building whose tale will be told presently, where the worshippers of Christ gather daily. Its spire points to heaven at a lower elevation than the top of the domed Hindu temple, and it does not actually crown the Rustum Gari. Round the summit of that secondary height runs a fence, above which no one may build, for the Kashmiris believe that he who lives on Rustum Gari will rule Kashmir.

The Hosts Population

The residents in Srinagar, who are to be distinguished from the great tide of visitors to Kashmir that sets in with spring and recedes again in autumn, consist of some fifty or sixty Europeans connected with the military and civil service, engineering, and commerce, varying much in character and in social position. Both with them and with the Eurasian community the missionaries cultivated friendship, enlisting the help of some of them for work that did not demand their own special training or knowledge of languages.

There was the Resident, who always read the lessons in All Saints’ Church, and whom the Maharaja had learned to trust and respect for his known religious principles. There was the Assistant Resident, who had successfully intervened on behalf of the schools. There was the son of a late President of the Royal Academy, whose photographs have familiarised not only the scenery but the mission buildings in Kashmir to many. There was the lady artist, who was Irene’s chief ally during the winter, in which she was the only zenana worker. These two last helped in so many ways that they seemed almost like members of the mission circle.

There was the venerable Colonel, who, with the aid of Qadir Bakhsh, sometimes conducted a service for beggars. He delighted in Irene’s Jacobite songs and well-informed talk about good Scottish families; she brought him heather from the Highlands in 1895, and he brought to show her his treasured heirloom, a sword that had belonged to Prince Charlie. Other unnamed station people there were of whom even the charitable Irene is driven to say: “The worst thing of all in Kashmir is the conduct of some of the English people who find their way to this remote place. It is grievous to hear how the inquiring and intelligent natives point to them as the stumbling blocks in the way of their accepting Christianity. I wish they could be packed off to Antarctica, or other uninhabited regions where there are no poor puzzled non-Christians to be caused to stumble.”

The residents received from as well as gave to the mission. Many attended the daily evening service held by the missionaries in January 1896, during the Week of Universal Prayer, “several of whom seemed really to care.” They mustered also in large numbers in the Library, the rendezvous of the fashionable world of Srinagar, to hear lectures by Dr Neve, one on Recent Progress in New Testament Criticism, one on The Resurrection—A Fact, which attracted English who were not church-goers as well as educated natives, and the whole missionary party prayed that these lectures might bear fruit.

Again, the ennui of winter 1894-95 was to be relieved by a series of concerts in the Library, and they came to the missionaries for really good music, Irene on one occasion taking part in eleven out of eighteen performances, either as vocalist, instrumentalist, or accompanist. Every resident practically was there, and they acknowledged this help by devoting half the proceeds to the CMS Hospital, the other half going to the All Saints’ Building Fund.

(These passages were excerpted from Irene Petrie, Missionary To Kashmir that was authored by Carus-Wilson and Mary Louisa Georgina Petrie and was published in 1901)