Centuries before the arrival of Shah-e-Hamadan and the rise of Sheikh Nooruddin Noorani in the fourteenth century, Kashmir knew about Islam and Muslims. Rajatarangini, Kashmir’s oldest poetic testament of ‘history’ offers enough details about Muslim living in Kashmir within less than 150 years after the prophet’s demise, writes Masood Hussain

Islam reached India within the lifetime of the prophet. The presence of the 15 x 40 ft Barwada Masjid in Gujarat’s ancient port town of Ghogha suggests that Islam reached India well before the prophet’s hijrat (migration) from Mecca to Madina. This dilapidated mosque almost faces the qibla-e-awal, the Jerusalem, a direction for prayers that changed towards Kabaa in 623 CE. Seemingly, the mosque was constructed within the first 13 years of Islam. By 700 CE, Muslims were ruling Sindh.

Interestingly, ancient Kashmir was also not as ignorant about Islam as it was earlier presumed. The presence of Muslims in Kashmir has been recorded less than 140 years after the demise of the prophet of Islam. Instead of Arab chroniclers, this information has been recorded by none other than Kalhana, Kashmir’s celebrated poet, who started writing about Kashmir’s kings and queens in 1148 CE. It took him almost two years to complete his Rajatarangini, the book that Kashmir showcases as the oldest written history of the region.

Kalhana, interestingly, avoided detailing the emergence of Islam in his chronicle – even though he lived in the times when a significant number of Muslims lived in Kashmir. His references to their presence are brief and linked to the local governance structure and its politics of it.

There were at least six Kashmir rulers in whose reigns Muslims existed. It is very difficult to determine if they were immigrants or natives. At one point in time the Muslims living in Kashmir periphery, mostly Dards, led a huge army into Kashmir. At another point in time, one of Kashmir’s kings sent a huge army against Mehmood Gaznavi in support of his ally in the Indian plains, mostly around current Punjab. It was well before the Gaznavi made two abortive attempts to get into Kashmir.

Vajriditya

(763-770)

Kalhana’s first mention of apparent Muslim presence in Kashmir is in the reign of Vajriditya, whom he terms a “cruel character” unlike his brother. The “wicked king” Kalhana makes us believe, was “a slave to avarice” and a “sensuous ruler” who had a large number of women in his seraglio – “with whom he diverted himself in turn, like a stallion with the mares”.

Kalhana has two major allegations against him. One, the king withdrew from Parihaspura temples “various foundations (granted) by his father”. Stein, who has worked on Rajatarangini, believes these could have been endowments sacerdotal apparatus and grants of the establishment. During the seven years of rule the “sinful king”, Kalhana (Book IV- 393-398) has recorded that “he sold many men to the Mlecchas and introduced into the country practices which befitted Mlecchas.”

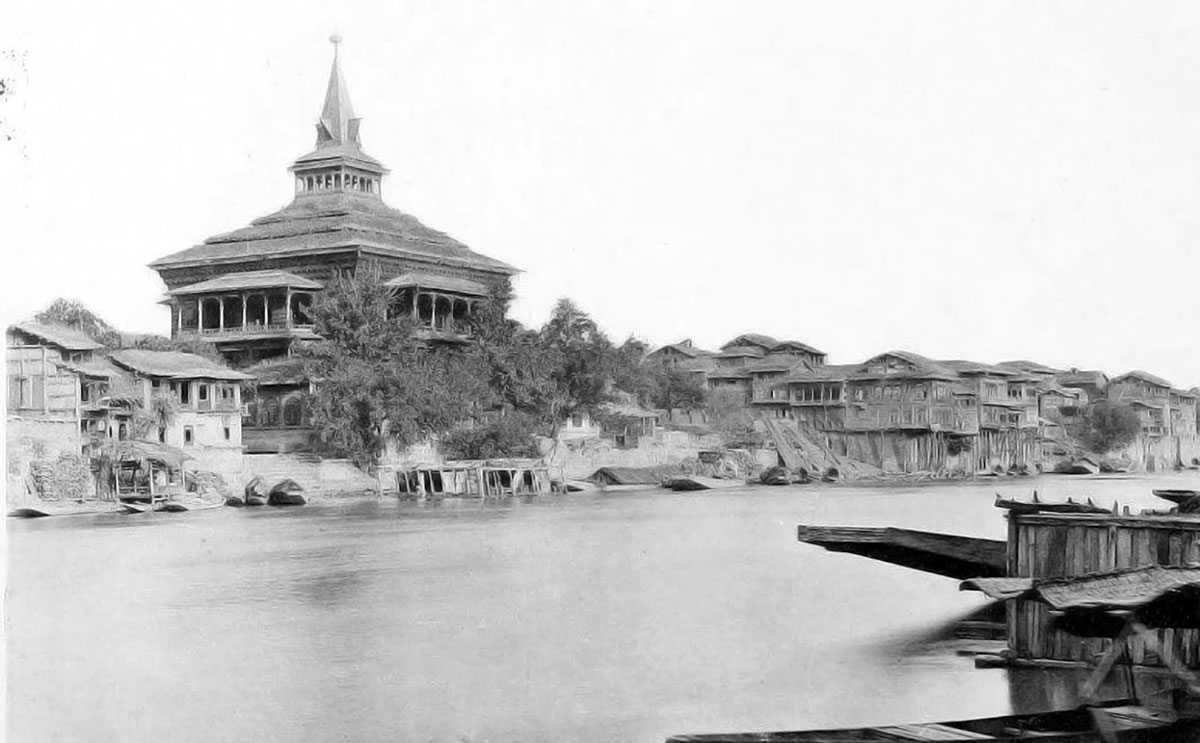

Mlecchas were Muslims and Srinagar’s Malchimar is apparently the first locality where Muslims lived in the history of Kashmir. Though the word Mlecchas refers to “outsiders” in the pre-Islamic period, historians see them as Muslims after the spread of Islam.

Samgramraja

(1003-1028)

The first-ever ruler from Lohara dynasty, Samgramaraja was an interesting ruler. His ascend to the throne was ensured by “fickle-minded” Kashmir queen Didha, who killed all the possible heirs to the throne one by one and eventually married a Poonch buffalo herder, Tunga, her Prime Minister and the chief of the army. After Didha’s death, when Samgramaraja took over, Tunga remained the most powerful.

Samgramaraja had allies. One of them was Sahi Trilocanapala, the son of Ananadpala, the last independent prince of the Hindu Shahiya clan whose dynasty was ruling a vast belt from Kabul Valley to Gandhara up to Western Punjab. It was one of the most disturbing eras in the plains as Mahmood Gaznavi was attacking this belt. Tense, the Gandhara ruler sought help from the Kashmir king and he sent a huge army under Tunga’s leadership.

The host king, according to Kalhana (book VII: 47-51) was surprised that Tunga’s army, otherwise “capable of making (the) earth shake” was operating strangely – neither having night watches, not posting scouts and avoiding exercises and planning attacks. Sahi told Tunga: “Until you have become acquainted with the Turuska warfare, you should post yourself on the scarp of this hill, (keeping) idle against your desire.” But a powerful Tunga was “intoxicated” with self-confidence. One day, he caught Gaznavi’s reconnaissance troops and killed them, which inflated his pride.

“In the morning then came in fury and in full battle array the leader of the Turuska army himself, skilled in stratagem. Thereupon the army of Tunga dispersed immediately,” Kalhana recorded. “Beaten like a jackal” the Rajatarangini recorded, Tunga “marched back slowly to his own country”. With the pride gone, sometime later, the weak king, killed Tunga along with his son, which undid a parallel power centre. This was the first major development in Kashmir, which was literally dictated by the Muslim actions on its borders.

Almost two years later, Gaznavi made two abortive attempts to enter Kashmir through Tosa Maidan pass but the weather saved Kashmir. However, he took a lot of areas around Kashmir; got residents converted and constructed mosques. Some of his troops later entered Kashmir as well.

Harsa

(1089-1101)

Rajatarangini has a mention of Kashmir king Ananta (1028-1063), who was fond of horses and had been hiring horse trainers, apparently Muslims. In his era, Kashmir played host to the surviving Sahi princes who had escaped Gaznavi forces.

However, most of the Muslim presence is seen in the era of Harsa (1089-1101), Ananta’s grandson, one of the interesting and enigmatic Kashmir rulers. Interestingly, Kalhana lived in the era and his father served Harsa.

Harsa started well, and was a huge lover of poets and knowledge seekers. “Formerly people in this country had, with the single exception of the king, worn their hair loose, had carried no headdress and no ear-ornaments,” Kalhana wrote, crediting Harsa for introducing “elegant fashions” – seen by Stein and others as the impact of Muslim presence around. “In this land where the commander-in-chief Madana, by dressing his hair in braids, and the prime minister Jayananda, by wearing a short coat of bright colour, had incurred the king’s displeasure, there this ruler introduced for general wear a dress which was fit for a king.”

At the same time, the ambitious Harsa was cruel. He created a situation that his father died a miserable death. He killed his younger brother to take over the throne. Kalhana accuses him of “numerous acts of incest”, which he committed with his own sisters and widows of his father. He was extravagant and that emptied the coffers. In order to extract money, he started attacking temples and seizing all metals.

“There was not one temple in a village, town or in the city which was not despoiled of its images by that Turuska, King Harsa,” Kalhana wrote. Turuska was another name given to Muslims and Rajatarangini scholars are still indecisive if at all, an “iconoclast” Harsa was doing this under the influence of Muslims. “While continually supporting the Turuska captains of hundreds with money, this perverse-minded king ate domesticated pigs until his death.”

Experts are sure that Harsa’s style changes in dress were dictated by Muslim influence and they insist he had a lot of Mlecchas serving his army in top positions.

Towards the end of his life, Harsa was extremely cruel with the rise of serious resistance from the growers, the Damras. He sent his army to massacre them. “He first attacked numerous Damarm of Holada in Madavarajya, and killed them just like birds in their nest,” Kalhana recorded about Harsa’s army’s actions around the Wullar lake. “While he was killing the Lavanyas (now Lone’s), he left in Madavarajaya not even a Brahman alive if he wore his hair dressed high and was of prominent appearance.” This terror led some of the Lavanyas to eat “cow meat in the lands of the Mlecchas”.

Bhiksacara

(1120-21)

The situation seemingly was changing quite fast in Kashmir as there were many claimants to the throne. Lohara king, Bhiksacara was weak and unable to manage the affairs of the country. His bete noire was Sussala. One day the king sent Bimba, his prime minister, with an army against Sussalu.

“Accompanied by Somapala, he drew to himself for assistance a force of Turuskas, the SallaraVismayahaving become an ally,” recorded Rajatarangini. Most scholars believe Sallara is an Arabic salar, the army chief. “Every single horseman among the Turuskascan said boastfully, showing a rope: “With this, I shall bind and drag along Sussala.” Who indeed would not have thought this coalition of Kashmiarin, Khasa and Mleccha forces capable of uprooting everything?”

What happened to the campaign is interesting. When Sussalu confronted the army, the soldiers deserted and joined him and eventually accompanied him to take over the throne in Kashmir! Experts believe that the Muslims who were allies of the Srinagar court were “of course, Muhaminadans from the Panjab or the lower hills.”

Jayasimha

(1128-49)

It was the worst of the civil war in Kashmir. While the Lohara dynasty members were fighting each other, the powerful peripheral feudal, the Damaras were holding sway.

“When Sanjapala went into camp with the Yavanas, the enemy became motionless, as trees keeping still in a calm,” Kalhana wrote. Yavanas is the other name that medieval Hindu writers have given to Muslims, in addition to Turuskas and Mlecchas.

This era was made interesting by the crisis that erupted after Dards lost their leader. A new succession battle emerged. As Jayasimha attempted to address it, it boomeranged and literally impacted his kingdom.

“Tile chiefs of the Mleecchas issued forth from the valleys adjoining Mount Himalaya from those which had witnessed the hidden indiscretions of the wife of wife of Kubera, and those were the cave-swellings resound with the songs of the city of the Kimnaras; from those to which knew of coolness on one side of the hot-sand ocean (valukambhodhi), and those which delight with their mountain breezes the Uttrakurus. Filing (all) regions with their horses they joined the camp of Darad-lord,” Kalhana recorded. Stein believes Uttarakrurus in the mythologic geography of the Indian Epos on the pattern of Hyperborean paradise. By valukambhodhi, he believes Kalhana means East Turkistan and Tibet.

Stein, however, makes two key observations. First, had Kalhana avoided the “mythical geography of the Himalaya regions”, we might have got the old names of “Astor, Gilgit, Skardo, and other regions on the upper Indus from which Viddasiha’s auxiliaries were in all probability drawn.” Second, if stress can be laid on the term Mleccha, “we should have to conclude that the conversion of the Dard tribes on the Indus from Buddhism to Islam had already made great progress in the twelfth century.”

The situation, however, triggers a serious conflict between Mlecchas from Dard areas and a Hindu Kashmir. It was a conspiracy between Bhoja and Kashmir king’s courtiers. The Dard army reached up to Wullar lake in 1140 summer.

“Subsequently he (Viddasiha) kept moving one march behind him, collecting the troops among which were numerous bands of Mlecchas. As the force which followed him, made the world tremble, Salhana’s son thought in his valour that he had the whole earth in his hands. Then the force strengthened by horsemen and the Mleccha chiefs, took its position at a place called Samudradhara, which put in terror (?),” Kalhana recorded of this conflict. “The proud Darda army then descended from the mountain gorges to battle with their horses, which carried golden trappings. The people feared that the territory invaded by the Turuskas had fallen [altogether] into their power, and thought that the whole country was overrun by the Mlecchas.”

However, they were attacked by a more powerful and formal army in Kashmir and defeated.

Early Influences

The reality remains that the Muslims in the early twelfth century were enough in number in Kashmir surroundings that they could mount a war in Kashmir. If it was the case then Kashmir’s transition to Islam must have started many centuries before Amir-e-Kabir and Nund Reshi, the two icons from the Muslim Sufi and Rishi orders, who are accredited for their contributions to the watershed shift in Kashmir’s faith and value system.

“Kashmir did not live in isolation. Trade was taking place throughout,” top historian and former Vice Chancellor of Allahabad University, Prof Rattan Lal Hangloo said. “Even Laltadatiya had Turks as allies and his harem had Turkish women. When Turks became Muslims, their relations with their allies did not change.”

Hangloo said Mlecchas was being used to describe all outsiders including Muslims unlike Turukas – still in vogue in parts of South India, which essentially meant Muslim. “The Turk Muslims brought in the idea of protection and sense of justice and that contributed to its spread,” Hangloo said.

Historian Prof Mohammad Ashraf Wani, whose The Making of Early Kashmir: Intercultural Networks and Identity Formation was published by Routledge in early 2023 said barring a brief period of Gaznavi invasion, Kashmir was never closed or inaccessible. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, he said, “we find the influx of people from erstwhile Śhahi kingdom, “foreign horse dealers,” dealers in “Turuśka girls, born in various distant regions,” artists from “Turuśka country,” employment of singers and dancers of “other lands,” induction of Brahmanas from Karnataka in the nobility of Kalasa, liberal patronage to talent “who had arrived from various countries” by Harśa and the existence of a colony of Saracens (Muslims) in the thirteenth century in Kashmir”. Kashmir, he asserted, “was not under any geographical siege; instead, the commercial, cultural and diplomatic relations with the neighbouring world continued unabated for a brief disruption during Mahmud’s invasion of north India.”