Ladakh is a perfect place to forget the banality of life to discover oneself altogether differently. Shams Irfan visited the land of Stupas recently where the marvels of nature bring solace from the ennui of life.

With a medley of excitement and anxiety that the prospect of visiting a new place brings with it, I left for Ladakh. This was my first journey into the land of mystic pleasures and deep meditations that attracts peace lovers from across the globe. I too decided to chase my destiny and let things unfold on their own rather than investigating them for the satisfaction of my journalistic ego.

Once you cross Sonmarg and ascend through the narrow mud and dirt track to the height of more than 11,000 feet at Zoji La, it feels like touching the skies. My driver, who would shift himself uneasily in his seat every time he negotiated a turn, was prying silently while we were crossing the mighty Zoji La. My photographer, who was accompanying me, was a dare-devil of sorts. He would fearlessly lean out of the window every time he saw something interesting to capture. The fact that Ladakh remains cut-off from rest of the world for almost three months added to our excitement. “It feels like travelling into a different world,” said my photographer on one occasion.

My first halt was at Drass, the second coldest place on earth where mercury drops to as low as minus 48 degrees Celsius in winters. Drass, a small town on the Srinagar – Kargil highway was unknown to the outside world and probably would have remained that way had the 1999 Kargil War not happened. “After the war, Drass became a must visit place for Indian tourists,” said Mohsin Raza, 28, a local shopkeeper.

After the war, Drass suddenly woke up to a huge rush of digital camera wielding tourists who would excitedly focus their lenses on the snow covered Tiger Hill seen in the distance. Most Indians who had seen Tiger Hill or Drass and Kargil only on their television screens feel overwhelmed on reaching the war torn town of Drass. “None of them would ever care to visit us and see how we are still paying for their victories,” rues Murtaza Ali, a resident of Drass.

You will find people making efforts in locating the exact hill among the vast range of snow covered peaks guarding Indian side of Kashmir. We stopped for lunch at Drass, when we saw a round-faced, curious looking man in his mid-forties, who had covered himself in layers of warm clothes, moving around anxiously with a cheap video camera slung across his neck. He finally approached our driver who had finished his lunch and was hanging around stretching his muscles after five hours of rough drive. “Yeh Tiger Hill kaunsa hai?” he asked with a heavy Bengali accented Hindi.

Our driver who has been to Ladakh on numerous occasions looked around with a puzzled expression on his face and finally pointed his fingers towards the highest visible peak in the distance, and said, ‘Woh Rahi (There it is)’. The man jumped in joy and quickly ran towards a bus parked in the distance and said something loudly in his native language. Within no time, around sixty awe-struck people of all ages and sizes alighted from a narrow exit door and started staring towards the snow covered peak pointed out by our driver.

They took out their cameras one by one and started taking photos of the famous hill. Thanks to Indian electronic media, the live images of Kargil War fill almost every single household in India replacing predictable and kitschy sop-operas. And for most Indians, Kargil War was all about recapturing a small but important Tiger Hill in some unknown world called Drass.

But after the war was over, tour operators grabbed the opportunity to cash in on the high emotions running among Indian middle class stirred by Hindi electronic media which portrayed Drass as a high victory ground. “It was only after Kargil War that Indian budget tourists started visiting Ladakh. Otherwise only foreigners would come here,” said Mohammad Raza, who exchanges foreign currency in main market of Drass.

Once we resumed our journey towards Kargil, I asked my driver whether the hill pointed out by him was the famous Tiger Hill. “I am not sure. They all look the same,” he replied casually. After two hours drive through listless villages, which are mostly guarded by military bases at entry and exit points, we reached Kargil. Kargil, a small district of about 1.5 lakh souls is located along the river Suru.

Divided by just 55 kilometres, Drass and Kargil remain cut-off from each during winters as the only access road is covered with snow.

Despite housing more than fifty percent of the entire Ladakh population, Kargil has remained relatively backward over the years as visitors often skip this town and visit Leh instead. During winters, when mercy touches minus 26 degrees celsius, everything in this town comes to a standstill. While passing though the main market, you get a feeling of being transported back in time. People wearing traditional attires move around lazily. Old women carry big stacks over their shoulders and it seems as if the entire air is filled with idleness of this town. Nobody is in a rush. Life moves at a slow pace here.

In contrast, Leh, which is located some 250 kilometres from Kargil, is buzzing with life during summers as the entire town is filled with foreigners. Kargil – Leh highway that runs along river Sindh passes through denuded mountains where no habitation can be seen for miles. Only living thing one sees while travelling to Leh is inside large military camps spread across the barren mountains. “There were hardly any troops visible along this highway before Kargil War. But now they are everywhere,” said Tashi Anchook, 42, an Aryan from Garkun Village, who walks 12 kilometres everyday to deliver mail in Batalik and other areas.

Interestingly, there are only a few fuel filling stations for vehicles in entire Ladakh. One is in Kargil while the next one is some 250 kilometres away in Leh. In between, there are just small villages, monasteries and vast waste land spread across miles. As one moves closer to Leh, small Stupas lining the side of the road guard small villages on both entry and exit points. Buddhists believe that these colourful Stupas of different sizes and shapes protect their villages from any evil or mischief. They are like protectors and are considered signs of prosperity. More the Stupas in a village, the better protected it is from evil forces.

After travelling for eight hours through vast and vacant mountain passes, we finally saw Leh town glowing under the clear summer sky in the distance. It was nearing midnight when we reached Leh. But the crowded roadside cafes, glowing signboards announcing easy currency exchange, uninterrupted internet connectivity and affordable hotels suggested that the town was abuzz with life.

During summers, Leh bustles with all sorts of activities; from refugee Tibetan markets to the now ruined seventeenth century Leh Palace, one could find backpack travellers everywhere. While walking around the main market in Leh, one cannot help but notice the extent of influence China has on this small northern most town of Kashmir. From cheap imitations of almost all international designer brands to swanky mobile phones and other electronic items, everything carries a Made in China tag.

But Leh could get boring after a few days if one does not move around. So I decided to brave sub zero temperature and tough road to explore the vast Nubra valley. The Nubra valley, 150 kilometres north of Leh, can be reached through Khardung La (world’s highest motorable road), only. Once you reach on top of Khardung La (18380 feet), the surrounding peaks shinning under the glowing morning sun look straight out of a miniature artist’s imagination.

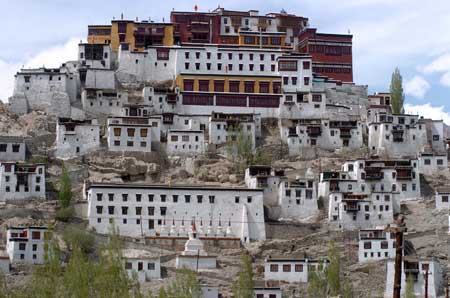

It took us around six hours to reach the serene Nubra Valley as one has to manoeuvre one of the most challenging roads on earth. Once we started to descend into the heart of Nubra Valley, we passed through several small villages where yaks were being used for tilling the ground for cultivation of Ladakh’s traditional staple diet, barley. Nubra valley is explorer’s heaven as it houses one of the biggest and oldest monasteries in Ladakh region called Diskit Monastery. Sitting on top of a hill and overlooking the merger of Shyok and Nubra River, Diskit Monastery offers panoramic view of the valley below.

After a long and tiring journey, I finally sat down to relax as the deafening silence of the Nubra Valley was too irresistible to neglect. Once back into the real world, we climbed down to the Diskit town for some Chinese delicacies. On our way back from Diskit, our driver made an unplanned stopover at a small dusty village called Hunder. The stopover soon turned out to be the best part of our journey as my photographer almost jumped out of the moving vehicle at sight of the double hump camels.

Our driver informed us that Hunder village is divided into two parts; one part is cold desert where these double hump camels survive and the other part is among a few fertile areas in entire Nubra Valley. The thirty household strong small population of Hunder is outnumbered by a large military hutment area that occupies almost entire eastern side of the village. On our way back to Kashmir valley, I and my photographer both sat silent, lost in our own thoughts, perhaps saving our memories of the place in our own fashion.

“Ladakh is the perfect place to get lost and to find oneself altogether differently,” said Klauss, a German tourist who I met at Diskit monastery.